Some places didn’t just exist – they defined eras. They sparked obsessions, anchored skylines, and became the backdrop for memories millions of people thought would always be there.

And then, suddenly or slowly, they were gone. What’s left behind isn’t just empty space.

It’s debate, regret, nostalgia – and hard lessons about what we choose to protect. In this list, you’ll discover the remarkable sites that once shaped culture and architecture, why they vanished, what (if anything) still stands today, and how their loss changed the way we think about preservation.

Let’s revisit what disappeared – and what it taught us.

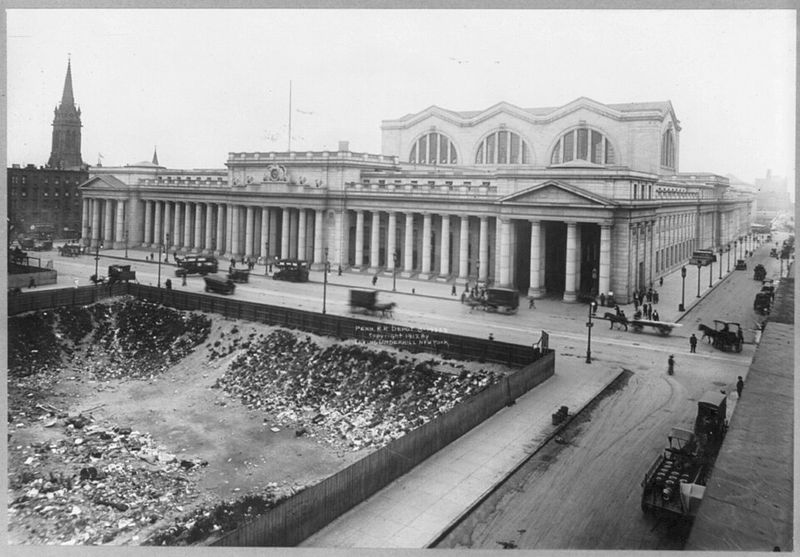

1. The Original Penn Station (New York City, USA)

The original Pennsylvania Station in New York City opened in 1910, a triumph of Beaux-Arts design by McKim, Mead and White. Its vast train shed and monumental concourse combined steel, glass, and classical ornament, creating a cathedral of transit.

Demolished in 1963, it sparked a national reckoning about preservation.

You cannot visit it today because the structure was completely razed, replaced by a subterranean complex beneath Madison Square Garden. What remains are archival photographs, fragments preserved at museums, and a sharpened public memory of what was lost.

That loss directly influenced creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

When you walk through present-day Penn Station, it is hard to imagine the former light-filled vaults and dignified procession of space. Efforts like Moynihan Train Hall nod to the spirit of the original, but they are not the same building.

The disappearance of old Penn Station still guides debates about development, heritage, and civic pride.

2. The Old World Trade Center Windows on the World (NYC, USA)

Windows on the World sat atop the North Tower of the World Trade Center, offering sweeping views of New York Harbor and beyond. The restaurant opened in 1976 and became a destination for fine dining, business gatherings, and special occasions.

Its skyline vistas were unmatched, a literal window onto the city.

You cannot visit because it was destroyed during the September 11, 2001 attacks. The space and the tower are gone, and with them the atmosphere that made the restaurant iconic.

Memorials and the rebuilt site honor those lost, but the original experience cannot be recreated.

If you are curious about its legacy, menus, wine lists, and staff stories survive in books and archives. The One World Observatory offers a different vantage point nearby, yet history sets the two apart.

Remembering Windows on the World is inseparable from remembering the people and the moment it represented.

3. The Berlin Wall (Germany)

The Berlin Wall divided East and West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, a stark symbol of the Cold War. Concrete segments, guard towers, and the death strip enforced separation with unforgiving efficiency.

Street art and protest slogans covered the western face, while the eastern side remained bare and heavily policed.

You cannot visit the wall as it once stood because most of it was dismantled after 1989. Today only segments remain, like those at the East Side Gallery and memorial sites.

These fragments document the structure, but the original barrier no longer exists in its full, contiguous form.

When you walk along Bernauer Strasse, interpretive exhibits explain escapes, surveillance, and reunification. The city reclaimed former borderlands with parks and paths, transforming a place of division into shared civic space.

What you see now is history contextualized, not the oppressive system that once defined daily life.

4. The Crystal Palace (London, UK)

The Crystal Palace, built for the Great Exhibition of 1851, showcased Victorian engineering with iron ribs and an ocean of glass. Designed by Joseph Paxton, it housed innovations, exotic plants, and global displays.

