Most history textbooks spotlight the same handful of places when telling Black American stories. But scattered across the country are dozens of sites where real freedom was won, communities were built from scratch, and movements began that changed everything.

These places don’t always get the recognition they deserve, even though they’re just as important as the famous monuments everyone knows. From a Florida fort that offered freedom before America was even a country to an Oakland storefront that launched a revolution, these 17 landmarks tell stories that deserve to be heard.

Fort Mose, Florida – Freedom’s First Address

In 1738, enslaved people risked everything to reach a place that promises actual freedom. Fort Mose became that beacon decades before the Revolutionary War even started.

Spanish authorities established it near St. Augustine as the first legally sanctioned free Black settlement in what would become the United States.

The fort’s residents weren’t just free in name. They built homes, farmed land, and defended their community against British attacks.

Men served in the Spanish militia, protecting both their new home and St. Augustine itself.

Today, Fort Mose is mostly gone, claimed by time and coastal erosion. But the site has a visitor center that tells these incredible stories.

Walking the grounds, you can almost feel the weight of those decisions people made centuries ago.

What makes Fort Mose so powerful is its timing. While most American colonies were doubling down on slavery, this small outpost was proving freedom could work.

The people who found refuge here weren’t waiting for history to change. They were making it happen themselves, one brave escape at a time.

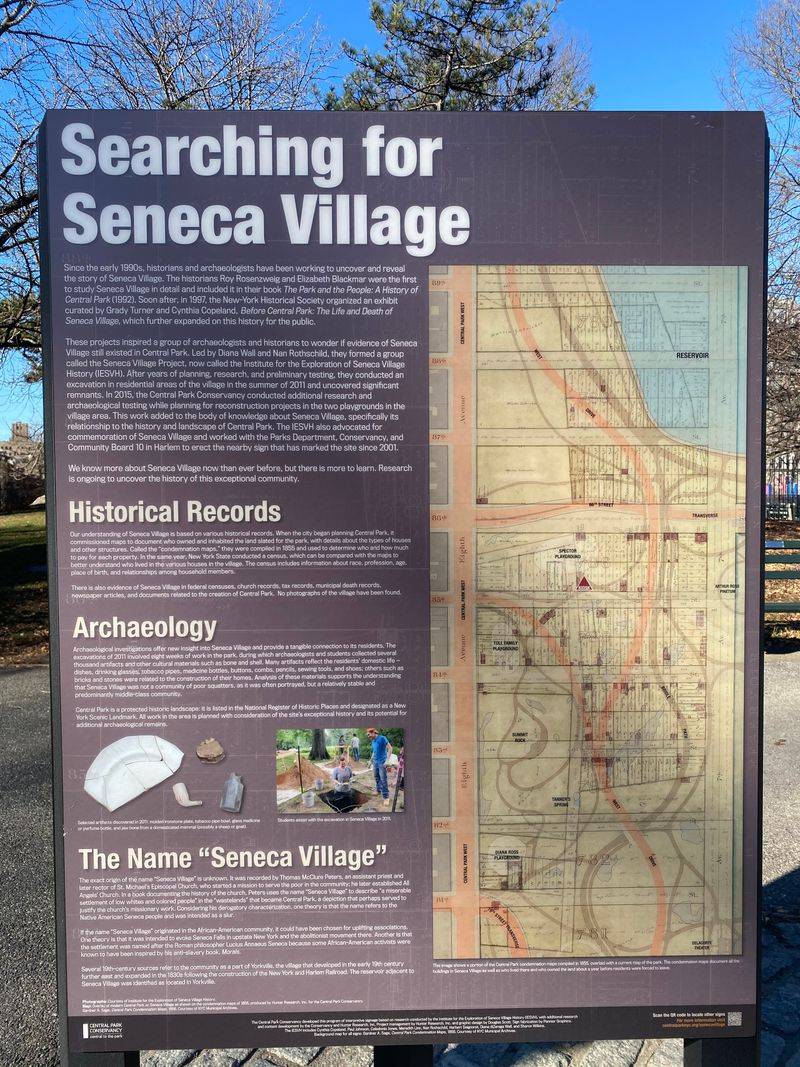

Seneca Village, New York City – The Neighborhood Central Park Erased

Central Park looks like it’s always been there, right? Wrong.

