How deep have humans actually drilled into Earth, and what did we learn along the way? This list brings together record breaking boreholes, oil wells, and ultra deep mines that push technology and people to their limits.

You will see how geology, engineering, and practical goals like energy and minerals shaped each project. If you enjoy clear facts, credible context, and straight answers, this guide delivers exactly that.

1. Kola Superdeep Borehole (Russia) – ~12.3 km

The Kola Superdeep Borehole reached about 12.3 kilometers, making it the deepest human made hole by true vertical depth. It was a Soviet scientific project launched to study Earth’s continental crust, not to extract resources.

Engineers discovered unexpectedly porous rocks at depth and water bound in minerals, challenging existing models.

Temperatures soared near 180 degrees Celsius, which limited drilling progress and tool life. Rock at those depths behaved plastically, causing borehole stability problems and frequent equipment failures.

Many core samples revealed complex metamorphic histories, including ancient granites and signs of microfossils in shallower layers.

You will not see a dramatic open shaft today, just a sealed cap on a quiet site. The project paused in the 1990s as funding and technical headroom faded.

Its data helped refine seismic interpretations, offering ground truth for crustal layering and the nature of the Mohorovicic discontinuity.

2. Al Shaheen Oil Well (Qatar) – ~12.3 km+ (extended reach)

Al Shaheen’s extended reach wells achieved total measured lengths beyond 12 kilometers, pushing horizontal drilling limits. Unlike vertical superdeep science holes, these wells travel laterally through reservoirs to contact more productive rock.

The feat depends on rotary steerable systems, precise geosteering, and robust drillstring design.

High friction from long wellbores demands advanced lubricants and torque and drag management. Downhole tools relay real time data so directional drillers can adjust trajectory and keep within thin target zones.

Managed pressure drilling helps balance formation pressures while protecting hole integrity.

For you as a reader, the big takeaway is how reach, not just depth, drives modern oil productivity. These wells maximize reservoir exposure without adding risky vertical kilometers.

The result is better recovery from offshore fields while controlling costs and environmental footprint relative to multiple platforms.

3. Sakhalin-1 Wells (Russia) – ~12+ km (extended reach)

The Sakhalin-1 project set repeated records for total measured depth and horizontal stepout, topping 12 kilometers on multiple wells. Drilled from land to offshore reservoirs, these wells minimize offshore structures in harsh subarctic seas.

Directional drilling teams rely on rotary steerable systems and real time logging while drilling.

Challenges include low temperatures, sea ice conditions, and complex geomechanics in stacked reservoirs. Long laterals increase cuttings transport difficulty, so high rate mud circulation and optimized rheology are crucial.

Casing and liner strings must withstand thermal cycles and pressure while maintaining integrity across extended sections.

You gain insight into how engineering adapts to geography. By staying onshore, operators reduce exposure to storms and ice, yet still reach far beneath the seafloor.

The project illustrates the blend of logistics, data, and hardware behind record breaking well paths.

4. BD-04A (Bertha Rogers) (USA, Oklahoma) – ~9.6 km

The Bertha Rogers well in Oklahoma, designated BD-04A, reached roughly 9.6 kilometers in the early 1970s. It pursued deep gas targets in the Anadarko Basin, an ambitious goal for that era’s materials and tools.

At extreme depths, the well encountered high pressures, high temperatures, and unexpectedly hard formations.

Legend notes drillpipe twisting off and bit failures as routine risks. Ultimately, the well famously hit a thick layer of molten sulfur that complicated operations and economics.

Although not a commercial success, it pushed U.S. drilling technology forward and informed later deep programs.

If you are comparing records, remember this is true vertical drilling rather than long horizontal reach. The project’s legacy lies in metallurgy improvements, mud systems for high temperature, and pressure control lessons.

It remains a landmark in continental deep drilling history.

5. KTB Superdeep Borehole (Germany) – ~9.1 km

Germany’s KTB project drilled to about 9.1 kilometers to study the continental crust under controlled scientific protocols. It combined a pilot hole with a main bore, generating extensive cores, logs, and seismic tie data.

