Poetry has the power to capture human emotion, preserve history, and inspire generations across cultures and centuries. From ancient Greece to modern Poland, certain poets have created works so profound that they changed the way we see ourselves and the world around us. This collection celebrates thirty remarkable voices whose words continue to resonate, teaching us about love, loss, courage, and the beauty hidden in everyday life.

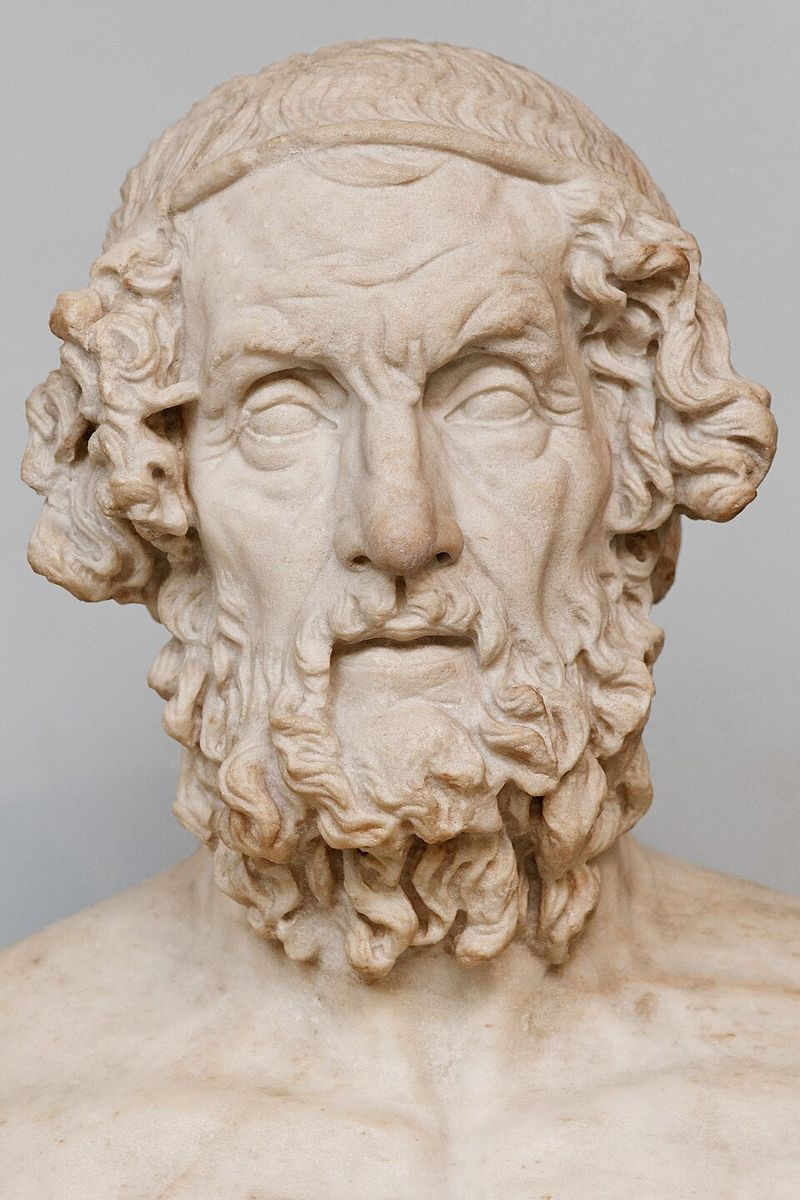

1. Homer (8th century BCE, ancient Greece)

Author of the epic pillars The Iliad and The Odyssey, Homer shaped Western storytelling with themes of heroism, fate, and homecoming that echo through literature to this day. His stories of Achilles and Odysseus introduced characters so vivid they feel real even thousands of years later.

Nobody knows if Homer was one person or many, but his influence is undeniable. Every adventure tale you read or watch owes something to his groundbreaking epics. Teachers still assign these works because they ask timeless questions about courage and identity.

2. Sappho (c. 630–570 BCE, ancient Greece)

The foremost lyric voice of antiquity, Sappho’s intimate fragments addressing love, longing, and female experience still feel startlingly modern despite their age and incompleteness. Most of her nine books of poetry were lost to history, yet what survives burns with emotional honesty.

