The 1970s delivered some of the most memorable ads ever made, but many would not pass today’s standards. Cultural norms, health regulations, and stricter advertising rules have changed what brands can say and how they say it.

Looking back shows how ideas about gender, health, and representation evolved, sometimes dramatically. Here are 10 notable examples and why they would not make it on air now.

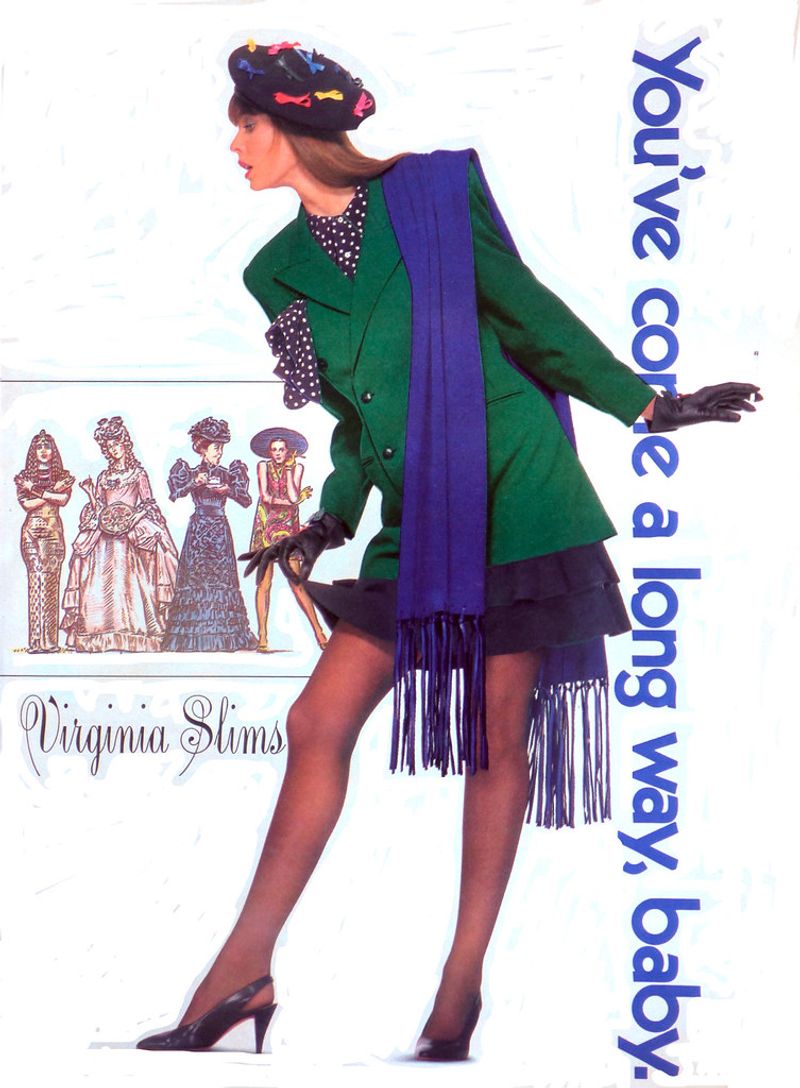

1. Virginia Slims – ‘You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby’

Virginia Slims built an identity around women’s liberation, selling cigarettes with the line “You’ve come a long way, baby.” The visuals often featured chic models in tailored outfits, emphasizing independence, workplace ambition, and social freedom. The message paired empowerment with smoking, suggesting progress could be held in a slim white cigarette.

Today, this would not air for two major reasons. First, tobacco advertising is restricted or banned on broadcast in many markets, especially in the U.S., where TV and radio tobacco ads have been off the air since 1971.

Second, linking empowerment to nicotine would be criticized as manipulative health messaging.

Health authorities and advocacy groups have documented the harms of smoking, and regulators require warnings and strict placement rules. The conflation of feminism with a product known to cause disease now reads as cynical at best.

You can still find these ads in archives, but their tone clashes with current public health norms. Modern campaigns aiming at women avoid glamorizing addictive products.

