Throughout history, a select few have bent entire nations to their will through sheer ego. Their hunger for adoration, control, and legacy ravaged societies and rewrote destinies. These rulers and revolutionaries wielded narcissism like a weapon, cloaking cruelty in spectacle and mythology. Read on to uncover how self-obsession, fused with power, became one of history’s deadliest forces.

Emperor Nero (37–68 CE)

Nero’s reign epitomized the perils of vanity welded to absolute power. The young emperor immersed himself in theatrics, lyre performances, and competitive artistry, demanding applause as policy. After the Great Fire of Rome, he pursued colossal self-glorifying projects, like the Domus Aurea, while scapegoating Christians to deflect blame, unleashing vicious persecutions. Political paranoia fueled betrayals and executions—even his own mother. Nero’s public image pivoted between patron of the arts and capricious tyrant, sustained by flattery and spectacle. He prized adoration above governance, reshaping Rome to mirror his ego. Yet the excess drained coffers and trust, unraveling alliances and inviting revolt. When the Senate declared him an enemy, his theatrical life ended in a final, cowardly act, sealing a legacy of self-obsession over statecraft.

Gaius “Caligula” (12–41 CE)

Caligula’s brief, explosive rule fused cruelty with pageantry, elevating narcissism into state doctrine. Styling himself a living god, he demanded worship, erected temples to his own divinity, and bled the treasury on spectacles. His whims terrified Rome: sudden executions, humiliations of senators, and grotesque extravagance masqueraded as policy. Caligula’s self-deification eroded norms, turning governance into a theater of fear. By enthroning himself above law and tradition, he isolated allies and taunted the Praetorian Guard. Such hubris made his assassins not merely traitors but restorers of balance. Yet his legend endures as a parable of unchecked power. Caligula’s reign demonstrates how megalomania corrodes institutions—swiftly converting an empire’s stability into a stage for one man’s fantasies.

King Henry VIII of England (1491–1547)

Henry VIII’s narcissism redrew England’s spiritual and political map. His break with Rome, driven by the imperative to annul his marriage and secure a male heir, birthed the Church of England and entrenched royal supremacy. Courtly life revolved around his moods, as confidants rose and fell at a nod. Wives, advisors, and rivals met the axe when they crossed his vision of destiny. Henry’s portraits engineered invincible masculinity, while dissolutions of monasteries financed his ambitions. He demanded obedience wrapped in ritual, equating dissent with treason. The king’s body politic merged with his personal will, turning state into mirror. Despite achievements in naval power and governance, his legacy warns how dynastic obsession—and the craving for control—can sanctify cruelty.

Leopold II of Belgium (1835–1909)

Leopold II cloaked private greed in civilizing rhetoric, transforming the Congo Free State into his personal revenue machine. Rubber quotas, enforced by the Force Publique, produced an industrial-scale nightmare of mutilations, hostage-taking, and famine. While Europe applauded his philanthropy, he orchestrated public relations to sanitize atrocities and launder profits into monuments. Photographs and testimonies eventually pierced the facade, revealing a kingdom of terror built on account books. Millions perished or suffered under quotas that measured humanity by yield. Leopold’s narcissism thrived on distance—compartmentalizing horror behind humanitarian veneers. Even after international outrage forced annexation, he retained wealth and image at home. His reign exposes how self-glorification, armed with bureaucracy and rifles, can industrialize cruelty beyond battlefield lines.

