Standing before structures built thousands of years before recorded history can make you feel incredibly small yet deeply connected to humanity’s shared past. Around the globe, remarkable ancient sites still welcome curious travelers who want to walk where our earliest ancestors worshiped, built communities, and shaped civilizations.

From prehistoric temples older than the pyramids to fortresses that have witnessed empires rise and fall, these twelve destinations offer more than just history lessons—they provide tangible links to the ingenuity and spirit of people who lived millennia ago. Pack your sense of wonder and prepare to step back in time.

Göbekli Tepe — Turkey (c. 9600 BCE)

Carved stone pillars rise from the earth like ancient sentinels guarding secrets from a time before farming, before cities, before almost everything we consider civilization. Göbekli Tepe shatters every assumption about when humans first organized to build monumental structures.

Over 11,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers somehow coordinated to quarry, transport, and erect massive T-shaped limestone blocks weighing up to 16 tons each.

The site features at least twenty circular enclosures, though only a fraction have been excavated so far. Intricate carvings of foxes, lions, scorpions, and vultures decorate many pillars, hinting at belief systems we can barely imagine.

No evidence of permanent habitation exists here—people traveled to this hilltop specifically for rituals or gatherings.

Modern visitors walk elevated pathways that protect the fragile ruins while offering stunning views of these prehistoric rings. A well-designed visitor center provides context through exhibits and reconstructions.

Standing among these ancient stones, you realize this wasn’t just a temple—it represents humanity’s first architectural ambition, built when our ancestors were supposedly too primitive for such undertakings.

Tower of Jericho — West Bank (c. 8000 BC)

Climbing the internal staircase of this 10,000-year-old tower feels like descending into humanity’s architectural memory. The Tower of Jericho stands as one of the earliest examples of monumental construction, predating metalworking and the wheel.

Built from undressed stones, this cylindrical structure reaches about 8.5 meters high with walls over a meter thick.

Archaeologists debate its original purpose—was it defensive, ceremonial, or something else entirely? What’s certain is that building it required organized labor and planning on a scale previously unknown.

The tower forms part of ancient Jericho’s fortifications, making this potentially the world’s oldest walled city.

Tell es-Sultan, the archaeological mound containing the tower, reveals layer upon layer of human occupation stretching back millennia. Visitors can explore the excavated areas, walking among stone foundations of ancient dwellings and defensive walls.

The site offers a tangible connection to the moment when humans transitioned from nomadic life to settled communities.

Despite its age, the tower’s engineering remains impressive—its stones fit together without mortar, held by weight and careful placement. Standing beside it, you’re touching stones shaped by hands that knew nothing of later civilizations.

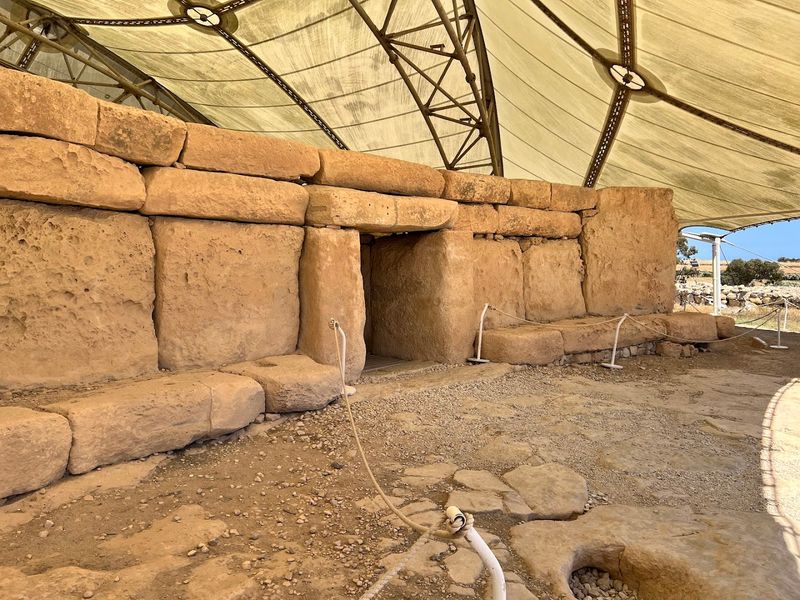

Megalithic Temples of Malta — Malta (c. 3600–2500 BC)

Limestone blocks weighing several tons each form doorways, altars, and chambers that predate Egypt’s pyramids by centuries. Malta’s megalithic temples represent humanity’s earliest freestanding stone architecture dedicated to worship.

