History loves to point a finger. But sometimes the story won’t sit still long enough to tell you who deserves the blame.

I felt that tension the first time I read about a ruler who bolted in the dark, leaving an army behind. Not a monster.

Not a hero. Just a person making a decision with limited information and a lot to lose.

That’s what makes these moments so hard to file away. Was it caution, or fear dressed up as strategy?

You can see it in the records, and you can almost hear it in the whispers that followed. A general orders a retreat.

A king disappears before sunrise. A leader chooses survival over spectacle, and suddenly everyone has an opinion.

In this list, we’re stepping into those split-second choices, from the battlefield to the palace corridor. One question that still won’t go away: were they saving themselves, or saving something bigger?

Charles Lee: Retreat or tactical reset?

Washington was furious. At Monmouth on that sweltering June day in 1778, Charles Lee pulled his troops back just as victory seemed within reach.

The resulting clash between the two generals became almost as famous as the battle itself.

Lee faced a court-martial and his military career never recovered. Critics called him a coward who panicked under British pressure.

His defenders argued he was being prudent, avoiding a trap that could have destroyed the Continental Army.

The debate rages on because Lee’s motives remain murky. Was he jealous of Washington?

Did he genuinely believe retreat was tactically sound? Or did fear override his judgment in the heat of combat?

What makes Lee’s case fascinating is how it captured the tension between boldness and caution in warfare. Sometimes a retreat saves an army.

Sometimes it loses a war. Lee’s pullback at Monmouth sits uncomfortably between those two possibilities, forever debated by historians who can never quite settle whether he was a careful tactician or simply scared.

Benedict Arnold: Ambition turned escape plan

Every American schoolkid learns Arnold’s name as the ultimate traitor. His 1780 plot to hand West Point to the British remains one of history’s most notorious betrayals.

When the scheme collapsed, he fled to British lines and never looked back.

Calling Arnold a coward seems almost too simple. Before his treason, he was arguably America’s most brilliant battlefield commander, leading daring assaults and taking serious wounds for the cause.

Something deeper than fear drove his betrayal.

Resentment festered as Congress passed him over for promotions. He faced corruption charges.

His marriage to a Loyalist sympathizer didn’t help. Arnold felt undervalued, insulted, and financially squeezed.

So was fleeing to the British cowardice or cold calculation? He saved his own skin, certainly, but he also believed he was backing the winning side.

His escape wasn’t a panic move but a planned exit strategy. Arnold’s story reminds us that cowardice and ambition can look remarkably similar when someone’s running for the door.

Edward II: Favorites first, kingdom last

Edward had terrible taste in friends. His relationship with Piers Gaveston enraged the nobility, who eventually executed Gaveston despite Edward’s desperate attempts to protect him.

Later favorites didn’t fare much better, and neither did Edward’s political position.

The king’s priorities baffled everyone. While England needed strong leadership, Edward seemed more interested in his personal relationships than governance.

His military failures, particularly the disastrous defeat at Bannockburn in 1314, shattered what remained of his authority.

Eventually, his own wife Isabella turned against him. She invaded England with her lover, deposed Edward, and imprisoned him.

His death in captivity remains mysterious and gruesome.

Was Edward a coward or just catastrophically unsuited to medieval kingship? He faced brutal factional pressure and made enemies at every turn.

But he also consistently chose personal comfort over political necessity. His reign suggests that sometimes weakness and cowardice are hard to distinguish from each other, especially when both lead to the same tragic ending.

Nero: Fiddling myth, real scapegoating

Nero probably didn’t fiddle while Rome burned in 64 CE. The fiddle didn’t even exist yet, and some sources suggest he wasn’t in the city when the fire started.

But the myth persists because it captures something true about his character.

What Nero definitely did was look for scapegoats after the Great Fire destroyed much of Rome. Christians made convenient targets.

His brutal persecution of this new religious group became legendary for its cruelty.

Blaming others instead of taking responsibility looks like moral cowardice. Nero needed someone to absorb public anger, so he picked a vulnerable minority.

Classic coward move, right?

Yet Nero also launched massive rebuilding efforts and opened his own gardens to displaced citizens. His response mixed genuine relief work with vicious scapegoating.

