American history textbooks love the highlight reel but they often leave out the parts that explain why the country is the way it is. Whole communities get reduced to side notes, while the most defining fights, ideas, and wins are treated like optional reading.

These 17 books bring those missing chapters back – clear, unflinching, and deeply human – so you can finally see the full story that was always there.

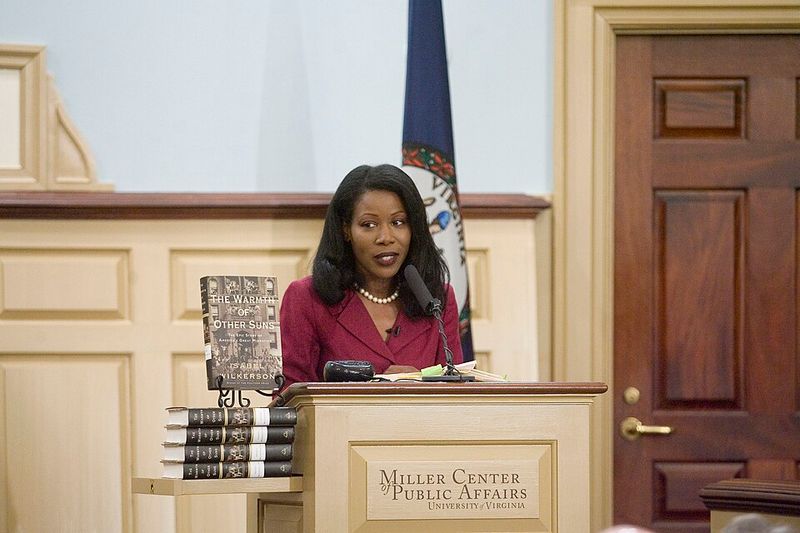

1. The Warmth of Other Suns (Isabel Wilkerson) – the migration that reshaped modern America

Six million people packed their lives into suitcases and left the South between 1915 and 1970. Wilkerson follows three of them through their personal journeys north and west, tracking how their decisions rippled through American cities.

The book reads like a novel but lands with the weight of serious history. You meet Ida Mae Gladney, George Starling, and Robert Foster as real people making impossible choices.

Their stories show how the Great Migration wasn’t just movement – it was revolution.

Cities like Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles became what they are today because of these migrants. They brought jazz, new voting blocs, labor power, and cultural energy that redefined urban America.

Wilkerson connects individual courage to massive social change.

Reading this book changed how I see highway systems, neighborhood boundaries, and even music history. Everything connects back to those train tickets and bus rides.

The warmth they sought wasn’t just climate – it was freedom, dignity, and possibility that the South refused to give them.

2. Stamped from the Beginning (Ibram X. Kendi) – a deep history of racist ideas in the U.S.

Racist ideas didn’t just happen. Someone invented them, refined them, and sold them to the public as truth.

Kendi traces five centuries of this intellectual crime, showing exactly who benefited and how the lies evolved.

This National Book Award winner moves through American history by following five major figures, from Cotton Mather to Angela Davis. Each era gets its own racist logic examined and dismantled.

The book proves that ignorance never drove racism – self-interest did.

Kendi divides historical figures into segregationists, assimilationists, and antiracists. That framework helps you spot the patterns in how people justified inequality across completely different time periods.

The arguments change but the function stays the same.

What hits hardest is realizing how many “progressive” thinkers still promoted racist ideas while claiming to help. The book doesn’t let anyone off easy.

It’s dense and challenging, but it rewires how you read history, news, and even casual conversations about race in America today.

3. Before the Mayflower (Lerone Bennett Jr.) – Black history before ‘the beginning’ we’re taught

The American story doesn’t start in 1620. Bennett opens centuries earlier, showing Black presence in the Americas long before Plymouth Rock became a tourist site.

That reframing alone shifts everything.

Originally published in 1962, this book still holds up as a comprehensive counter-narrative to sanitized textbooks. Bennett was an editor at Ebony magazine and wrote with clarity that makes complex history accessible.