Between 3600 and 2500 BC, prehistoric islanders quarried, transported, and precisely positioned these enormous stones without metal tools or wheels.

Ġgantija on Gozo island translates to “giant’s tower” because locals once believed only giants could have built such structures. The temples feature sophisticated architectural elements including corbelled roofing techniques and carved decorations. Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra on Malta’s southern coast align with solstices, revealing astronomical knowledge.

Walking through these ancient sanctuaries, you notice the careful planning—forecourts leading to inner chambers, altar stones positioned for rituals, and decorative elements suggesting complex belief systems. UNESCO recognition protects these remarkable sites, though weather and time have taken their toll on the soft limestone.

Visitor centers at major temple sites provide context through artifacts and reconstructions. Standing within these 5,000-year-old walls, you’re surrounded by evidence of a sophisticated temple-building culture that flourished and vanished, leaving behind only these magnificent stone witnesses.

Stonehenge — England (c. 3000–2000 BC)

Those massive sarsen stones silhouetted against English skies have captivated imaginations for millennia, and seeing them in person never disappoints. Stonehenge’s iconic stone circle represents over a thousand years of construction and modification beginning around 3000 BC.

The monument’s builders transported bluestones from Wales—over 150 miles away—demonstrating remarkable determination and organizational capability.

The largest sarsen stones weigh around 25 tons each, carefully shaped and erected to support horizontal lintels in a perfect circle. Precise astronomical alignments suggest the monument tracked solar and lunar cycles, possibly for agricultural or ceremonial purposes.

Theories about Stonehenge’s function range from healing temple to astronomical observatory to ancestral burial ground.

Modern visitors view the stones from a designated path that protects the fragile monument while allowing close observation. The visitor center features reconstructed Neolithic houses and displays explaining construction techniques and cultural context.

Special access visits allow entry inside the stone circle during sunrise or sunset.

Despite centuries of study, Stonehenge guards many secrets. How exactly did Bronze Age people move and erect these enormous stones?

What rituals occurred here? Standing before these ancient monoliths, you’re confronting mysteries that may never be fully solved.

Great Pyramids of Giza — Egypt (c. 2560 BC)

Nothing quite prepares you for the sheer scale of these ancient tombs rising from the desert sand. The Great Pyramid of Khufu, built around 2560 BC, originally stood 481 feet tall and remained the world’s tallest human-made structure for nearly 4,000 years.

Approximately 2.3 million stone blocks, each weighing several tons, form this architectural marvel.

Construction required extraordinary engineering knowledge—the pyramid’s base is nearly perfectly level, and its sides align almost exactly with cardinal directions. Workers quarried, transported, and precisely positioned these massive stones without modern machinery, creating smooth angled faces that once gleamed with white limestone casing.

The Giza complex includes three main pyramids, the enigmatic Sphinx, and several smaller subsidiary pyramids. Visitors can enter the Great Pyramid’s cramped passageways leading to internal chambers, though claustrophobia-inducing conditions aren’t for everyone.

The site’s new Grand Egyptian Museum provides comprehensive context about pyramid construction and ancient Egyptian civilization.

Crowds and commercialization surround the pyramids today, but their monumental presence still inspires awe. These aren’t just tombs—they’re statements of pharaonic power, mathematical precision, and a civilization’s determination to achieve immortality through stone.

Standing at their base, you understand why they’ve fascinated humanity for millennia.

Amman Citadel — Jordan (Bronze Age onward)

Perched on Amman’s highest hill, this archaeological treasure reveals thousands of years of continuous human occupation in stunning layers. The citadel’s earliest remains date to the Bronze Age, around 1800 BC, though the site likely saw activity even earlier.

Civilizations from Ammonites to Romans to Umayyads left their marks here, creating a vertical timeline of Middle Eastern history.

