History textbooks often skip the most fascinating stories. While we learn about a handful of famous figures, countless Black changemakers who reshaped America never made it into our classrooms.

These 13 individuals challenged injustice, broke barriers, and transformed society in ways that still echo today, yet their names remain largely unknown outside academic circles.

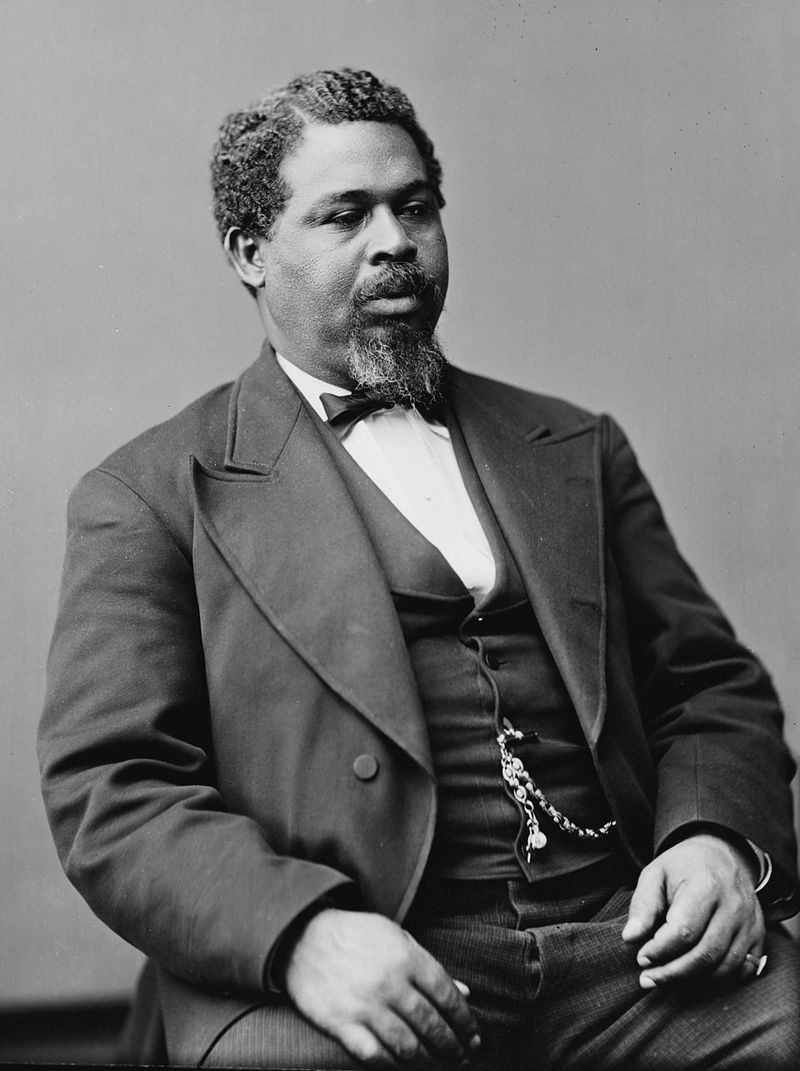

Robert Smalls

Stealing a Confederate warship right under enemy noses is exactly what Robert Smalls pulled off in 1862, steering the Planter out of Charleston Harbor while wearing the captain’s hat to fool Confederate checkpoints. He had memorized the secret signals and navigated past five fortifications before reaching Union ships at dawn.

Smalls didn’t stop there. He used his newfound freedom to become a force in Reconstruction politics, serving five terms in Congress.

During his time in the South Carolina legislature, he helped establish the state’s first free public school system, a radical idea at the time.

What makes his story remarkable is how he transformed from enslaved pilot to political powerhouse in just a few years. He fought to protect Black voting rights and pushed for education reforms that benefited everyone.

His military knowledge proved invaluable to Union forces, and he even purchased his former enslaver’s house after the war.

Smalls lived until 1915, long enough to see some of his achievements rolled back during Jim Crow. Still, his audacious escape and political courage set a standard for what one determined person could accomplish against impossible odds.

