When most people think of Roman ruins, their minds immediately jump to the Colosseum or the Roman Forum. But the Roman Empire stretched far beyond Italy’s borders, leaving behind incredible monuments across three continents.

From massive aqueducts in France to entire cities preserved in Jordan, these lesser-known sites reveal just how powerful and far-reaching ancient Rome truly was.

Pont du Gard — Southern France

Standing nearly 160 feet tall, this magnificent aqueduct bridge proves that Roman engineers were absolute masters at their craft. The three tiers of perfectly balanced arches have survived nearly 2,000 years without a single drop of mortar holding them together.

Each stone was cut so precisely that they lock into place through sheer weight and geometry.

Built in the 1st century AD, Pont du Gard carried water across the river valley to supply the Roman colony of Nemausus, now known as Nîmes. The system transported about 44 million gallons of water daily over a 31-mile route.

What makes this structure even more remarkable is that it drops only one inch every 300 feet, demonstrating incredible surveying accuracy.

Visitors today can walk across the lower tier and explore a museum detailing Roman hydraulic engineering. The golden limestone glows beautifully at sunset, making it a photographer’s dream.

The surrounding parkland offers hiking trails and swimming spots where you can cool off after exploring this engineering marvel that still leaves modern architects scratching their heads in admiration.

Amphitheatre of Pula — Croatia

Six massive structures like this one still stand around the former Roman world, and Pula’s version might just be the most photogenic. Perched on Croatia’s stunning Istrian coast, this arena once roared with the cheers of 23,000 spectators watching gladiators battle for their lives.

The four towering corner structures made it unique among Roman amphitheaters, originally holding wooden staircases and possibly fragrant oils to mask the smell of blood and sweat.

Construction began under Emperor Augustus and wrapped up during Vespasian’s reign in the 1st century AD. Unlike many ancient structures cannibalized for building materials over centuries, Pula’s amphitheater survived remarkably intact.

Its elliptical shape measures about 435 feet long, and the outer wall still reaches heights of over 100 feet in places.

Today, the arena hosts concerts and film festivals, bringing modern entertainment back to its ancient purpose. Underground passages where gladiators once prepared for combat are now open to visitors.

You can practically hear the echoes of ancient crowds as you walk through corridors that once separated life from death by mere minutes.

Jerash — Jordan

Forget Pompeii for a moment—Jerash might actually offer a better glimpse into everyday Roman urban life. This sprawling archaeological site preserves an entire city where you can still walk the same paved streets Roman merchants traveled nearly two millennia ago.

The colonnaded main road stretches over half a mile, flanked by hundreds of towering columns that once supported covered walkways protecting shoppers from the scorching Jordanian sun.

Ancient Gerasa flourished as part of the Decapolis, a group of ten cities that blended Greco-Roman culture with local traditions. The oval forum is particularly unusual, breaking from the typical rectangular Roman design.

Two massive theaters, one seating 3,000 and another accommodating 5,000, still host performances with acoustics that work perfectly without modern amplification.

The hippodrome could hold 15,000 spectators for chariot races, while the Temple of Artemis dominated the skyline with columns reaching 40 feet high. Earthquakes eventually toppled much of the city, but what remains is breathtaking.

Walk through the monumental Hadrian’s Arch, built to welcome the emperor in AD 129, and you’re literally following in imperial footsteps.

Mérida — Spain

Emperor Augustus founded this city in 25 BC as a retirement community for veteran soldiers, and boy, did they build it to last. Augusta Emerita became the capital of Lusitania, one of Rome’s wealthiest provinces, and the monuments here rival anything you’d find in Rome itself.

The theater alone seats 6,000 people and still stages classical performances every summer, bringing ancient dramas back to their original setting.

The Roman bridge spanning the Guadiana River stretches an incredible 2,575 feet, making it one of the longest surviving Roman bridges anywhere. Sixty arches carry the structure across the water, and it remained in use for vehicular traffic until 1991.

The aqueduct system includes the impressive Acueducto de los Milagros, where towering brick pillars march across the landscape like ancient giants frozen in time.

Don’t miss the amphitheater, which held 15,000 spectators for gladiatorial combat, or the circus where 30,000 Romans cheered chariot races. The National Museum of Roman Art houses incredible mosaics, statues, and everyday objects that paint a vivid picture of provincial life.

UNESCO recognized the entire archaeological ensemble as a World Heritage Site in 1993.