The Temple of Hercules dominates the site with its towering columns, built during Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius’s reign. Nearby, Byzantine churches show Christian influence, while the Umayyad Palace complex represents Islamic architectural achievement from the 8th century.

A massive stone hand fragment from a Hercules statue hints at the temple’s original grandeur.

Walking these ancient pathways offers panoramic views of modern Amman sprawling below—a striking contrast between past and present. The Jordan Archaeological Museum on-site displays artifacts spanning millennia, including some of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Excavations continue revealing new discoveries about the citadel’s complex history.

What makes this site special is its layered narrative. You’re not visiting one civilization’s ruins but experiencing how successive cultures built upon, modified, and honored what came before.

The citadel represents continuity, showing how humans have valued this strategic hilltop for over three thousand years.

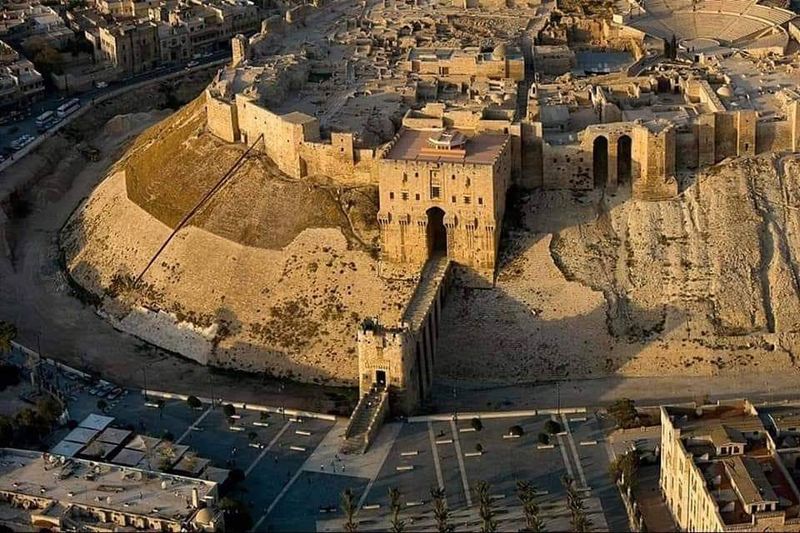

Citadel of Aleppo — Syria (3rd millennium BC origins)

Rising dramatically from Aleppo’s ancient heart, this fortress tells stories of conquest, survival, and resilience spanning five millennia. The citadel’s strategic hill saw human activity from at least the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, making it among the world’s oldest continuously used fortifications.

Hittites, Assyrians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Crusaders, Mamluks, and Ottomans all recognized this site’s military importance.

The massive entrance bridge and gate, built during the Mamluk period, create an imposing approach to the fortress. Inside, visitors find a complex city-within-a-city featuring palaces, mosques, barracks, and underground passages.

The Great Mosque within the citadel dates to the 12th century, while deeper excavations reveal much older structures.

Recent conflict severely damaged portions of the citadel, but restoration efforts have reopened many areas to visitors. The site’s survival through countless wars and sieges speaks to both its strategic value and robust construction.

Walking its ancient stones connects you to every army that ever marched through this crossroads of civilizations.

From the citadel’s heights, Aleppo’s old city spreads below—itself one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited urban centers. This fortress isn’t just a military structure; it’s a monument to human persistence and the enduring importance of this ancient trading hub.

Newgrange — Ireland (c. 3200 BC)

Every winter solstice, sunlight penetrates this ancient tomb’s narrow passage, illuminating the inner chamber for exactly seventeen minutes. Newgrange predates both Stonehenge and Egypt’s pyramids, built around 3200 BC by Neolithic farmers who understood astronomy with remarkable precision.

The monument’s construction required transporting hundreds of thousands of tons of stone and creating a structure that remains watertight after 5,000 years.

The tomb’s facade features brilliant white quartz stones that would have gleamed spectacularly when new. Massive kerbstones surround the circular mound, many carved with spirals, lozenges, and other enigmatic symbols.

The entrance stone’s intricate triple spiral design has become an iconic symbol of ancient Ireland.