He covers slavery, resistance, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow with equal depth.

What makes this essential is how it refuses to treat Black history as a side plot. Bennett centers African Americans in the full sweep of American development – economic, political, cultural.

The book proves that you can’t understand this country without understanding Black struggle and achievement.

I picked this up expecting a dry historical text and got something closer to a revelation. The chapter on Black soldiers in the Revolutionary War alone rewrites what most of us learned in school.

Bennett doesn’t just add footnotes to history – he demands we rewrite the whole narrative with honesty.

4. Parting the Waters (Taylor Branch) – the Civil Rights Movement in full scale

Branch spent years reconstructing the Civil Rights Movement with the kind of detail usually reserved for presidential biographies. This first volume of his trilogy covers 1954 to 1963, the years that transformed America through organized resistance and moral courage.

Martin Luther King Jr. emerges here as a real person – brilliant, flawed, exhausted, strategic. Branch doesn’t worship or tear down; he reports with nuance.

You see the movement’s internal debates, the role of women who rarely got credit, and the constant danger everyone faced.

The book won the Pulitzer Prize for good reason. Branch makes you feel the weight of each decision, each march, each act of nonviolent resistance.

He shows how ordinary people became heroes by showing up when it mattered most.

What surprised me most was learning how much planning went into “spontaneous” protests. The movement was strategic, disciplined, and deeply thoughtful.

Parting the Waters proves that social change doesn’t just happen. It gets organized, funded, and fought for by people willing to risk everything for a better future.

5. Eyes on the Prize (Juan Williams) – the movement’s defining battles, told through people

Williams wrote this as a companion to the legendary documentary series, but the book stands alone as essential reading. It covers 1954 to 1985, tracking the movement from Brown v.

Board of Education through the rise of Black political power.

The strength here is how Williams centers ordinary people alongside famous leaders. You meet students who integrated schools, workers who organized boycotts, and families who opened their homes to activists.

Their testimonies make history immediate and personal.

Each chapter tackles a major event – Little Rock, Freedom Rides, Selma, the rise of Black Power. Williams doesn’t smooth over conflicts within the movement or pretend everyone agreed on tactics.

The honesty makes the victories more remarkable and the setbacks more instructive.

I remember watching the documentary in school and feeling moved but distant. Reading the book years later hit differently.

Williams gives you enough context to understand why each battle mattered and how each win or loss shaped what came next. Eyes on the Prize reminds us that progress isn’t inevitable—it’s fought for, inch by inch.