Researchers observed high in situ temperatures near 265 degrees Celsius and significant fluid presence at depth.

Seismic anisotropy, fracture networks, and conductive zones were key findings that recalibrated models of crustal permeability. The site supported experiments on stress, microseismicity, and fluid flow in crystalline rock.

Advanced mud systems and robust drillstrings were essential to cope with heat and mechanical stress.

For you, KTB underscores how science boreholes complement oil and gas technology. The data sharpened interpretations used across Europe for geothermal and structural assessments.

Even without commercial production, it delivered a durable public dataset and training ground for deep drilling methods.

6. Deepwater Horizon / Macondo Well (USA, Gulf of Mexico) – ~5.5–6.4 km total depth

The Macondo well’s total depth was in the roughly 5.5 to 6.4 kilometer range, depending on reference measures. Drilled in about 1.5 kilometers of water, it extended several kilometers below the seafloor.

The project is widely known due to the 2010 blowout and subsequent environmental disaster.

From an engineering view, Macondo illustrates deepwater risks around pressure control, cementing, and barrier verification. Complex geology, narrow drilling margins, and operational decisions converged into a catastrophic failure.

Investigations reshaped industry practices on well design, testing, and real time monitoring.

When you think depth, remember measured depth and true vertical depth differ, especially offshore. The event accelerated improvements in blowout preventers, emergency response, and containment systems.

Its legacy is a stronger focus on safety culture and transparent reporting across offshore operations.

7. Cajon Pass Scientific Drill Hole (USA, California) – ~3.5 km

The Cajon Pass drill hole reached about 3.5 kilometers to study heat flow, fluid movement, and crustal properties near major faults. Located by a key transportation corridor, it provided a controlled look into Southern California’s geologic framework.

The project emphasized temperature gradients and rock property measurements over resource extraction.

Data from cores and logs helped refine thermal models of the crust and understand how fluids may circulate along fractures. Borehole stability and instrumentation survivability were important challenges in the hotter, deeper sections.

Careful mud programs and staged casing preserved a viable scientific observatory.

For readers, Cajon Pass shows how moderate depth drills can answer big geoscience questions. The results inform seismic hazard assessments and geothermal potential.

It stands as a practical bridge between shallow field studies and the ultra deep research like KTB and Kola.

8. San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth (SAFOD) (USA) – ~3.2 km

SAFOD drilled to roughly 3.2 kilometers to directly sample and monitor the San Andreas Fault. It sidetracked into the active fault zone, retrieving rare core samples of fault gouge and damaged rock.

The project installed long term sensors to capture microseismicity and physical changes near the fault.

Drilling into a fault required careful trajectory control, strong casing programs, and pressure management. Scientists analyzed mineral assemblages, clay content, and frictional properties to evaluate earthquake mechanics.

Continuous monitoring yielded insights into creep behavior and stress changes over time.

You get a rare window into earthquake science from downhole data rather than distant sensors. SAFOD’s curated samples let labs test real fault materials, not just analogs.

The observatory improved models of rupture nucleation, informing risk assessments for communities along the fault.

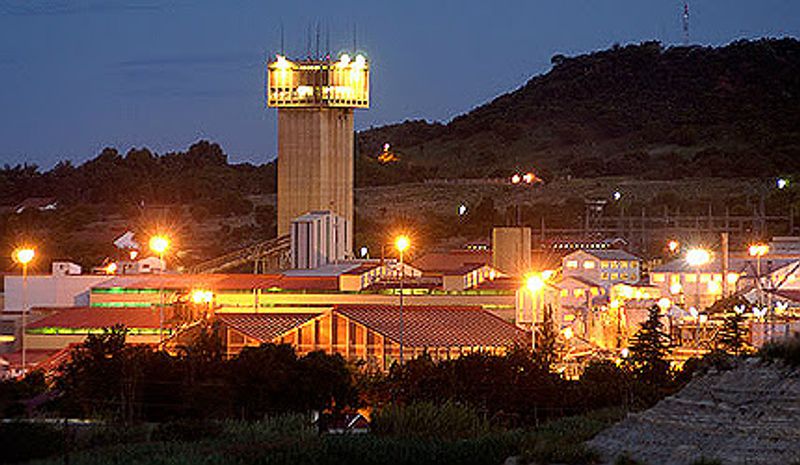

9. Mponeng Gold Mine (South Africa) – ~4.0 km

Mponeng descends to about 4 kilometers, making it one of the world’s deepest mines. Unlike a borehole, it is a network of shafts, tunnels, and stopes accessing gold bearing reefs.

