Some discoveries don’t just add to what we know. They change what we think is possible.

For most of history, the world looked like a collection of mysteries that could only be described, not decoded. Then a few people came along and found the hidden pattern underneath the chaos.

One clean idea. One new way to see the problem.

And suddenly, nature stopped looking like magic and started looking like a system.

What makes these breakthroughs so unsettling is how final they feel once you hear them. They don’t sound like “progress.” They sound like the answer that was waiting there the whole time.

And the ripple effects didn’t stay in laboratories. They shaped medicine, technology, space travel, communication, and the way we picture our own place in the universe.

In this roundup, we’re looking at the rare scientists whose single insights didn’t just solve a question. They changed the entire game, and we’re still living inside the world they built.

1. Isaac Newton – Gravity as a Universal Force

Newton didn’t just notice gravity; he realized it was everywhere, working the same way whether you’re dropping your phone or watching Jupiter orbit the Sun. Before him, people thought celestial bodies followed completely different rules than earthly objects.

His mathematical description of gravitational force became the backbone of physics for over two centuries. Engineers still use his equations to launch satellites and predict planetary positions with ridiculous accuracy.

The crazy part? He developed calculus just to solve these problems because the math he needed didn’t exist yet.

Newton’s insight unified heaven and earth under one set of laws, proving the universe runs on consistent principles we can actually understand. That’s not just clever science.

That’s a whole new way of thinking about our place in the cosmos, wrapped up in one elegant idea about why stuff falls down.

2. Charles Darwin – Evolution by Natural Selection

Darwin spent five years sailing around the world on a cramped ship, collecting beetles and getting seasick, only to return home and drop the most controversial idea in biology. Natural selection wasn’t about animals trying to change.

It was about the ones already suited to their environment simply surviving long enough to have babies.

The finches on the Galápagos Islands showed him how: different beak shapes matched different food sources perfectly. Not because birds decided to grow new beaks, but because birds with the right beaks didn’t starve.

Over countless generations, tiny advantages add up to entirely new species.

This single concept explained the stunning diversity of life without needing a supernatural designer constantly tinkering with creation. It gave us a framework for understanding antibiotic resistance, breeding programs, and even human behavior.

Darwin’s idea remains the organizing principle of all modern biology, connecting every living thing through deep time and shared ancestry.

3. Albert Einstein – Space and Time Are Relative

Einstein looked at Newton’s perfectly good gravity theory and said, “Yeah, but what if space itself is bendy?” His general relativity replaced the idea of gravity as a force with something weirder: massive objects actually warp the fabric of spacetime, and other objects roll along those curves like marbles on a stretched rubber sheet.

This wasn’t just philosophical noodling. GPS satellites have to account for Einstein’s predictions or your navigation would be off by miles.

Time genuinely runs slower near massive objects, a fact we can measure with atomic clocks. Black holes, gravitational waves, the expansion of the universe—all of these fall straight out of his equations.

Einstein showed that space and time aren’t fixed stages where events happen. They’re dynamic, flexible, and deeply intertwined.

Reality itself bends, stretches, and flows.

That’s not just a new theory of gravity; it’s a complete reimagining of the universe’s fundamental structure.

4. Nicolaus Copernicus – Earth Is Not the Center of the Universe

For over a thousand years, everyone “knew” Earth sat motionless at the center of everything while the heavens revolved around us. Copernicus whispered, “What if we’ve got it backwards?” and suddenly the math describing planetary motion got way simpler.

Put the Sun in the middle and those weird retrograde loops planets make actually make sense.

He published his heliocentric model basically on his deathbed, probably anticipating the firestorm it would cause. The Church wasn’t thrilled about humans getting demoted from the cosmic VIP section.

But the evidence was too strong to ignore forever.

This shift wasn’t just about astronomy. It fundamentally changed humanity’s self-perception.

We weren’t the universe’s main characters anymore, just inhabitants of one planet among many. That humbling realization opened the door to modern science by suggesting natural laws, not divine whim, govern celestial mechanics.

One simple repositioning of the Sun sparked a revolution in thought.

5. Louis Pasteur – Germ Theory of Disease

Before Pasteur, doctors thought diseases arose spontaneously from bad air or imbalanced bodily humors. They’d go straight from dissecting corpses to delivering babies without washing their hands because why would they?

Pasteur proved that tiny living organisms cause infections, fermentation, and spoilage.

His experiments with swan-necked flasks showed that sterilized broth stayed clear unless exposed to airborne microbes. Suddenly, the invisible world became undeniably real and dangerous.

This insight led directly to antiseptics, sterilization, pasteurization (obviously), and the entire field of microbiology.

Hospitals started cleaning instruments. Cities improved sanitation.

