Heat waves aren’t just “bad summer weather” anymore. They’re becoming a global risk that could reshape everyday life.

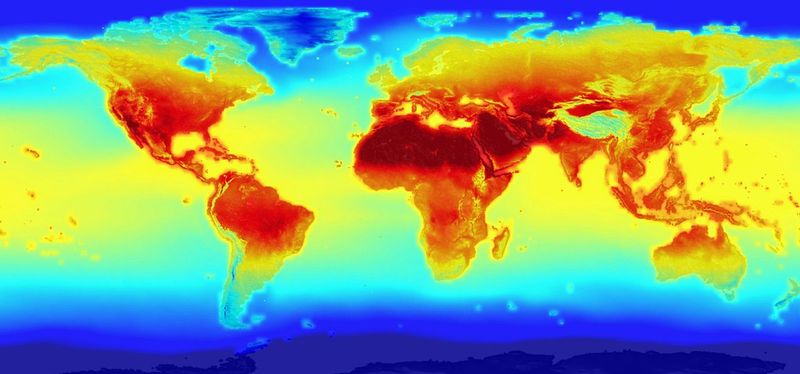

If temperatures keep rising, Oxford researchers warn that by 2050 nearly half the world’s population could be living in dangerously hot conditions. That doesn’t only mean sweaty commutes and sleepless nights; it can affect how people work, how cities function, and how safe it is to be outdoors.

Here’s what the science says is changing and why the heat problem is getting harder to ignore.

1. This isn’t just ‘hot summers’. It’s heat that can become dangerous to live with.

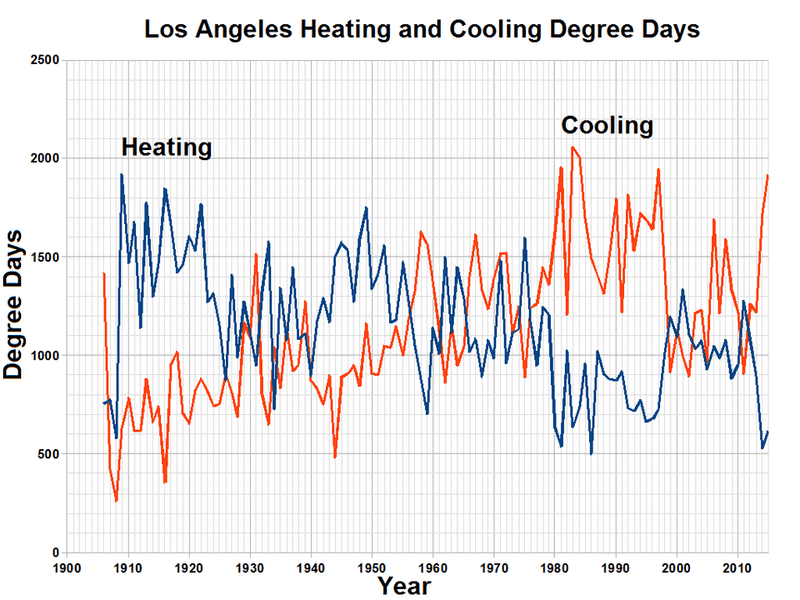

Scientists aren’t talking about sweaty afternoons that make you crank up the fan. They’re measuring something called cooling degree days, which sounds technical but basically tracks how much extra cooling we need when temperatures soar.

When I first heard about CDDs, I thought it was just another boring metric, but it actually tells us when heat stops being annoying and starts being dangerous.

Heat becomes a real problem when it’s not occasional anymore. Instead of a few hot days here and there, we’re looking at prolonged periods that affect everything from your health to your electric bill.

Your body can handle a heat wave for a day or two, but weeks of relentless high temperatures? That’s a different story entirely.

The infrastructure we rely on wasn’t built for this kind of sustained heat. Roads buckle, power grids strain, and suddenly your home needs cooling systems running constantly just to stay livable.

This shift from “uncomfortable” to “genuinely hazardous” is what keeps climate scientists up at night, and honestly, it should concern all of us too.