This example shows how ad culture once framed social change as a sales tactic.

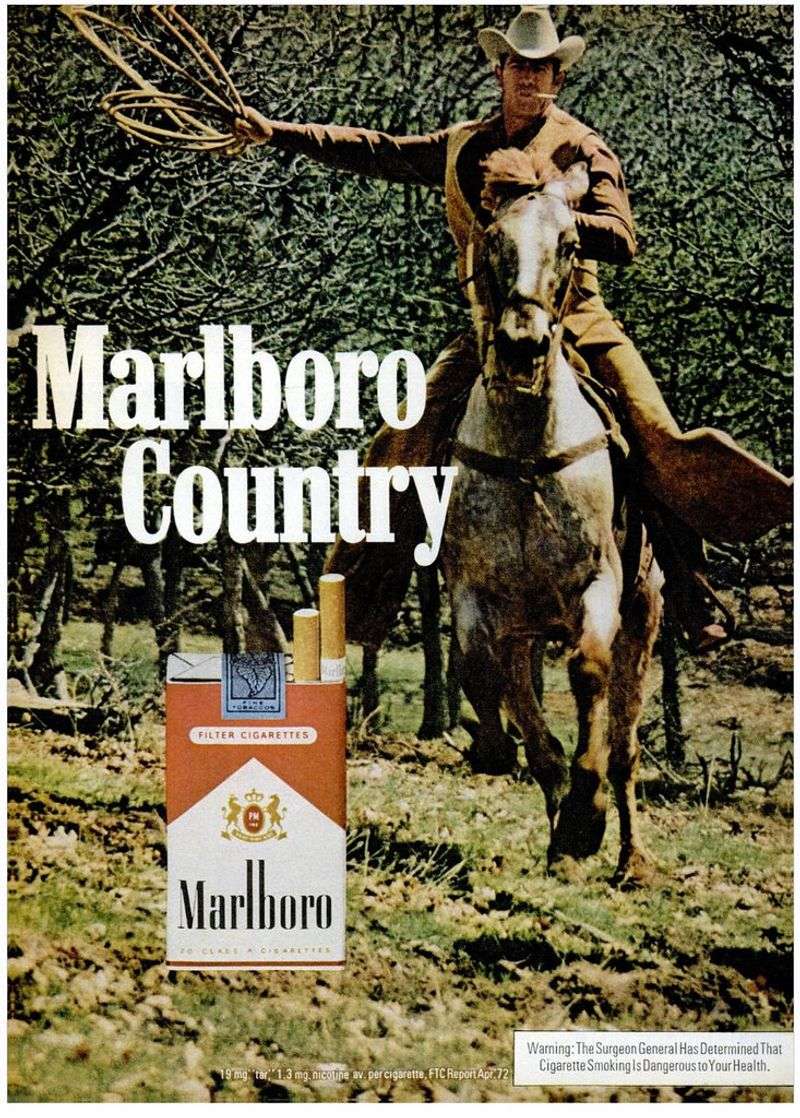

2. Marlboro – Cowboy lifestyle cigarette ads

The Marlboro Man dominated 1970s cigarette advertising with sweeping Western vistas and rugged cowboy imagery. The message was simple and powerful: masculinity, independence, and clarity were found under a wide sky with a Marlboro in hand.

These spots were cinematic, aspirational, and very effective at normalizing daily smoking.

Today, such TV ads are illegal in the U.S. due to long standing restrictions on broadcast tobacco marketing. Beyond regulation, the cultural climate has shifted.

Narratives that equate rugged identity with smoking face criticism for glamorizing addiction.

Public health evidence linking smoking to cancer and heart disease is now central in media literacy. Anti tobacco groups and regulators require strong warnings and restrict youth appealing imagery.

A cowboy icon would be read as an attempt to bypass health concerns through myth. As a result, Marlboro’s brand presence has moved to adult only channels with strict rules.

While the imagery remains a case study in branding, it would not pass current standards.