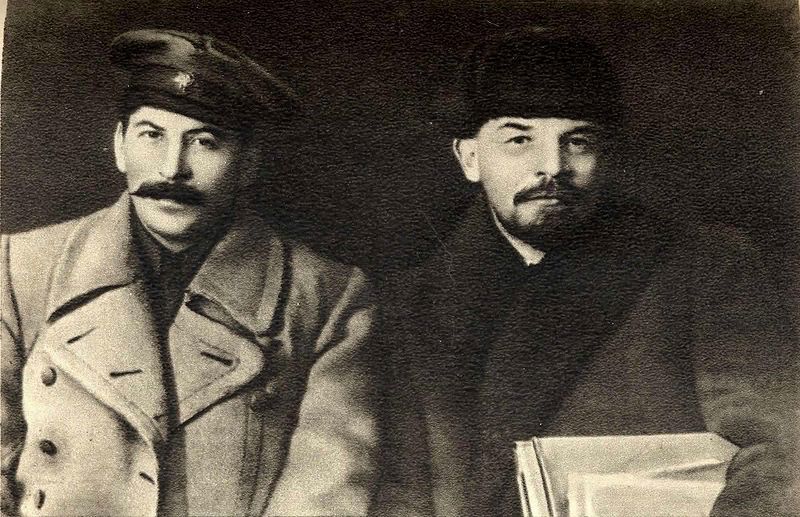

Josef Stalin (1878–1953)

Stalin weaponized paranoia into governance, elevating himself through a relentless cult of personality. Purges, show trials, and engineered famines crushed dissent and remade society into a theater of fear. Portraits and slogans cast him as father and genius, while gulags devoured perceived enemies by the millions. His self-image demanded infallibility, so facts bent to quotas and ideology. The Great Terror decapitated expertise, yet propaganda painted triumph. Even victory in war fed the myth, not accountability. Stalin’s narcissism required perpetual enemies—an endless justification for repression. Loyalty was transactional, truth malleable, and human lives expendable counters on a personal chessboard. When he died, a traumatized nation inherited shattered trust and a bureaucratic machine trained to worship the mask.

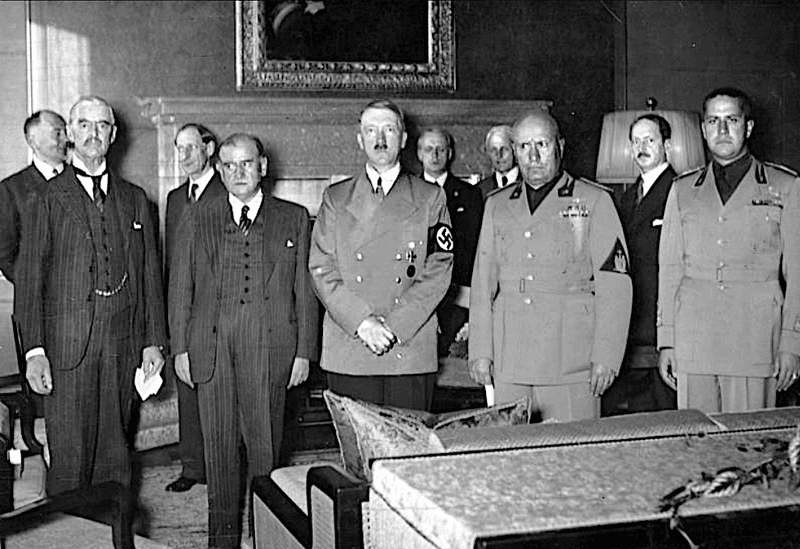

Benito Mussolini (1883–1945)

Mussolini made theater into policy, staging parades, speeches, and photographs to enshrine himself as Il Duce. Fascism’s aesthetics—uniforms, salutes, slogans—served a single portrait: his. Control of media and education cultivated a nation rehearsing adoration, while opponents vanished into prisons or silence. Militaristic swagger and imperial dreams led Italy into ruinous wars and colonial brutality. Mussolini’s narcissism prized spectacle over strategy, confusing applause with authority. Early efficiency myths masked corruption and incompetence, unraveling under pressure. As alliances collapsed, the performance faltered; the stage lights revealed a hollow script. His fall—from balcony deity to executed fugitive—shows how propaganda-fueled ego can mobilize a nation, then abandon it to catastrophe.