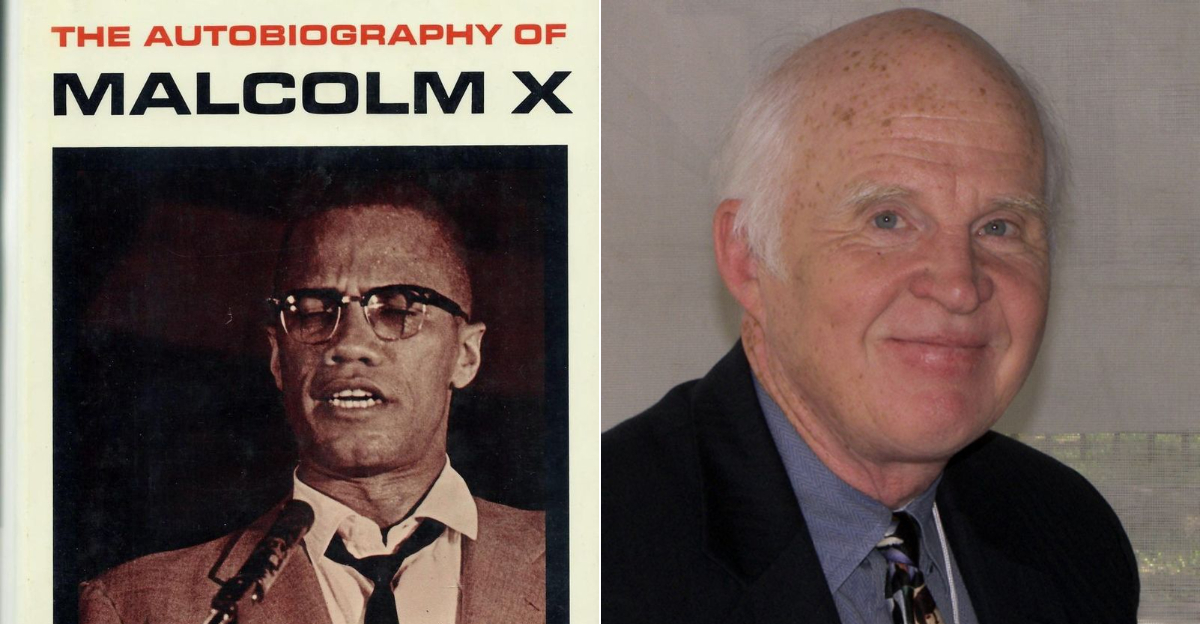

6. The Autobiography of Malcolm X (Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley) — transformation as testimony

Malcolm X’s life story reads like several lifetimes compressed into 39 years. From street hustler to Nation of Islam minister to Pan-African internationalist, his journey maps the complexity of Black identity in mid-century America.

Haley’s collaboration with Malcolm produced something rare: a political autobiography that’s also deeply personal and brutally honest. Malcolm doesn’t hide his mistakes or soften his earlier positions.

He shows you his thinking as it evolved, right up until his assassination.

The book challenges comfortable narratives about the Civil Rights Movement. Malcolm’s critique of nonviolence, his emphasis on self-defense, and his analysis of systemic racism still spark debate decades later.

He refused to beg for rights that should have been guaranteed.

What stays with you is Malcolm’s hunger for knowledge and his willingness to change his mind based on new information. His pilgrimage to Mecca shifted his understanding of race and solidarity.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X proves that growth and transformation are always possible, even when the world tries to lock you into one identity.

7. Freedom Is a Constant Struggle (Angela Y. Davis) – linking past liberation fights to the present

Davis has spent decades connecting dots that others miss or ignore. This collection of essays and interviews links Black freedom struggles to Palestinian liberation, prison abolition to feminism, historical resistance to current movements.

Her analysis cuts through simplistic narratives about progress. Davis argues that liberation is never won once and for all.

It requires constant vigilance and solidarity across movements. She sees patterns in how power operates and how people resist.

The book came out during the rise of Black Lives Matter and speaks directly to that moment while drawing on centuries of struggle. Davis doesn’t just theorize.

She’s been an activist since the 1960s, including time as a political prisoner. Her perspective carries weight earned through lived experience.

Reading Davis feels like getting a master class in how to think about justice globally. She refuses to let anyone treat racism as purely an American problem or separate it from capitalism and imperialism.

Freedom Is a Constant Struggle reminds us that our fights are connected and our solidarity must be too.