Millions of lives were saved once people accepted that microscopic enemies surrounded us constantly. Pasteur’s germ theory didn’t just advance medicine; it created modern public health.

One idea about invisible critters transformed how we fight disease, preserve food, and understand our relationship with the microbial world that vastly outnumbers us.

6. Gregor Mendel – Traits Are Inherited Through Discrete Units

A quiet monk grew thousands of pea plants in his monastery garden, meticulously tracking whether they were tall or short, green or yellow. Mendel discovered that traits don’t blend like paint colors; they’re passed down in distinct packets we now call genes.

Purple flowers crossed with white didn’t make pale purple—they made purple or white, following predictable mathematical ratios.

His work sat ignored for decades because nobody understood its significance. When scientists finally rediscovered his papers in 1900, genetics exploded as a field.

Suddenly heredity wasn’t mysterious; it followed rules you could predict and test.

Mendel’s insight gave us the foundation for understanding inherited diseases, breeding better crops, and eventually cracking the genetic code itself. Every time doctors discuss genetic risks or farmers develop drought-resistant wheat, they’re building on patterns this patient monk first noticed in his garden.

Discrete inheritance changed biology from descriptive to predictive.

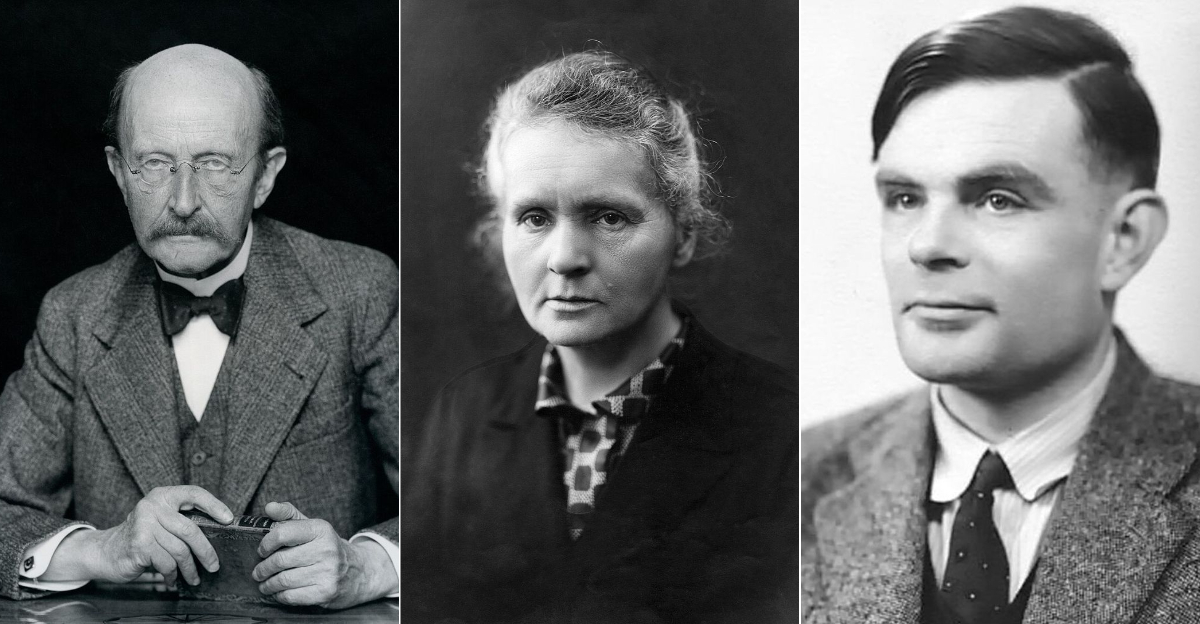

7. Marie Curie – Radioactivity as a Scientific Phenomenon

Curie didn’t discover radioactivity, but she named it, characterized it, and proved it was an atomic property, not a molecular one. Working in a freezing shed with primitive equipment, she isolated radium and polonium from literal tons of pitchblende ore, demonstrating that atoms themselves could transform and emit energy.

This was revolutionary because atoms were supposed to be unchangeable, the fundamental building blocks of matter. Curie showed they could break apart spontaneously, releasing tremendous power.

Her work laid the groundwork for nuclear physics, cancer radiotherapy, and eventually nuclear energy.

She won two Nobel Prizes in different sciences and became the first woman to teach at the Sorbonne, all while her research notebooks remain too radioactive to handle safely even today. Curie’s characterization of radioactivity opened an entirely new chapter in physics, proving matter itself contains hidden depths of energy and transformation we’d never imagined.

8. Galileo Galilei – The Universe Can Be Measured and Tested

Galileo didn’t just make discoveries; he changed how discoveries get made. He insisted that mathematics and experiments trump ancient authority, no matter how respected.