Bath — England

Hot water still bubbles up from the earth at 115 degrees Fahrenheit, just as it did when Roman soldiers first discovered these springs nearly 2,000 years ago. They built an elaborate bathing complex that transformed a Celtic sacred site into a Roman social hub where people gathered to bathe, gossip, conduct business, and worship the goddess Sulis Minerva.

The Great Bath, filled with naturally heated mineral water, remains the centerpiece of a remarkably preserved complex.

Romans called the settlement Aquae Sulis, and it became one of Roman Britain’s most important spa towns. The engineering required to capture, channel, and drain over 240,000 gallons of hot water daily was extraordinary.

Lead pipes, stone channels, and heated floors created a sophisticated system that kept bathers comfortable even during Britain’s notoriously cold winters.

Walking through the site today feels like time travel. You can peer into the Sacred Spring where Romans tossed curse tablets asking gods to punish thieves who stole their clothing.

The museum displays coins, jewelry, and even the gilded bronze head of the goddess Sulis Minerva. Steam still rises from the green thermal waters, connecting modern visitors to ancient bathers across the centuries.

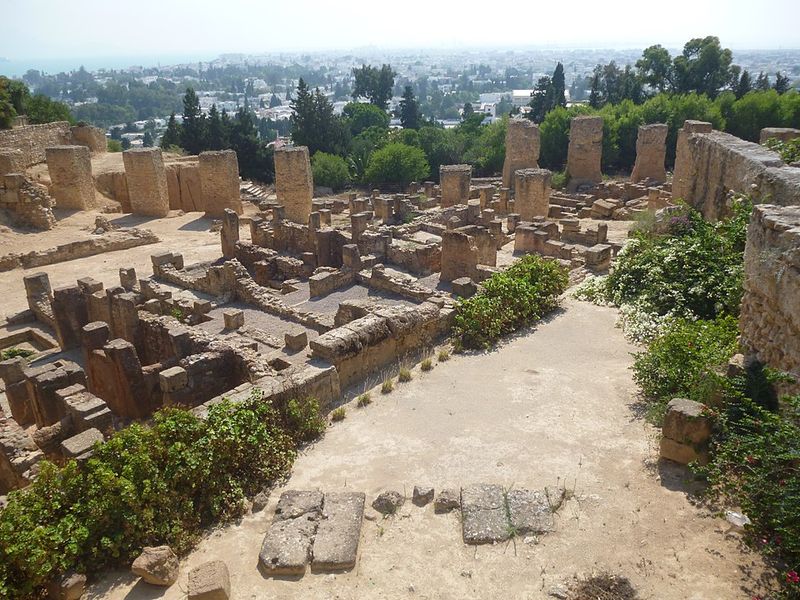

Carthage — Tunisia

Rome utterly destroyed this city in 146 BC, salting the earth in legendary fury after three brutal Punic Wars. But empires are practical, and within a century, Romans rebuilt Carthage into one of their most prosperous Mediterranean cities.

What rose from the ashes became a glittering provincial capital that rivaled Alexandria and Antioch in wealth and importance.

The Baths of Antoninus Pius, constructed in the 2nd century AD, were the largest Roman baths in Africa and third-largest in the entire empire. Though mostly ruins today, one standing column towers over 50 feet high, hinting at the complex’s former grandeur.

The site sprawled across several acres with hot rooms, cold plunges, exercise yards, and libraries where Romans spent entire afternoons socializing.

Scattered across the hills overlooking the Mediterranean, you’ll find theater remains, villa foundations with stunning mosaic floors, and the Antonine Baths’ underground service tunnels. The amphitheater once held 36,000 spectators.

Byrsa Hill offers panoramic views and houses a museum with Punic and Roman artifacts. Walking these ruins, you can almost hear the echoes of a city that refused to stay dead, rising from destruction to become Rome’s African jewel.

Nîmes — France

This southern French city boasts Roman monuments in such pristine condition that you might wonder if someone secretly restored them last week. The Maison Carrée temple, built around 16 BC, ranks among the best-preserved Roman temples anywhere on Earth.

Its Corinthian columns and classical proportions inspired countless neoclassical buildings, including Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia State Capitol. Napoleon was so smitten that he wanted to dismantle it and move it to Paris.

The Arena of Nîmes is a smaller cousin to Rome’s Colosseum but arguably in better shape. Built around AD 70, it held 24,000 spectators for gladiatorial games and still hosts bullfights and concerts today.

The two-story facade features 60 arches, and unlike the Colosseum, its upper levels remain mostly intact.