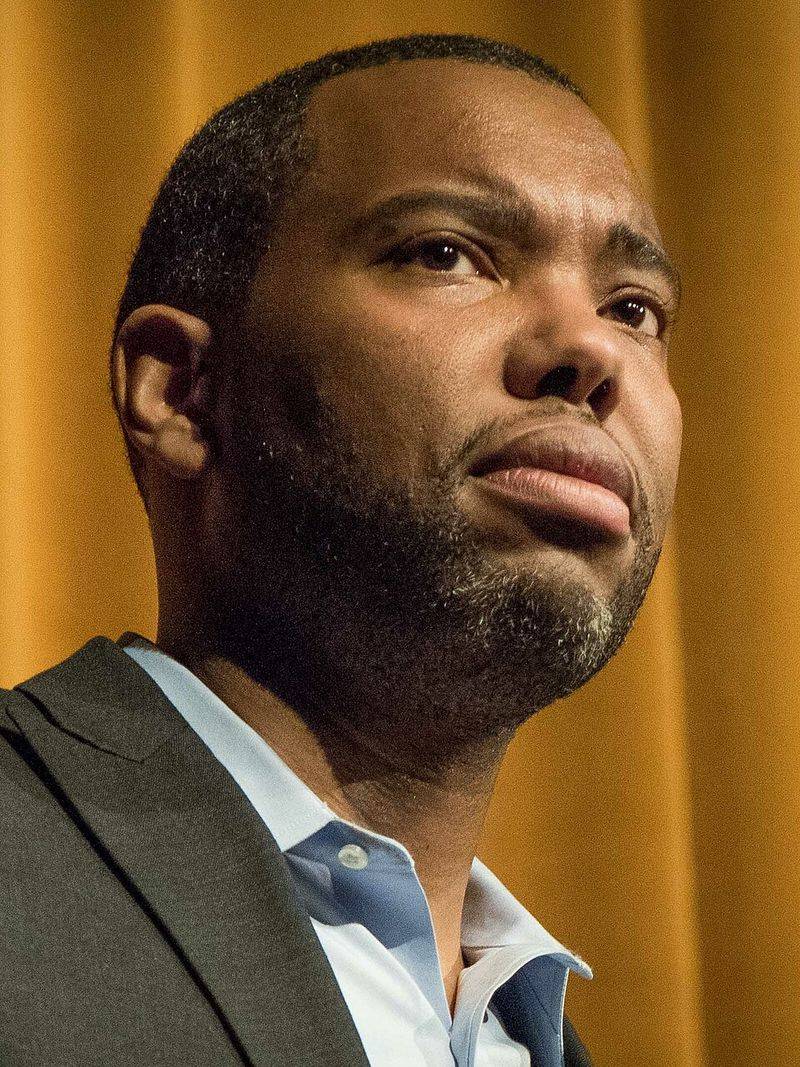

8. Between the World and Me (Ta-Nehisi Coates) – a letter that hits like a reckoning

Coates wrote this as a letter to his teenage son about living in a Black body in America. That framing makes the book intimate and urgent.

You’re reading over someone’s shoulder as a father tries to prepare his child for a dangerous world.

The prose is sharp and beautiful, never wasting a word. Coates draws on personal experience, history, and cultural analysis to explain how America was built on the destruction of Black bodies.

He doesn’t offer hope or redemption, he offers truth.

The book won the National Book Award and became required reading for anyone trying to understand contemporary conversations about race. Coates refuses to comfort white readers or promise that things will get better.

He demands that people face what America actually is, not what it claims to be.

I read this in one sitting and then sat with it for days. Coates articulates feelings I’d had but couldn’t name about vulnerability, fear, and the exhaustion of constant vigilance.

Between the World and Me is a gift to his son and a challenge to the rest of us.

