Throughout history, entire cities have vanished beneath jungles, deserts, oceans, and volcanic ash, erased from memory for centuries or even millennia. Some were dismissed as myths, while others simply faded from maps as civilizations crumbled and nature reclaimed what humans built.

Yet through the determined work of archaeologists, explorers, and sometimes sheer luck, these forgotten places have been brought back into the light, revealing astonishing stories of ancient cultures and lost worlds. Join us as we explore remarkable cities that disappeared from history, only to be rediscovered and shared with the world once more.

Machu Picchu — The Inca Citadel Forgotten in the Clouds

Perched on a narrow ridge between towering Andean peaks, Machu Picchu remained concealed from the world for nearly 400 years. U.S. historian Hiram Bingham stumbled upon the site in 1911 while searching for a different lost city, guided by local farmers who knew of the ruins.

Built around 1450 by the Inca emperor Pachacuti, this stone marvel showcases the empire’s extraordinary engineering prowess. Massive granite blocks fit together without mortar, forming temples, palaces, and agricultural terraces that cling to impossibly steep slopes.

Ingenious water channels still function today, testament to Inca hydraulic mastery. Why the city was abandoned remains a mystery, though scholars suspect smallpox and Spanish conquest pressures played roles.

Dense jungle vegetation swallowed the site whole, hiding it from Spanish conquistadors who never found this mountain sanctuary. Bingham’s photographs and writings brought international fame to Machu Picchu, transforming it into Peru’s most visited attraction.

Today, travelers from across the globe trek the Inca Trail to witness sunrise over the ancient citadel. The site’s dramatic setting and architectural brilliance continue to inspire wonder, making it an enduring symbol of pre-Columbian achievement and one of history’s most spectacular rediscoveries.

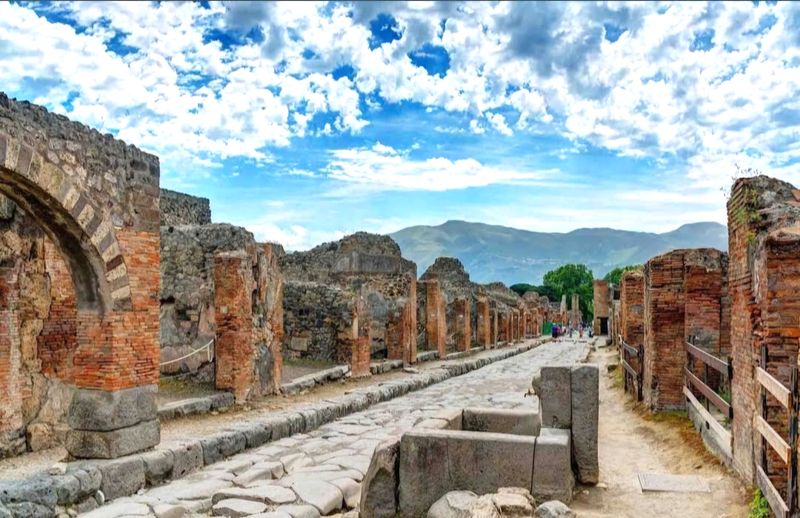

Pompeii — Frozen by Vesuvius, Found by Accident

When Mount Vesuvius erupted violently in 79 AD, it buried Pompeii under 20 feet of volcanic ash and pumice within hours. Roughly 2,000 residents perished, their final moments captured in haunting plaster casts created by archaeologists centuries later.

The city’s location faded from collective memory until 1748, when workers digging a well accidentally uncovered ancient walls. Systematic excavations revealed an astonishingly preserved snapshot of Roman daily life—bakeries with loaves still in ovens, taverns with wine amphorae, and homes adorned with vibrant frescoes.

Unlike typical archaeological sites where only foundations survive, Pompeii offers complete buildings, furnishings, and personal belongings. Graffiti scrawled on walls provides intimate glimpses into residents’ thoughts, jokes, and complaints.

Even food remains were preserved, revealing Roman dietary habits. The rediscovery fundamentally changed how historians understand ancient Rome, shifting focus from emperors and battles to ordinary citizens’ experiences.