The Jardins de la Fontaine incorporates Roman ruins into beautiful 18th-century gardens, including the Temple of Diana and the Tour Magne watchtower. And just 15 miles away stands Pont du Gard, completing this region’s incredible Roman trifecta.

Nîmes was clearly a favorite of Roman city planners, and walking its streets reveals why. The preservation here borders on miraculous, offering a time capsule of provincial Roman life.

Segovia — Spain

Picture 24,000 granite blocks stacked 93 feet high without a single drop of cement or mortar holding them together. That’s exactly what Roman engineers accomplished here around AD 50, creating an aqueduct that carried mountain water 10 miles to Segovia and remained functional until the mid-19th century.

The structure’s 167 arches march through the city’s heart like a stone giant’s backbone, defying both gravity and time.

Each block was precision-cut to interlock perfectly, relying on compression and balance rather than adhesives. The double-tiered arcade creates a dramatic visual effect as it crosses the Plaza del Azoguejo, where it reaches its maximum height.

Locals called it “El Puente” (The Bridge), though it never actually crossed water at this point—just air and architectural ambition.

The aqueduct transported water from the Frío River in the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains, maintaining a steady gradient that kept water flowing downhill the entire route. What’s truly mind-blowing is that this wasn’t just decorative architecture—it was working infrastructure for nearly 2,000 years.

Today, it’s Segovia’s most iconic landmark, dramatically lit at night and surrounded by cafés where you can sip wine while contemplating ancient engineering genius that modern builders still study in awe.

Split & Diocletian’s Palace — Croatia

Emperor Diocletian retired here in AD 305 after becoming the first Roman emperor to voluntarily abdicate, choosing to spend his final years growing cabbages by the Adriatic Sea. His retirement home happened to be a massive fortified palace covering nearly 10 acres, with walls reaching 70 feet high in places.

But here’s where it gets really interesting: the palace never became a ruin because people never stopped living in it.

Over 1,700 years, residents built homes, shops, and churches inside the ancient walls, creating a living museum where modern life flows through Roman corridors. The basement halls where servants once scurried now host art exhibitions and souvenir shops.

The peristyle courtyard, where Diocletian held court, serves as a public square where tourists sip coffee beneath 1,700-year-old columns.

The Cathedral of Saint Domnius was originally Diocletian’s mausoleum—ironic since he persecuted Christians, yet his tomb became a church. The Temple of Jupiter transformed into a baptistery.

Exploring Split means wandering through a time-layered labyrinth where every corner reveals another era. You might exit a Roman gateway to find yourself in a medieval alley that opens onto a Renaissance square.

It’s architectural time travel at its finest, proving that the best way to preserve history is to keep living in it.

Cologne — Germany

Modern Cologne sits atop Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, one of ancient Germania’s most important Roman cities and the birthplace of Agrippina the Younger, Emperor Nero’s mother. Founded in AD 50, it served as the provincial capital and a crucial military base along the Rhine frontier.

Today, Roman remnants peek out between modern buildings like archaeological Easter eggs hidden throughout the city.

The Romano-Germanic Museum was literally built around the spectacular Dionysus mosaic, discovered during World War II air raid shelter construction. This 3rd-century floor depicts scenes from the wine god’s mythology in stunning detail, with over a million colored tiles creating intricate images.

The museum houses an incredible collection of Roman glass—Cologne was famous for glassmaking—along with jewelry, weapons, and everyday objects that illuminate life on Rome’s northern frontier.

Sections of the original Roman city wall still stand, including a preserved gate tower. The Praetorium, the governor’s palace, lies beneath the modern city hall, accessible through underground passages.

Walking Cologne’s streets, you’re literally walking above Roman roads, houses, and workshops. The city celebrates this layered history, with glass panels in sidewalks revealing archaeological excavations below.

It’s a reminder that Roman influence reached far beyond the Mediterranean, planting seeds of urban culture in the forests of Germania.

Hadrian’s Wall — United Kingdom

Imagine building a wall 73 miles long across some of Britain’s most rugged terrain, complete with a fort every five miles and turrets between them. That’s exactly what Emperor Hadrian ordered in AD 122, creating the most heavily fortified border in the entire Roman Empire.

This wasn’t just a wall—it was a complex military zone with ditches, earthworks, and a military road running behind it, controlling movement between Roman Britain and the unconquered tribes to the north.

At its peak, roughly 9,000 soldiers manned the wall’s forts and milecastles, representing units from across the empire. Soldiers from modern-day Spain, Syria, Romania, and North Africa shivered through British winters along this remote frontier.

