Every generation has its quirks, but Baby Boomers might hold the record for the most eye-roll-inducing favorites. From chunky gadgets to paper-based everything, the tools and traditions Boomers swear by can seem like artifacts from another planet to Gen Z.

Scroll through any comment section and you will find the generational debate alive and well. Here are 14 Boomer classics that have Gen Z reaching for their invisible patience reserves.

Rotary-Dial Telephones

Picking up a rotary phone was basically signing up for a finger workout you never asked for. Each digit required you to hook your finger into a little hole, drag it all the way around, and wait for it to click back before dialing the next number.

Miss one digit? Start completely over.

No shortcuts, no autocomplete, just pure patience.

I tried using one at an antique shop once, and by the time I dialed four digits, I had already reconsidered the entire phone call. Gen Z, who can voice-dial someone mid-snack, cannot fathom why anyone thought this was a reasonable communication system.

The rotary phone was invented in the late 1800s and dominated homes for nearly a century. That is an impressive run for something that basically punished you for having a phone number with a lot of nines in it.

Boomers remember it fondly. Gen Z sees it as a device specifically engineered to test whether you really wanted to make that call in the first place.

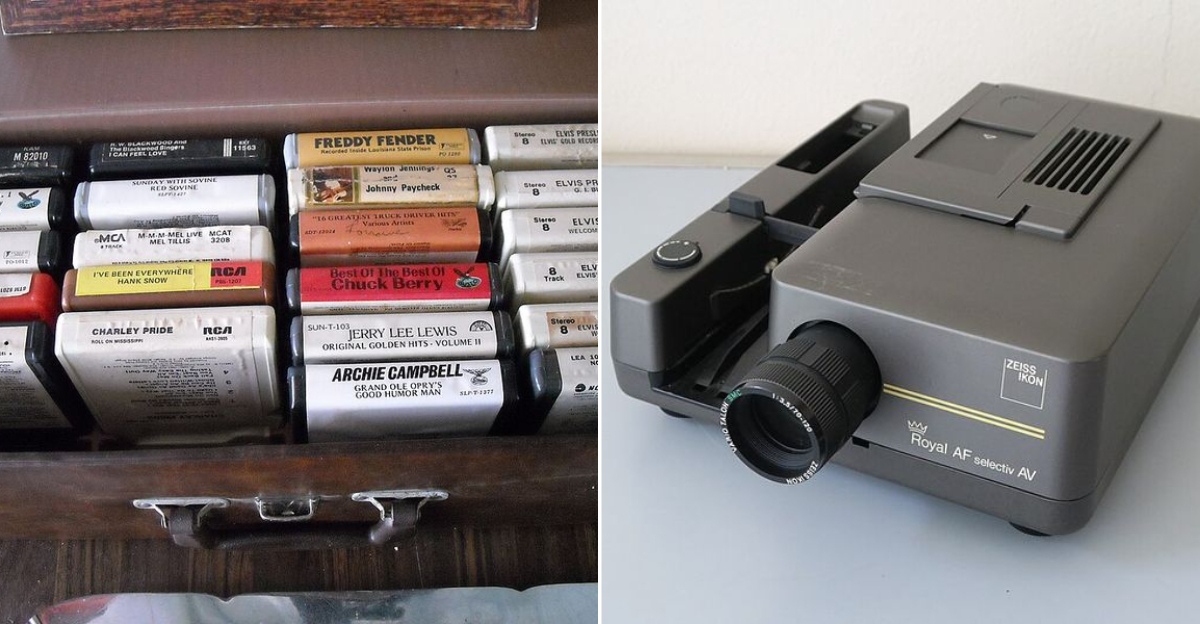

8-Track Tapes

Nothing killed the vibe quite like an 8-track tape cutting out mid-chorus and switching to the next program track. You would be deep in a song, feeling every note, and then click, silence, and you were suddenly halfway through a completely different track.