She wrote about desire and beauty in ways that broke ancient conventions. Her verses inspired the term “sapphic” and influenced countless poets who came after. Even incomplete lines carry tremendous power, proving great art transcends time and circumstance.

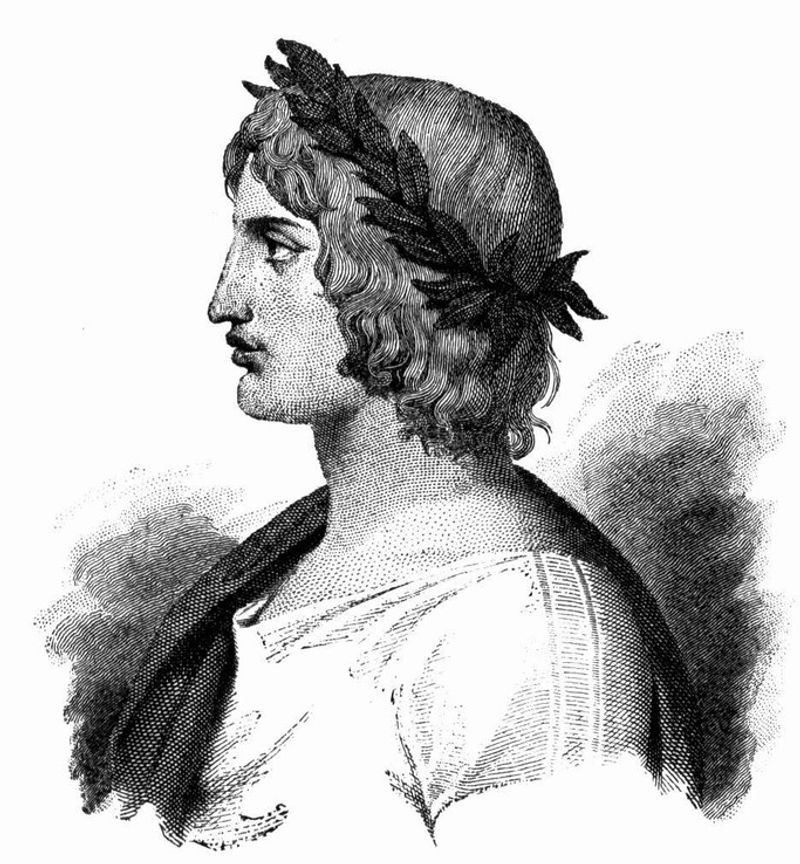

3. Virgil (70–19 BCE, Rome)

With The Aeneid (plus Eclogues and Georgics), Virgil fused epic scale with Roman identity, becoming the model Latin poet for centuries of European education. Emperor Augustus himself commissioned The Aeneid to give Rome a founding myth as grand as Homer’s tales.

Virgil spent eleven years perfecting his masterpiece but died before finishing final edits. His pastoral poems also celebrated rural life with such beauty that farmers and philosophers alike quoted them. European schools taught his Latin verses for over a thousand years.

4. Du Fu (712–770, China)

Often called “the poet-historian,” Du Fu’s precise, humane verse chronicles war, displacement, and duty; he and Li Bai form the Tang era’s defining duo. While Li Bai celebrated freedom, Du Fu documented suffering during the An Lushan Rebellion that tore China apart.

His poems show deep compassion for common people caught in political chaos. He wrote about hungry children, ruined villages, and his own family’s struggles with heartbreaking honesty. Later generations recognized his genius, even though he died poor and largely unrecognized during his lifetime.

5. Dante Alighieri (1265–1321, Italy)

The Divine Comedy reimagined the afterlife in soaring terza rima and made vernacular Italian a literary language, marrying theology, politics, and personal passion. Dante’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise remains one of literature’s most ambitious projects, blending philosophy with personal vendetta.

He wrote in everyday Italian rather than scholarly Latin, revolutionizing who could read great literature. His unrequited love for Beatrice inspired some of history’s most beautiful romantic verses. Politicians he disliked ended up burning in his fictional Hell forever.

6. Rumi (1207–1273, Persian/Turkic world)

Jalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī’s Masnavi and lyric Dīwān marry mystical love and human longing; his Sufi-inflected poetry remains globally beloved for its ecstatic wisdom. A scholar and teacher, Rumi’s life transformed when he met the wandering mystic Shams of Tabriz, whose disappearance sparked his greatest poetry.