Visitors today walk the same streets Romans trod two millennia ago, entering homes and public baths frozen in time. Pompeii’s tragic destruction became archaeology’s greatest gift, offering an unparalleled window into antiquity that continues yielding new discoveries with each excavation season.

Troy — Legendary City Vindicated

For centuries, scholars dismissed Homer’s Iliad as pure fiction, believing Troy existed only in poetic imagination. That changed when German businessman Heinrich Schliemann began excavating a mound called Hisarlik in northwestern Turkey during the 1870s.

Schliemann’s methods were crude by modern standards—he actually dug through several important layers seeking Homer’s city. Yet his discoveries proved undeniably significant: multiple cities built atop one another over thousands of years, with massive fortification walls and evidence of violent destruction.

Archaeologists now recognize at least nine distinct settlement layers at Troy, spanning from 3000 BC to Roman times. Troy VII, dating to approximately 1200 BC, shows burn marks and scattered weapons consistent with the legendary Trojan War period described in ancient texts.

The rediscovery transformed understanding of Bronze Age Aegean civilizations and the historical kernel within Greek mythology. Troy controlled vital shipping routes between the Mediterranean and Black Sea, making it strategically valuable enough to spark real conflicts.

Modern excavations continue revealing Troy’s connections to Mycenaean Greece and Hittite Anatolia. What began as myth now stands as verified history, demonstrating how archaeological persistence can resurrect entire civilizations from the realm of legend.

Petra — The Rose City of Jordan

Carved directly from rose-hued sandstone cliffs, Petra served as the Nabataean Kingdom’s capital from approximately 300 BC onward. This desert metropolis thrived on caravan trade routes carrying frankincense, myrrh, and spices between Arabia and the Mediterranean world.

After earthquakes and shifting trade patterns caused Petra’s decline, the city vanished from Western awareness for over a thousand years. Local Bedouin tribes knew of the ruins but kept them secret from outsiders.

Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt finally revealed Petra to Europe in 1812 by disguising himself as an Arab scholar. The iconic Treasury facade—featured in countless photographs and films—represents just a fraction of Petra’s wonders.

Over 800 monuments fill the site, including elaborate tombs, a massive amphitheater, temples, and sophisticated water management systems that sustained thousands in the arid landscape. Nabataean engineers carved channels and cisterns throughout the rock, controlling flash floods and storing precious rainwater.

Their architectural genius blended Hellenistic, Egyptian, and indigenous Arabian influences into a unique style. Today, Petra ranks among the world’s most visited archaeological sites, its rediscovery opening windows into Arabian civilization’s sophistication and the ingenuity required to build magnificent cities where water scarcely exists.

Ciudad Perdida — Colombia’s Lost City in the Sierra Nevada

Deep within Colombia’s Sierra Nevada mountains, treasure hunters stumbled upon stone terraces in 1972 while searching for gold. What they found proved far more valuable historically—an extensive urban settlement predating Machu Picchu by approximately 650 years.

Built around 800 AD by the Tairona people, Ciudad Perdida (known originally as Teyuna) consisted of over 170 terraced platforms connected by stone stairways and paths. At its peak, roughly 2,000 to 8,000 people inhabited this cloud forest metropolis, cultivating crops on hillside terraces and trading with coastal communities.

The city was abandoned during the Spanish conquest as indigenous populations fled disease and violence. Jungle vegetation swallowed the site so completely that even local communities forgot its precise location.

After looters began removing artifacts in the 1970s, Colombian authorities intervened, launching proper archaeological investigations. Reaching Ciudad Perdida requires a challenging multi-day trek through dense rainforest, fording rivers and climbing steep mountain paths.

Unlike heavily touristed Machu Picchu, this lost city retains an air of remote adventure. Indigenous Kogi, Wiwa, Arhuaco, and Kankuamo peoples—descendants of the Tairona—still consider the site sacred.

Their ongoing presence connects modern visitors to living traditions stretching back over a millennium.

Hattusa — Capital of the Hittite Empire

Once rivaling Egypt and Mesopotamia in power, the Hittite Empire dominated Anatolia during the Bronze Age. Its capital, Hattusa, commanded a strategic plateau in central Turkey, protected by massive stone fortifications stretching over six kilometers.