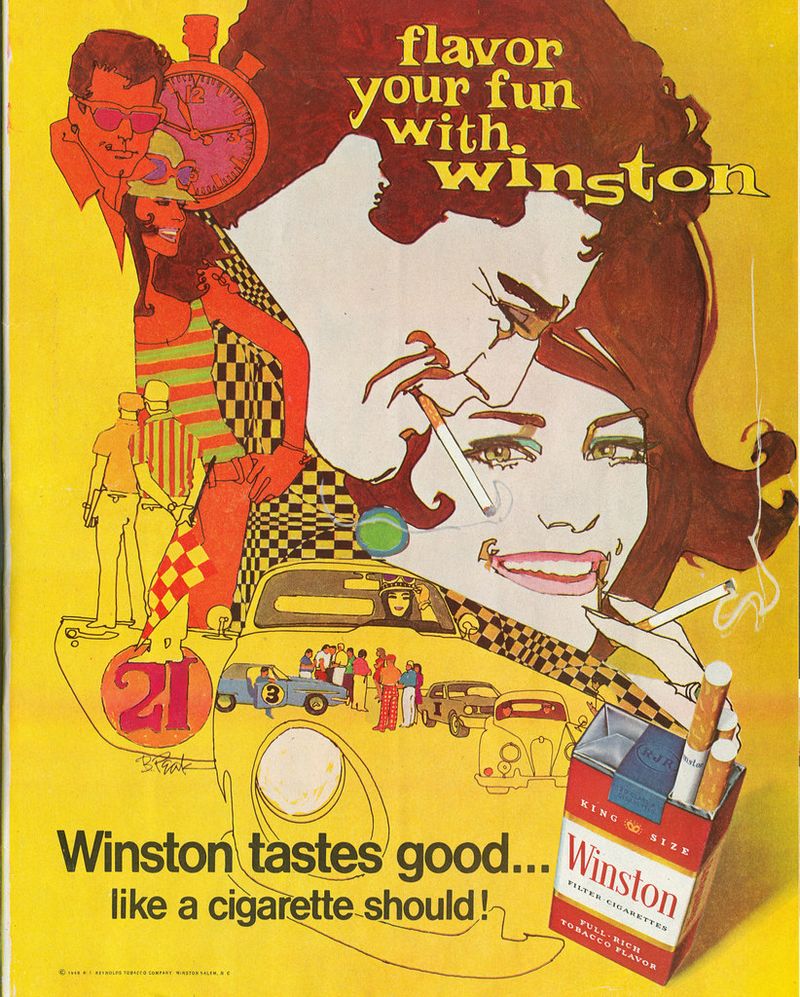

3. Winston – ‘Winston tastes good like a cigarette should’

Winston’s jingle “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should” embedded smoking into everyday routines with catchy repetition. The framing made cigarettes appear normal, even wholesome, as if taste and habit were the only considerations.

Ads often showed relaxed social scenes, humor, and easy conversation.

Contemporary standards would not allow this framing on broadcast TV or radio in the U.S. Regulations aside, audiences expect responsible depictions of health risks.

Portraying cigarettes as a simple pleasure invites accusations of glamorization and minimization of harm.

Modern advertising policies and platform rules typically require robust age gating and avoid positive lifestyle associations with tobacco. Health authorities emphasize addiction and long term risks, not taste or fun.

A straight “tastes good” message clashes with guidance on reducing youth appeal and misleading impressions. While the jingle endures in advertising history, its premise no longer aligns with current practice.

Brands today are held to clearer standards on claims, disclosures, and context, especially when products carry significant public health consequences.

4. Alka-Seltzer – “I can’t believe I ate the whole thing”

The Alka-Seltzer line “I can’t believe I ate the whole thing” turned overindulgence into a punchline. The ad leaned on a relatable scenario, then offered quick relief.

It captured the sitcom rhythm of the era, where food excess and a fizzy fix were played for gentle laughs.

Modern health communication tends to be more careful about normalizing overeating and quick pharmaceutical answers. Regulations on claims, disclosures, and comparative effectiveness are tighter, and brands balance humor with clearer guidance.

You are more likely to see portion awareness and responsible use language today.

While not offensive, the spot feels dated in tone and framing. It positions discomfort as an expected outcome and medication as a routine counterbalance.