His verses explore divine love through everyday metaphors anyone can understand. Weddings, therapy sessions, and greeting cards worldwide quote his words about connection and transformation. The whirling dervishes dance to honor his spiritual teachings and poetic legacy.

7. Hafez (c. 1315–1390, Persia/Iran)

A supreme ghazal poet, Hafez’s Dīwān blends spiritual insight, irony, and wordplay; his lines are quoted in everyday Persian life and consulted like an oracle. Iranians keep his collected poems at home the way others keep religious texts, opening random pages for guidance during difficult decisions.

His verses work on multiple levels, discussing earthly wine while hinting at spiritual intoxication. Political rulers and mystics both claimed him as their voice. His tomb in Shiraz remains one of Iran’s most visited sites, where people recite his ghazals and seek inspiration.

8. Ferdowsi (c. 940–1020, Persia/Iran)

His epic Shāhnāmeh (“Book of Kings”) preserved Persian language and myth after Arab conquest, anchoring Iranian cultural memory for a millennium. Ferdowsi spent thirty years composing sixty thousand couplets recounting Persia’s legendary and historical kings from creation to the Arab invasion.

He deliberately avoided Arabic words, keeping Persian pure and alive when it faced extinction. The work became Iran’s national epic, shaping identity through stories of heroes like Rostam. Sadly, the sultan who commissioned it paid him poorly, and Ferdowsi died disappointed despite creating an immortal masterpiece.

9. Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694, Japan)

Haiku’s great innovator; The Narrow Road to the Deep North shows his travel-poet persona, attentive to seasons, impermanence, and sudden flashes of insight. Bashō elevated the seventeen-syllable haiku from party game to profound art form, capturing entire philosophies in three brief lines.

He walked hundreds of miles through Japan’s countryside, recording observations with Zen-like simplicity. His famous frog-pond haiku demonstrates how small moments contain universal truths. Students worldwide now learn haiku because Bashō proved that brevity can hold as much meaning as lengthy epics.

