Beneath our feet lies a hidden world of ancient tunnels, carved chambers, and entire cities where thousands once lived, worked, and survived. From the volcanic rock labyrinths of Turkey to wartime shelters across Europe, these underground settlements reveal how humans have always sought refuge and community below the surface.

Some were built to escape invaders, others to endure harsh climates or war, but all showcase incredible engineering and resilience. Join me as we explore these remarkable subterranean worlds that once buzzed with life.

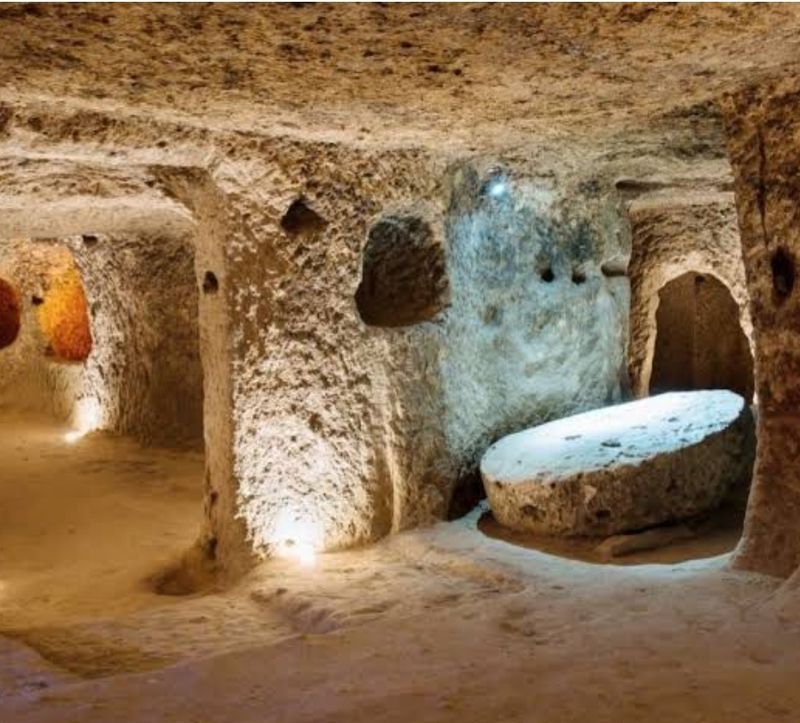

Derinkuyu Underground City — Turkey

Carved into soft volcanic rock beneath Cappadocia’s surreal landscape, Derinkuyu plunges more than 85 meters below ground and once sheltered up to 20,000 souls. Picture entire families living in darkness, raising livestock, pressing wine, and praying in chapels—all while hidden from invading armies above.

The city dates back as early as the 8th century BC, and its multi-level maze includes living quarters, storage rooms, and ingenious ventilation shafts that kept air flowing even when massive stone doors sealed everyone inside. Walking through Derinkuyu today feels like stepping into a science fiction novel, except it’s all real.

The engineering brilliance is staggering—how did ancient people carve such intricate networks without modern tools? Each level connects through narrow passageways that could be blocked instantly during attacks, turning the city into an impenetrable fortress.

Derinkuyu wasn’t just a hiding spot; it was a fully functioning underground society. People lived here for months at a time, creating a thriving community in near-total darkness.

The scale and sophistication make it one of humanity’s most astonishing achievements, proving that when survival is at stake, humans can build entire worlds beneath the earth.

Kaymakli Underground City — Turkey

Unlike Derinkuyu’s dramatic vertical descent, Kaymakli spreads horizontally like an underground ant farm, with eight levels of tunnels snaking through Cappadocia’s volcanic rock. Dating back to at least the 7th century BC and expanded through Roman and Byzantine times, this sprawling settlement housed thousands during periods of persecution and war.

The maze includes kitchens, storage rooms, wineries, churches, and even graves—everything needed for long-term survival underground. What strikes me most about Kaymakli is how methodically planned it feels.

Ventilation shafts ensured fresh air reached every corner, while narrow corridors forced invaders to enter single-file, making defense easier. Families carved out living spaces complete with stone beds and niches for oil lamps, creating surprisingly cozy homes deep beneath the surface.