Inside, a 19-meter passage leads to a cruciform chamber with a corbelled roof that has never leaked—a testament to Neolithic engineering. The winter solstice alignment wasn’t accidental; builders designed a roof-box specifically to channel sunrise light deep into the tomb.

UNESCO recognizes Newgrange as part of the Brú na Bóinne complex, which includes other significant prehistoric monuments.

Visiting requires booking through the interpretive center, which provides excellent context about Neolithic life and beliefs. Standing within this ancient chamber, you’re experiencing a 5,000-year-old light show that connects past and present through the eternal rhythm of celestial movements.

Skara Brae — Scotland (c. 3180 BC)

Storm winds in 1850 stripped away sand dunes to reveal something extraordinary—an intact Neolithic village frozen in time. Skara Brae on Scotland’s Orkney Islands dates to approximately 3180 BC and offers an unparalleled glimpse into daily life over 5,000 years ago.

Unlike monumental temples or tombs, this site shows how ordinary prehistoric people actually lived, worked, and organized their community.

Eight remarkably preserved stone houses cluster together, connected by covered passageways. Inside each dwelling, you see stone furniture still in place—box beds, dressers, storage boxes, and central hearths.

The builders used flat stone slabs ingeniously, creating surprisingly comfortable living spaces. Even a primitive drainage system shows sophisticated planning.

Preservation is exceptional because everything was built from stone—Orkney’s treeless landscape forced inhabitants to work with available materials. When the village was abandoned around 2500 BC, windblown sand buried and protected it until that fateful 1850 storm.

Today, visitors walk elevated paths around the houses, peering into these ancient homes.

What makes Skara Brae special is its humanity. These weren’t gods or kings but families who cooked meals, made tools, and raised children in these very rooms.

Standing here, the Neolithic period stops being abstract history and becomes tangibly, movingly real.

Çatalhöyük — Turkey (c. 7500 BC)

Imagine a town where homes had no doors, and residents entered through roof openings using ladders. Çatalhöyük, occupied from approximately 7500 BC, represents one of humanity’s earliest experiments with urban living. This Neolithic settlement housed up to 8,000 people at its peak, with houses built so tightly together that residents walked across rooftops to navigate the town.

The site reveals sophisticated social organization emerging thousands of years before what we typically consider civilization. Houses feature elaborate wall paintings and plaster reliefs depicting bulls, leopards, and human figures.

Residents buried their dead beneath sleeping platforms, keeping ancestors literally underfoot. Evidence shows they domesticated plants and animals while maintaining hunting traditions.

Excavations continue revealing new insights about Neolithic life. The site’s preservation is remarkable—layers of occupation show how houses were periodically demolished and rebuilt on the same spot, creating a tell (artificial mound) that preserves thousands of years of habitation.

UNESCO World Heritage status protects this invaluable archaeological treasure.

Visitors can tour excavation areas and a modern museum displaying artifacts and explaining the site’s significance. While less visually dramatic than stone temples, Çatalhöyük offers something profound—evidence of humans learning to live together in large communities, navigating social complexities, and creating culture that would eventually lead to cities and civilizations.

Jerusalem Old City — Continuous History (ancient layers)

Few places on Earth compress so much human history into such a small space. Jerusalem’s Old City isn’t a single ancient structure but a living archaeological layer cake where Bronze Age walls support medieval buildings, Roman stones form Byzantine churches, and Crusader fortifications protect Islamic shrines.

Continuous occupation for thousands of years created a unique urban palimpsest where past and present interweave inseparably.

The Western Wall, a retaining wall from Herod’s Second Temple expansion around 19 BC, remains Judaism’s holiest site. Nearby, the City of David excavations reveal walls and water systems from over 3,000 years ago.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre sits atop layers of Roman and Byzantine construction, while the Dome of the Rock rises from the ancient Temple Mount.

Walking Old City streets means traversing history—your feet touch stones worn smooth by countless pilgrims across millennia. Archaeological excavations constantly reveal new layers, from Canaanite fortifications to Hasmonean palaces to Roman colonnades.

Four quarters—Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and Armenian—each preserve distinct cultural heritage while sharing ancient walls.