When Aristotle said heavy objects fall faster than light ones, Galileo tested it and proved him wrong. When the Church said celestial bodies were perfect and unchanging, his telescope showed mountains on the Moon and spots on the Sun.

His approach—observe, measure, test, repeat—became the scientific method’s backbone. Truth comes from evidence, not from who said it loudest or longest.

This was dangerous thinking in an era when challenging Aristotle or the Bible could get you imprisoned, which happened to Galileo.

By championing experimental verification over received wisdom, Galileo established science as a separate way of knowing. His legacy isn’t just his discoveries about motion or astronomy; it’s the entire empirical approach that defines modern science.

Question everything, test your ideas, and let nature be the final judge.

9. James Watson & Francis Crick – DNA’s Double Helix Structure

Everyone knew DNA carried genetic information, but nobody knew how until Watson and Crick built their famous double helix model in 1953. Two strands twisted around each other like a spiral staircase, with complementary bases pairing in the middle.

This structure immediately suggested how DNA could copy itself: unzip the strands, and each serves as a template for a new partner.

Their breakthrough relied heavily on Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray crystallography data, though she didn’t get proper credit until much later. The double helix explained heredity at a molecular level, showing exactly how genetic information gets stored, replicated, and passed to offspring.

This single structural insight launched molecular biology as a discipline. It led directly to understanding genetic diseases, developing DNA fingerprinting, creating GMOs, and eventually sequencing entire genomes.

The double helix isn’t just biology’s most famous shape; it’s the key to understanding life’s fundamental operating system.

10. Max Planck – Energy Comes in Discrete Quanta

Planck was trying to solve a boring problem about how hot objects glow when he accidentally kicked off quantum mechanics. Classical physics predicted that heated objects should emit infinite energy at high frequencies, which obviously doesn’t happen.

Planck fixed the math by proposing that energy comes in tiny, indivisible packets he called quanta.

He thought this was just a mathematical trick, a convenient fiction to make the equations work. Turns out, it’s fundamentally true.

Energy really does come in discrete chunks at the atomic level. Light isn’t a continuous wave; it’s made of photons.

Electrons don’t orbit smoothly; they jump between specific energy levels.

This single idea—that energy is quantized—demolished centuries of assumptions about how the universe works at small scales. It led to transistors, lasers, MRI machines, and our entire understanding of atomic structure.

Planck’s reluctant quantum opened a door to a bizarre subatomic realm where probability replaces certainty and particles behave like waves.

11. Michael Faraday – Electricity and Magnetism Are Linked

Faraday was a bookbinder’s apprentice who became one of history’s greatest experimental physicists despite minimal formal education. His big insight?

Moving a magnet near a wire creates electric current. This electromagnetic induction wasn’t just neat; it was the principle behind every generator, transformer, and electric motor ever built.

Before Faraday, electricity and magnetism seemed like separate phenomena. He proved they’re two aspects of the same fundamental force.

Change one, and you create the other. This symmetry became a cornerstone of physics.

His discovery made the modern electrical grid possible. Power plants generate electricity by spinning magnets near coils of wire, exactly as Faraday first demonstrated.

Electric motors reverse the process, using current to create motion. Without electromagnetic induction, we’d have no practical way to generate or use electricity at scale.

Faraday’s linked forces literally power civilization as we know it.

12. Alan Turing – Machines Can Compute Anything

Turing asked a deceptively simple question: what does it mean to compute something? His answer—the Turing machine, a theoretical device that could manipulate symbols according to rules—proved that any calculation could be performed by a sufficiently powerful machine following simple instructions.

This wasn’t about building computers; it was about defining what computation fundamentally is. Turing showed that one universal machine could simulate any other machine, establishing the theoretical foundation for programmable computers.

Every device you own that processes information descends from this insight.

During World War II, he applied these ideas to crack Nazi codes, arguably shortening the war by years. Later, he proposed the Turing Test for machine intelligence, still debated today.

His vision of mechanical computation transformed abstract logic into practical technology.

The digital revolution, artificial intelligence, and the entire information age rest on Turing’s proof that machines can, in principle, compute anything computable.

13. Antoine Lavoisier – Matter Is Conserved

Before Lavoisier, chemistry was barely a science. People thought burning released something called phlogiston, and nobody bothered weighing things carefully.

Lavoisier brought obsessive precision to chemistry, meticulously measuring reactants and products. His conclusion?

Matter isn’t created or destroyed in reactions; it just rearranges.

This law of conservation of mass turned chemistry from medieval alchemy into a quantitative science. Suddenly, chemical equations had to balance.

You could predict how much product you’d get from given reactants. Chemistry became mathematical and therefore predictive.