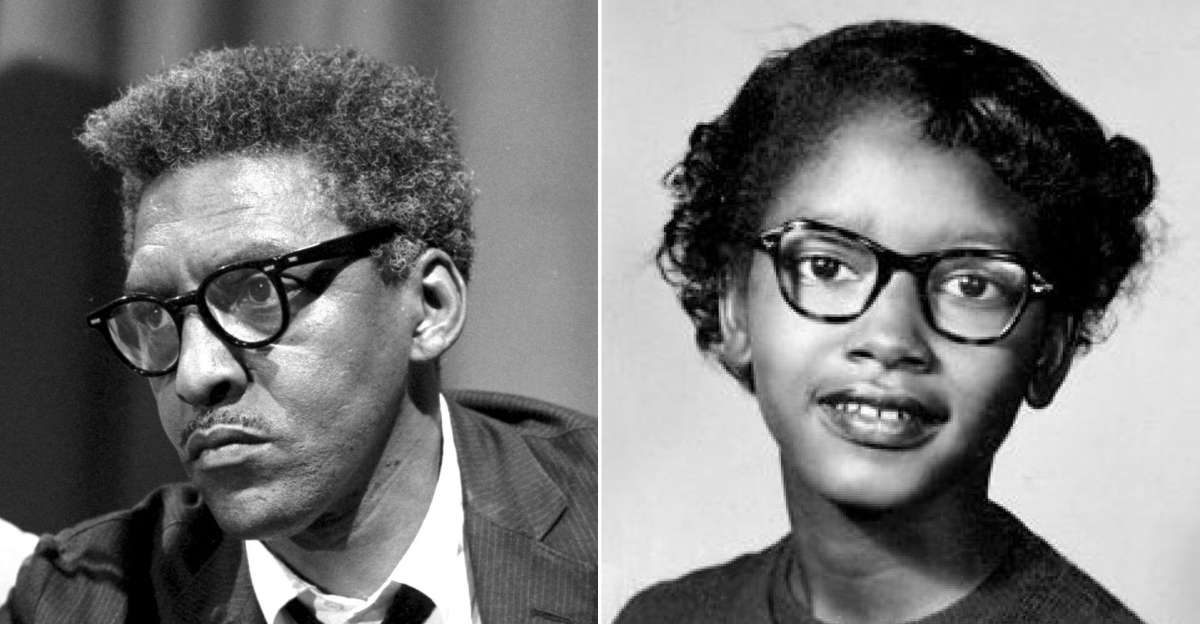

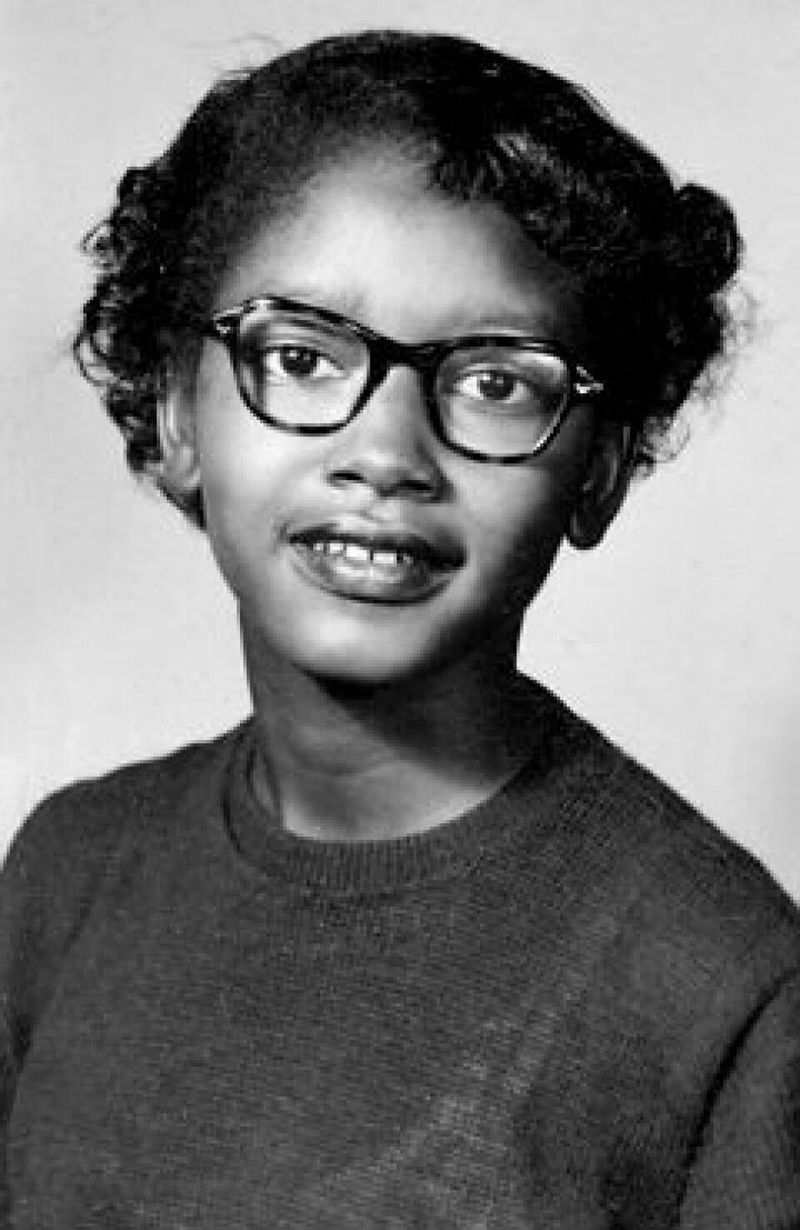

Claudette Colvin

Nine months before Rosa Parks became famous, a 15-year-old student made the same stand. Claudette Colvin refused to surrender her bus seat on March 2, 1955, and police dragged her off in handcuffs.

She later said the spirits of Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth pushed down on her shoulders, making it impossible to move.

Civil rights leaders initially planned to rally around Colvin’s case. However, they decided a pregnant teenager wouldn’t be the ideal face for their carefully orchestrated campaign.

The decision stung, but Colvin didn’t back down when it mattered most.

She became a key plaintiff in Browder v. Gayle, the federal case that actually ended bus segregation in Montgomery.

While Parks’ arrest sparked the famous boycott, Colvin’s legal testimony helped win the constitutional battle. Her courage in court, facing hostile lawyers and a skeptical judge, proved essential to victory.

For decades, her contribution went largely unrecognized. Only recently have historians and activists worked to restore her proper place in civil rights history.

Colvin’s story reminds us that movements depend on people willing to act even when recognition never comes.

Bessie Coleman

American flight schools slammed their doors in her face. Bessie Coleman refused to accept that answer, so she learned French and moved to France in 1920.

Within a year, she earned her international pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, becoming the first Black woman to hold any pilot’s license.

Coleman returned home as “Queen Bess,” thrilling crowds with daredevil stunts and parachute jumps. She walked away from events that enforced segregation, insisting her shows be open to everyone.

Her barnstorming tours across the country inspired countless young people who had never imagined Black women could fly.