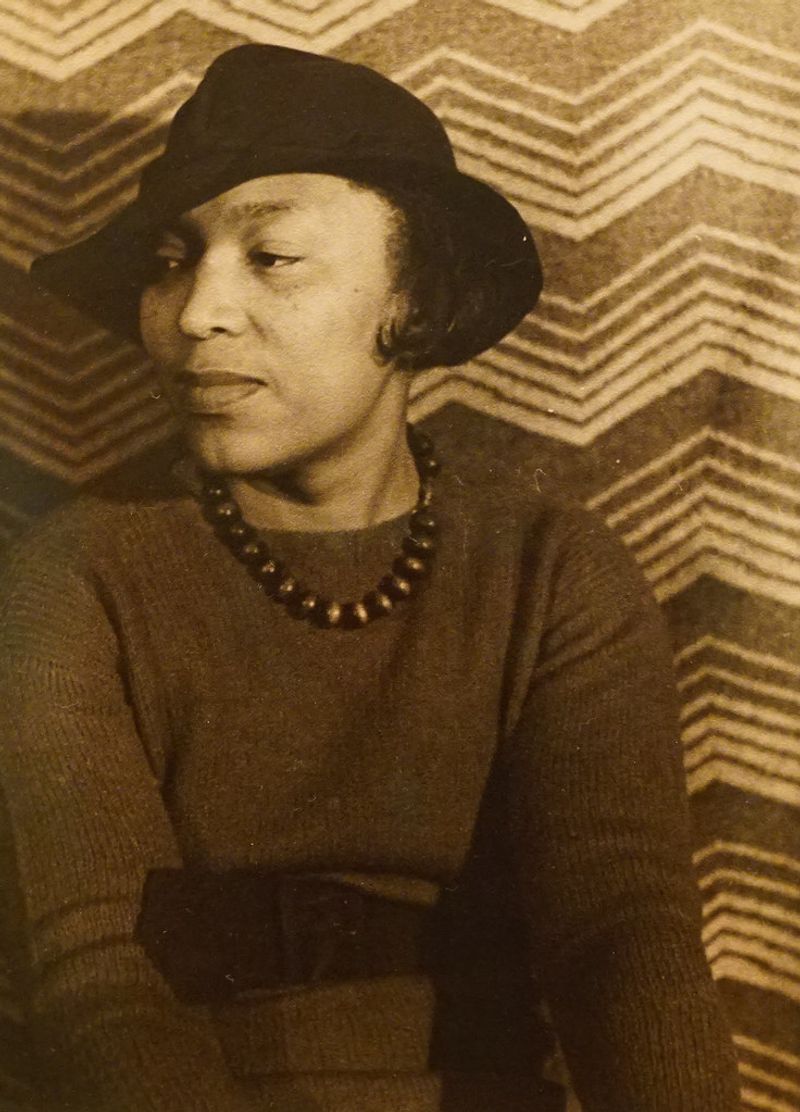

9. Barracoon (Zora Neale Hurston) – a direct voice from the transatlantic slave trade

In 1927, Hurston interviewed Oluale Kossola, known as Cudjo Lewis, one of the last known survivors of the transatlantic slave trade. He was kidnapped from West Africa as a young man and brought to Alabama illegally in 1860, decades after the trade was banned.

Hurston transcribed his story in his own dialect, preserving his voice exactly as he spoke it. That choice was controversial but crucial – Cudjo’s words carry power that sanitized translation would have stolen.

You hear his pain, his longing for home, his survival.

The manuscript sat unpublished for decades because publishers wanted Hurston to change Cudjo’s speech. She refused.

The book finally came out in 2018, giving readers access to testimony that’s both historically invaluable and emotionally devastating.

Barracoon puts a human face on the Middle Passage in a way statistics never can. Cudjo talks about his family, his capture, the horror of the ship, and his life in America.

His story reminds us that slavery wasn’t ancient history, people who lived through it were alive within living memory.

10. Heavy (Kiese Laymon) – memoir that refuses easy answers

Laymon writes to his mother about growing up Black, Southern, and struggling with his body in a country that polices Black bodies constantly. The book is unflinching about family trauma, eating disorders, and the pressure to perform respectability.

Heavy is literary without being pretentious, personal without being self-indulgent. Laymon examines his relationship with his brilliant, complicated mother and how her expectations shaped him.

He talks about weight, desire, shame, and survival with raw honesty.

The memoir won multiple awards and critical acclaim for its refusal to provide tidy resolutions. Laymon doesn’t wrap up his story with lessons learned or redemption achieved.

He shows you the ongoing work of being human under impossible conditions.

What makes this book essential is how Laymon connects personal struggle to systemic violence. His eating disorder isn’t just individual psychology.

It’s a response to living in a body that America treats as threatening. Heavy proves that the personal is always political, especially for Black Americans navigating a hostile world.

11. The New Jim Crow (Michelle Alexander) – mass incarceration as a system

Alexander argues that mass incarceration functions as a racial caste system disguised as criminal justice. The book traces how the War on Drugs targeted Black communities deliberately, creating a pipeline from schools to prisons that devastates families and communities.