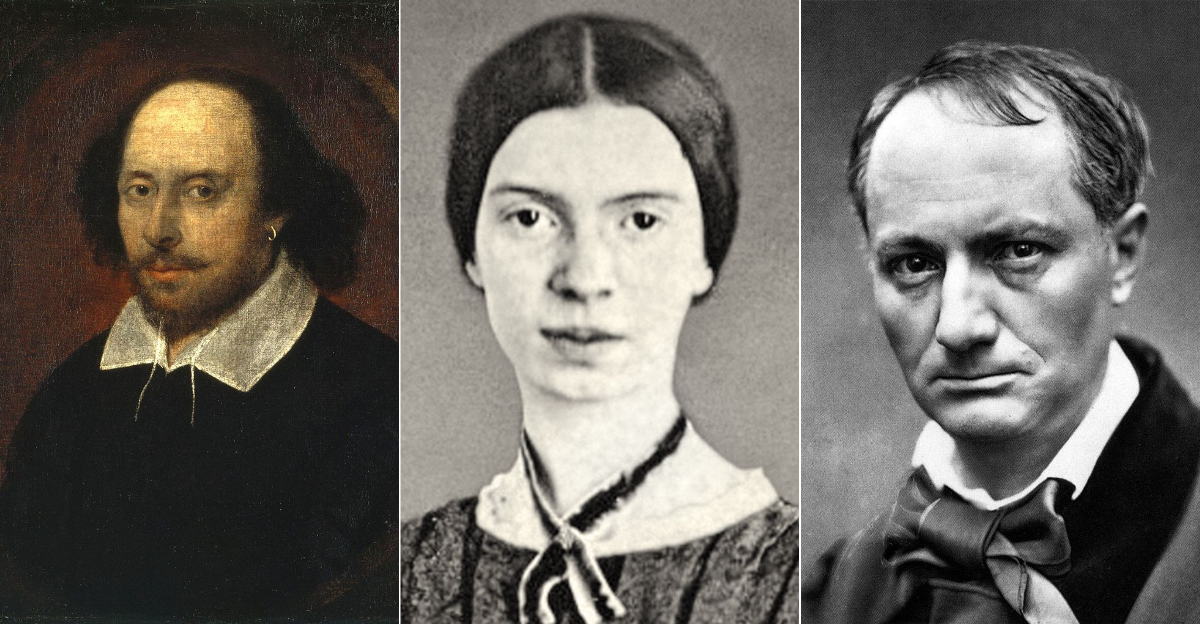

10. William Shakespeare (1564–1616, England)

Beyond the plays, the Sonnets recast desire, time, and beauty in dazzling metaphors; Shakespeare’s lyric power is a cornerstone of English poetry. His 154 sonnets explore love’s complications with such insight that phrases like “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” remain instantly recognizable four centuries later.

He invented countless words and expressions we use daily without realizing their origin. The sonnets address both a mysterious young man and a “dark lady,” sparking endless biographical speculation. His ability to capture human nature in perfect iambic pentameter remains unmatched.

11. John Milton (1608–1674, England)

Paradise Lost turned blank verse into an epic instrument; Milton’s grand style explores freedom, rebellion, and the human condition with theological audacity. He composed this masterpiece about Satan’s fall and humanity’s expulsion from Eden while completely blind, dictating thousands of lines to assistants.

His Satan became literature’s most complex villain, almost sympathetic in his defiance of tyranny. Milton supported England’s revolution and defended free speech in passionate prose. Though his politics fell from favor, his poetic ambition to “justify the ways of God to men” created English literature’s greatest religious epic.

12. William Wordsworth (1770–1850, England)

Co-author of Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth championed ordinary speech and nature’s moral force; The Prelude maps the growth of a poet’s mind. His declaration that poetry should use “language really used by men” revolutionized English verse, moving away from artificial eighteenth-century diction.

Wordsworth found spiritual lessons in simple encounters with nature and rural people. His “Daffodils” poem remains one of English literature’s most memorized works. Walking through England’s Lake District, he composed entire poems in his head before writing them down, believing physical movement aided creativity.

13. Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834, England)

Wordsworth’s partner in launching Romanticism; “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and “Kubla Khan” pair musicality with dreamlike imagination. Coleridge claimed he composed “Kubla Khan” in an opium-induced vision but forgot most of it when a visitor interrupted him, leaving us with a haunting fragment.

His mariner who shoots an albatross and suffers supernatural punishment became one of literature’s most memorable tales. Coleridge struggled with addiction and depression but produced poems of stunning musical beauty. His conversations and literary criticism influenced an entire generation of writers beyond his own verses.

14. Lord Byron (1788–1824, England)

Flamboyant and influential, Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and Don Juan made the Byronic hero a lasting archetype: rebellious, witty, world-weary. He became the first literary celebrity, with fans copying his hairstyle and scandals filling newspapers across Europe.

Byron’s personal life was as dramatic as his poetry, featuring affairs, debts, and exile from England. He died fighting for Greek independence, cementing his reputation as a romantic hero. His satirical masterpiece Don Juan mocked society with such charm that even his targets laughed. The moody, attractive outsider in countless novels descends directly from Byron’s self-fashioned image.

15. Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822, England)

A radical idealist with lyrical fire; “Ode to the West Wind” and “Ozymandias” fuse music, political hope, and meditations on time and power. Shelley believed poets were “the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” capable of inspiring social change through beauty and truth.

Expelled from Oxford for atheism, he lived in scandalous exile with Mary Shelley (who wrote Frankenstein). His “Ozymandias” shows even mighty rulers crumble to dust, while “West Wind” calls for revolutionary transformation. Tragically, he drowned at twenty-nine when his sailboat sank, robbing literature of decades more visionary work.

16. John Keats (1795–1821, England)

In a tragically brief life, Keats crafted the English language’s most sensuous odes: “To Autumn,” “Nightingale,” “Grecian Urn,” probing beauty, art, and mortality. Tuberculosis killed him at just twenty-five, yet his final years produced some of English poetry’s most perfect works.

Keats trained as a surgeon before devoting himself to poetry, bringing medical precision to his observations of nature. His odes explore how beauty and truth intersect, creating lines that feel physically delicious to speak aloud. He requested his tombstone read “Here lies one whose name was writ in water,” yet his reputation only grew after death.