She dreamed of opening a flight school for African Americans, working tirelessly to save money for that goal. Tragically, a plane malfunction during a test flight took her life in 1926 when she was just 34 years old.

The wrench that caused the crash was never supposed to be there.

Her legacy soared beyond her lifetime. Aviators and activists kept her memory alive, and today flight clubs, scholarships, and even a Chicago street bear her name.

Coleman proved that determination could break through any barrier.

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer grew up picking cotton in Mississippi’s Delta, finishing only six grades of school. When she tried to register to vote in 1962, she lost her job and faced brutal retaliation.

Instead of retreating, she became one of the most powerful voices for voting rights in America.

Her testimony at the 1964 Democratic National Convention stopped the nation cold. She described being beaten in a Mississippi jail so severely that her body never fully recovered.

President Johnson tried to interrupt her speech with a hastily called press conference, but networks replayed her words in full that night.

Hamer co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the all-white delegation sent to represent her state. Though they didn’t win full recognition in 1964, their challenge forced the Democratic Party to change its rules.

By 1968, integrated delegations became mandatory.

She fought for economic justice too, establishing cooperatives and affordable housing projects in rural Mississippi. Her famous line “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired” captured the exhaustion and determination of millions.

Hamer showed that formal education couldn’t measure someone’s ability to change history.

Ella Baker

Behind every major civil rights organization of the 20th century, you’ll find Ella Baker’s fingerprints. She worked with the NAACP for over a decade, then helped establish the Southern Christian Leadership Conference alongside Martin Luther King Jr. Her organizing philosophy centered on developing leaders rather than following them.