Emperor Hirohito of Japan (1901–1989)

Hirohito’s image, elevated by state Shinto, placed him beyond reproach as Japan embarked on imperial conquest. Whether directing or constrained, the system deified him, insulating decisions behind sacred aura. Propaganda cast war as duty to the Emperor, binding soldiers and civilians to sacrificial obedience. The imperial institution, not transparency, framed accountability. After defeat, he renounced divinity, recasting himself as a constitutional symbol to preserve the throne. This metamorphosis underscored how myth can both mobilize and absolve. The wartime cult, entwined with national identity, blurred responsibility in service of a single person’s sanctity. Hirohito’s legacy reveals how political theology magnifies leaders into untouchable icons—while the human costs smolder beneath ceremonial calm.

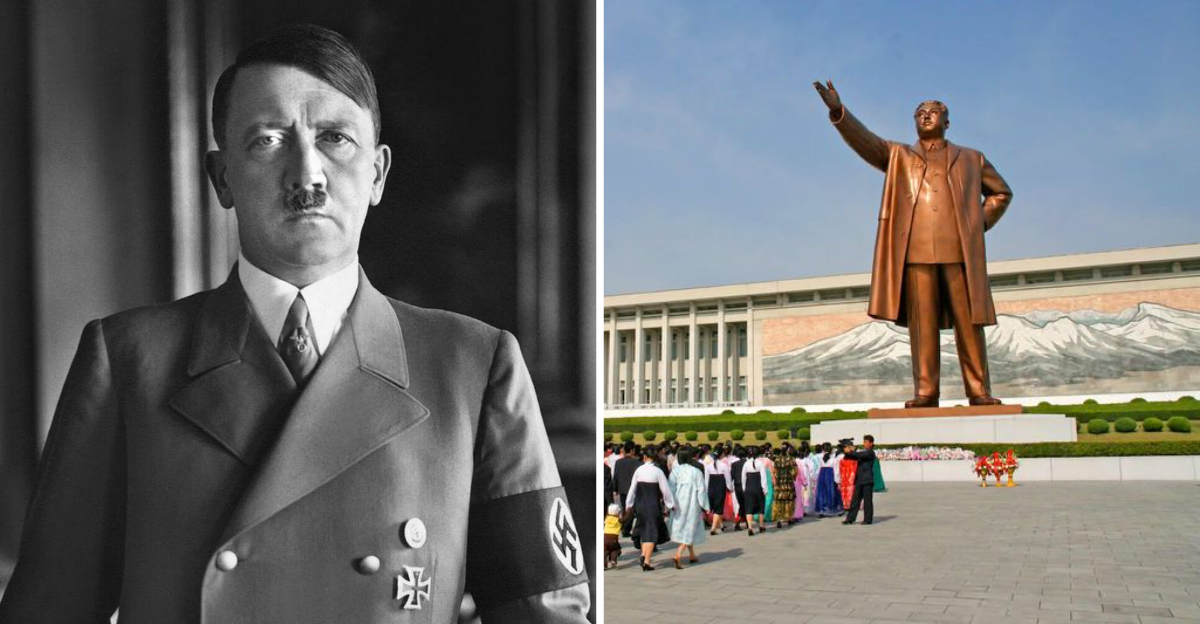

Adolf Hitler (1889–1945)

Hitler fused grievance, myth, and narcissism into a totalizing political religion. His self-styled destiny—amplified by Goebbels’s propaganda—demanded absolute loyalty and ritualized devotion. The Führer cult authorized genocidal policies, war without restraint, and the annihilation of perceived enemies. He mistook charisma for competence, substituting will for strategy and purging dissenting expertise. Early triumphs nurtured delusion, driving reckless expansion and catastrophic miscalculations. The regime’s machinery—camps, censorship, terror—was calibrated to preserve his infallibility. As defeat loomed, he blamed the nation, not himself, ordering ruin over surrender. Hitler’s end in a bunker symbolized a worldview collapsing into nihilism, leaving behind industrialized atrocity and a universal warning about the tyranny of megalomania.