The machine did not care about your emotional journey.

These chunky plastic cartridges were the streaming service of the 1970s, except they skipped randomly, required occasional physical persuasion, and sometimes needed a folded piece of cardboard jammed underneath to play correctly. That last part is absolutely true and not a joke.

Boomers who grew up with 8-tracks remember them as a genuine step forward in portable music. Gen Z, raised on platforms that let you skip, shuffle, and replay any song instantly, simply cannot process the concept of music being this high-maintenance.

The format was discontinued by the early 1980s, but its legacy lives on as the ultimate example of technology that was impressive for about fifteen minutes before everyone moved on and quietly pretended it never happened.

Film Cameras and Darkrooms

You got 24 shots on a roll of film, and every single one felt like a small gamble. Blink at the wrong moment, hold the camera slightly crooked, or forget the lens cap, and you would not find out until days later when the prints came back from the pharmacy.

It was photography with built-in suspense.

Darkrooms were their own adventure: red lights, chemical smells, and the slow magic of watching an image appear in a tray of developer fluid. I once visited a school darkroom and knocked over a tray of fixer solution, which smelled like sulfur had a bad week.

Respect to anyone who did this regularly.

Gen Z shoots 40 photos in ten seconds, picks the best one with a filter already applied, and posts it before the moment has even fully ended. The idea of waiting days to see whether anyone had their eyes open in a group shot is genuinely baffling to them.

Film photography has made a comeback among younger creatives, but mostly for the aesthetic, not because anyone misses the chemical smell or the suspense of ruined vacation photos.

Slide Projectors for Family Photos

The slide projector night was a whole event, and attendance was not optional. Someone would dim the lights, set up the screen, load the carousel, and then proceed to narrate 73 vacation slides with the enthusiasm of a National Geographic documentary host.

Every single photo got commentary.

There was no fast-forward. No skipping to the good ones.

Just click, narrate, click, narrate, while everyone sat politely and pretended to be fascinated by a slightly blurry photo of a highway rest stop taken somewhere in 1971. The projector bulb overheating mid-show was sometimes a welcome interruption.

Gen Z shares vacation photos instantly on stories that disappear in 24 hours, which honestly feels like the opposite extreme. One format forces you to sit through everything; the other barely gives you time to react before it vanishes.

Slide projectors were actually a genuine innovation when they launched, turning home photography into a shared experience. But shared experiences work better when the audience has a choice.

Boomers call it togetherness. Gen Z calls it a very slow, very warm evening with no escape route.