Baker believed in grassroots democracy, trusting ordinary people to solve their own problems. When student sit-ins erupted across the South in 1960, she organized the conference that launched SNCC.

She encouraged students to form their own organization rather than becoming a youth wing of existing groups.

Her approach clashed with the top-down leadership style of many male civil rights leaders. Baker pushed for group-centered leadership and participatory democracy, ideas that shaped activist movements for generations.

She mentored countless young organizers who went on to lead major campaigns.

Baker worked into her 80s, connecting civil rights struggles to broader fights for human rights and economic justice. She rarely sought the spotlight, preferring to build power from the bottom up.

Her quote “Strong people don’t need strong leaders” became a rallying cry for democratic organizing. Without Baker’s vision, the Civil Rights Movement would have looked completely different.

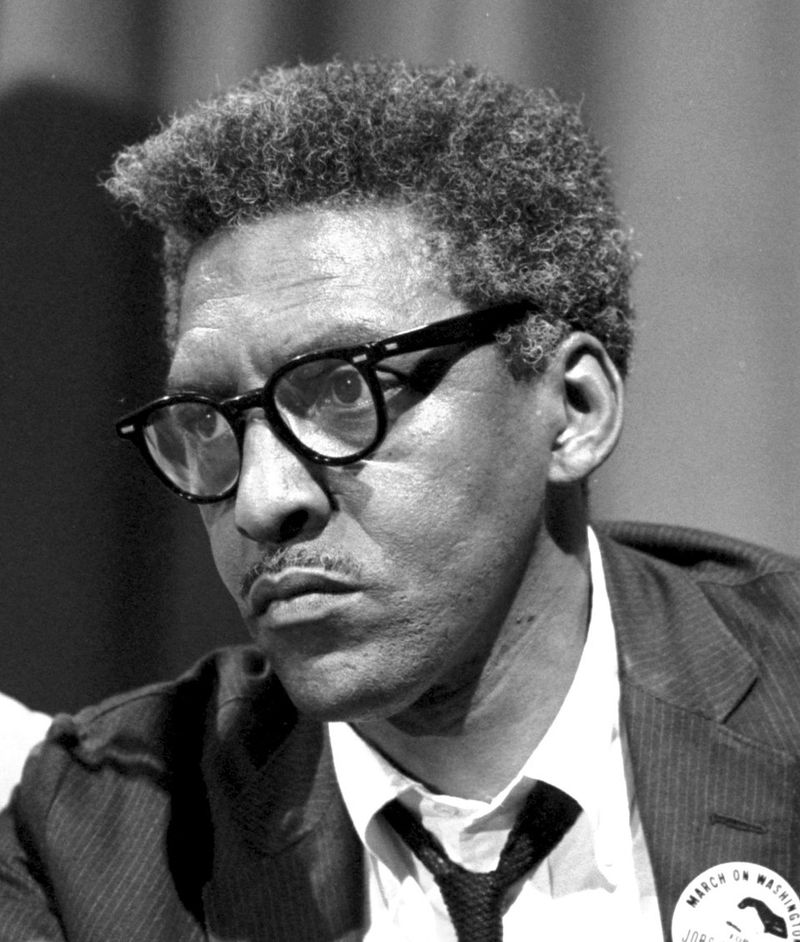

Bayard Rustin

The 1963 March on Washington brought 250,000 people to the National Mall without major incident. That logistical miracle happened because Bayard Rustin spent months planning every detail, from portable toilets to sound systems to marshals trained in nonviolent crowd management.

He was a genius at turning protest into precision.

Rustin introduced Martin Luther King Jr. to Gandhian nonviolence, shaping the philosophical foundation of the Civil Rights Movement. He organized the Journey of Reconciliation in 1947, an early Freedom Ride that tested desegregation laws.

His strategic brilliance influenced nearly every major campaign of the era.

Yet his name rarely appears in textbooks. As an openly gay man in a deeply homophobic time, Rustin faced constant pressure to stay in the background.

Movement leaders worried that his sexuality would give opponents ammunition, so his contributions were systematically minimized. Senator Strom Thurmond even attacked him on the Senate floor.

Rustin refused to hide who he was, even when it cost him recognition. Later in life, he became an advocate for LGBTQ rights, connecting it to broader struggles for human dignity.

His exclusion from history books reflects the same prejudice he fought against throughout his remarkable career.