Archaeologists believe Kaymakli connected to other underground cities through miles of tunnels, forming a vast subterranean network. Imagine traveling between cities without ever seeing daylight!

The community here wasn’t just hiding—they were thriving, maintaining trade, worship, and daily routines. Kaymakli shows us that underground life could be complex, organized, and genuinely livable for extended periods.

Özkonak Underground City — Turkey

A curious farmer stumbled upon Özkonak in 1972 while tending his land, unknowingly uncovering another Cappadocian marvel. Carved into the same soft volcanic rock as its famous neighbors, this underground city features something special—unique communication pipes that allowed residents to send messages between levels.

Imagine shouting down a stone tube to warn your family of approaching danger or to call everyone for dinner! Özkonak’s ventilation system is equally impressive, with shafts cleverly designed to circulate fresh air throughout the complex. The city likely served as a refuge during invasions, with massive millstone doors that could be rolled into place to seal entrances.

Generations lived here in total darkness, yet they managed to create a functioning society complete with storage rooms, living quarters, and defensive features. What fascinates me is how each Cappadocian underground city has its own personality. Özkonak feels more intimate than Derinkuyu, with narrower passages and a cozier layout.

The communication pipes add a human touch—you can almost hear ancient voices echoing through them. These weren’t just survival shelters; they were homes where people laughed, argued, raised children, and built community bonds in the most unlikely place imaginable.

Mazı Underground City — Turkey

Tucked near Ürgüp, Mazı Underground City gets fewer tourists than its famous cousins, but it’s equally fascinating. Dating back to the Roman period with later Byzantine modifications, this hidden world contains tombs and chambers suggesting people sought underground shelter not just temporarily but for entire community living.

Central halls provided gathering spaces, while defensive entrances featured those ingenious millstone-style doors that could seal the city in seconds. I find something poignant about Mazı’s relative obscurity.

While thousands flock to Derinkuyu, this quieter site lets you really imagine what underground life felt like. The air is cool and still, and you can almost hear the whispers of ancient inhabitants going about their daily routines.

The presence of tombs indicates people didn’t just hide here—they lived full lives, including burying their dead within the underground complex. The Roman and Byzantine layers reveal how the city evolved over centuries, with each civilization adding its own architectural touches.

Storage rooms held enough food to sustain communities during long sieges, while ventilation systems prevented the air from becoming stale. Mazı proves that underground cities weren’t one-time emergency shelters but multi-generational homes that adapted to changing needs and threats over hundreds of years.

Aydıntepe Underground City — Turkey

Way up in northeastern Turkey, Aydıntepe proves that underground cities weren’t just a Cappadocian phenomenon. This layered marvel features halls, connected rooms, ventilation shafts, and storage—all carved below the surface in a completely different region.

Though smaller than the Cappadocian giants, Aydıntepe’s existence reveals how widespread subterranean living was across ancient Anatolia. What makes Aydıntepe special is its regional variation.

The architecture differs slightly from Cappadocia’s volcanic rock cities, showing how different communities adapted underground construction to their local geology. People here faced similar threats—invasions, persecution, harsh weather—and arrived at similar solutions: go underground.

The connected rooms suggest family units lived side-by-side, creating tight-knit communities in confined spaces. Visiting Aydıntepe feels like discovering a secret that history almost forgot.

It’s not on most tourist maps, which means you can explore without crowds and really absorb the atmosphere. The ventilation shafts still work after centuries, a testament to ancient engineering skills.

Storage areas indicate people planned for long stays, stocking supplies and preparing for extended periods underground. Aydıntepe reminds us that underground cities were a widespread survival strategy, not just isolated oddities in one famous region.

Agongointo-Zoungoudo — Benin’s Hidden Town

Near Abomey in Benin, West Africa, lies a different kind of underground marvel—Agongointo-Zoungoudo, where housing structures and bunkers sit about 10 meters below ground. Built in the 17th century, these spaces served dual purposes: dwelling areas for families and military installations for strategic defense.

This wasn’t just about hiding from enemies; it was about creating a tactical advantage while maintaining community life below the surface. African underground cities get less attention than their European and Asian counterparts, but they’re equally impressive.

The Benin site showcases how diverse cultures independently arrived at underground living as a solution to security threats. The military aspect is particularly interesting—soldiers could launch surprise attacks from below while civilians remained safe in deeper chambers.