Around 1200 BC, the empire collapsed during the mysterious Bronze Age crisis that toppled civilizations across the Mediterranean. Hattusa was violently destroyed and abandoned, its very existence fading from historical memory except for scattered biblical references to “Hittites.” French archaeologist Charles Texier rediscovered the ruins in 1834, though their true significance remained unclear until German excavations began in 1906.

Archaeologists unearthed thousands of cuneiform clay tablets—the royal archives—revealing diplomatic correspondence, legal codes, religious texts, and treaties including one with Egypt’s Ramesses II. These tablets resurrected an entire civilization, demonstrating the Hittites’ sophisticated administration, advanced metallurgy, and crucial role in ancient Near Eastern politics.

Hattusa’s excavated remains include temples, palaces, fortification gates adorned with lion and sphinx sculptures, and an underground tunnel system. The site’s rediscovery fundamentally revised Bronze Age history, filling gaps between better-known Egyptian and Mesopotamian records.

Today, visitors walk among ruins that once housed kings who corresponded as equals with pharaohs, exploring a capital that shaped ancient world politics before vanishing for three millennia.

Chan Chan — Peru’s Adobe Metropolis

Sprawling across 20 square kilometers of Peru’s arid coast, Chan Chan once housed an estimated 60,000 residents, making it pre-Columbian America’s largest adobe city. The Chimú civilization built this marvel between 850 and 1470 AD, before Inca conquest absorbed their kingdom.

Nine great citadels dominate the site, each serving as a royal compound with palaces, temples, gardens, and reservoirs. High adobe walls adorned with intricate geometric friezes and animal motifs surrounded these elite districts, while commoners lived in simpler dwellings beyond.

After Spanish conquest and subsequent abandonment, Chan Chan deteriorated under coastal weather and periodic El Niño floods. Looters ransacked tombs seeking gold and silver, while erosion wore away unprotected adobe structures.

The site’s scale and significance were only fully appreciated when systematic archaeological work began in the 20th century. Excavations revealed sophisticated urban planning adapted to desert conditions, including complex irrigation networks channeling water from distant rivers.

Artisans’ quarters showed specialized craft production—metalworking, weaving, and pottery—supporting a hierarchical society ruled from these adobe palaces. Today, Chan Chan faces ongoing conservation challenges as rain and wind continue eroding fragile earthen walls.

Yet the rediscovered city demonstrates that monumental architecture didn’t require stone—skilled hands could transform humble mud into a metropolis rivaling any ancient capital.

Mohenjo-Daro — Indus Valley Urban Puzzle

Buried beneath Pakistani soil for over 3,500 years, Mohenjo-Daro emerged in 1922 when archaeologist R.D. Banerji investigated Buddhist-era ruins and discovered far older structures beneath.

What he found revolutionized understanding of ancient South Asian civilization. Built around 2500 BC, Mohenjo-Daro exemplifies the Indus Valley Civilization’s remarkable urban sophistication.

The city follows a precise grid layout with main streets running north-south and east-west—a level of planning not seen in contemporary Mesopotamian or Egyptian cities. Multi-story brick houses featured private wells and bathrooms connected to covered drainage systems more advanced than those in many medieval European cities.

The Great Bath, a large public water tank, suggests ritual bathing held cultural importance. Granaries, assembly halls, and workshops indicate complex economic organization.

Yet Mohenjo-Daro presents enduring mysteries: no temples or palaces have been definitively identified, and the Indus script remains undeciphered. The city was abandoned around 1900 BC for reasons still debated—climate change, river shifts, or social upheaval may have contributed.

Its rediscovery challenged colonial-era assumptions that South Asian civilization began with Aryan migrations. Instead, Mohenjo-Daro proved indigenous cultures had created one of antiquity’s most advanced urban centers, trading with Mesopotamia and developing technologies independently millennia before previously believed.