Before Frederick Law Olmsted designed those famous pathways, a thriving community called Seneca Village occupied the land. Founded in 1825, it was home to property-owning Black families who built churches, schools, and lives.

Owning property was huge. At a time when most Black New Yorkers couldn’t vote (property requirements blocked them), Seneca Village residents had that power.

They weren’t just surviving—they were prospering in a city that made that incredibly difficult.

Then came 1857. The city used eminent domain to seize the land for park construction.

Families were forced out, their homes demolished. For over a century, Seneca Village was nearly forgotten, buried under baseball fields and walking paths.

Archaeologists rediscovered the site in the 1990s, unearthing foundations, pottery, and personal items. Now there are markers in the park acknowledging what stood there before.

It’s a reminder that progress for some often meant erasure for others, and that every piece of land has stories worth remembering.

John Brown’s Fort, Harpers Ferry, West Virginia – The Spark That Lit Everything

Sometimes a tiny building holds enormous history. This engine house at Harpers Ferry looks almost too small to matter, but it’s where John Brown made his desperate last stand in 1859.

His raid on the federal armory was supposed to arm enslaved people for rebellion. It failed spectacularly.

Brown and his followers, including several Black men, held out in this building for 36 hours before Marines led by Robert E. Lee stormed it.

Brown was captured, tried, and hanged. But his actions sent shockwaves through a nation already splitting apart.

Southerners saw Brown as a terrorist. Abolitionists saw him as a martyr.

Both sides knew something fundamental had shifted. The raid made compromise feel impossible and pushed the country closer to war.

The fort itself has moved twice since 1859, but it’s back near its original spot now. Standing inside, you can see bullet holes in the walls.

It’s cramped and dark, exactly the kind of place where desperate men make history-changing decisions, even when they know they won’t survive them.

Whitney Plantation, Louisiana – Where Truth Replaces Romance

Most plantation tours sell you mint juleps and mansion fantasies. Whitney Plantation does something different—it tells the truth.

Opened as a museum in 2014, this site focuses entirely on the enslaved people who lived and died there, not the white families who profited from their labor.

The exhibits are powerful and uncomfortable. You’ll see slave quarters, read first-person accounts, and walk past memorial walls listing thousands of names.

There’s a sculpture garden featuring children’s figures, representing the kids who were born into bondage.

This approach is rare. Too many historic sites still romanticize the “Old South,” glossing over the brutal reality of slavery.

Whitney refuses to do that. Every tour, every display, every word centers the humanity of enslaved people.

Visiting Whitney isn’t fun in the traditional sense. It’s heavy, emotional, and necessary.

The plantation’s owners deliberately chose this path, knowing it would challenge visitors and contradict decades of Lost Cause mythology. That choice matters.

It’s a corrective to all those other tours that treat slavery as a footnote to architecture.

Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park, California – Freedom’s California Dream

California had its own chapter in Black self-determination, and Allensworth was it. Founded in 1908 by Lieutenant Colonel Allen Allensworth, a formerly enslaved man who became the Army’s highest-ranking Black officer, this town was built by and for African Americans.

No compromises, no white oversight—just Black people building their own future.

The town had everything: schools, churches, a library, farms. Residents governed themselves and made their own rules.

For a while, Allensworth thrived, proving that Black communities could succeed when given the chance.

Then water problems and railroad route changes strangled the town’s economy. By the 1970s, Allensworth was nearly abandoned.

But California recognized its importance and established it as a state historic park in 1976.

Today, you can walk through restored buildings and imagine what life was like when this experiment in self-governance was alive. Allensworth represents hope, resilience, and the dream of controlling your own destiny.

It’s a reminder that Black excellence didn’t just happen in cities. It happened in small California towns where people dared to build something entirely their own.

African Burial Ground National Monument, New York City – Manhattan’s Hidden Cemetery

Construction workers in 1991 weren’t expecting to find a massive cemetery in downtown Manhattan. But that’s exactly what happened.