The statistics are staggering and the legal analysis is thorough. Alexander shows how felon disenfranchisement, employment discrimination, and housing restrictions create a permanent underclass.

Once you’re labeled a felon, you lose access to the building blocks of a stable life.

The New Jim Crow became hugely influential in criminal justice reform conversations. Alexander doesn’t just critique, she connects current policies to historical segregation, showing how systems adapt to maintain racial hierarchy even after explicit racism becomes illegal.

This book made me rethink everything I thought I knew about crime, punishment, and fairness. Alexander proves that you can’t address mass incarceration without addressing racism, and you can’t claim America is post-racial while locking up Black men at rates that would shock earlier generations.

The system isn’t broken, it’s working exactly as designed.

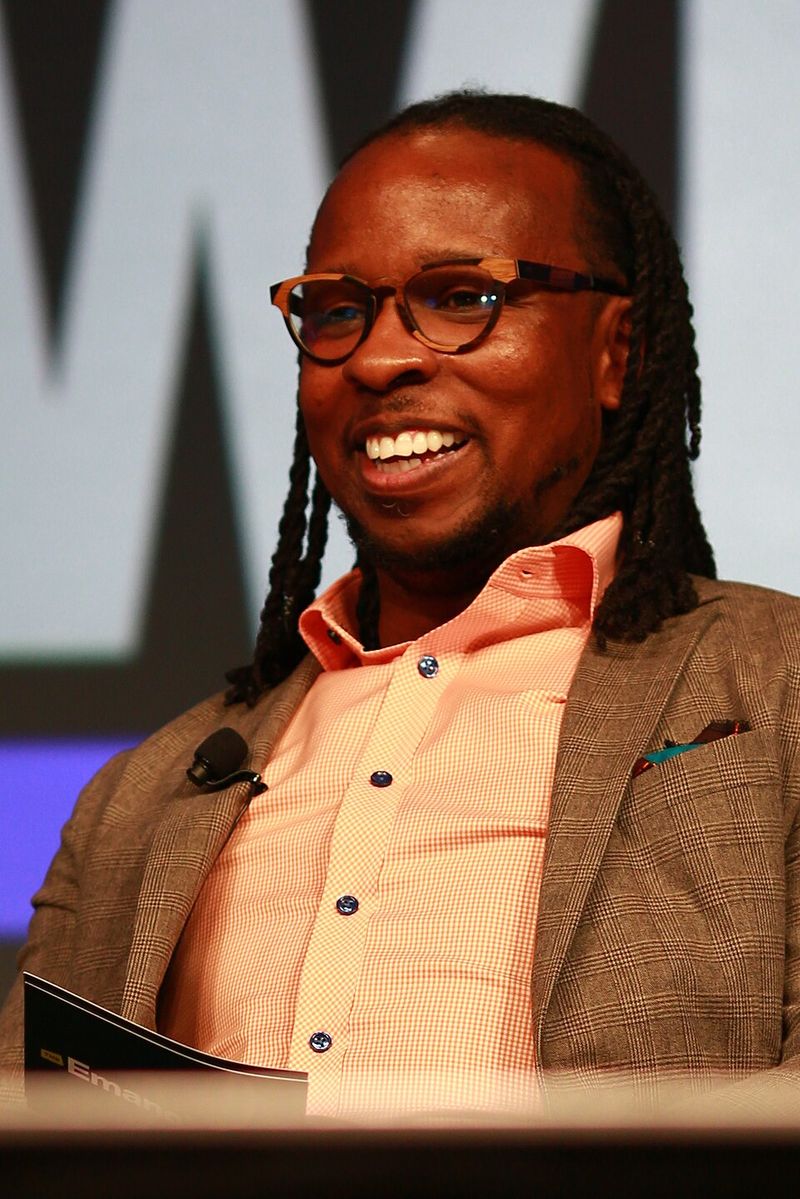

12. How to Be an Antiracist (Ibram X. Kendi) – a framework built for action

Kendi rejects the idea that “not being racist” is enough. He argues that you’re either actively working against racist policies and ideas, or you’re passively allowing them to continue.