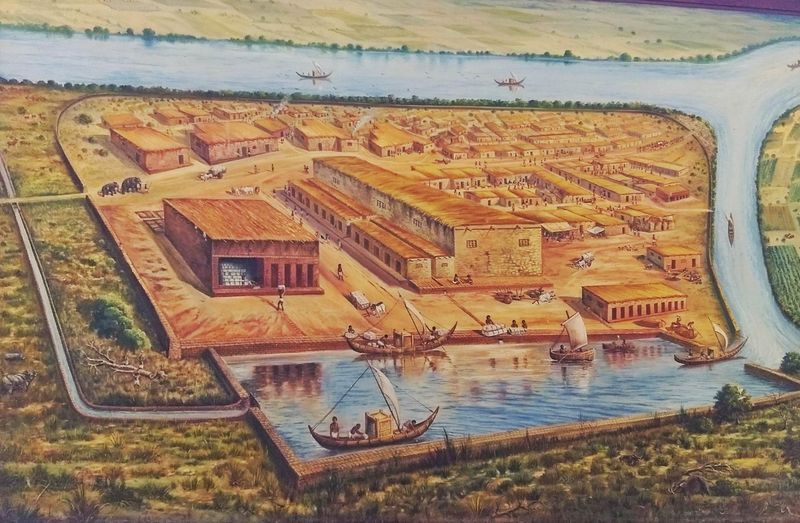

Lothal — Ancient Port of the Indus

Discovered in 1954 near India’s Gulf of Khambhat, Lothal revealed the Indus Valley Civilization’s maritime prowess. This port city, flourishing around 2400 BC, connected inland Harappan cities with sea trade routes extending to Mesopotamia and the Arabian Peninsula.

The site’s most remarkable feature is a massive dockyard—arguably the world’s earliest known—measuring 37 meters long and over 20 meters wide. Engineers designed this basin with a lockgate system allowing ships to enter during high tide and remain protected as waters receded.

Adjacent warehouses stored trade goods: carnelian beads, copper, shells, and precious stones. Excavations uncovered workshops producing standardized weights, measures, and seals identical to those found across the Indus civilization, demonstrating remarkable administrative uniformity across vast distances.

Bead-making factories showed specialized craft production for export markets. A Persian Gulf seal found at Lothal confirms long-distance maritime commerce.

The city’s sophisticated drainage, planned streets, and residential areas mirror larger Indus cities like Mohenjo-Daro, but Lothal’s compact size and specialized economy mark it as a dedicated trading hub. Its rediscovery transformed understanding of Bronze Age global trade networks and ancient seafaring capabilities.

Rising sea levels and flooding eventually forced Lothal’s abandonment around 1900 BC. Today, the preserved dockyard stands as testament to engineering ingenuity that enabled ancient mariners to connect distant civilizations across dangerous seas.

Vilcabamba — The Inca’s Last Refuge

After Spanish conquistadors toppled the Inca Empire in 1533, rebel Inca rulers retreated to Vilcabamba, a remote mountain stronghold where they maintained an independent state for nearly four decades. Spanish chroniclers wrote of this “lost city,” but its exact location remained unknown for centuries.

The last Inca emperor, Túpac Amaru, was captured and executed in 1572, and Vilcabamba was abandoned and swallowed by jungle. For generations, explorers searched without success, with some mistakenly believing Machu Picchu was the legendary refuge.

The breakthrough came in the 1960s when American explorer Gene Savoy investigated a site called Espíritu Pampa in Peru’s Vilcabamba region. Beneath dense vegetation, he found extensive Inca ruins matching Spanish descriptions—roof tiles indicating Spanish influence, and a layout consistent with a city built during resistance rather than the empire’s height.

Subsequent archaeological work confirmed Espíritu Pampa as Vilcabamba, the final Inca capital. The ruins reveal a city constructed hastily under siege conditions, lacking the refined stonework of earlier Inca architecture.

Spanish roof tiles show cultural blending even during conflict. Vilcabamba’s rediscovery completed the narrative of Inca resistance, revealing how the empire’s remnants survived decades longer than commonly believed.

The site remains relatively obscure compared to Machu Picchu, but historically represents the defiant final chapter of Andean independence.

Pavlopetri — The World’s Oldest Underwater City

Resting beneath three to four meters of water off southern Greece’s coast, Pavlopetri holds the distinction of being the world’s oldest known submerged city. Oceanographer Nicholas Flemming discovered the site in 1967 while surveying the seabed, finding remarkably intact streets, buildings, and courtyards dating back approximately 5,000 years.