The African Burial Ground revealed thousands of burials from the 1600s and 1700s, both free and enslaved Africans who built colonial New York.

The discovery rewrote the city’s history. Historians knew Black people lived in early New York, but the burial ground’s size shocked everyone.

Up to 15,000 people might be buried there, making it one of the largest colonial-era African cemeteries ever found.

The remains showed evidence of brutal labor and poor living conditions. Some skeletons bore marks of violence.

But archaeologists also found signs of African burial traditions, showing how people maintained their culture despite enslavement.

After years of debate, the site became a national monument in 2006. There’s now a memorial and visitor center telling these stories.

Walking through it, you realize how much history gets paved over—literally. These people built New York, and for centuries, the city forgot they existed.

Now, finally, they’re remembered.

Nicodemus National Historic Site, Kansas – Starting Over on the Frontier

After the Civil War, thousands of formerly enslaved people headed west in what became known as the Exoduster movement. They wanted land, freedom, and a chance to start fresh.

Nicodemus, Kansas, founded in 1877, became one of those fresh starts—and the only one that’s survived.

The first settlers arrived to find nothing but prairie. No buildings, no infrastructure, just land and possibility.

They dug homes into hillsides and slowly built a town. Within a few years, Nicodemus had businesses, schools, churches, and baseball teams.

Life wasn’t easy. Droughts, economic downturns, and isolation took their toll.

Many residents eventually left, but some families stayed, determined to preserve what their ancestors built.

Now the National Park Service maintains Nicodemus as a historic site. You can visit the remaining buildings and hear stories from descendants who still live there.

It’s a powerful reminder that Black history isn’t just Southern history. It’s Western history too, written by people who refused to let slavery define their entire lives.

They went west seeking freedom, and in Nicodemus, they found it.

Camp Nelson National Monument, Kentucky – Where Enlistment Meant Liberation

Joining the Union Army was risky if you were Black and enslaved in a border state like Kentucky. But Camp Nelson made that risk worth taking.

Established as a supply depot, it became one of the most important USCT recruitment and training centers. Over 10,000 Black men enlisted there.

Enlistment brought freedom—not just for the soldiers, but eventually for their families too. Refugee camps at Nelson housed wives, children, and relatives who fled enslavement when their men joined up.

It was messy, overcrowded, and sometimes tragic (many died from disease), but it represented hope.

The camp’s commander initially tried to expel refugee families during winter 1864, leading to deaths from exposure. Public outcry forced policy changes, and the camp became a more permanent haven.

By war’s end, it was a thriving community.

Camp Nelson became a national monument in 2018. The preserved earthworks and interpretive center tell stories of men who fought for their freedom and families who risked everything to claim it.

It’s a place where military history and freedom struggles intersect, showing how war became a pathway to liberation.

Penn Center, St. Helena Island, South Carolina – The School That Built a Movement

Penn Center started as a school in 1862, right in the middle of the Civil War. Northern abolitionists came to the Sea Islands to teach formerly enslaved people who’d been freed when Union forces captured the area.

It was one of the first schools for freed people in the South.

But Penn Center became way more than a school. It evolved into a community hub, preserving Gullah culture and providing education for generations.

During the Civil Rights Movement, it hosted planning meetings—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited multiple times to strategize in a safe space away from mainland threats.

The center’s longevity is remarkable. While many Reconstruction-era institutions failed, Penn Center adapted and survived.

It became a model for Black education and community organizing across the South.

Today, Penn Center operates as a museum and cultural center. You can tour historic buildings, learn about Gullah heritage, and understand how one school helped shape both Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement.

It’s a place where education and activism merged, proving that teaching people to read was always about more than just literacy.

Mother Bethel AME Church, Philadelphia – Where a Movement Began

Richard Allen got tired of being told where to sit. In 1787, he and other Black worshippers walked out of a white Methodist church that tried to segregate them during prayer.

That walkout led to Mother Bethel AME Church, founded in 1794 and still standing on the same spot today.

This wasn’t just another church. It became the birthplace of the AME denomination, one of the largest and most influential Black religious institutions in America.

Allen’s vision was simple: Black people deserved to worship without humiliation.