Marsha P. Johnson

Marsha P. Johnson handed out flowers in Greenwich Village and stood up when it mattered most.

Present during the Stonewall uprising in June 1969, she became an icon of LGBTQ resistance. Her full name—Marsha “Pay It No Mind” Johnson, reflected her attitude toward people who questioned her gender identity.

Johnson and Sylvia Rivera co-founded STAR in 1970, one of the first organizations dedicated to helping homeless LGBTQ youth. They literally opened their own apartment as a shelter when no one else would help trans youth surviving on the streets.

STAR fought for the most marginalized members of the queer community, people often ignored even by other activists.

She participated in early Pride marches and continued organizing throughout the 1970s and 80s. Johnson also became an AIDS activist with ACT UP, providing care and support during the height of the epidemic.

Her joy and resilience inspired everyone around her, even as she faced constant discrimination and violence.

In 1992, her body was found in the Hudson River under suspicious circumstances. Police quickly ruled it suicide, but friends and activists suspected foul play.

Decades later, her case was reopened as a possible homicide. Johnson’s life and mysterious death highlight both the power and vulnerability of trans activists.

Dorothy Height

Dorothy Height stood on the stage at the March on Washington, but organizers didn’t let her speak. As the only woman on the planning committee and president of the National Council of Negro Women, she had earned the platform.

The slight demonstrated exactly why her work mattered so much.

For 40 years, Height led the NCNW, pushing both civil rights and women’s rights forward simultaneously. She organized campaigns against lynching, fought for fair employment, and championed childcare and education programs.

Her work connected struggles that others tried to separate, showing how racism and sexism reinforced each other.

Height advised every president from Eisenhower to Obama on civil rights issues. She helped organize the 1963 March alongside Rustin and other leaders, even if she couldn’t deliver a speech.

Her behind-the-scenes influence shaped major legislation and social programs for decades.

She received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994 and the Congressional Gold Medal in 2004. Height continued working past her 90th birthday, mentoring young activists and writing about her experiences.

Her autobiography revealed the constant battles she fought to keep women’s voices centered in civil rights work. She understood intersectionality before the term existed, living it every day of her remarkable life.