Maybe that’s the most cowardly part of all: doing some good things while simultaneously throwing innocent people to the lions, literally, to protect his own reputation.

Commodus: Gladiator ego over emperor duty

Commodus wanted to be a gladiator, not an emperor. He actually fought in the arena, reportedly winning hundreds of staged bouts against opponents who knew better than to hurt the boss.

His theatrical self-image became more important than running an empire.

Rome’s government deteriorated under his rule. Commodus preferred spectacle to statecraft, and his advisors basically ran things while he played dress-up.

His megalomania grew so extreme he renamed Rome after himself.

Was this cowardice? Commodus avoided the hard work of governing by hiding behind entertainment and self-glorification.

He chose the easy path of manufactured heroism over actual leadership.

His assassination in 192 surprised nobody. A conspiracy of fed-up officials arranged for a wrestler to strangle him in his bath.

Commodus’s reign shows how someone can be simultaneously reckless and cowardly. Fighting rigged gladiator matches while avoiding real responsibility takes a special kind of weakness.

He wanted glory without danger, fame without duty. That’s not courage.

That’s just ego with a costume.

Adolf Eichmann: The ‘just following orders’ defense

Eichmann sat in his glass booth in Jerusalem in 1961, calmly explaining that he was just following orders. He organized Holocaust logistics with bureaucratic efficiency, sending millions to their deaths with paperwork and train schedules.

His defense became infamous as the ultimate example of moral cowardice. Eichmann claimed he had no choice, that he was merely a cog in the machine.

But choosing not to choose is still a choice.

Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “banality of evil” after watching his trial. Eichmann wasn’t a monster in appearance.

He was a middle-aged bureaucrat who refused to accept responsibility for monstrous actions.

That’s the cowardice that still chills people today. Eichmann had agency.

He could have resisted, sabotaged, or at minimum refused promotion. Instead, he advanced his career by advancing genocide.

His “just following orders” defense wasn’t an explanation. It was an admission that he valued his own comfort over millions of lives.

That’s not just cowardice. That’s choosing cowardice as a life strategy.

Vidkun Quisling: Pragmatist or pure collaborator?

Quisling’s name literally became a word for traitor. As Norway’s Minister President under Nazi occupation, he collaborated so enthusiastically that his surname entered multiple languages as a synonym for treasonous collaboration.

He claimed he was being pragmatic, protecting Norway from worse treatment by cooperating with Germany. His defenders argued he was trying to preserve Norwegian institutions under impossible circumstances.

Nobody bought it then. Nobody buys it now.

The evidence suggests pure opportunism. Quisling saw German victory as inevitable and positioned himself accordingly.

He wasn’t protecting Norway. He was protecting himself and grabbing power.

Norway executed him for treason in October 1945. His trial revealed the depth of his collaboration and his complete lack of genuine patriotism.

Quisling’s story illustrates how cowardly opportunism can disguise itself as pragmatism. He made the calculation that saving his own skin mattered more than his country’s freedom.

That’s not caution. That’s cowardice wrapped in political justification.

Louis XVI: Indecision and the night he ran

Louis couldn’t make up his mind. As the French Revolution gathered momentum, he vacillated between reform and resistance, satisfying nobody.

Then came the night of June 20, 1791, when he tried to flee France with his family.

The Flight to Varennes failed spectacularly. Recognized despite his disguise, Louis was arrested and brought back to Paris in humiliation.

Revolutionary leaders now knew their king had tried to abandon them and seek foreign military support.

Was this cowardice or a desperate father trying to save his family? Both, probably.

Louis faced impossible choices. Staying meant possible death.

Fleeing meant abandoning his kingdom. He chose flight and bungled it.

His indecision proved fatal. Had Louis committed firmly to either reform or resistance earlier, he might have survived.

Instead, his hesitation and failed escape convinced revolutionaries he couldn’t be trusted. By 1793, he’d lost his head.

Louis’s tragedy shows how indecision can be its own form of cowardice, and sometimes the cautious middle path leads straight to the guillotine.

Wilhelm II: The Kaiser who lost control of the ending

Germany was collapsing in November 1918. Revolution spread through cities, sailors mutinied, and Wilhelm’s government crumbled.