There’s no neutral position when systems are already rigged.

The book mixes memoir with argument, showing how Kendi himself held racist ideas even while experiencing racism. He defines terms clearly: racist policies create racial inequity, and racist ideas justify those policies.

Change the policies, and you change outcomes.

How to Be an Antiracist gives readers concrete ways to examine their own beliefs and actions. Kendi provides a framework for identifying racism in everything from education to healthcare to criminal justice.

The book is designed to make people uncomfortable and then give them tools to do something about it.

What I appreciate most is Kendi’s refusal to let anyone feel smug or finished. Being antiracist is an ongoing practice, not an identity you achieve once.

You’ll make mistakes, hold contradictions, and have to keep learning. The book challenges readers to move from defensiveness to action.

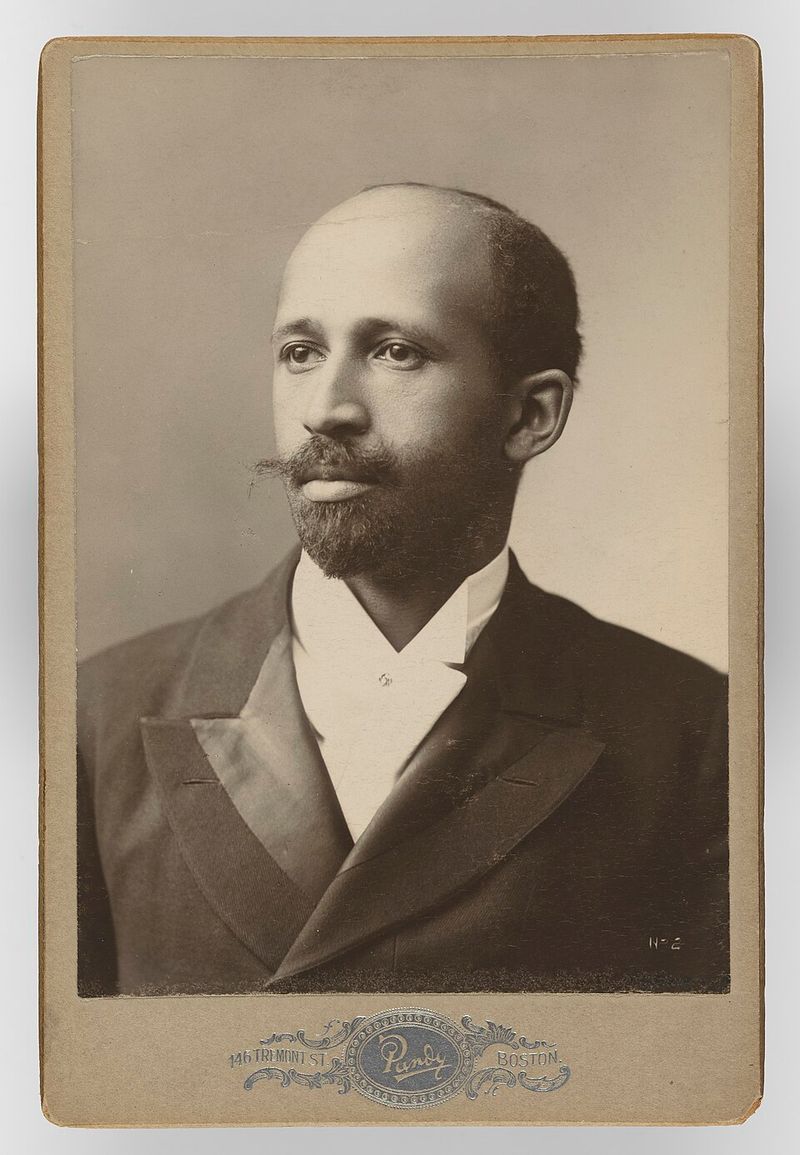

13. Black Reconstruction in America (W.E.B. Du Bois) – Reconstruction rewritten, properly

Du Bois published this in 1935, directly challenging the racist historical narrative that portrayed Reconstruction as a failure caused by Black incompetence. He argued the opposite: Reconstruction was a brief period of multiracial democracy that terrified white supremacists into violent backlash.