After the exhibition, it was relocated to Sydenham and became a cultural landmark.

You cannot visit the original structure because it was destroyed by fire in 1936. Today, Crystal Palace Park preserves the site’s memory through terraces, sculptures, and the famous dinosaur models.

The hall’s volume and shimmering transparency exist only in drawings, photographs, and written accounts.

When you wander the park, it takes imagination to picture the colossal nave and barrel vaults. Architectural historians credit the building with advancing modular construction and inspiring later glasshouses.

Its loss underscores both the brilliance and fragility of 19th century materials and urban spectacle.

5. The Buddhas of Bamiyan (Afghanistan)

The Buddhas of Bamiyan were monumental statues carved into Afghanistan’s Bamiyan cliffs, dating to the 6th century. They represented a fusion of Hellenistic and Buddhist art along the Silk Road.

For centuries, travelers described their serene faces and draped robes soaring above the valley.

You cannot visit the statues because they were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. The empty niches remain, along with fragments and archaeological efforts to document the site.

Conservation work now focuses on stabilization, research, and respectful presentation of absence.

If you visit the valley, guides explain the sculptures’ dimensions, pigments, and the caves that once housed murals. International debates continue over reconstruction versus preserving the void as testimony.

Standing before the vast hollows, you confront both cultural loss and the resilience of memory.

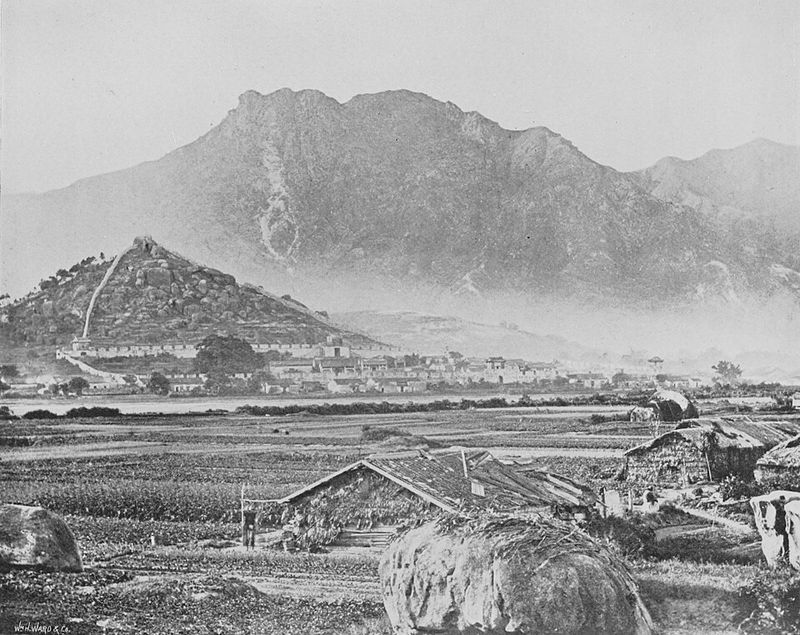

6. The Old Kowloon Walled City (Hong Kong)

Kowloon Walled City was once the most densely populated place on Earth, a self-built maze of interlocking apartments and workshops. Residents stacked structures without formal planning, creating a vertical warren of corridors and rooftops.

Despite harsh conditions, it fostered tight communities and resourceful micro economies.

You cannot visit because the enclave was demolished in 1993. In its place stands Kowloon Walled City Park, designed with classical Chinese garden elements and historical markers.

The park interprets the site’s Qing era origins and the later unregulated urbanism.

If you seek traces, museums display models, photographs, and oral histories. Video games and films often reference its claustrophobic aesthetics, but they are stylized echoes.

The lived reality of cramped alleys, improvised plumbing, and pervasive neon belongs to the past.