Francisco Franco (1892–1975)

Franco stabilized his dictatorship with repression and ritualized reverence, presenting himself as guardian of Spain’s soul. The regime fused nationalism, Catholicism, and censorship to sanctify obedience and erase dissent. Propaganda curated an image of paternal authority, while prisons, executions, and exile enforced it. Economic modernization later softened perceptions, but fear underwrote calm. Franco’s narcissism demanded a singular Spain, purified of ideological enemies and regional identities. Statues and ceremonies embedded his presence into daily life, outlasting war’s chaos. Yet this carefully constructed myth fossilized society, constraining memory and debate. After his death, the transition revealed how much silence had been coerced. His legacy lingers in contested monuments and unresolved wounds.

Mao Zedong (1893–1976)

Mao engineered a revolutionary devotion that eclipsed institutions, enthroning his thought as living doctrine. The Great Leap Forward’s utopian quotas triggered famine and catastrophe, yet criticism equaled heresy. During the Cultural Revolution, youthful zeal smashed traditions and rival power centers to protect Mao’s supremacy. Propaganda portraits multiplied; the Little Red Book became liturgy. His charisma made policy improvisation national fate, subordinating expertise to loyalty. Mao’s narcissism demanded perpetual revolution—purity measured by proximity to his vision. Even as suffering mounted, the myth endured, recasting turmoil as virtue. China emerged transformed but scarred, its social fabric rewoven around survival. His legacy stands as a monument to ideology weaponized by personal infallibility.

Pol Pot (1925–1998)

Pol Pot pursued a year-zero fantasy that erased identity in service to an infallible ideology. Cities emptied, currency abolished, and intellect criminalized as the Khmer Rouge remade society by decree. His leadership masked insecurity with ruthless purges, extending paranoia across party lines. The killing fields recorded an experiment in purity, where dissent was imagined and mercy forbidden. Propaganda insisted on collective liberation while delivering starvation and mass graves. Pol Pot’s narcissism hid behind anonymity and slogans, yet all roads led to his will. External war and internal fractures eventually exposed the lie. Cambodia’s trauma persists—a cautionary echo of how ideological vanity, fused to absolute control, destroys a nation’s memory and future.