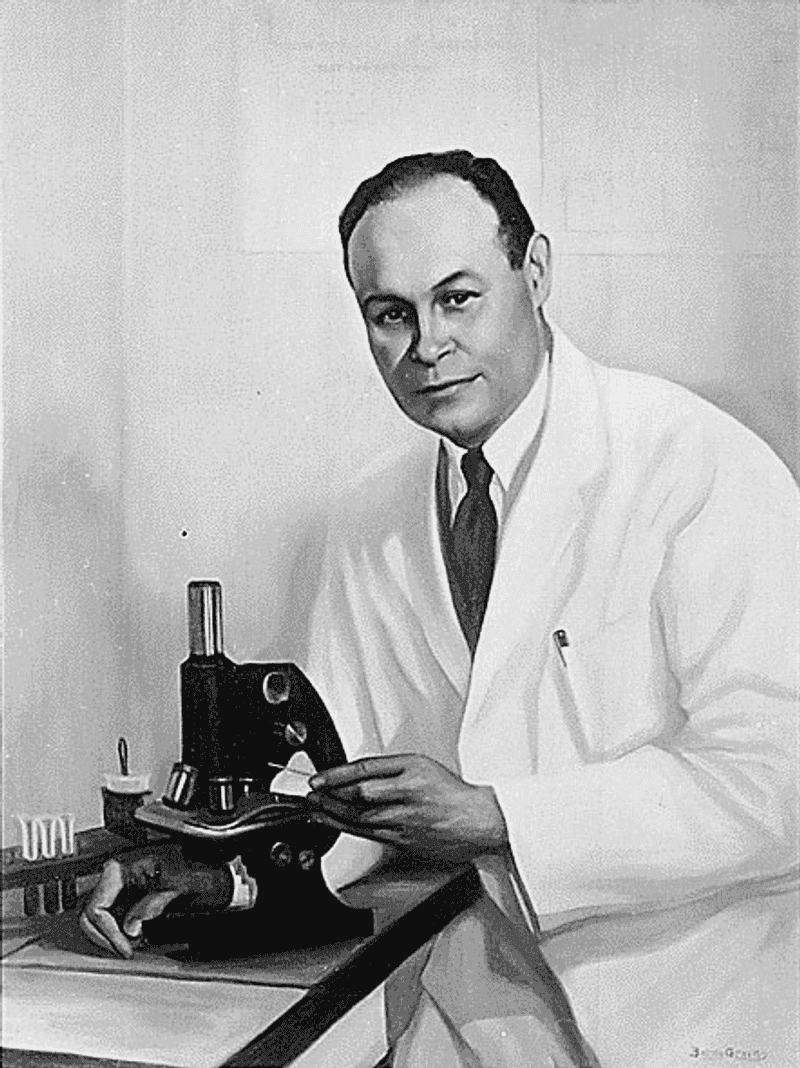

Charles Drew

Dr. Charles Drew figured out how to keep blood plasma stable for long periods, revolutionizing emergency medicine. His research during World War II helped establish blood banks and collection systems that saved countless lives.

He directed the “Blood for Britain” program in 1940 and later led the American Red Cross blood bank.

Ironically, the Red Cross initially refused to accept blood from Black donors. When they finally agreed, they segregated blood by race, a policy Drew publicly called unscientific and insulting.

He resigned from his position rather than support the discriminatory practice, sacrificing his career advancement for principle.

Drew returned to Howard University as chief surgeon and professor, training the next generation of Black physicians. He became an expert in trauma surgery and surgical techniques, publishing research that advanced the field.

His students went on to break barriers in medicine across the country.

A car accident took his life in 1950 at just 45 years old. Rumors spread that segregated hospitals refused to treat him, though evidence suggests he received immediate care.

The myth persists because it reflected a horrible truth about segregated medicine. Drew’s legacy lives on in every blood drive and emergency transfusion, proof that scientific excellence transcends prejudice.

Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson’s voice could fill any concert hall without amplification. He became an international star as a singer and actor, performing Shakespeare and spirituals with equal brilliance.

His rendition of “Ol’ Man River” became legendary, though he changed the lyrics to protest racial injustice.

Robeson used his fame to fight for civil rights, labor rights, and anti-colonial movements worldwide. He spoke out against fascism in the 1930s and defended the Spanish Republic.

His political activism and sympathy for socialism made him a target during the Cold War era.

The U.S. government revoked his passport in 1950, essentially trapping him in America for eight years. Concert venues canceled his performances under pressure from anti-communist groups.

The FBI maintained a massive file on him, tracking his every move and working to destroy his career.

Robeson never backed down from his beliefs, even as blacklisting devastated his income and reputation. When he finally regained his passport in 1958, he toured internationally to massive crowds.

His persecution illustrated how the government punished Black activists who connected American racism to global struggles. Robeson sacrificed his career rather than compromise his principles, paying an enormous price for his courage.

Claudia Jones

Claudia Jones connected dots that others missed, linking racism, sexism, and economic exploitation in her writing and organizing. Born in Trinidad, she moved to Harlem and became a communist organizer and journalist.

Her essay “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman” became foundational to later intersectional feminist thought.

The U.S. government deported her in 1955 during the McCarthy era, citing her communist party membership. She landed in Britain, where she immediately started organizing Caribbean communities facing discrimination and poverty.

Rather than retreating from activism, she doubled down.

Jones founded the West Indian Gazette in 1958, creating Britain’s first major Black newspaper. The publication covered issues mainstream media ignored, from police brutality to housing discrimination.

She also helped launch what became the Notting Hill Carnival, organizing indoor Caribbean festivals that evolved into London’s massive annual celebration.

Jones died in 1964 at just 49, her health weakened by years of poverty and political persecution. She was buried in Highgate Cemetery, near Karl Marx, a testament to her ideological commitments.

Her journalism and organizing laid groundwork for Black British activism that continues today. Jones proved that deportation couldn’t silence someone determined to fight for justice.