Someone announced his abdication before he’d even agreed to it. Soon he was on a train to exile in the Netherlands.

Critics called it fleeing responsibility. As Kaiser, Wilhelm bore significant blame for World War I’s outbreak and Germany’s defeat.

When the bill came due, he ran rather than face the consequences.

His defenders argue he left to prevent civil war and bloodshed. If Wilhelm had stayed and fought to keep his throne, Germany might have descended into worse chaos.

His departure allowed the new government to negotiate peace.

But exile in comfortable Dutch estates doesn’t look like noble self-sacrifice. Wilhelm lived comfortably until 1941, never really accepting responsibility for his role in the catastrophe.

Was leaving Germany cowardice or wise caution? Perhaps it was simply a recognition that he’d lost control and couldn’t fix what he’d broken.

Sometimes knowing when to leave is wisdom. Sometimes it’s just running away.

Henry VI: A gentle king in a brutal era

Henry VI was too kind for his job. Pious, gentle, and prone to mental breakdowns, he inherited the throne at nine months old and never really grew into it.

England needed a warrior king. It got a man who preferred prayer to politics.

His weakness helped trigger the Wars of the Roses. Nobles fought over power while Henry suffered mental collapses.

His queen, Margaret of Anjou, proved far more politically capable than he ever was, which didn’t help his reputation.

Was Henry a coward? Not exactly.

He simply lacked the personality, skills, and possibly mental health needed for medieval kingship. Calling him cowardly seems unfair when he was fundamentally incapable of the role.

His reign ended with deposition, brief restoration, then murder in the Tower of London in 1471. Henry’s tragedy illustrates how someone can fail catastrophically without being a coward.

He was profoundly unsuited to his era’s brutal demands. That’s not cowardice.

That’s just being the wrong person in the wrong job at the worst possible time.

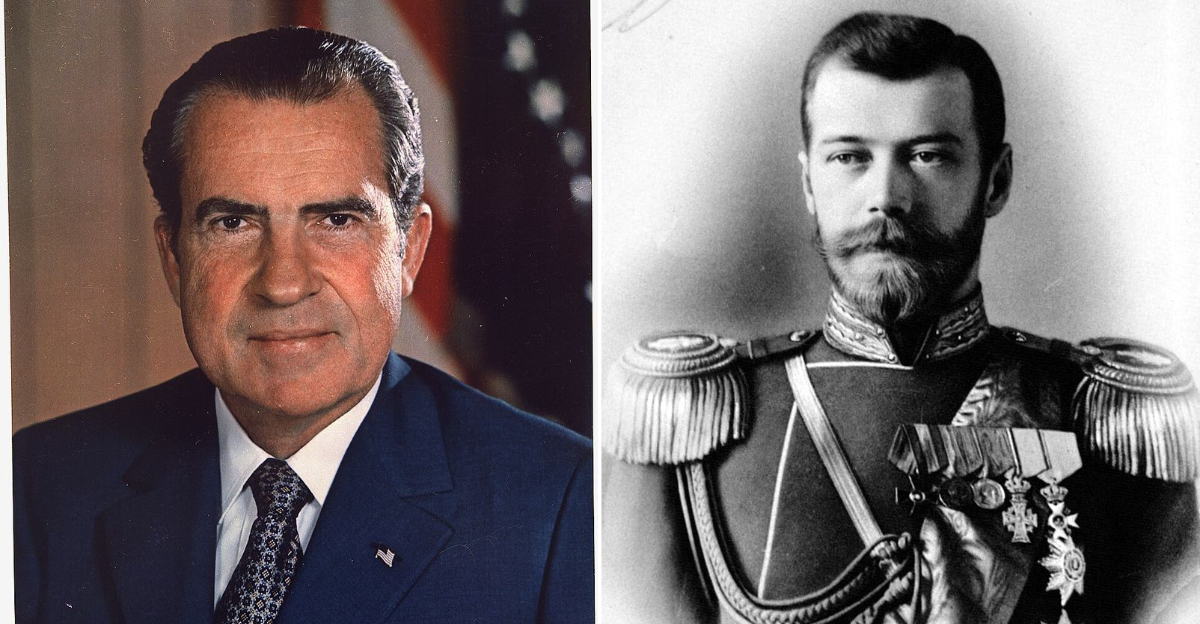

Nicholas II: Fatalistic delay as the empire collapsed

Nicholas clung to autocracy as Russia burned. Through 1917, as revolution spread and his army dissolved, the Tsar seemed paralyzed.