The city thrived during the Bronze Age, roughly 2800 to 1100 BC, serving as a vital trade center. Its layout reveals sophisticated urban planning with distinct residential and commercial districts.

At least 15 separate buildings have been mapped, along with courtyards, streets, chamber tombs, and what appears to be a religious structure. Pavlopetri likely sank due to earthquakes—the region sits on active fault lines that have repeatedly reshaped coastlines.

Rising sea levels following the last Ice Age may have contributed. The underwater environment paradoxically preserved the city better than land-based sites, protecting it from modern development and agricultural damage.

Recent digital mapping using sonar and photogrammetry has created detailed 3D models, revealing features invisible to divers. Pottery fragments, stone tools, and other artifacts recovered from the seabed provide insights into Bronze Age Aegean life and trade networks.

Pavlopetri’s rediscovery opened an entirely new archaeological frontier—underwater cities that challenge researchers to develop innovative techniques for studying submerged heritage while preserving these fragile time capsules beneath the waves.

Ancient Submerged Cities of the Mediterranean

Beyond famous examples like Pavlopetri and Thonis-Heracleion, the Mediterranean seabed conceals dozens of lost settlements. Rising waters following the last Ice Age, combined with earthquakes and subsidence, drowned coastal communities across millennia.

Modern underwater archaeology continues revealing these forgotten worlds. Off Tunisia’s coast, the Roman city of Neapolis was rediscovered in 2017, submerged by a tsunami in the 4th century AD.

Streets, monuments, and fish-salting factories—the source of the city’s wealth—lie preserved underwater. Near Naples, Italy, the Roman resort town Baiae sank due to volcanic activity, its luxury villas and bath complexes now visited by snorkeling tourists.

In the Aegean, numerous Bronze Age settlements await discovery or further study. Climate change-induced sea level rise has submerged coastlines by over 100 meters since the Ice Age, potentially hiding countless prehistoric communities.

Each discovery rewrites understanding of ancient maritime cultures, trade routes, and coastal life. Technological advances enable archaeologists to survey vast underwater areas using sonar, remotely operated vehicles, and photogrammetry.

These tools have accelerated discovery rates, with new sites identified almost annually. Yet underwater excavation remains challenging—limited dive times, visibility issues, and preservation concerns complicate research.

These submerged cities offer unique preservation of organic materials like wood and rope that disintegrate on land. They provide snapshots of daily life frozen at the moment of catastrophe, revealing how ancient peoples adapted to living beside unpredictable seas.

Yaxchilan — Maya City of Mexico’s Lacandon Jungle

Hidden deep within Chiapas, Mexico’s Lacandon rainforest, Yaxchilan thrived as a powerful Maya city-state between 350 and 810 AD. Positioned strategically along the Usumacinta River, it controlled trade routes and engaged in alliances and conflicts with neighboring kingdoms like Palenque and Piedras Negras.

After the Classic Maya collapse around 900 AD, jungle vegetation consumed Yaxchilan’s plazas, temples, and palaces. The city remained unknown to outsiders until the late 19th century when explorers began documenting Maya sites.

Alfred Maudslay conducted the first systematic study in the 1880s, photographing intricately carved lintels and stelae. Yaxchilan’s stone monuments feature some of the finest Maya sculpture, depicting rulers in elaborate ceremonial dress performing bloodletting rituals and commemorating military victories.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions record dynastic histories spanning centuries, revealing political marriages, warfare, and religious ceremonies that bound Maya elite society. The site’s remote location preserved it from extensive looting, though some carved lintels were removed to museums.

Reaching Yaxchilan still requires boat travel along the Usumacinta, maintaining an atmosphere of adventure and discovery. Howler monkeys roar from surrounding trees as visitors explore temple complexes where Maya kings once performed rituals.

The rediscovery of Yaxchilan and similar jungle cities transformed understanding of Maya civilization’s complexity, revealing sophisticated kingdoms that flourished in environments Europeans once considered unsuitable for advanced cultures.