Penguins in Antarctica are shifting their breeding schedules earlier by about two weeks in just a decade, and scientists are watching closely. This rapid change is tied to warming temperatures, melting ice, and shifts in the food web that penguins depend on.

Understanding why this is happening helps us see how climate change is reshaping life at the bottom of the world.

1. The shift is measurable: about two weeks earlier in ~10 years

Scientists tracking three Antarctic penguin species have recorded something remarkable. Over the past decade, these birds have started their breeding cycles roughly 14 days sooner than before.

That might sound small, but for vertebrates, it represents an exceptionally rapid pace of change.

Researchers use long-term data to spot these patterns. When animals change their life cycle timing this fast, it signals that their environment is shifting in powerful ways.

Penguins are responding to cues around them, and those cues are arriving earlier each year.

2. The colonies themselves are warming quickly

Between 2012 and 2022, temperatures at penguin breeding grounds rose by about 3°C, or 5.4°F. That is a dramatic jump in just ten years.

The Antarctic Peninsula has warmed nearly 3°C since 1950, though not all parts of the continent are changing at the same rate.

Warmer air means less ice, earlier snowmelt, and different weather patterns. Penguins evolved to breed in harsh, cold conditions.

When those conditions soften and shift, the birds must adjust or risk falling out of sync with their environment.

3. Earlier snow/ice retreat = earlier access to nesting real estate

Penguins need bare ground or stable ice to build nests, form pairs, and lay eggs. Snow-covered terrain is useless for nesting.

When spring warmth arrives earlier, snow melts sooner, and nesting spots open up ahead of schedule.

This early access is like a green light for breeding. Penguins are hardwired to respond to environmental signals.

If the land is ready earlier, they begin earlier. The whole reproductive season slides forward, following the retreat of snow and ice.

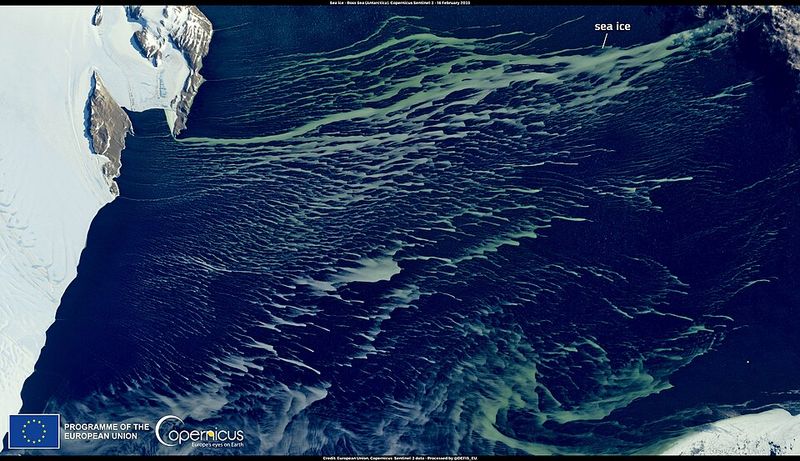

4. The food calendar shifts too – starting at the bottom of the food chain

Phytoplankton blooms kick off the Antarctic food web each spring. These tiny organisms feed krill, and krill feed penguins.

When sea ice retreats earlier, phytoplankton blooms can start earlier too. That ripple effect moves up the food chain.

Penguins are trying to time chick-rearing with peak food availability. If krill abundance peaks earlier, penguins need to breed earlier so their hungry chicks match that window.

Falling out of sync means chicks go hungry, and survival rates drop.

5. Breeding is a high-stakes synchronization game

Timing is everything for penguins. They must lay eggs, incubate them, and raise chicks so that peak chick hunger lines up with peak food in the ocean.

Miss that window, and chicks starve. Nail it, and the colony thrives.

Climate change complicates this game. If the ecosystem shifts faster than penguins can adapt, the match breaks down.

Even small mismatches can mean lower chick survival. Penguins are racing to keep up with a moving target they did not create.