Temperatures rise quickly, so chilled water and ventilation keep working conditions within limits.

Rockbursts and seismicity are ongoing hazards at such depth, requiring support systems and careful sequencing. Ore is hauled from stopes to surface using hoists, conveyors, and rail.

Efficiency depends on meticulous planning, since travel times and logistics compound with depth.

For you, the depth translates to real human endurance and engineering discipline. Mponeng showcases how geology, safety, and economics intersect underground.

It remains a benchmark for deep level mining innovation, from cooling systems to microseismic monitoring.

10. TauTona Gold Mine (South Africa) – ~3.9 km

TauTona, part of the West Wits goldfield, reached roughly 3.9 kilometers below surface. Operations pushed heat, pressure, and stress limits similar to neighboring deep mines.

Extensive refrigeration plants circulate chilled brine to reduce ambient temperatures in active areas.

Seismic monitoring guides layout decisions to mitigate rockburst risk around stopes and pillars. Support includes rock bolts, mesh, and shotcrete in critical excavations.

Production planning balances safety, ore grade, and ground conditions while keeping haulage efficient over great distances.

As a reader, you can picture long shift journeys, strict protocols, and precise scheduling. TauTona exemplifies how deep mines depend on data and discipline.

Its lessons persist in ventilation design, worker safety practices, and the economics of marginal grade at depth.

11. Moab Khotsong Gold Mine (South Africa) – ~3.2 km

Moab Khotsong reaches near 3.2 kilometers, combining deep level mining with modern monitoring. It targets high grade portions of the Vaal Reef, where narrow veins demand accurate drilling and blasting.

Cooling systems and ventilation networks handle high rock temperatures.

Stress management uses sequential extraction, regional pillars, and careful stope sequencing. Data from extensometers and microseismic sensors guide decisions in near real time.

Hoisting systems move ore and personnel efficiently across multiple shaft compartments.

For readers, the mine shows how incremental improvements add up at depth. Efficiency, safety, and ore recovery depend on coordinated planning more than any single technology.

The operation underscores how deep South African mines remain complex, data heavy enterprises.

12. Kidd Creek Mine (Canada) – ~3.0 km

Kidd Creek in Ontario extends to around 3 kilometers and is among the deepest base metal mines. It produces copper, zinc, and silver from a volcanogenic massive sulfide deposit.

Deep mining conditions require strong ground support and sophisticated ventilation to manage heat and diesel particulates.

Geology includes complex folding and faulting, so mapping and geophysics assist with orebody definition. Paste backfill supports mined out stopes, allowing safer extraction of adjacent blocks.

Hoisting systems and ore passes link lower levels to the surface mill.

For you, Kidd Creek demonstrates deep mining outside South Africa’s goldfields. The challenges are similar, but the ore type and mining methods differ.

Its longevity reflects adaptive planning, from backfill engineering to energy efficient ventilation strategies in cold climates.

13. Creighton Mine (Canada) – ~2.5 km

Creighton Mine near Sudbury reaches about 2.5 kilometers and is known for nickel, copper, and associated metals. The deposit lies within the Sudbury Basin, a large impact related structure.

Depth brings heat and stress, prompting robust ground support and targeted cooling in active headings.

Creighton is also associated with the nearby SNOLAB research facility, which benefits from the great overburden for cosmic ray shielding. Mining uses bulk and selective methods depending on ore geometry.

Backfill and sequencing stabilize openings as extraction proceeds deeper.

For readers, Creighton highlights how industrial mining can coexist with world class science underground. The mine’s engineering keeps operations safe while supporting a unique laboratory environment.

It stands as a case study in deep operations within a historically rich mining district.