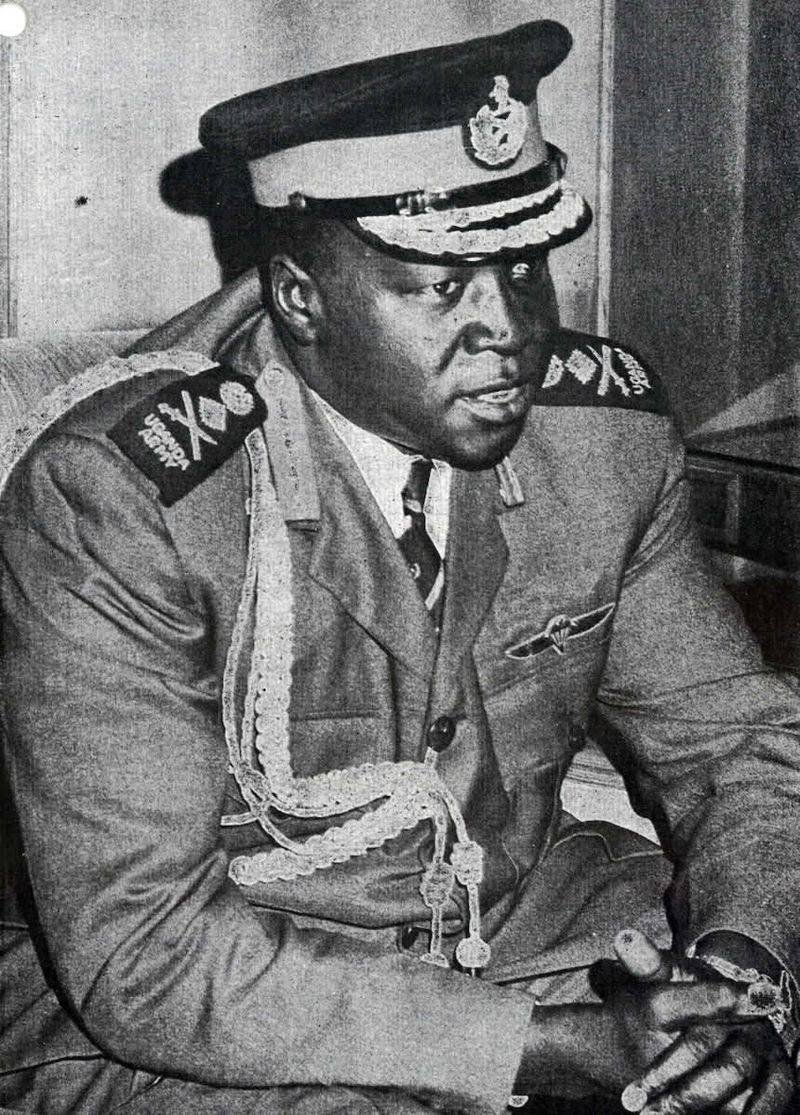

Idi Amin (c. 1925–2003)

Idi Amin transformed bravado into state policy, cloaking brutality in absurd grandiosity. He styled himself with extravagant titles, expelled Asian communities, and ruled through unpredictable terror. Behind theatrics lay a machinery of disappearances, torture, and economic collapse. Amin’s narcissism thrived on spectacle—broadcast threats, staged victories, and sycophantic ceremonies. Institutions bent to his moods; competence fled while cronies circled. International isolation grew as his delusions expanded, inviting invasion and exile. His rule shows how performative dominance—unchecked by law or norms—hollows a country. Uganda emerged traumatized and impoverished, picking through the wreckage of a dictatorship that prioritized one man’s vanity over a people’s future.

Nicolae Ceaușescu (1918–1989)

Ceaușescu curated adulation with choreographed rallies, praise poems, and omnipresent portraits, elevating himself and his wife to quasi-royal status. While austerity ravaged households, he pursued vanity megaprojects and draconian debt repayments. The Securitate policed whispers as propaganda celebrated perfection. His narcissism prized image over welfare, turning the nation into a stage of rehearsed loyalty. When reality intruded—on live television—his spell shattered into boos and revolt. The regime collapsed in days, exposing hollow institutions built on fear. Ceaușescu’s end, swift and televised, became a mirror to the lie. Romania’s recovery illustrates how quickly a cult can crumble once its audience stops performing.

Kim Il-sung (1912–1994)

Kim Il-sung established a hereditary cult that fused nationalism, siege mentality, and filial devotion into Juche. Mythology sanctified his birth, exploits, and wisdom, demanding ritualized adoration across daily life. The state reoriented history and language to orbit the “Great Leader,” institutionalizing loyalty over competence. Isolation and militarization entrenched control, while famine and purges pruned dissent. Kim’s narcissism persisted beyond death, embalmed in monuments and ideology, ensuring dynastic continuity. Propaganda substituted reality, rewarding devotion with survival. The system’s endurance shows how personality cults can crystallize into state religion. North Korea’s identity, welded to one family’s myth, remains a cautionary monument to manufactured veneration.

Muammar Gaddafi (1942–2011)

Gaddafi cast himself as revolutionary visionary, scripting Libya through the Green Book and choreographed spectacle. He blended tribal maneuvering, oil patronage, and secret police to centralize power in his persona. Eccentric theatrics—Bedouin tents abroad, Amazonian Guards—projected uniqueness while masking repression. His narcissism thrived on unpredictability: sudden diplomatic swings, erratic interventions, and internal purges. Early social gains faded under cronyism and fear. As Arab Spring protests rose, he chose annihilation over compromise, misreading legitimacy for loyalty. The regime imploded violently, scattering weapons and authority. Gaddafi’s fall illustrates how personal rule, however theatrically packaged, leaves institutions brittle—and a nation fractured once the spotlight goes dark.