6. Gentoo penguins look like the fast adapters

Among the three species studied, gentoo penguins are shifting their breeding schedules earlier faster than the others. They also have more varied diets, eating different types of prey depending on what is available.

That flexibility gives them an edge.

When the environment changes quickly, generalists often do better than specialists. Gentoos can switch prey, adjust timing, and explore new feeding areas.

In a rapidly warming Antarctica, being adaptable might be the key to survival.

7. Adélie and chinstrap penguins are more food-specialized

Adélie and chinstrap penguins depend heavily on krill for food. Unlike gentoos, they are not as flexible in what they eat.

When krill populations shift in timing, location, or abundance, these penguins feel the impact more sharply.

Specialization works well in stable environments. But when conditions change fast, specialists struggle.

If krill blooms arrive at a different time or place, Adélie and chinstrap penguins may not be able to adjust quickly enough to keep their chicks fed and healthy.

8. The hidden problem: earlier breeding creates new overlap

Historically, different penguin species bred at slightly different times. This staggered schedule reduced direct competition for nesting sites and food.

But when one species shifts earlier faster than the others, breeding windows start to overlap.

Overlap means more penguins are foraging hard at the same time. More birds chasing the same food in the same waters can strain resources.

What used to be a well-spaced system is now becoming crowded and competitive.

9. When overlap happens, competition can get physical and territorial

Competition is not just about food. Researchers have observed gentoo penguins taking over nesting spaces that used to belong to other species.

When breeding schedules collide, so do the birds themselves. Territory disputes can turn aggressive.

Nesting real estate is limited in Antarctica. Prime spots with good access to the ocean and protection from wind are valuable.

As timing shifts, species that were once separated by weeks are now jostling for the same ground at the same time.

10. Earlier isn’t always safer: weather can still snap back

Even though average temperatures are rising, Antarctica can still deliver brutal late-season storms, deep freezes, and heavy snow. Breeding earlier can expose eggs and vulnerable chicks to conditions that have not yet become reliably mild or springlike.

Penguins are tough, but their chicks are fragile. A sudden cold snap or blizzard can wipe out nests.

Earlier breeding is a gamble. In some years it pays off, but in others, unpredictable weather can reduce breeding success dramatically.

11. Wet nests become a bigger risk as conditions soften

Warming brings more meltwater and rain-on-snow events. Nests can flood, chicks can get soaked, and survival rates drop.

Penguins are incredible swimmers, but chicks sitting still in wet, cold conditions are extremely vulnerable to hypothermia.

Dry nests are essential for chick survival. When snow melts unpredictably or rain falls instead of snow, the ground becomes slushy and unstable.

Wet feathers lose their insulating power, and chicks can die from exposure even if temperatures are not freezing.

12. Human pressure can collide with the same timing window

Ecological shifts can coincide with increased or earlier-season human activity. Fishing boats, for example, may now overlap more with penguin foraging areas during chick-rearing.

This can tighten food availability when penguins need it most.

Humans and penguins are both responding to the same environmental signals. Warmer, earlier springs mean earlier fishing seasons.

When commercial fishing targets krill or fish in the same waters penguins depend on, competition intensifies, and penguin chicks may suffer.

13. The big-picture trend: climate change creates winners and losers

Climate change does not affect all species equally. Some penguins, like gentoos, may adapt and even thrive in new conditions.

Others, like Adélie and chinstrap penguins, may struggle and decline. This is not a simple story of adaptation solving every problem.

Generalists often benefit from change, while specialists suffer. Ecosystems are reshuffling, and not all species will come out ahead.

Understanding who wins and who loses helps scientists predict the future of Antarctic wildlife and guide conservation efforts.

14. How scientists know all this: cameras + citizen science at scale

Large-scale time-lapse monitoring and citizen science have made this research possible. Cameras placed at penguin colonies capture millions of images over years.

Volunteers around the world help tag and analyze those photos, turning raw images into usable ecological data.

Without this technology and public participation, tracking subtle shifts in breeding timing would be nearly impossible. Citizen scientists are helping researchers spot patterns, measure change, and understand how quickly Antarctica is transforming.

It is a powerful example of collaboration in action.