He’d already made catastrophic decisions by taking personal command during World War I, leaving his government in Alexandra’s and Rasputin’s hands.

When the crisis finally came, Nicholas tried to hold everything together through sheer force of will and divine right. It didn’t work.

His generals and political leaders turned against him. He abdicated in March 1917, ending three centuries of Romanov rule.

Was this cowardice? Nicholas’s abdication came too late to save anything, including himself and his family.

The Bolsheviks would murder them all in July 1918. He’d failed to reform when reform might have worked.

Some historians see fatalistic paralysis rather than cowardice. Nicholas believed God had chosen him to rule, so yielding seemed impossible until it became inevitable.

His tragedy was believing too long that divine providence would save him. That’s not quite cowardice.

It’s something stranger: religious certainty meeting historical forces it couldn’t comprehend or control.

Richard Nixon: Resigned, coward’s exit or country-first move?

Nixon waved goodbye on August 9, 1974, boarding the helicopter that would take him away from the White House forever. Watergate had destroyed his presidency.

Impeachment was coming. He quit rather than face it.

Critics saw pure cowardice. Nixon had lied, covered up crimes, and abused presidential power.

When caught, he ran rather than face judgment. His resignation let him escape with a pardon instead of possible prison.

Defenders argue resignation actually helped the country. A lengthy impeachment trial would have paralyzed government for months.

Nixon’s departure, however disgraceful, let the nation move forward and heal.

Both arguments have merit, which is why the debate continues. Nixon’s resignation was simultaneously self-serving and pragmatic.

He avoided humiliation while sparing the country further trauma. That’s not pure cowardice, but it’s not exactly courage either.

It’s the kind of calculated exit that leaves everyone arguing about whether it was the right move or just the expedient one. Maybe that ambiguity is Nixon’s most fitting legacy.

Edward VIII: Love over the crown

Edward chose Wallis. In December 1936, facing opposition from government, church, and family, he abdicated the British throne to marry the twice-divorced American woman he loved.

The crisis shocked the empire.

Many saw it as weakness. Edward had been king for less than a year.

He abandoned duty for personal desire, dodging the responsibilities his birth had given him. His father George V had supposedly predicted Edward would ruin himself.

Others saw unexpected integrity. Edward refused to live a lie or enter a loveless marriage for appearances.

He made an honest choice, accepting the consequences rather than hiding behind royal hypocrisy.

The truth probably lies somewhere between. Edward wasn’t a particularly good king in his brief reign.

He had Nazi sympathies that would have caused major problems. His abdication might have saved Britain from a terrible wartime monarch.

Was choosing love over duty cowardice? Or was it recognizing he didn’t want the job badly enough to give up happiness?

Sometimes walking away isn’t running away. Sometimes it’s just being honest.

James Buchanan: Inaction before the explosion

Buchanan watched helplessly as the Union crumbled. After Lincoln’s election in November 1860, Southern states began seceding.

As sitting president, Buchanan had months to act. He did almost nothing.

His inaction is often called cowardice. Buchanan believed he lacked constitutional authority to stop secession by force, but also believed secession was illegal.

This logical pretzel paralyzed him. He waited, hoped, and prayed the crisis would resolve itself.

It didn’t. By the time Buchanan left office in March 1861, seven states had seceded and formed the Confederacy.

The Civil War was weeks away. His failure to act decisively remains one of history’s most criticized presidential performances.

Was Buchanan a coward or just constitutionally constrained? Both, probably.

He hid behind legal arguments because he feared the consequences of action. His caution helped enable catastrophe.

Sometimes doing nothing is the most cowardly choice of all. Buchanan’s presidency proves that inaction in the face of crisis isn’t neutrality.

It’s choosing to let disaster happen rather than risk trying to stop it.