It’s guerrilla warfare meets urban planning. The 17th century timing coincides with regional conflicts and the slave trade era, suggesting these underground towns provided crucial protection during tumultuous times.

Families carved out living spaces with surprising comfort, creating homes that felt secure and permanent. Agongointo-Zoungoudo proves that underground cities weren’t just Mediterranean or Middle Eastern phenomena—they appeared wherever people needed safety, showing the universal human instinct to dig deep when danger threatens from above.

Naours Underground City — France

Beneath a quiet village in northern France, La Cité Souterraine de Naours extends over a mile of tunnels and chambers dating back to the 3rd century. Used through the 17th century, this underground refuge became a complete medieval town during invasions, featuring more than 300 chambers including chapels, living quarters, and even bakeries.

Yes, bakeries! People baked bread underground, filling the tunnels with the smell of fresh loaves while enemies searched for them above.

Naours shows us that underground cities weren’t just an Eastern phenomenon. Medieval Europeans also embraced subterranean living when threatened, creating surprisingly comfortable spaces below ground.

The chapels indicate that spiritual life continued underground—people prayed, celebrated services, and maintained their faith even in darkness. The bakeries are particularly clever, with ventilation systems that dispersed smoke so it wouldn’t give away their location.

I’m amazed by how livable Naours must have been. The chambers are spacious enough to avoid claustrophobia, and the layout suggests careful planning rather than desperate digging.

Families carved niches for belongings and sleeping areas, while communal spaces allowed social interaction. During World War I, soldiers sheltered here and left graffiti that’s still visible today, adding modern layers to this ancient hideout.

Naours proves that underground refuge was a European survival strategy spanning nearly two millennia.

Catacombs of Paris — France

Six million skeletons rest beneath Paris in a labyrinth that stretches for miles under the bustling French capital. Created in the late 18th century when cemeteries overflowed and became health hazards, the Catacombs transformed abandoned limestone quarries into a vast underground necropolis.

While not a living city in the traditional sense, this subterranean world illustrates how urban populations used underground spaces to solve pressing problems—in this case, where to put millions of dead bodies. Walking through the Catacombs feels surreal.

Walls of carefully arranged skulls and femurs line narrow passages, creating macabre art installations that have fascinated visitors for centuries. The sheer scale is overwhelming—six million people!

That’s more than the current population of many countries, all resting in organized chaos below one of the world’s most romantic cities. The Catacombs also became a refuge for the living at various points in history.

During World War II, French Resistance fighters used the tunnels for secret meetings and operations, while Nazi soldiers established bunkers down there. Today, urban explorers illegally navigate unmapped sections, hosting secret parties and creating underground art.

The Catacombs prove that underground spaces serve many purposes beyond their original intent, evolving to meet each generation’s needs.

Setenil de las Bodegas — Spain’s Cave Settlement

Homes literally grow out of cliff faces in Setenil de las Bodegas, where massive rock overhangs serve as roofs for whitewashed houses. Located in southern Spain, this isn’t entirely underground, but it brilliantly showcases how ancient communities exploited rock-carved spaces for shelter and daily life.

The town’s name comes from the Latin “septem nihil” (seven times nothing), supposedly referencing the seven attempts it took Christian forces to conquer it from Moorish defenders—those rock walls made excellent fortifications! Walking through Setenil feels like stepping into a fairy tale.

Houses nestle under rock overhangs so massive they’ve protected buildings for centuries from rain, sun, and time itself. Some dwellings extend back into the cliff, creating cool, cave-like interiors perfect for Spain’s hot summers.

Bars and restaurants now occupy many of these rock-sheltered spaces, where you can sip wine while literally sitting inside a mountain. The settlement pattern here reveals ancient wisdom about working with nature rather than against it.

Why build a roof when a million-year-old rock ledge does the job better? The rock provides natural insulation, keeping homes cool in summer and warm in winter.

Setenil proves that underground and rock-carved living isn’t just about emergency refuge—it’s also about smart, sustainable architecture that uses natural features to create comfortable, lasting homes.