17. Walt Whitman (1819–1892, USA)

Leaves of Grass broke forms open with free verse and democratic embrace; Whitman’s expansive “I” redefined the American poetic voice. He self-published the first edition in 1855 and kept revising it throughout his life, eventually expanding six poems to nearly four hundred.

Whitman celebrated the body, democracy, and common people with unprecedented frankness. His Civil War nursing experiences deepened his poetry’s compassion. Critics called his work crude and immoral, but he persisted in believing American poetry needed a new, bold voice. Modern free verse poetry descends directly from his revolutionary experiments.

18. Emily Dickinson (1830–1886, USA)

Compressed, slant-rhyme miniatures that explode with metaphysical voltage; writing largely in private, Dickinson reinvented lyric intensity from Amherst. She rarely left her family’s Massachusetts home and published fewer than a dozen poems during her lifetime, yet left behind nearly eighteen hundred works.

Her dashes, unusual capitalization, and compact forms felt strange to Victorian readers but seem modern today. Dickinson wrote about death, immortality, nature, and consciousness with startling originality. Her sister discovered the poems after her death and spent years getting them published. Now she ranks among America’s greatest poets despite her reclusive life.

19. Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867, France)

Les Fleurs du mal mapped modern urban alienation and decadent beauty; his symbolism shaped Rimbaud, Mallarmé, and the entire modernist turn. Baudelaire found poetry in Paris’s dark corners, celebrating prostitutes, wine, and decay alongside traditional beauty, shocking conservative readers.

He was prosecuted for obscenity when Les Fleurs du mal appeared in 1857, forced to remove six poems. His theory of correspondences, where senses blend and symbols resonate across reality, influenced generations of poets. Despite chronic debt and illness, he translated Edgar Allan Poe and pioneered the prose poem, forever changing what poetry could be.

20. Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837, Russia)

Founding figure of modern Russian literature; Eugene Onegin (novel-in-verse) and lyrics blended wit, romance, and social critique in supple Russian. Pushkin transformed Russian from a language of bureaucracy into a flexible literary instrument, much as Shakespeare shaped English.

His African heritage (through his great-grandfather) made him unique among Russian aristocrats, a fact he acknowledged with pride. Eugene Onegin’s bored hero and rejected Tatyana became archetypes of Russian literature. Tragically, Pushkin died at thirty-seven from wounds in a duel defending his wife’s honor, cutting short Russia’s greatest poetic genius.

21. W. B. Yeats (1865–1939, Ireland)

From Celtic twilight to stark modernism, Yeats evolved relentlessly; poems like “Easter 1916” and The Tower examine art, nation, and aging with spellbinding craft. He began writing dreamy verses about Irish fairy legends but transformed himself into a hard-edged modernist confronting political violence and personal mortality.

Yeats helped establish Dublin’s Abbey Theatre and served as an Irish senator. His unrequited love for Maud Gonne inspired decades of poetry. “Easter 1916” captures his complex feelings about the Irish rebellion, recognizing how “a terrible beauty is born” from violence. He won the Nobel Prize in 1923.

22. T. S. Eliot (1888–1965, USA/UK)

“The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” The Waste Land, Four Quartets: Eliot captured spiritual drift and searched for order in fractured modernity. His 1922 masterpiece The Waste Land expressed post-World War I disillusionment through fragmented voices, multiple languages, and obscure references, changing poetry forever.

Born in St. Louis, Eliot moved to England and became more English than the English, converting to Anglo-Catholicism. His early work portrayed modern anxiety and paralysis; later poems explored religious faith. Though his verse could seem difficult, his Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats inspired the musical Cats, proving his range.