Mother Bethel was also a Underground Railroad station. Its basement hid freedom seekers heading north, adding resistance to its spiritual mission.

The church combined faith and activism long before that became common.

You can still attend services at Mother Bethel. The building itself is the oldest piece of land continuously owned by African Americans in the United States.

Walking inside connects you to centuries of Black faith, resilience, and community building. Allen’s decision to walk out and start something new created a legacy that’s lasted over 200 years.

That’s the power of refusing to accept second-class treatment.

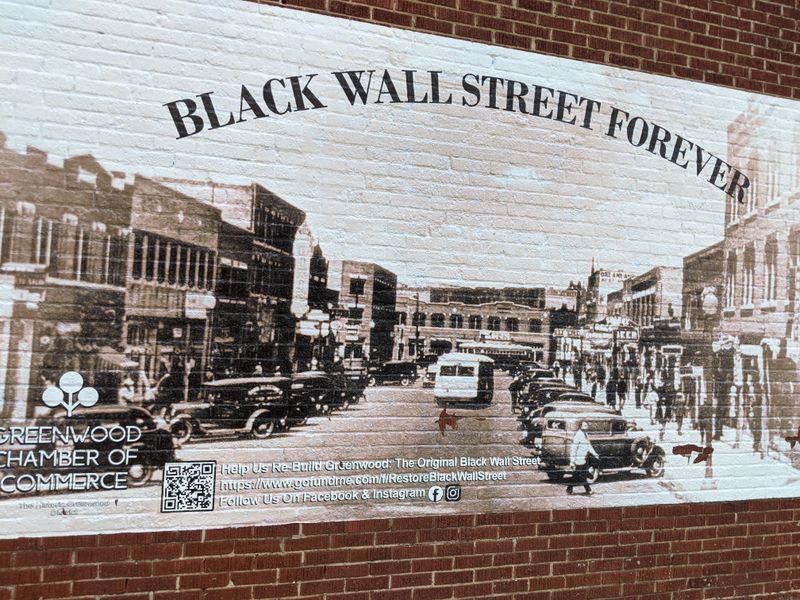

Greenwood (Black Wall Street), Tulsa, Oklahoma – Prosperity and Massacre

Greenwood was thriving. By 1921, this Tulsa neighborhood had become so prosperous that people called it Black Wall Street.

Black-owned businesses lined the streets—hotels, theaters, newspapers, grocery stores. Wealth circulated within the community, creating generational prosperity.

Then came the massacre. Over two days in June 1921, white mobs attacked Greenwood, burning it to the ground.

Planes dropped incendiary devices. Hundreds died (exact numbers remain disputed).

Thousands were left homeless. An entire community was destroyed.

For decades, Tulsa tried to forget. The massacre wasn’t taught in schools, wasn’t discussed publicly.

Survivors were silenced, their trauma ignored. Only recently has the full horror been acknowledged and studied.

Today, Greenwood is rebuilding, and institutions like the Greenwood Rising History Center tell the story that was suppressed for so long. Walking through the neighborhood, you see both what was lost and what’s being reclaimed.

It’s a reminder that Black prosperity has always threatened those invested in white supremacy. Greenwood wasn’t destroyed because it was failing.

It was destroyed because it was succeeding. That truth matters now more than ever.

Fort Monroe / Old Point Comfort, Virginia – Where Slavery Began and Freedom Found Policy

August 1619. A ship arrived at Old Point Comfort carrying the first Africans to English Virginia.

They weren’t technically slaves yet—the legal framework for that horror came later. But their arrival marked the beginning of a system that would define American history for centuries.

Fast forward to 1861. Fort Monroe, built on that same land, became a refuge during the Civil War.

When three enslaved men escaped there seeking freedom, General Benjamin Butler made a brilliant legal argument: they were “contraband of war,” property that shouldn’t be returned to enemies. That decision created a loophole that freed thousands.

The fort’s dual history is almost too symbolic. The place where slavery effectively began in English America became a place where escape became policy.

Thousands of freedom seekers flooded to Fort Monroe, overwhelming the army but forcing the Union to confront slavery directly.