Cappadocia’s Hidden Network — Turkey

Beyond the famous sites, Cappadocia contains hundreds of lesser-known underground cities and tunnels that once interconnected entire regions. Archaeologists keep discovering new sections, revealing a subterranean world far more extensive than anyone imagined.

These networks served as extended population centers during wars, with tunnels allowing people to travel between cities without surfacing. Imagine an ancient subway system, except carved by hand through volcanic rock!

The interconnected nature of these cities suggests sophisticated planning and cooperation between communities. When danger threatened, entire populations could disappear underground, moving through tunnels to safer locations if one city became compromised.

Storage chambers dotted the network, ensuring food and supplies remained accessible wherever people sheltered. It’s urban planning on a massive, three-dimensional scale.

What blows my mind is how much remains undiscovered. Farmers still occasionally break through into previously unknown chambers while plowing fields.

Each new discovery reveals more about how extensive underground living was in ancient Anatolia. Some tunnels extend for miles, with multiple exits disguised as wells or hidden in rock formations.

This wasn’t just a few isolated cities—it was an entire parallel civilization existing below ground, complete with infrastructure, trade routes, and community networks that sustained thousands for generations.

York’s Underground Vaults — UK

Medieval cellars and vaults snake beneath York’s ancient streets, creating a hidden layer of urban life that supported commerce and daily existence for centuries. While not designed as a refugee city, these underground spaces became essential to York’s economy—merchants stored goods, traders conducted business, and residents sought shelter during conflicts.

The vaults reveal how underground spaces naturally emerged as cities grew denser and more complex. York’s underground areas have a distinctly medieval character, with stone arches, thick walls, and that damp, earthy smell of centuries-old masonry.

Some cellars connect to each other, forming impromptu tunnel systems where people could move between buildings without going outside—handy during York’s brutal winters or when Viking raiders came calling. Taverns often had underground sections where ale was stored and, rumor has it, where shadier business transactions occurred away from official eyes.

Today, ghost tours lead visitors through these vaults, spinning tales of hauntings and historical drama. But the real story is how ordinary people used underground spaces for practical purposes—storage, workshops, meeting places, and emergency shelter.

York’s vaults weren’t grand engineering projects like Derinkuyu; they were organic developments that grew as the city needed them, proving that underground urban life could emerge naturally from commercial and social needs rather than just military necessity.

Wieliczka Salt Mine — Poland

Carved entirely from salt over seven centuries, Wieliczka near Kraków evolved from a mine into an underground wonderland where entire communities lived and worked. The complex extends over 178 miles of tunnels and reaches depths of 1,073 feet, containing chapels, ballrooms, and chambers large enough to host concerts.

Miners didn’t just extract salt—they created an entire subterranean civilization complete with art, worship spaces, and social areas. The chapels are breathtaking.

Everything—walls, floors, altars, even chandeliers—is carved from salt, creating ethereal spaces that glow in lamplight. Miners spent their spare time creating these masterpieces, transforming a workplace into a sacred space.

The Chapel of St. Kinga is the size of a small church, with intricate salt sculptures depicting biblical scenes. It’s like walking into a fairy tale made of crystallized minerals.

Wieliczka shows how underground spaces can become communities rather than just workplaces. Miners’ families sometimes lived below ground for extended periods, and the mine developed its own culture, traditions, and social hierarchy.

The stable temperature and humidity even made certain chambers ideal for health treatments, leading to an underground sanatorium. Today, Wieliczka remains a working site while also being a UNESCO World Heritage location, proving that underground spaces can serve multiple purposes simultaneously across centuries.

Montreal’s Underground City — Canada

Officially called RESO, Montreal’s Underground City is a modern marvel where thousands live, work, shop, and commute entirely below ground. Spanning over 20 miles of tunnels connecting shopping centers, office buildings, hotels, metro stations, and residential complexes, it’s the largest underground urban network in the world.

During Montreal’s brutal winters, when temperatures plummet and snow buries streets, this climate-controlled subterranean world becomes the city’s real downtown. I visited Montreal in February once and barely went outside for three days.

Everything I needed—restaurants, shops, entertainment, transit—existed underground in a comfortable 70-degree environment while a blizzard raged above. Half a million people use RESO daily during winter, creating a bustling underground city that feels surprisingly normal.