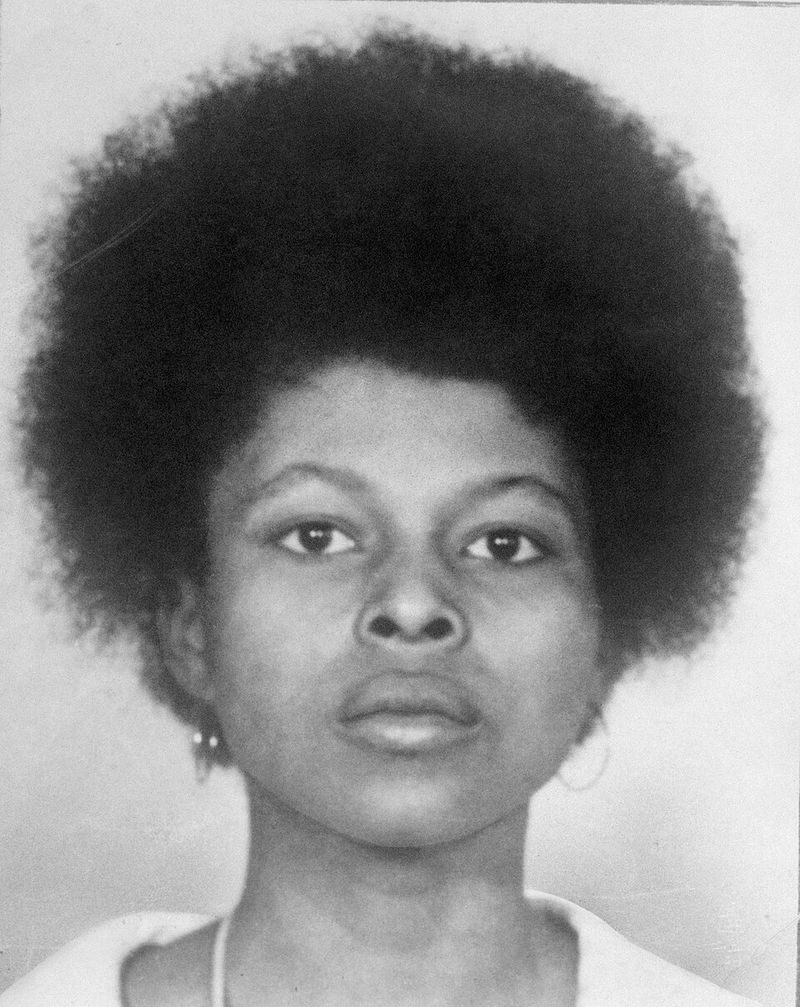

Assata Shakur

Assata Shakur’s story remains intensely controversial. Born Joanne Chesimard, she became active in the Black Panther Party and Black Liberation Army during the 1970s.

In 1973, a shootout on the New Jersey Turnpike left State Trooper Werner Foerster dead and Shakur wounded.

Her 1977 trial and conviction generated fierce debate. Supporters claimed she was targeted for her political activism and couldn’t have fired the fatal shots based on her injuries.

Prosecutors presented evidence linking her to the crime. The jury convicted her of murder, and she received a life sentence.

In 1979, Shakur escaped from prison with help from supporters and eventually reached Cuba. Fidel Castro’s government granted her political asylum, where she has lived ever since.

In 2013, the FBI added her to its Most Wanted Terrorists list, offering a million-dollar reward.

Her case crystallizes debates about political prisoners, revolutionary violence, and government repression of Black activists. Shakur’s autobiography became required reading for many studying Black liberation movements.

Some view her as a freedom fighter wrongly convicted; others see a cop killer who escaped justice. Her exile in Cuba continues, making her simultaneously a symbol of resistance and a fugitive from American law.

Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston traveled through the rural South with a notebook and recording equipment, capturing stories, songs, and folklore that might have been lost forever. Trained as an anthropologist, she documented Black Southern culture with respect and scholarly rigor.

Her fieldwork preserved traditions that white academics had dismissed as unworthy of study.

Hurston published seven books during her lifetime, including the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God in 1937. The book told a Black woman’s story in her own voice, using dialect and vernacular that many critics initially dismissed.

It explored love, independence, and self-discovery with a complexity rarely seen in literature of that era.

Despite her talent, Hurston struggled financially for most of her life. Publishers paid her poorly, and her work fell out of print.

She died in poverty in 1960 and was buried in an unmarked grave in Florida. For years, her contributions were nearly forgotten.

Alice Walker revived interest in Hurston’s work in the 1970s, even placing a headstone on her grave. Today, Their Eyes Were Watching God is recognized as a masterpiece of American literature.

Hurston’s anthropological work influenced how we understand and value African American cultural traditions, proving that academic excellence and cultural pride could coexist beautifully.