They left behind letters, including the famous Vindolanda tablets—thin wooden postcards that preserve everything from military reports to birthday party invitations, offering touching glimpses into soldiers’ daily lives.

Today, the best-preserved sections run through Northumberland National Park, where the wall snakes dramatically across hilltops and valleys. Housesteads Fort remains remarkably intact, complete with barracks, granaries, and communal latrines where soldiers sat side-by-side.

Walking the wall path is now a popular multi-day hike, following in the footsteps of Roman sentries who once gazed north toward mysterious Caledonia, wondering what lay beyond civilization’s edge.

Aquincum — Budapest, Hungary

Budapest’s Óbuda district hides the remains of Aquincum, once the thriving capital of the Roman province of Pannonia. Around 40,000 people lived here at its peak in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, making it one of the empire’s significant eastern outposts.

The Danube River served as a crucial frontier, and Aquincum functioned as both military headquarters and civilian administrative center, controlling trade routes and defending against Germanic tribes.

The archaeological park reveals a surprising amount: a well-preserved amphitheater that held 16,000 spectators, bath complexes with intricate heating systems, and a grid of streets lined with house foundations. You can trace the outline of shops, workshops, and homes, imagining the bustling market days when merchants sold everything from local pottery to imported olive oil.

The military amphitheater, separate from the civilian one, lies nearby and could accommodate 12,000-15,000 soldiers and residents.

The Aquincum Museum displays extraordinary finds including an ancient water organ, bronze statues, jewelry, and colorful frescoes that once decorated wealthy homes. Tombstones and altars reveal the religious diversity of this frontier city, where traditional Roman gods mingled with local Celtic deities and Eastern mystery cults.

Standing among these ruins with the Danube flowing past, you sense how Rome’s reach extended far beyond the Mediterranean, bringing urban sophistication to the edge of the known world.

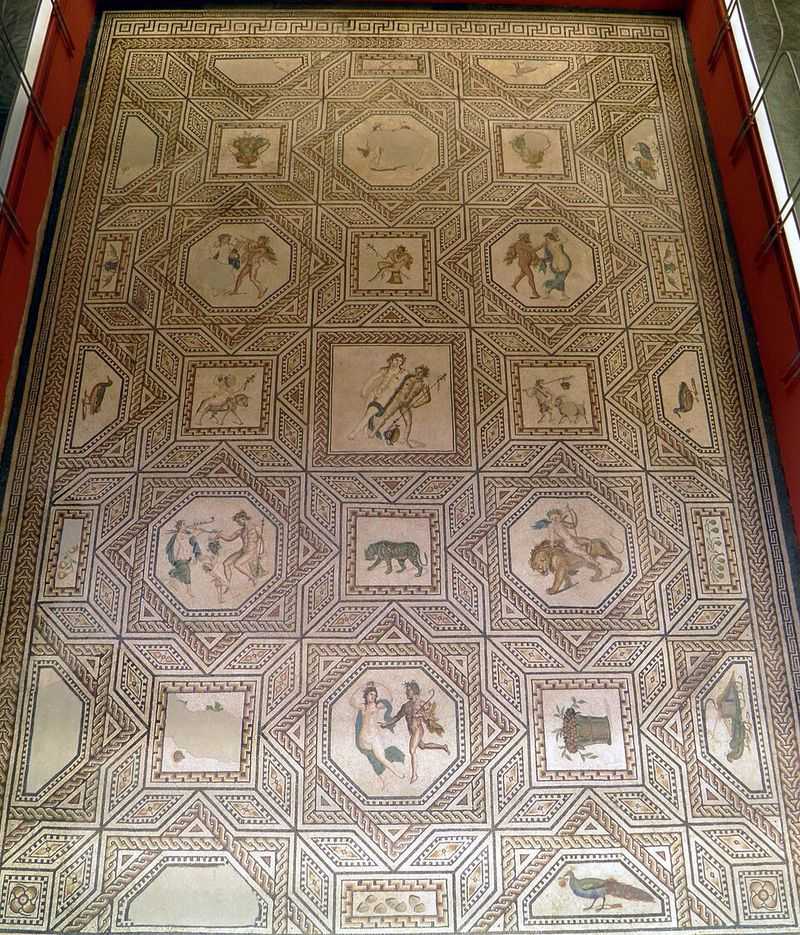

Domus Romana — Malta

Sometimes the most revealing historical sites aren’t grand temples or massive amphitheaters but ordinary homes where regular people actually lived. The Domus Romana in Malta offers exactly that—an intimate glimpse into domestic life in a wealthy Roman household from the 1st century BC.