Contemporary ads often pair symptom relief with lifestyle context and safety notes. The original still stands as a classic in copywriting and catchphrases, but the cultural cue has shifted.

Viewers expect nuance when health intersects with humor, and that is why the same joke would likely land differently now.

5. Burger King – “Have it your way”

Some 1970s Burger King ads paired customization with jokes that leaned on men ordering and women serving. The humor used gendered cues that, even subtly, signaled who was in charge.

In the moment, it read as everyday banter. Now it scans as dated and dismissive.

Modern quick service ads still use humor but are careful about who delivers it, and at whose expense. Brands have learned that role based jokes can alienate customers and invite criticism.

Corporate standards and agency DEI reviews screen for bias more actively.

“Have it your way” remains a strong brand line, yet its older executions feel misaligned with current values. Audiences expect inclusive casting, respectful interactions, and light humor that does not punch down.

A throwaway joke about service roles would get clipped, reposted, and critiqued within hours. That feedback loop changes creative choices long before production.

You can still appreciate the jingle, but the framing would not pass today.

6. Old Spice – “The mark of a man”

Old Spice ads in the 1970s positioned scent as proof of manhood, often implying women were rewards for the right grooming choice. The copy equated stoicism and dominance with desirability.

It fit a broader cultural script of narrow masculinity.

Today, campaigns that define “real men” narrowly face pushback for reinforcing restrictive norms. Audiences expect brands to reflect a range of identities and to avoid objectifying anyone.

The idea that purchase equals entitlement to attention reads as transactional and dated.

Old Spice has since reinvented itself with parody and self aware humor, sidestepping rigid tropes. That pivot illustrates the lesson many brands learned: tone and inclusivity matter as much as memorability.

A direct “mark of a man” message would be labeled toxic and risk platform restriction. Modern grooming ads tend to highlight confidence, self expression, and playfulness rather than conquest.

The shift shows how quickly meaning changes when culture does.