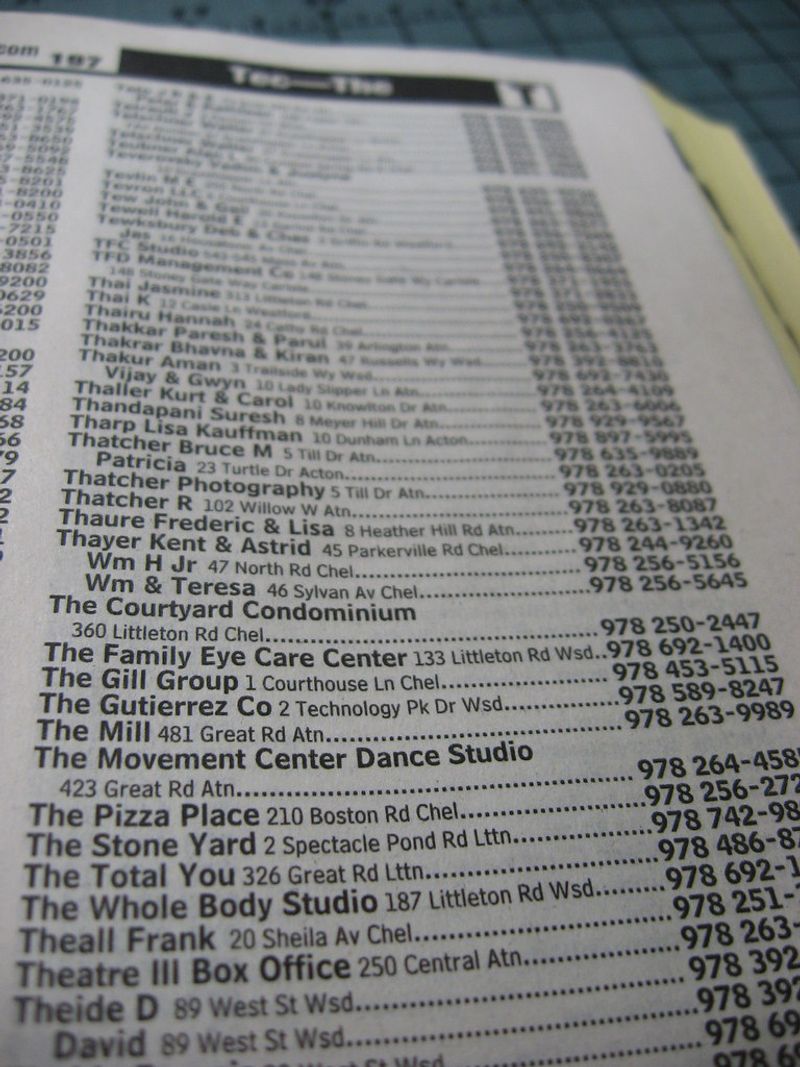

Printed Phone Books

Every year, a massive book containing the names, addresses, and phone numbers of everyone in your city would appear on your doorstep, completely uninvited. Nobody asked for it.

It just arrived. And for some reason, this was considered a public service rather than a privacy nightmare.

Boomers used phone books constantly: to find businesses, look up neighbors, and occasionally prop up a wobbly table leg. The Yellow Pages section for businesses was genuinely useful before search engines existed.

The sheer weight of a big-city directory was impressive in a very specific, paper-based way.

Gen Z’s reaction to learning that everyone’s home address was just printed in a book and delivered to strangers is somewhere between disbelief and mild horror. “So you published everyone’s personal information and called it normal?” is not an unreasonable response. Phone books were officially discontinued in most U.S. markets by the mid-2010s, though some rural directories still exist.

Boomers remember them as essential tools. Gen Z sees them as the world’s least secure database, printed in bulk and handed out for free to absolutely anyone who opened their front door.

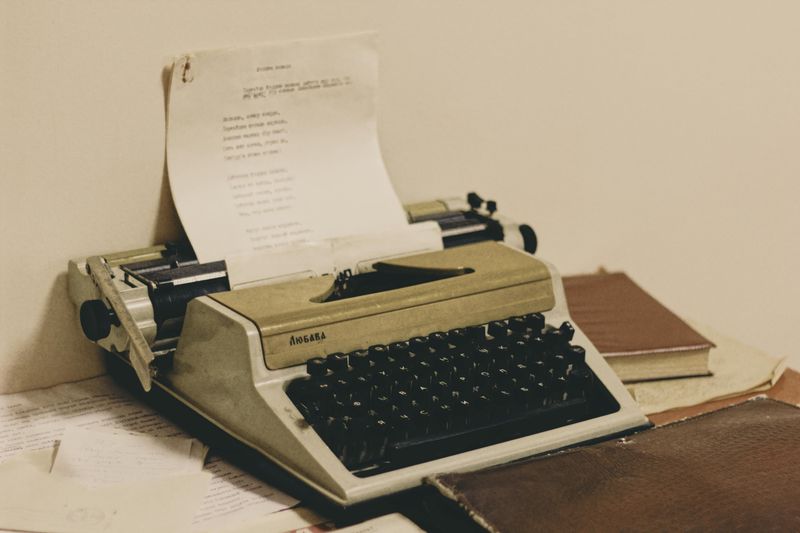

Typewriters

Typewriters look incredible in photos. That is genuinely true.