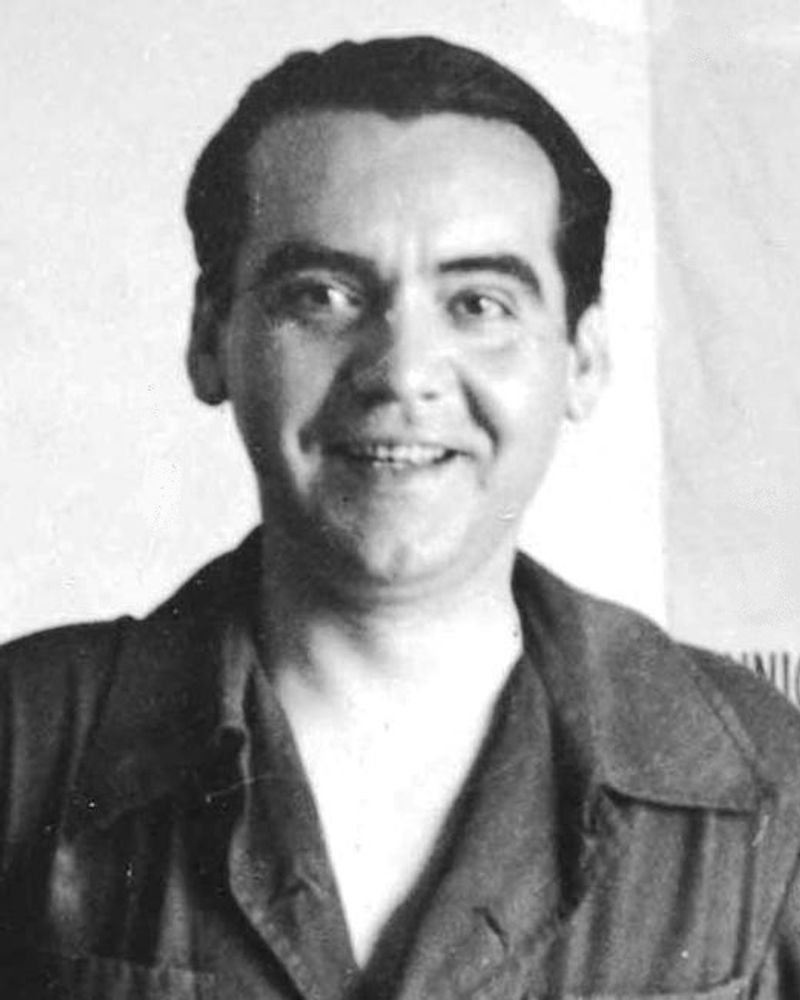

23. Federico García Lorca (1898–1936, Spain)

Romantic, surreal, and folk-rooted; Romancero gitano and Poet in New York marry duende (soulful intensity) with political courage, silenced by assassination. Lorca blended Andalusian gypsy ballads with avant-garde surrealism, creating a uniquely Spanish modernism that honored tradition while embracing experimentation.

A talented pianist and playwright as well as poet, he directed a traveling theater troupe bringing classics to rural villages. His openness about homosexuality and leftist sympathies made him a target when Spanish Civil War began. Fascist forces executed him in 1936 at age thirty-eight, making him a martyr for artistic freedom.