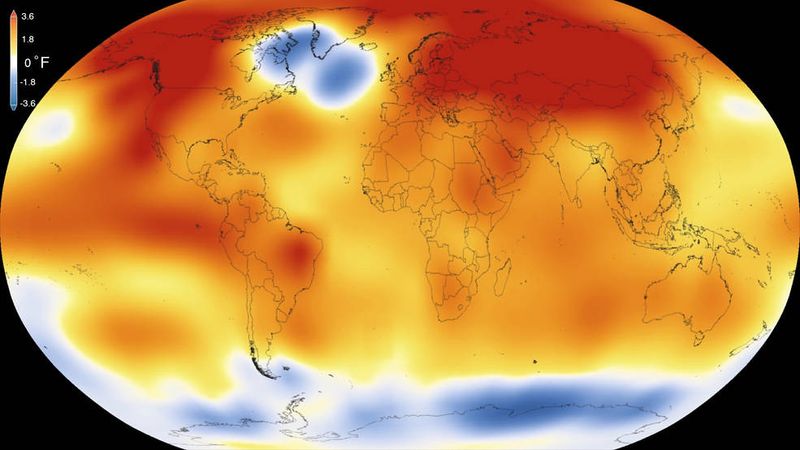

2. The headline number depends on crossing (or effectively living in) a 2°C world.

That jaw-dropping figure of 4 billion people? It’s tied directly to a specific scenario where Earth warms by 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Scientists at Oxford didn’t just pick this number randomly – they’re looking at what happens when we cross that particular threshold, which many experts now think is increasingly likely without major changes.

Two degrees might sound tiny when you’re checking the weather forecast. But on a global scale, it’s massive.

We’re talking about a fundamental shift in climate patterns that reshapes where and how people can live comfortably.

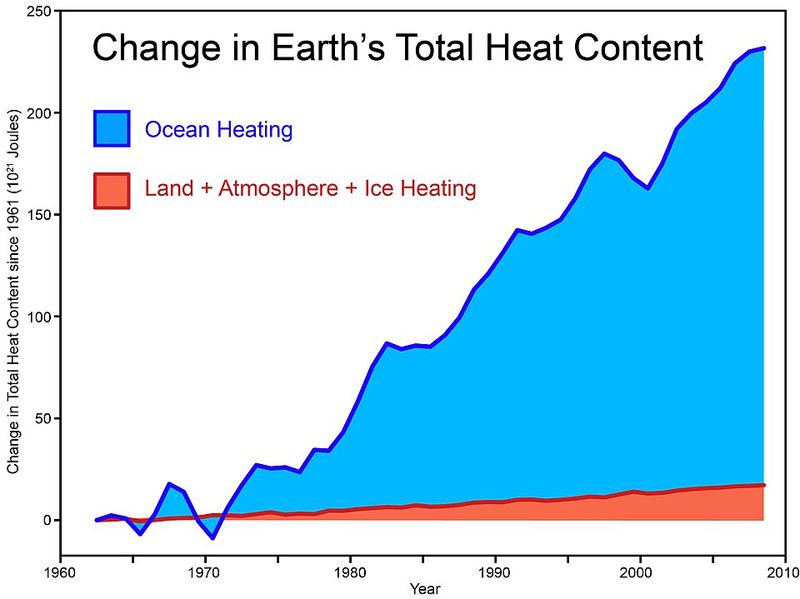

The scary part is that we’re already past 1 degree of warming, so 2 degrees isn’t some far-off possibility anymore. Without stronger climate action, we’re barreling toward this scenario faster than most people realize.

Every fraction of a degree matters because each increment brings hundreds of millions more people into dangerous heat zones.

This isn’t fearmongering – it’s what the models consistently show when scientists plug in current emission trends and policy commitments.

3. The jump is huge: from 23% of people in 2010 to 41% by 2050 (in this scenario).

Back in 2010, roughly 23% of humanity lived in areas experiencing extreme heat conditions. Fast forward to 2050 in this 2-degree scenario, and that number nearly doubles to 41%.

That’s not a gradual increase – it’s a dramatic leap that happens within a single generation.

Think about what that means in real numbers. We’re talking about billions of additional people suddenly dealing with heat that their grandparents never experienced.

Communities that were once temperate will be scrambling to adapt to conditions they’re completely unprepared for.

I tried explaining this to my neighbor once, and his first reaction was disbelief. How could the percentage almost double in just 40 years?

But the math is straightforward when you understand how warming affects different regions at different rates.

The people moving into this category aren’t just those in traditionally hot climates. They include populations in areas that never needed significant cooling before.

That’s what makes this projection so disruptive – it’s not just more of the same, it’s a fundamental reshaping of where extreme heat becomes the norm.