Today, Fort Monroe is a national monument. You can walk the same grounds where both stories unfolded.

It’s a powerful reminder that history isn’t simple. Places can hold multiple meanings, and endings can grow from beginnings in unexpected ways.

The Robert Smalls House, Beaufort, South Carolina – From Enslaved to Congressman

Robert Smalls pulled off one of the Civil War’s most daring escapes. In 1862, while enslaved and working as a pilot, he commandeered the CSS Planter, a Confederate ship, sailed it past multiple forts, and delivered it to Union forces.

He freed himself, his family, and several others in one brilliant move.

But Smalls didn’t stop there. He became a Union Navy captain, then a businessman, then a U.S.

Congressman during Reconstruction. He bought the very house in Beaufort where he’d been enslaved, turning his former master’s home into his own residence.

That house still stands, though it’s privately owned and not open for tours. But its existence tells a story of transformation.

Smalls went from property to property owner, from enslaved to legislator, from powerless to powerful.

His life demonstrates what was possible during Reconstruction when Black men gained political rights. Smalls fought for education, civil rights, and economic opportunity.

His career ended when white supremacists violently reclaimed Southern governments, but his legacy endured. The house is a symbol of what he achieved and what could have been if Reconstruction hadn’t been betrayed.

Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument (IL & MS sites) – Grief That Changed a Nation

Some stories are too painful to tell but too important to ignore. Emmett Till was 14 when he was murdered in Mississippi in 1955, tortured and killed for allegedly whistling at a white woman.

His killers were acquitted by an all-white jury.

Mamie Till-Mobley, Emmett’s mother, made a decision that changed history. She insisted on an open casket funeral, forcing the world to see what racism had done to her son.

Photos of Emmett’s mutilated body appeared in Jet magazine, shocking the nation.

That choice galvanized the Civil Rights Movement. People who’d looked away couldn’t anymore.

Mamie’s grief became activism, her son’s death a catalyst for change. She spent the rest of her life speaking, teaching, and demanding justice.

In 2023, sites in Illinois and Mississippi connected to Emmett’s murder and the trial became a national monument. It’s a recognition that came far too late but matters nonetheless.

The monument ensures future generations will know this story, will understand how violence maintained white supremacy, and will remember Mamie’s courage in making sure her son’s death meant something.

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Kansas City, Missouri – Excellence in the Face of Segregation

Major League Baseball locked Black players out for decades. So they created their own leagues, their own teams, their own excellence.

The Negro Leagues produced some of baseball’s greatest players—Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell—who dominated despite being excluded from the majors.

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, founded in 1990 in Kansas City’s historic 18th & Vine district, preserves that history. It’s not just about baseball.

It’s about Black entrepreneurship, community, and resilience. These leagues were businesses, social institutions, and sources of pride.

When Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, it was a victory for integration but a blow to the Negro Leagues. Black fans started following white teams, and the separate leagues slowly collapsed.

Integration was necessary, but something was lost too.

The museum captures all of that complexity. You’ll see uniforms, equipment, photos, and stories that bring the era to life.

It’s a celebration of talent that was denied its full stage and a reminder that segregation forced Black Americans to create their own institutions—and those institutions were often spectacular.