What makes Jerusalem extraordinary is its continued vitality. This isn’t a preserved archaeological park but a living city where ancient stones support modern life, where history isn’t past but present, and where three major religions maintain active holy sites within less than one square kilometer.

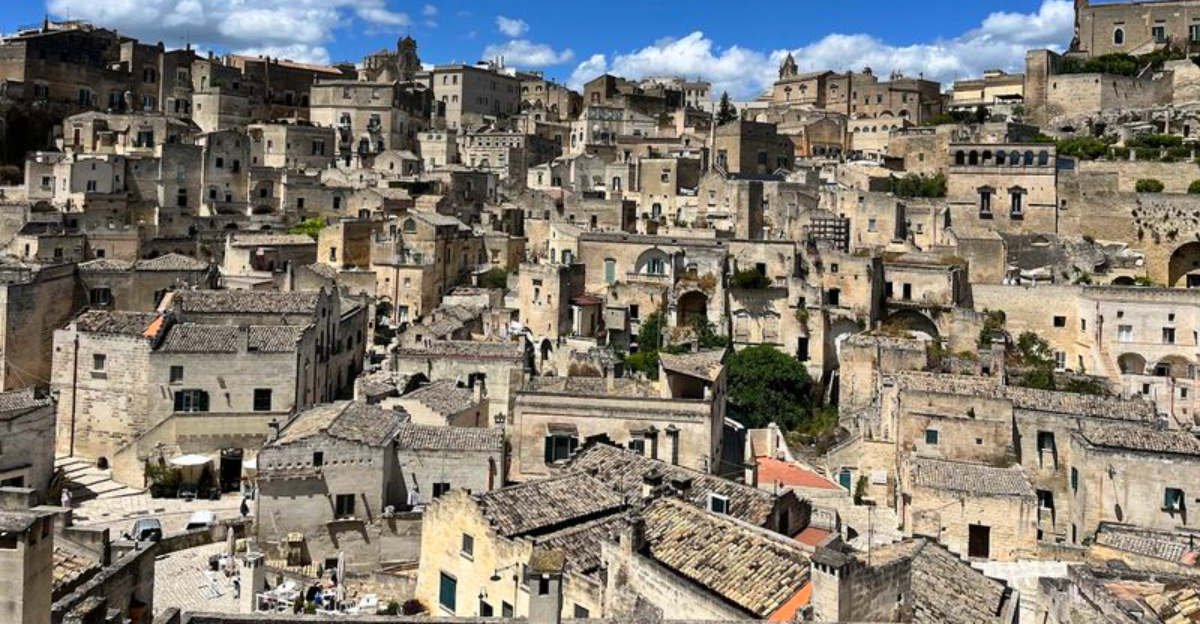

Matera’s Sassi — Italy (ancient cave dwellings)

Carved directly into limestone cliffs, these ancient cave dwellings create one of the world’s most extraordinary urban landscapes. Matera’s Sassi districts—Sasso Caveoso and Sasso Barranco—contain dwellings continuously inhabited for millennia, with archaeological evidence reaching back to Paleolithic times.

The caves evolved over centuries from simple shelters to complex multi-level homes, churches, and community spaces.

What began as natural caves expanded through human ingenuity into a sophisticated troglodyte city. Residents carved rooms, cisterns, and ventilation systems into soft stone, creating comfortable living spaces naturally insulated against summer heat and winter cold.

Churches excavated from solid rock feature frescoes and architectural details rivaling surface buildings. The city’s ingenious water management system collected and distributed rainfall through carved channels and cisterns.

By the 1950s, poverty and poor sanitation led to the Sassi’s evacuation, but recent decades brought remarkable restoration. Today, cave dwellings house hotels, restaurants, museums, and residences, earning UNESCO World Heritage status.

Visitors explore labyrinthine streets and staircases connecting different levels of this vertical city.

Matera demonstrates how humans adapt to landscape rather than dominating it. These aren’t primitive caves but sophisticated architecture that works with natural stone.

Walking these ancient passages, you experience a unique urban form where buildings and bedrock merge, where homes carved by ancient hands still shelter modern residents.