Discovered in 1881, this aristocratic townhouse near Mdina preserves stunning mosaic floors that survived nearly intact beneath centuries of soil and later construction.

The mosaics are genuinely breathtaking, featuring geometric patterns, marine scenes with dolphins and octopuses, and intricate designs that demonstrate the homeowner’s wealth and sophisticated taste. Romans loved showing off through interior decoration, and these floors were their Instagram—permanent displays of status and culture.

The quality suggests professional craftsmen, possibly imported from Italy or North Africa, traveled to this Mediterranean island to create these masterpieces.

The attached museum houses marble statues, pottery, glassware, coins, and personal items excavated from the site and surrounding areas. You’ll see oil lamps that once illuminated evening meals, jewelry worn at social gatherings, and cooking vessels used in the home’s kitchen.

Malta was a crucial stopping point on Mediterranean trade routes, and artifacts here reflect connections spanning from Carthage to Rome. It’s a reminder that Roman culture wasn’t just about emperors and armies—it was also about families decorating their homes, hosting dinner parties, and living daily lives remarkably similar to our own.

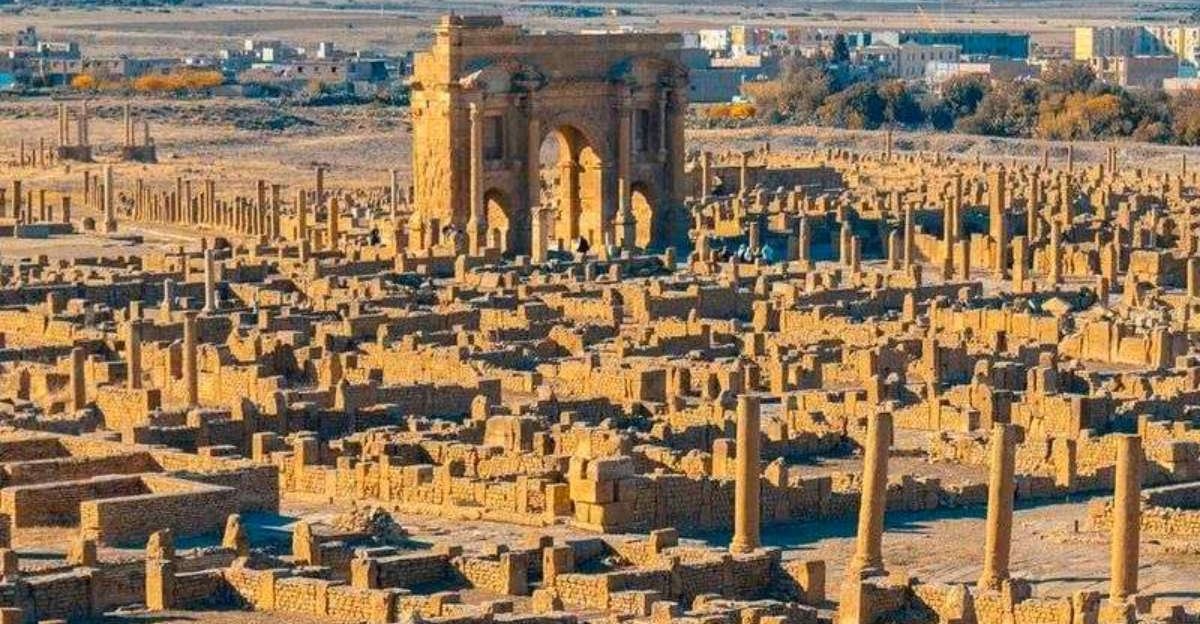

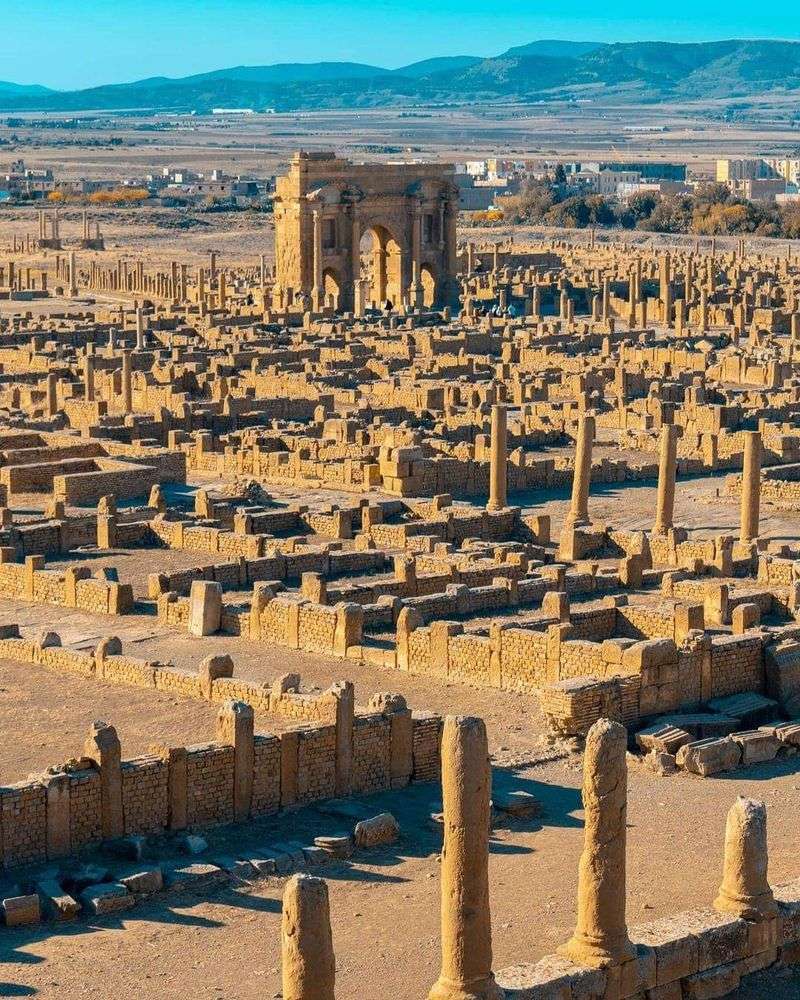

Timgad — Algeria

Emperor Trajan founded Timgad around AD 100 as a military colony for veterans, and city planners laid it out with textbook Roman precision. The grid pattern is so perfect that it looks like someone drew it with a ruler—which they essentially did.

Streets intersect at right angles, creating uniform blocks (insulae) in a design that would influence urban planning for the next two millennia. From above, it resembles a miniature Roman blueprint preserved in stone.

The city’s original footprint covered about 30 acres, though it eventually expanded beyond its original square layout as prosperity attracted more residents. Trajan’s Arch, standing 40 feet tall, marked the western entrance.

The theater seated 3,500 people and remains in remarkable condition, with many original seats still in place. The forum, temples, public baths, and even a public library demonstrate how Romans transplanted their entire urban lifestyle into North Africa’s interior.