There is something about the mechanical design, the round keys, and the satisfying clack that photographs beautifully and makes any desk look like it belongs to a serious intellectual. The reality of actually using one is a completely different story.

Every keystroke required real force. One typo meant either using correction fluid, retyping the entire page, or just accepting that the document now had a visible mistake forever.

The backspace key existed but did absolutely nothing useful. It just moved the carriage.

The typo stayed.

Gen Z loves the typewriter aesthetic on social media. Plenty of younger people actually own them for journaling or creative writing, drawn in by the tactile experience and the very cool clacking sound.

But the moment they realize that fixing a mistake involves liquid paper, waiting for it to dry, and hoping the correction lines up properly, the romance fades quickly. Boomers typed entire novels and business reports this way without complaint.

Gen Z respects that dedication while also being very relieved that word processors exist and that Ctrl+Z is always just two keystrokes away.

Payphones

Paying actual coins to make a phone call from a glass box on a public street corner, while strangers walk by and hear everything, is a concept so foreign to Gen Z that it practically qualifies as historical fiction. And yet, for decades, payphones were the only option when you were out and needed to reach someone.

The logistics alone were wild. You needed exact change, the number memorized, and enough confidence to talk through whatever was happening in your life while a stranger waited behind you, jangling their coins impatiently.

Privacy was not part of the payphone experience.

At their peak in the 1990s, there were over 2 million payphones in the United States. Today, that number has dropped to a few thousand, mostly in places with limited cell coverage.

New York City officially removed its last traditional payphone in 2022, replacing them with Wi-Fi kiosks. Boomers remember payphones as lifelines.

Gen Z cannot process the idea of not having a personal communication device at all times, let alone one that required quarters and offered zero privacy. The payphone era ended not with a bang but with a very quiet coin slot going permanently silent.

Drive-In Movie Theaters

Drive-in theaters have a genuinely great reputation, and a lot of that reputation is based on how they look in photos rather than how they actually work. The idea of watching a movie from your car under the stars sounds romantic until you are forty minutes into tuning your FM radio to the right station and someone three cars over has their headlights on full beam.

Parking strategy was a real skill. Get there too early and you wait forever.

Get there too late and you end up at a bad angle, watching the movie through someone else’s rear window. Also, the speaker posts that used to hang on car windows rattled and had notoriously questionable audio quality.

Here is something worth knowing: drive-ins are not actually gone. The United States still has around 300 operating drive-in theaters, with active owner associations and directories keeping the format alive.

Some have upgraded to digital projection and app-based audio, which solves the FM radio problem entirely. Gen Z often loves the drive-in experience once they actually try it.

The eye-rolling is mostly at the logistics, not the concept itself. The concept, it turns out, still holds up pretty well on a warm summer night.

Mimeograph Machines

If you walked into a classroom in the 1960s or 70s and smelled something between fresh ink and a chemistry experiment gone sideways, that was the mimeograph machine announcing its presence. Teachers would hand out worksheets still warm from the drum, printed in a distinctive purple ink that smelled unlike anything before or since.

The mimeograph worked by forcing ink through a stencil onto paper, one sheet at a time. The copies were never perfectly crisp.

Text sometimes blurred at the edges, and the purple color faded quickly. By modern standards, it looked like something printed by a machine that was doing its best under difficult circumstances.

Gen Z, raised on laser printers that produce razor-sharp copies in seconds, genuinely cannot process the idea of teachers accepting these slightly smudged, faintly purple worksheets as official educational materials. The smell, apparently, was so distinctive that many Boomers remember it with surprising fondness, which says a lot about how powerfully scent links to memory.

The mimeograph was replaced by photocopiers in most schools by the 1980s. Its legacy is mostly the smell, the purple ink, and the very specific nostalgia of receiving a worksheet that was still warm when it landed on your desk.