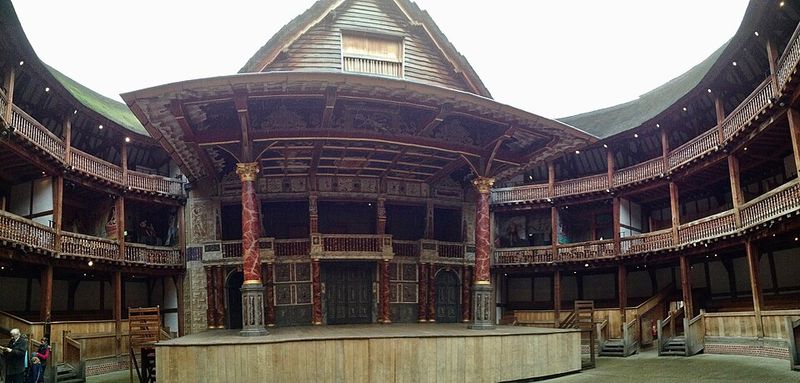

7. The Original Globe Theatre (London, UK)

The original Globe Theatre opened in 1599, home to Shakespeare’s company and audience energy you could feel from the pit. Its circular timber frame and thatched roof framed performances of Hamlet, Othello, and more.

In 1613, a stage cannon set the roof ablaze during Henry VIII.

You cannot visit the original because it burned down and was later replaced and ultimately closed by authorities. A modern reconstruction, Shakespeare’s Globe, stands nearby, researched from period documents.

It offers insight into staging, acoustics, and audience behavior, but it is not the 1599 structure.

When you attend a play today, you get a carefully informed experience shaped by scholarship and safety codes. The theater’s disappearance reminds us how performance spaces evolve with cities.

The original Globe lives through texts, maps, and the ongoing tradition of live drama.

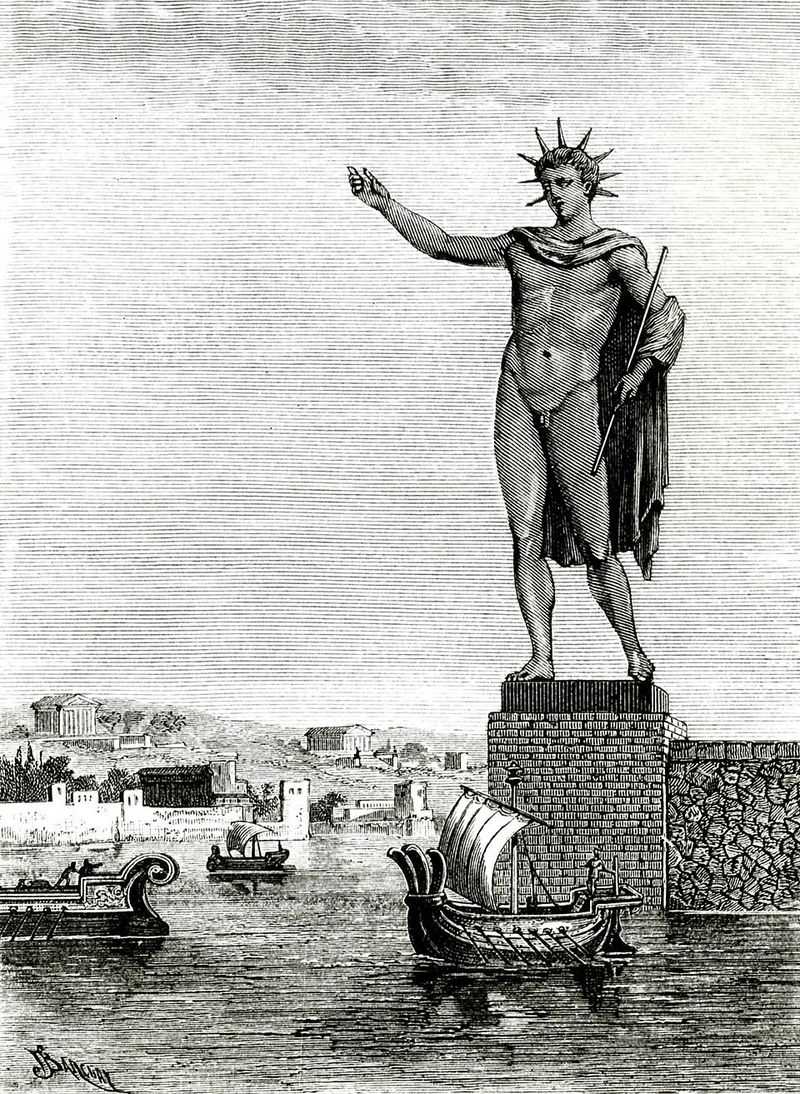

8. The Colossus of Rhodes (Greece)

The Colossus of Rhodes was a gigantic bronze statue of the sun god Helios erected around 280 BCE. Standing to celebrate a military victory, it symbolized civic pride and maritime power.

Ancient sources vary on its exact pose and placement, leaving scholars to piece together possibilities.