The book examines the role of Black workers and soldiers in ending slavery and building new political systems. Du Bois shows how formerly enslaved people organized, voted, held office, and pushed for education and land reform.

Their political agency was remarkable and deliberately erased from history.

Black Reconstruction is dense and scholarly, but it’s also passionate and angry. Du Bois understood that history gets written by winners, and he refused to let lies stand.

His work laid groundwork for later historians to reexamine Reconstruction honestly.

Reading this reminds you how much of what we’re taught is propaganda. The “Lost Cause” narrative dominated textbooks for generations, teaching children that slavery was benign and Black people weren’t ready for freedom.

Du Bois demolished those lies with evidence and moral clarity that still resonates today.

14. Beloved (Toni Morrison) – the haunting that history leaves behind

Morrison based this novel on the true story of Margaret Garner, an enslaved woman who killed her daughter rather than see her returned to slavery. The book explores that impossible choice and its aftermath through Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman haunted by her past.

Beloved is the ghost, both literal and metaphorical, of slavery’s trauma. Morrison’s prose is poetic and devastating, moving between past and present to show how violence echoes through generations.

The novel refuses to let readers look away from slavery’s psychological horror.

The book won the Pulitzer Prize and Morrison later won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Beloved is taught in schools and universities worldwide as a masterpiece of American literature.

It’s also deeply challenging, demanding emotional investment and careful reading.

I’ll be honest, this book broke me open. Morrison doesn’t offer comfort or easy catharsis.

She shows how trauma lives in the body, how love and violence get tangled, how freedom doesn’t erase what was done. Beloved proves that some wounds don’t heal, they just become part of who we are.

15. The Fire Next Time (James Baldwin) – essays that still read like tomorrow’s headlines

Baldwin wrote these two essays in 1963, but they could have been published yesterday. He examines race, religion, and American identity with prose so sharp and beautiful it feels like revelation.

Every sentence carries weight.

The first essay is a letter to his nephew on the hundredth anniversary of emancipation. Baldwin tells him that white Americans are trapped by their own lies about race, and that Black people must refuse to accept those lies.

The second essay explores Baldwin’s time in the church and his meetings with Elijah Muhammad.

What makes Baldwin essential is his moral clarity combined with deep empathy. He understands why white Americans cling to racism.

It protects them from facing their own history and humanity. But understanding doesn’t mean accepting.

Baldwin demands that America reckon with its sins.

The Fire Next Time changed how I read and write. Baldwin proves that moral argument can be art, that essays can carry the power of prophecy.

His warning still stands: America must face its racial reality or burn in the fire of its own making.

16. Their Eyes Were Watching God (Zora Neale Hurston) – a classic of voice, love, and selfhood

Janie Crawford refuses to live the life others choose for her. Hurston’s 1937 novel follows Janie through three marriages and a journey toward self-determination that was radical for its time and remains powerful today.

The book celebrates Black Southern dialect and culture at a time when many writers were trying to prove Black sophistication through formal language. Hurston insisted that Black vernacular was beautiful and worthy of literature.

Her choice influenced generations of writers.

Their Eyes Were Watching God wasn’t initially successful. Some critics dismissed it as too focused on love and not political enough.

Alice Walker later championed the book, helping it become recognized as a landmark of American literature. Now it’s taught everywhere.

What makes this novel endure is Janie’s voice and her determination to define herself. She wants love but refuses to shrink herself to get it.

Hurston writes about desire, autonomy, and the cost of choosing yourself with honesty that still feels fresh. Their Eyes Were Watching God proves that personal freedom is always political, especially for Black women.