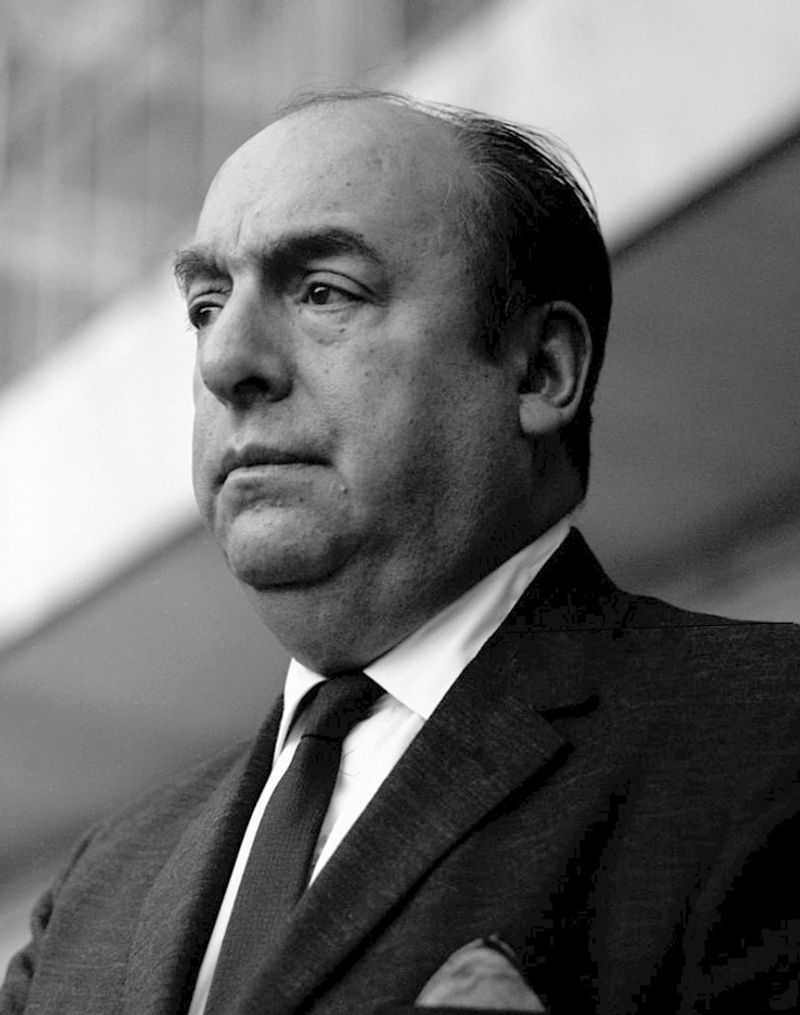

24. Pablo Neruda (1904–1973, Chile)

From Twenty Love Poems to Canto General, Neruda spanned intimacy and continent-sized history; his lush metaphors helped earn a Nobel Prize (1971). His early love poems made him famous as a teenager, but he grew into an epic poet chronicling Latin America’s struggles and celebrating its landscapes.

Neruda served as diplomat and senator, facing exile for his communist politics. He wrote odes to simple things like tomatoes, socks, and onions, finding poetry everywhere. His three memoir-houses in Chile attract visitors worldwide. He died just days after Pinochet’s coup, under circumstances still debated today.

25. Langston Hughes (1901–1967, USA)

The Harlem Renaissance’s heartbeat; The Weary Blues and later jazz-inflected sequences honor Black speech rhythms, resilience, and everyday dignity. Hughes captured African American life with such authenticity that his poems feel like overheard conversations, songs, and dreams from Harlem’s streets.

He incorporated blues and jazz rhythms into poetry, creating a distinctly Black American sound. His simple language carried profound statements about racial injustice and hope. “A Dream Deferred” became an anthem of the civil rights movement. Hughes traveled widely, wrote plays and essays, and mentored younger writers throughout his prolific career.