What makes Timgad extraordinary is its completeness and isolation. Sand preserved what time and scavengers destroyed elsewhere.

Walking these streets, you can trace the daily routes ancient residents took from home to forum to baths. The library is particularly special—one of only a handful of Roman libraries identified archaeologically.

UNESCO designated it a World Heritage Site, recognizing it as one of the finest examples of Roman town planning anywhere, a frozen snapshot of imperial ambition in the African desert.

Early Christian Necropolis — Pécs, Hungary

Death in ancient Rome was a serious business, especially after Christianity began spreading through the empire in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. The burial complex beneath Pécs (Roman Sopianae) preserves some of Europe’s most beautiful early Christian funerary art, hidden underground for over 1,600 years.

These aren’t just holes in the ground—they’re elaborately decorated chambers where wealthy Christian families laid their dead to rest with stunning painted prayers covering every surface.

The tombs feature vivid frescoes depicting biblical scenes: Adam and Eve, Daniel in the lions’ den, and early Christian symbols like fish, peacocks, and grapevines. The colors—reds, blues, greens, and golds—remain remarkably bright, protected by the cool, stable underground environment.

These images reveal how Christianity adapted Roman artistic traditions, blending classical style with new religious messages. The craftsmanship rivals contemporary Roman art anywhere in the empire.

Pécs served as an important administrative center in the province of Pannonia, and its Christian community was clearly prosperous and influential. The necropolis includes both above-ground memorial chapels and underground burial chambers, some containing multiple generations of the same family.

UNESCO recognized the site’s exceptional importance in 2000. Visiting these tombs connects you to a pivotal moment when the Roman world was transforming from pagan to Christian, one beautifully painted burial chamber at a time.