TV Rabbit Ears Antennas

The rabbit ears antenna system required a level of household cooperation that no piece of modern technology has ever demanded. One person would stand next to the TV, moving the antenna in tiny increments, while someone across the room yelled instructions based on whether the static improved or got worse.

It was a team sport nobody signed up for.

The magic position, once found, was sacred. Nobody moved.

Nobody breathed too hard near the TV. If someone accidentally bumped the antenna on their way to the kitchen, they returned to genuine social consequences.

The signal was fragile, the patience required was significant, and the picture quality on a good day was still pretty questionable.

Here is a fact worth knowing: over-the-air television with antennas is still a real thing in 2024, just digital now. Modern antennas pick up free HD broadcasts from local stations, and millions of households use them as a legitimate alternative to cable.

Gen Z cutting the cord has actually brought the antenna back in a sleek, flat, modern form. The rabbit ears themselves are gone, replaced by something that looks like a small black rectangle.

Same concept, zero yelling required. Boomers did it the hard way.

Gen Z gets to do it the easy way and call it a money-saving hack.

Milk Delivery in Glass Bottles

Every morning, a milkman would quietly leave glass bottles of fresh milk on your doorstep before you woke up. No app, no tracking number, no delivery window between 8am and 8pm.

Just cold bottles waiting patiently on the porch when you opened the door.

Gen Z’s reaction to this is genuinely split. Half find it charming in a wholesome, small-town-America kind of way.

The other half immediately point out that a stranger was regularly accessing your front porch before dawn and leaving perishable dairy products outside in all weather conditions. Both reactions are completely valid.

The important thing to know is that milk delivery in glass bottles is not just history. Several dairies and services still offer home delivery in reusable glass bottles today, marketed as an eco-friendly and nostalgic alternative to plastic jugs.

Companies like Oberweis and various local creameries have kept the tradition alive, and the model has seen renewed interest as sustainability becomes a bigger consumer priority. Boomers remember the milkman as a neighborhood fixture.

Gen Z, once they learn the glass bottle delivery model still exists, sometimes actually signs up for it, which might be the most unexpected generational plot twist on this entire list.

Jukeboxes in Diners and Bars

Few things in a 1950s diner hit harder than sliding a coin into a jukebox and watching it mechanically select your record. The whole machine was a performance: the arm moving, the vinyl dropping, the needle finding the groove.

Choosing a song felt like an event rather than a tap on a screen.

Boomers who grew up with jukeboxes in diners and bars remember the social ritual of it. You walked up, flipped through the song cards, made your selection, and then everyone in the room heard what you picked.

Music choice was public and slightly vulnerable, which made it more meaningful somehow.

Gen Z tends to clown the concept until they find out that modern venues still use jukebox networks, just digital ones. TouchTunes, one of the biggest digital jukebox platforms, operates in over 65,000 bars and restaurants across North America.

Patrons control song selection through a smartphone app, sometimes even paying to skip other people’s choices. The social dynamic is identical to the original jukebox experience, just without the mechanical arm and with significantly more passive-aggressive skipping.

The jukebox never died. It just got a software update and a monthly subscription model, which honestly feels very on-brand for this era.