Lavoisier also named oxygen and hydrogen, explained combustion correctly, and helped establish the metric system. Tragically, he lost his head to the guillotine during the French Revolution.

The judge supposedly said, “The Republic needs neither scientists nor chemists.” Yet Lavoisier’s insistence on careful measurement and conservation laws established chemistry as a rigorous discipline, giving us the tools to understand everything from baking to battery technology.

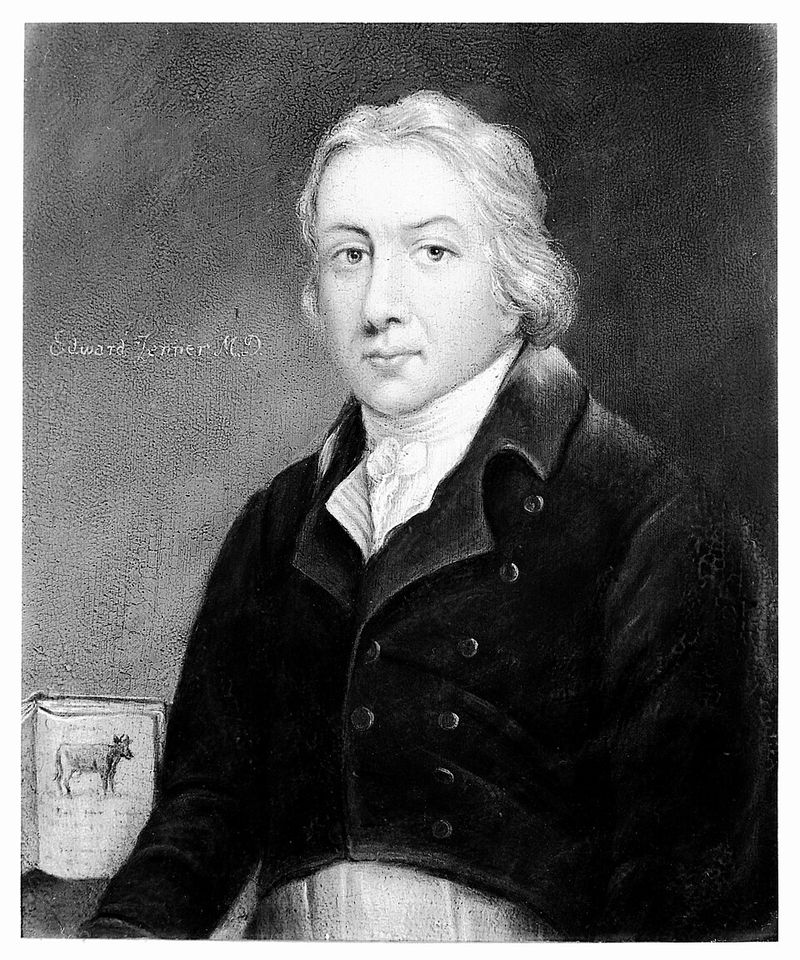

14. Edward Jenner – Vaccination Can Prevent Disease

Jenner noticed that milkmaids who caught cowpox, a mild disease, never got smallpox, a deadly one. So in 1796, he did something that would get him arrested today: he took pus from a cowpox sore and scratched it into an eight-year-old boy’s arm.

Then he exposed the kid to smallpox. The boy didn’t get sick.

This wasn’t the first inoculation attempt, but Jenner proved the principle scientifically and promoted it widely. His cowpox vaccine was safer than earlier smallpox inoculation methods and established that you could train the immune system with a mild exposure to prevent severe disease.

Vaccination became medicine’s most powerful preventive tool. Smallpox killed an estimated 300 million people in the 20th century alone before vaccines eradicated it completely in 1980.

Polio, measles, and countless other diseases now face similar fates.

Jenner’s bold experiment with cowpox gave humanity its first real weapon against infectious disease.

15. Rosalind Franklin – DNA Is a Helical Structure

Franklin was a brilliant X-ray crystallographer whose famous “Photo 51” provided the crucial evidence that DNA forms a helix. Her images showed a distinctive X-pattern that could only come from a helical structure.

Watson and Crick used her data without permission to build their model, and Franklin died before the Nobel Prize was awarded.

Her contribution went beyond one photograph. She also determined DNA’s density, the position of its sugar-phosphate backbone, and key measurements that constrained possible structures.

Without her meticulous experimental work, the double helix model couldn’t have been built.

Franklin’s story highlights both scientific brilliance and historical injustice. She provided critical evidence for one of biology’s most important discoveries but received little credit during her lifetime.

Today, she’s finally recognized as a key architect of our understanding of DNA’s structure.

Her precise experimental approach and the helical evidence she uncovered were absolutely essential to cracking life’s code.