You cannot visit because an earthquake around 226 BCE toppled the statue. For centuries, the ruins reportedly lay on the ground before being removed.

No verified remnants survive, and modern proposals to rebuild remain speculative.

When you explore Rhodes today, you will find harbors, fortifications, and museums that contextualize Hellenistic craftsmanship. Exhibits explain casting techniques, internal supports, and the logistics of assembling monumental bronzes.

The Colossus endures as an idea rather than a site, shaping imaginations about ancient engineering.

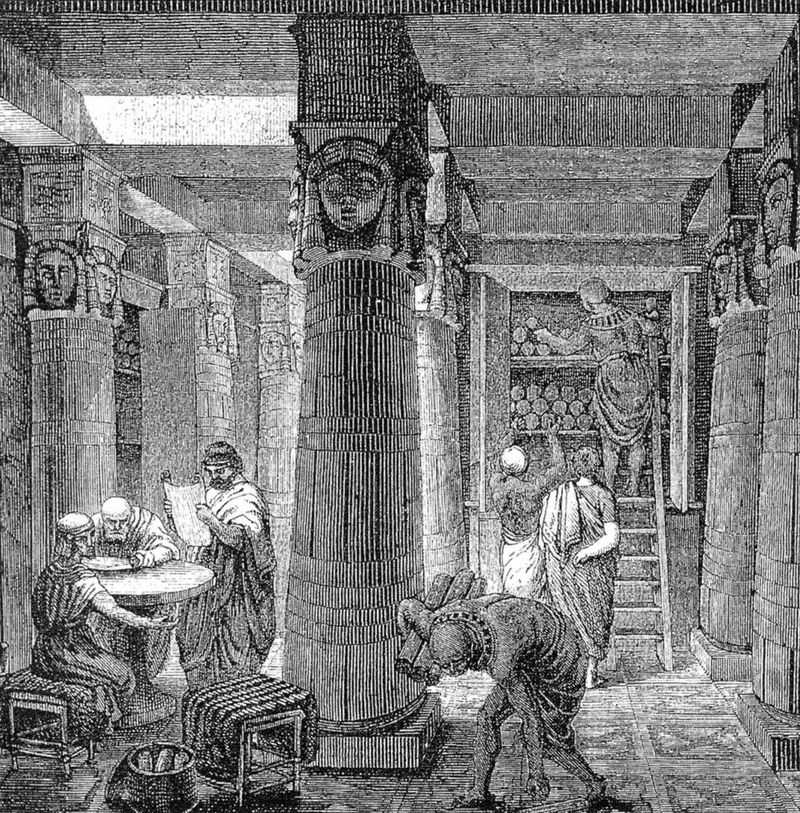

9. The Library of Alexandria (Egypt)

The ancient Library of Alexandria sought to collect the world’s knowledge on papyrus scrolls. It attracted scholars who studied mathematics, medicine, and astronomy, influencing intellectual life across the Mediterranean.

Its precise layout and extent remain debated among historians.

You cannot visit because the original institution vanished through fires, conflict, and gradual decline across centuries. No definitive archaeological footprint survives for the main complex.

Modern Alexandria hosts the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, a contemporary tribute rather than a reconstruction.

When you tour the modern library, exhibits discuss ancient scholarship, translation efforts, and cataloging practices. The story highlights how fragile information can be when politics and storage technology collide.

The idea of a universal library persists, but the rooms and shelves that defined it are lost.

10. The Amber Room (Russia)

The Amber Room was a Baroque masterpiece of amber panels, gilding, and mirrors created in Prussia and installed near St. Petersburg. Tsars used it to impress visiting dignitaries with shimmering light and intricate craftsmanship.

Photographs and inventories convey its luminous power.

You cannot visit the original because it was looted by Nazi forces during World War II and disappeared. Despite extensive searches, its fate remains uncertain.

A painstaking reconstruction at Catherine Palace now recreates the ambiance using period techniques.

If you go today, you will see a faithful homage backed by research and donations. Guides explain how conservators sourced amber, replicated carving, and interpreted black and white references.

The original’s whereabouts are still a mystery, reminding you how art can be both portable and perilously vulnerable.

11. Six Flags New Orleans (USA)

Six Flags New Orleans closed after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when floodwaters inundated rides and infrastructure. The park never reopened, leaving roller coasters and signage to decay.

Security and liability concerns restrict access.

You cannot visit because the site remains shuttered and hazardous. Ownership changes and redevelopment proposals have surfaced, but implementation has been elusive.