Saddam Hussein (1937–2006)

Saddam engineered omnipresence—statues, murals, and televised bravado—to define Iraq’s landscape and psyche. Ba’athist ideology and secret police enforced conformity, while family networks concentrated power. His narcissism demanded invulnerability, prompting aggressive wars with Iran and the invasion of Kuwait. Defeat brought sanctions and suffering for citizens, yet the cult persisted through fear and myth. Saddam equated personal survival with national dignity, turning policy into personal vendetta. Purges and show trials kept elites compliant; ordinary people navigated whisper networks and portraits. The 2003 invasion shattered his regime and the illusions sustaining it. His capture and execution punctured the spectacle, but left behind sectarian fractures and institutional ruin.

Jean-Bédel Bokassa (1921–1996)

Bokassa crowned himself emperor in a spectacle of diamonds and debt, modeling grandeur on Napoleon while ruling through brutality. The coronation drained national coffers as schools and services withered. His narcissism demanded lavish ceremony and absolute obedience, punishing dissent with terror. International outrage mounted amid allegations of severe human rights abuses. While he posed as modernizer, corruption and vanity defined governance. A French-backed intervention ended his reign, revealing a hollow empire of costume and cruelty. Bokassa’s story shows how performative monarchy can mask predation—until the curtains part. The Central African Republic was left to rebuild from theatrics that devoured its future.

François “Papa Doc” Duvalier (1907–1971)

Papa Doc fused political repression with mystique, crafting an aura of supernatural inevitability. By entwining Vodou symbolism with the presidency, he framed dissent as sacrilege and destiny. The Tonton Macoute enforced terror as the economy withered, while propaganda painted him as healer and savior. Duvalier’s narcissism thrived on fear’s theater—midnight visits, ritual attire, and omnipresent portraits. Institutions became extensions of his persona; law bent to whispers. He cemented a dynastic path, ensuring the apparatus of intimidation outlived him. Haiti paid in lives and lost opportunity, its public sphere haunted by shadows. Papa Doc’s rule endures as a case study in charisma weaponized by superstition and surveillance.

Vlad III “the Impaler” (1431–1476/77)

Vlad built a legend on fear, turning impalement into both punishment and propaganda. In a frontier of shifting loyalties and Ottoman pressure, terror served as policy to consolidate rule. Chronicles amplified his cruelty, while local lore credited harsh order and defense. Narcissism surfaced in the deliberate crafting of myth—magnifying ruthlessness into deterrence and personal brand. Diplomacy and brutality intertwined as messages traveled by spike and rumor. Though admired by some as a defender, the spectacle eclipsed governance’s humane dimensions. His enduring notoriety shows how leaders can script themselves through horror. Vlad’s legacy is a chilling blend of patriotism and performance, where fear doubles as fame.

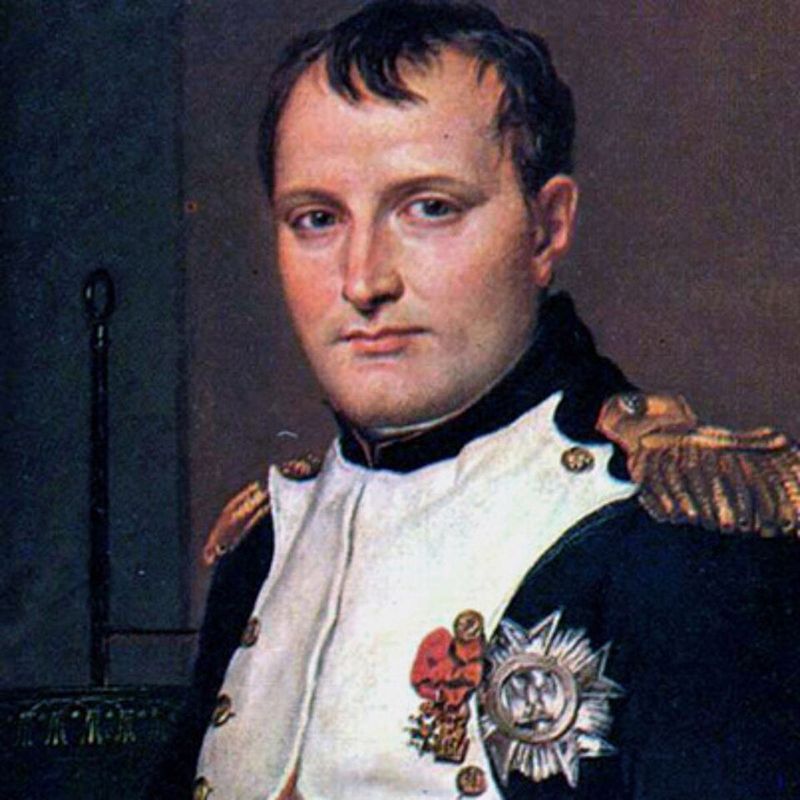

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821)