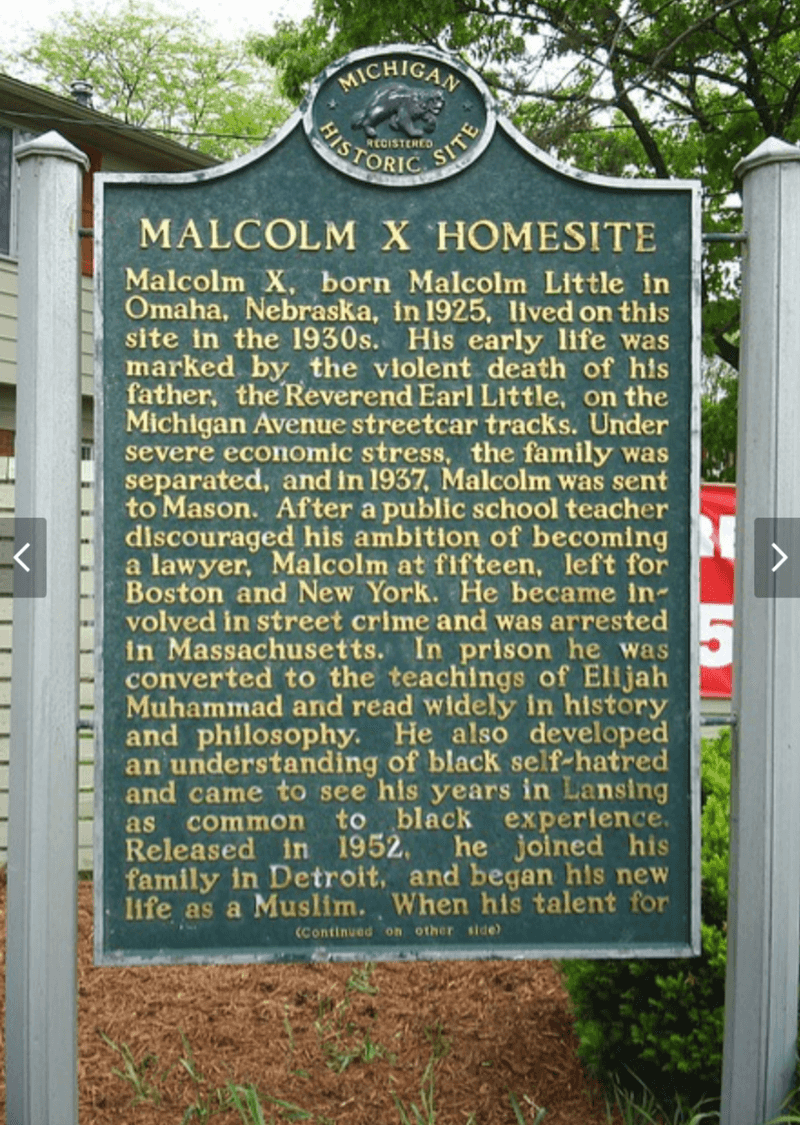

Malcolm X Homesite Marker, Lansing, Michigan – Northern Racism’s Early Lessons

Malcolm X’s childhood in Lansing taught him that racism wasn’t just a Southern problem. The Little family faced constant threats from white supremacist groups.

Their house was burned down when Malcolm was four. His father died under suspicious circumstances that many believe was murder.

These experiences shaped Malcolm’s worldview. He learned early that Northern racism was just as violent as Southern racism, just less honest about it.

Lansing’s white residents didn’t wear hoods, but they still terrorized Black families trying to live decent lives.

The homesite isn’t a museum or major attraction—it’s marked, but understated. Still, it’s an important piece of Malcolm’s story.

Understanding his childhood helps explain his later politics, his anger, his refusal to preach nonviolence to people being violently oppressed.

Malcolm’s Michigan years get less attention than his later activism in New York, but they were foundational. The boy who survived Lansing’s racism became the man who challenged America’s comfortable lies about itself.

That transformation started in Michigan, in a house that no longer exists but whose memory remains powerful.

The Black Panther Party’s First Office, Oakland, California – Revolution From a Storefront

A storefront on Grove Street in Oakland doesn’t look revolutionary. But in 1966, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale opened the Black Panther Party’s first office there, and American politics shifted.

The Panthers combined armed self-defense with community programs—free breakfast for kids, health clinics, education initiatives.

The armed part got all the attention. Panthers openly carrying guns while monitoring police terrified white America and made the group a government target.

But the community programs were just as radical, proving that Black people could organize and meet their own needs.

The party grew rapidly from that Oakland office, establishing chapters nationwide. The FBI’s COINTELPRO program worked to destroy it, using surveillance, infiltration, and violence.

By the mid-1970s, internal conflicts and external pressure had fractured the organization.

The original office is gone now, but the street was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Way, and the Panthers’ legacy lives on. They showed that revolution could mean feeding children and demanding dignity.

They scared the government precisely because they combined militancy with genuine service. That combination—self-defense and community care—remains powerful today, influencing movements that didn’t exist when that Oakland storefront first opened.