There are no damp stone tunnels here—just bright, modern corridors lined with stores and cafes. Montreal proves that underground cities aren’t just historical curiosities.

When climate demands it, modern populations will happily embrace subterranean living. The network keeps expanding as new buildings connect to the system, creating an ever-growing underground metropolis.

It’s not about hiding from invaders anymore—it’s about creating comfortable, functional urban spaces regardless of surface conditions. RESO shows us the future of underground cities: climate-controlled, commercially vibrant, and fully integrated into daily urban life.

Beijing’s Underground Shelters — China

During the Cold War, paranoia about nuclear attack led Beijing to construct a massive underground shelter system called Dìxià Chéng, or “The Dungeon.” At its peak, this subterranean network stretched over 85 square kilometers beneath the Chinese capital, complete with classrooms, restaurants, medical facilities, and living quarters. Around a million people reportedly lived there at various points, creating a shadow city beneath Beijing’s bustling streets.

The scale is staggering. Entire schools operated underground, with children attending classes in windowless rooms lit by fluorescent lights.

Restaurants served meals to workers who spent their entire shifts below ground. The tunnel system connected to the metro, government buildings, and residential areas, allowing rapid evacuation if nuclear war erupted.

It was Cold War paranoia transformed into concrete and steel, a city built for Armageddon that thankfully never came. After the Cold War ended, sections of Dìxià Chéng were opened to tourists, while other parts became budget housing for migrant workers.

Walking through these tunnels feels eerie—propaganda posters still line walls, and the utilitarian design screams 1960s Communist functionality. Beijing’s underground city represents a unique moment in history when governments convinced entire populations that living like moles was necessary for survival.

It’s both fascinating and deeply unsettling, a monument to fear that became an accidental community.

Sarajevo’s Tunnel of Hope — Bosnia and Herzegovina

During the 1990s siege of Sarajevo, when the city was surrounded and cut off from the world, residents dug a lifeline beneath the airport—a narrow tunnel that became known as the Tunnel of Hope. Measuring only about 5 feet high and 3 feet wide, this cramped passage allowed food, medicine, weapons, and people to move unseen between the besieged city and free territory.

For nearly four years, this tunnel sustained urban life during one of modern history’s longest sieges. The tunnel wasn’t comfortable—people crawled through mud and water in near-total darkness, sometimes waiting hours for their turn to pass through.

But it was hope made physical, proof that the city wouldn’t be starved into submission. Families sent children through to safety, while resistance fighters brought supplies back in.

The tunnel became Sarajevo’s umbilical cord, keeping the city alive when everything above ground was targeted by snipers and artillery. Today, part of the tunnel is preserved as a museum, and walking through it is intensely emotional.

You can see where desperate hands clawed at earth, where makeshift lights once hung, where thousands passed through in fear and hope. It’s not an ancient wonder like Derinkuyu—it’s a raw, recent reminder that people still build underground cities when survival demands it, proving that the human instinct to dig deep during danger remains as strong as ever.

Subterranean Shelters of Cappadocia — Turkey

Smaller sites like Gaziemir, Özlüce, and Tatlarin dot the Cappadocian landscape, each revealing how pervasive underground living was across central Anatolia. These aren’t tourist hotspots like Derinkuyu, but they’re equally fascinating examples of how entire communities carved homes, storage areas, and communal spaces into volcanic rock.

Families lived here for generations, creating cozy underground neighborhoods that sheltered them from countless invasions and conflicts. What I love about these lesser-known sites is their intimacy.

Without crowds of tourists, you can really imagine daily life—children playing in carved rooms, families gathering for meals, neighbors chatting in tunnel intersections. The spaces feel more human-scaled than the massive cities, with personal touches like niches carved for oil lamps or small alcoves that might have held family treasures.

These were homes, not just shelters. The sheer number of these sites proves that underground living wasn’t exceptional in ancient Cappadocia—it was normal.

Nearly every village had its own subterranean component, creating a regional culture comfortable with spending significant time below ground. The volcanic rock made digging relatively easy, and the strategic advantages were obvious: invaders couldn’t burn what they couldn’t see.

These smaller shelters show us that underground cities existed on every scale, from massive urban complexes to family-sized hideouts, all serving the same purpose—keeping communities safe and together.