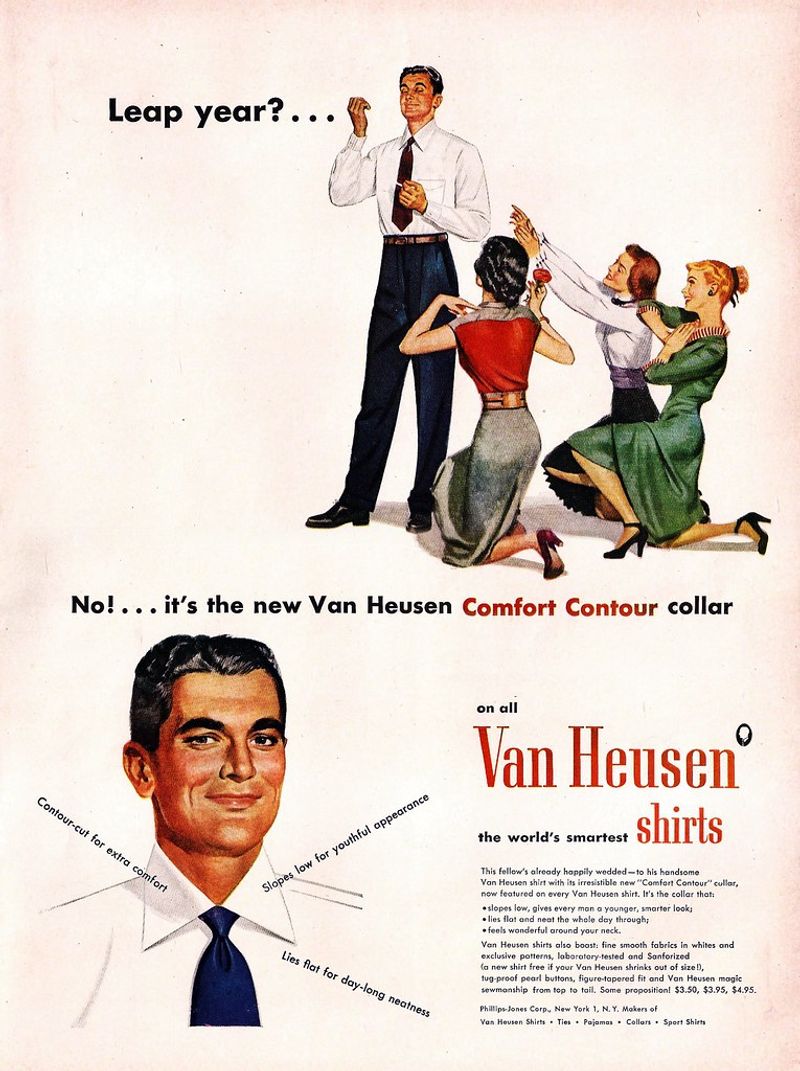

7. Van Heusen – “Look what happened to me!”

Van Heusen ran print ads under the line “Look what happened to me!” showing aggressive physical grabs or domineering poses. The creative framed boundary pushing as cheeky fun, using shock to sell shirts and ties.

It is one of the era’s most cited examples of using sexual dominance as humor.

Contemporary standards around consent and representation are far stricter. Imagery that looks like harassment or assault would be unacceptable to publications and platforms.

Retailers would likely refuse placement, and social media would drive rapid backlash.

Advertisers now prioritize clear, respectful dynamics and consider how scenes might be read across audiences. Even suggestive choreography is vetted for tone and context.

The Van Heusen approach treats discomfort as a punchline, which no longer flies. It stands as a reminder that provocation without care can date a brand quickly.

In review, it is a case study in what not to revive from archive mood boards.

8. Pepsi / Coke ads with stereotypical “ethnic” portrayals

Some 1970s soda ads used caricatured accents, token casting, or simplified cultural scenes to suggest global appeal. The intent was inclusion, but execution leaned on stereotypes.

Visual shortcuts replaced authentic representation, creating a dated, flattening effect.

Today, brands invest in cultural consultants, inclusive casting, and specific storytelling to avoid this. Audiences quickly call out accents and tropes that feel performative or mocking.

Major companies have issued apologies for ads that miss the mark.

Regulators may not ban every instance, but platform and public standards apply real pressure. The expectation is to show people as people, not as costume notes.

When in doubt, teams test messages with communities represented. The 1970s approach reveals how “worldly” could slip into tokenism.

Modern soda campaigns tend to focus on shared moments without leaning on reductive shorthand. That shift reflects both ethics and smart brand protection.

9. Jell-O / Kool-Aid ads with kids eating sugar nonstop

In the 1970s, kid focused ads often celebrated endless sugary snacks and drinks as everyday fuel. Bright colors, big smiles, and animated mascots made excess look normal.

Parents in the background nodded along as bowls and pitchers kept refilling.

Today, while treats still advertise widely, messaging is more careful. You will see portion cues, balanced meal language, and occasional nutrient fortification notes.

Regulations and platform guidelines discourage implying that sugar heavy foods are staples without context.

Public health campaigns about childhood nutrition have changed expectations. Brands try to avoid appearing indifferent to wellness, especially with kids onscreen.

Mascots remain, but with toned down claims and more active play framing. The older nonstop serving visuals would read as irresponsible.

You can still find nostalgia in the jingles, but the presentation would be reworked to meet current norms. Responsible creative now aims for fun without endorsing unchecked intake.

10. Candy Cigarettes ads

Candy cigarettes were marketed with packaging that mirrored real cigarette brands, right down to colors and logos. Ads and displays made them feel like a playful rite of passage.

Kids could mimic adult behavior with a sweet stand in.

Today, many regions restrict or discourage sales and advertising because of concerns about normalization. Public health groups have described the product as a potential gateway that trivializes smoking.

Retailers often keep them off shelves to avoid controversy.

Even where legal, you rarely see overt promotion. Platforms also apply strict rules to anything resembling tobacco targeting minors.

The visual mimicry that once created novelty now reads as inappropriate. As with real tobacco, glamor cues are avoided in kid facing media.

The product’s nostalgia competes with evidence based caution, and policy leans toward the latter. That is why these ads would not make it to air now.