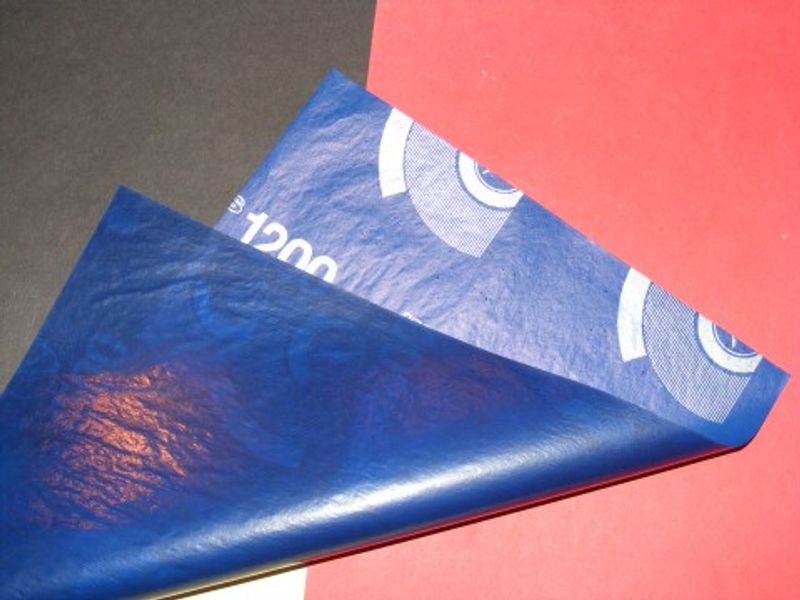

Carbon Paper

Making a duplicate document in the pre-photocopier era required careful preparation: one sheet of paper on top, one sheet of carbon paper in the middle, one blank sheet underneath, all aligned perfectly, then written or typed with enough pressure to transfer the ink through. One wrong move and your copy had a smudge the size of a thumb in the middle of the most important line.

Carbon paper was standard office equipment for decades. Receipts, contracts, and invoices all used it.

The carbon copy became so embedded in professional culture that we still use the abbreviation CC in emails today, even though almost nobody under 30 knows what it originally stood for.

Gen Z’s entire concept of duplication is Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V. The idea of making a copy being a physical, multi-layered, pressure-dependent process is genuinely hard to wrap a modern brain around.

Carbon paper smudged easily, the copies were always slightly lighter than the original, and the blue or black transfer ink had a habit of ending up on your hands, your sleeves, and occasionally your face. Boomers used it daily without complaint.

Gen Z can appreciate the ingenuity while also being profoundly grateful that duplicating a document now takes approximately zero physical effort.

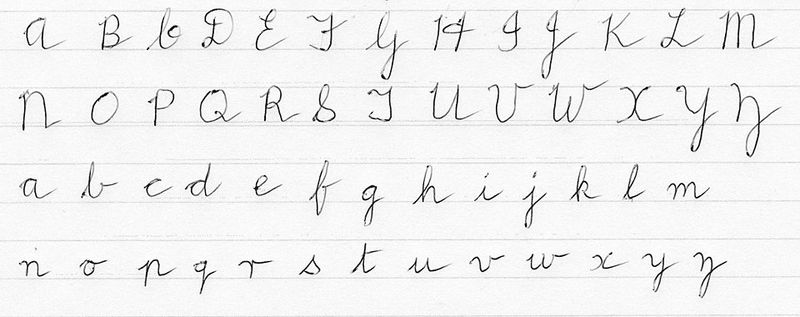

Cursive Handwriting Classes

Cursive handwriting was treated as a core life skill for generations. Schools dedicated real classroom time to teaching the loops, the connections, the slant, and the flow of joined-up letters.

Getting your cursive right felt like graduating from childhood printing into something more sophisticated and grown-up.

Boomers who learned cursive remember the satisfaction of a well-formed page of connected letters. There was a genuine craft to it.

Some people developed beautiful, distinctive handwriting that felt personal and expressive in a way that typed text never quite matches. Signatures especially carried a sense of identity and authority that a printed name just does not replicate.

Gen Z was mostly taught cursive too, often with the same promises that it would be essential later in life. Then the world switched almost entirely to typing, texting, and voice notes, and the cursive lessons faded into a skill used primarily for signing documents and occasionally reading old letters from grandparents.

Many U.S. states have actually brought cursive back into school curricula in recent years, partly because research suggests handwriting supports memory and learning. Whether that changes Gen Z’s relationship with it remains to be seen.

For now, most of them can technically write in cursive. They just choose not to, and honestly, the keyboard has made a pretty compelling case for itself.