The remaining structures are unstable, and trespassing is actively discouraged.

When you drive past the area, you might spot skeletal track silhouettes against the skyline. News reports track cleanup efforts and occasional film shoots using the eerie backdrop.

As a public attraction, though, it is finished, a reminder of disaster impact on private leisure spaces.

12. The Hashima Island Residential Complex (Japan)

Hashima Island, often called Battleship Island, once housed coal miners and their families in dense concrete apartments. At its peak, the island symbolized rapid industrialization and constrained urban living.

After the mines closed in 1974, weather and salt air accelerated decay.

You cannot freely visit most residential blocks because safety risks limit access to guided perimeters. Tours now follow designated routes, keeping you away from collapsing interiors.

The lived spaces remain off limits, preserving fragile structures and visitor safety.

When you take a boat from Nagasaki, guides explain the island’s economy, schools, and rooftop gardens. You will glimpse stairwells, balconies, and courtyards from a distance.

The inaccessible apartments tell a story through absence, framing Japan’s industrial heritage and the cost of abandonment.

13. The Singing Ringing Tree (Original Version) (UK)

The Singing Ringing Tree is a wind powered sound sculpture near Burnley, producing haunting tones as air passes through pipes. The original installation was later replaced to improve durability and tuning.

Its distinctive silhouette has become a local landmark on the moors.

You cannot visit the original version because it no longer stands. The current structure occupies the site and preserves the design concept with updated materials and construction.

It offers a similar acoustic experience, but it is not the first build.

When you arrive on a breezy day, the sound varies with wind speed and direction. Panels discuss engineering choices and weather resilience.

The change illustrates how public art can evolve while maintaining intent, acknowledging maintenance realities in harsh environments.

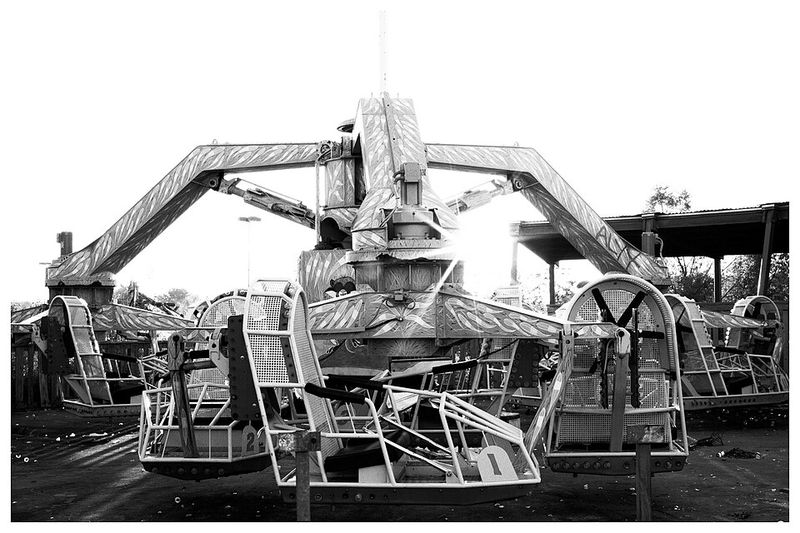

14. Pripyat Amusement Park (Ukraine)

Pripyat’s amusement park was built for the families of Chernobyl plant workers and planned to open in 1986. The disaster occurred days before its official debut, leaving rides unused.

The yellow Ferris wheel became a stark emblem of evacuation and radiation risk.

You cannot freely visit like a normal park because it sits inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Guided tours with controls are possible, but access is tightly managed and conditions change.

Safety protocols dictate how close you can approach certain areas.

When you tour, radiation monitors and briefings set expectations. The site communicates the human scale of nuclear catastrophe more than thrill seeking.

It is not a place for rides, but for reflection on policy, engineering, and emergency response.

15. The Summerland Amusement Park (Isle of Man)

Summerland on the Isle of Man opened in 1971 as a futuristic leisure complex with indoor pools and entertainment. Innovative translucent cladding created a bright environment even on cloudy days.

Families flocked to its slides, arcades, and stages.

You cannot visit because a devastating fire in 1973 destroyed much of the complex, causing tragic loss of life. Investigations raised questions about materials and fire safety.

The site never returned to its original form and was eventually cleared.

When you look up archival images, you see optimism in design contrasted with its vulnerability. Memorials and reports inform modern codes and risk assessment.

The lesson is practical and enduring: fun spaces must be engineered with rigorous attention to safety under stress.