Napoleon merged tactical brilliance with insatiable ambition, enthroning himself as Emperor and recasting Europe by decree. His Code promised rational order while wars harvested glory and grief. Portraits, triumphal arches, and bulletins sculpted a hero’s image larger than defeat could contain. Narcissism fueled overreach—Spain’s quagmire, Russian winter, and denial of limits. He demanded loyalty to genius, sidelining doubt until catastrophe clarified reality. Exile became another stage, where myth refused surrender. Even in failure, his narrative dominated, proving how power can colonize memory. Napoleon’s story illustrates the double edge of vision: reform married to conquest, legacy tethered to ego’s horizon.

Tamerlane (Timur) (1336–1405)

Tamerlane forged empire through terror as strategy, searing cities and stacking skull pyramids to advertise dominion. He styled himself restorer of Mongol greatness and patron of art, erecting marvels in Samarkand while razing rivals elsewhere. This duality—splendor at home, devastation abroad—fed a legend centered on his indomitable will. Narcissism animated campaigns designed for awe as much as territory. Chronicles relay calculated cruelty meant to preempt resistance. Timurid arts flourished under a conqueror who measured worth in submission and spectacle. Succession fragility exposed empire built on a single towering persona. Timur’s legacy shines with turquoise tiles and bloodstained sand—an enduring monument to power enthralled by its own reflection.

Ivan the Terrible (1530–1584)

Ivan IV fused divine right with personal fury, inaugurating the Oprichnina to sever enemies—real or imagined—from the body politic. His temper and suspicion produced massacres, purges, and a climate of servility. Ritual and religion sanctified his wrath, while symbols of piety shielded excess. Ivan’s narcissism demanded total submission, collapsing counsel into obedience. The murder of his heir encapsulated a reign where impulse outran prudence. Cultural patronage and centralization coexisted with devastation, leaving Russia stronger yet scarred. He normalized terror as statecraft, embedding fear into governance. Ivan’s legacy warns how sacralized ego can turn sovereignty into siege—against subjects and sanity alike.

Mengistu Haile Mariam (b. 1937)

Mengistu consolidated power amid revolution, unleashing the Red Terror to extinguish rivals and frighten the populace into submission. Portraits and speeches framed him as savior of Ethiopia, while famine and war deepened under authoritarian command. His narcissism tolerated no dissent, equating criticism with counterrevolution. Mass executions, disappearances, and forced resettlements scarred communities. Ideology justified cruelty, but personal dominance set the tempo. As resistance grew and the Soviet bloc waned, his edifice cracked, leading to flight and trial in absentia. Ethiopia inherited grief and institutional distrust. Mengistu’s rule shows how revolutionary rhetoric, fused with ego and fear, can calcify into a machinery that consumes its own future.

Enver Hoxha (1908–1985)

Hoxha sealed Albania inside paranoia, severing alliances to preserve ideological purity centered on his infallibility. Cult imagery, rigid censorship, and an omnipresent security apparatus elevated him above criticism. Concrete bunkers embodied a nation militarized against phantom invasions—monuments to fear and control. His narcissism made isolation a virtue, impoverishing citizens while praising self-reliance. Purges erased rivals and history’s inconsistencies, leaving a brittle, airless public square. Even minor deviations were punished as treachery. After his death, Albania confronted the ruins of autarky and mistrust. Hoxha’s legacy is a concrete archive of ego-driven governance, where the leader’s reflection replaced the outside world.