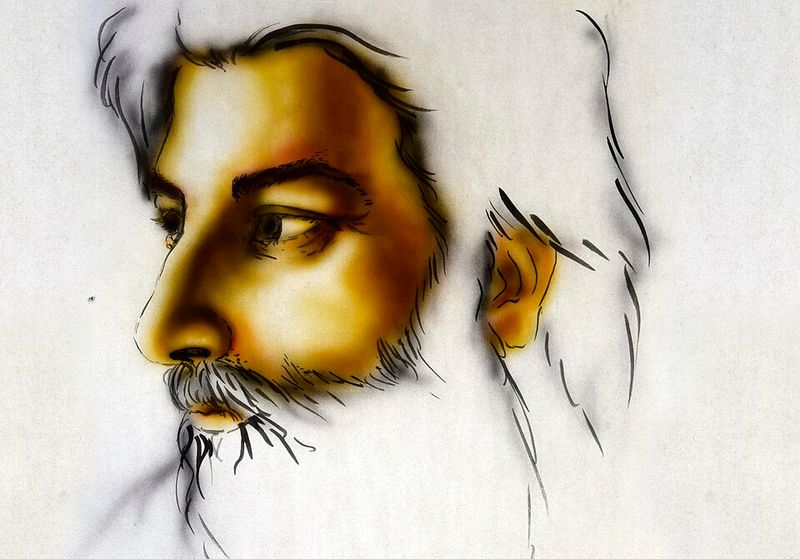

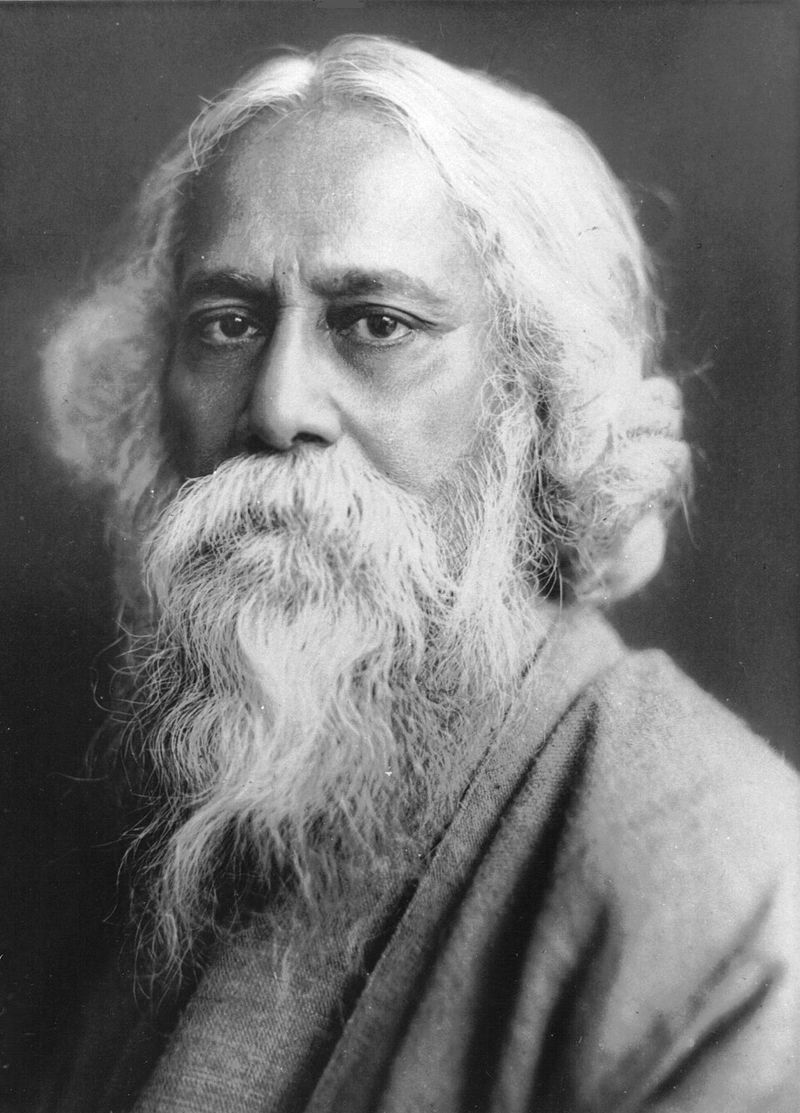

26. Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941, India)

First non-European Nobel in Literature (1913) for Gitanjali; Tagore’s devotional simplicity and humanism ripple through South Asian arts and education. He translated his own Bengali poems into English, winning over Western readers with their spiritual grace and universal themes of love and nature.

Tagore composed thousands of songs (including India’s and Bangladesh’s national anthems), founded a progressive school, and painted prolifically. His work bridges Eastern and Western traditions, promoting understanding across cultures. Gandhi called him “Great Sentinel,” and his birthday is celebrated across Bengal. His influence on South Asian culture cannot be overstated.

27. Anna Akhmatova (1889–1966, Russia)

A piercing witness to terror and endurance; the cycle Requiem and later work honor private grief and public tragedy with classical poise. Akhmatova survived Stalin’s purges that killed her first husband, imprisoned her son repeatedly, and silenced her for decades, yet she refused to emigrate.

Her early love lyrics made her famous before the Revolution. Requiem, written in fragments memorized by friends because writing was dangerous, mourns all mothers whose children were arrested. She stood in prison lines for seventeen months trying to help her son. Her dignified survival and refusal to compromise made her a moral beacon for Russian intellectuals.

28. Wisława Szymborska (1923–2012, Poland)

The Nobel laureate of sly clarity; in books like View with a Grain of Sand, she finds universe-sized wonder in everyday objects, jokes, and questions. Szymborska wrote with deceptive simplicity, using humor and curiosity to explore profound philosophical questions about existence, history, and human nature.

She published relatively few poems, revising endlessly and rejecting her early communist-era work. Her verses often begin with ordinary observations that spiral into cosmic implications. Winning the Nobel in 1996 brought unwanted fame to this private person. She preferred quiet life in Krakow, writing book reviews and poetry that proves wisdom need not sound solemn.