4. The impacts ramp up fast – before the world even clears 1.5°C.

Here’s something that caught scientists off guard: most of the dramatic increases in heating and cooling demand happen before we even hit 1.5 degrees of warming. That’s the threshold many countries committed to avoiding in the Paris Agreement, yet the worst changes arrive earlier than that target suggests.

This timing problem is crucial because it means adaptation can’t wait. If your climate action plan assumes you’ll start preparing once we reach 1.5 degrees, you’re already behind.

The steep climb in extreme heat days is happening right now, in the space between 1 and 1.5 degrees.

Cities and countries banking on gradual change are in for a rude awakening. The transition isn’t smooth or linear – it accelerates in ways that catch unprepared communities completely flat-footed.

Building codes, infrastructure investments, and public health systems all need upgrading sooner than policymakers initially thought.

What really drives this point home is that we’re likely to cross 1.5 degrees within the next decade or so. That means the adaptation challenges are already knocking on our door, not waiting politely for some future date.

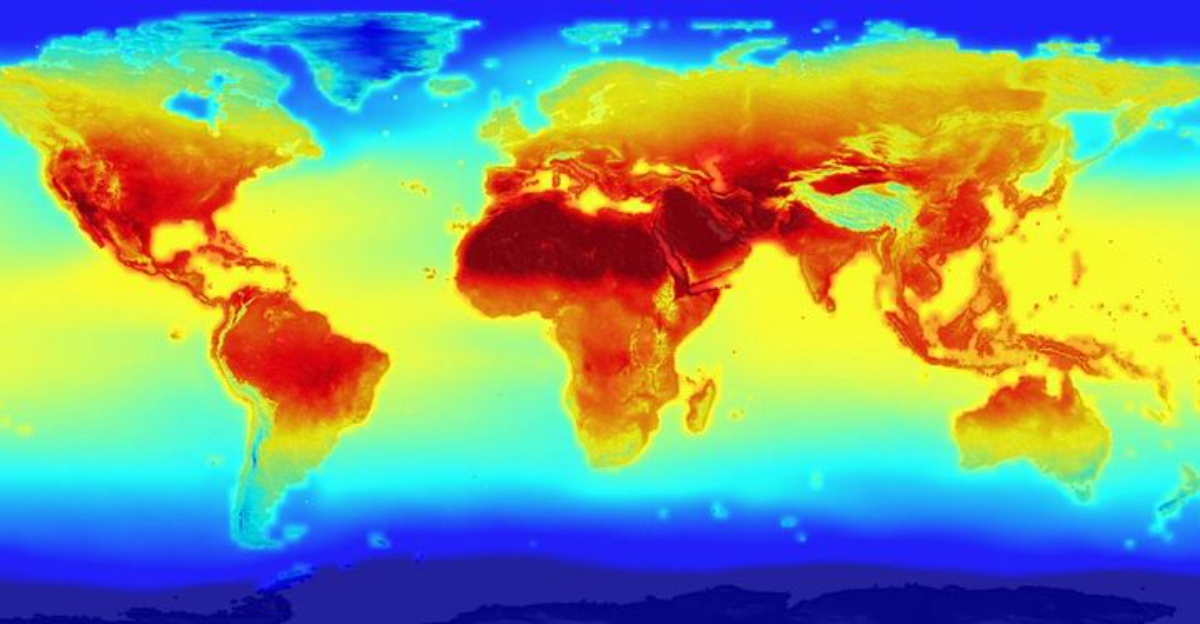

5. Where heat rises fastest isn’t always where the most people are.

Geography plays tricks when it comes to extreme heat. Countries seeing the sharpest temperature spikes include Central African Republic, Nigeria, South Sudan, Laos, and Brazil.

These places will experience some of the most intense heating increases on the planet, even though they don’t necessarily have the world’s largest populations.

The pattern reveals something important about climate change: it doesn’t distribute impacts evenly or fairly. Some regions get hammered with temperature increases that far exceed the global average.

Others see more moderate changes but affect vastly more people because of population density.

What makes this particularly challenging is that many of these rapidly heating countries have the fewest resources to adapt. They’re dealing with the steepest climbs in dangerous heat days while often lacking the infrastructure, healthcare systems, and economic capacity to respond effectively.

It’s a cruel irony that keeps climate justice advocates up at night.

Understanding this geographic mismatch matters because international climate aid and adaptation funding needs to account for both rapid change and population size. The countries heating fastest need support just as urgently as those with the most people exposed.

6. But the largest numbers of affected people are expected in a different set of countries.

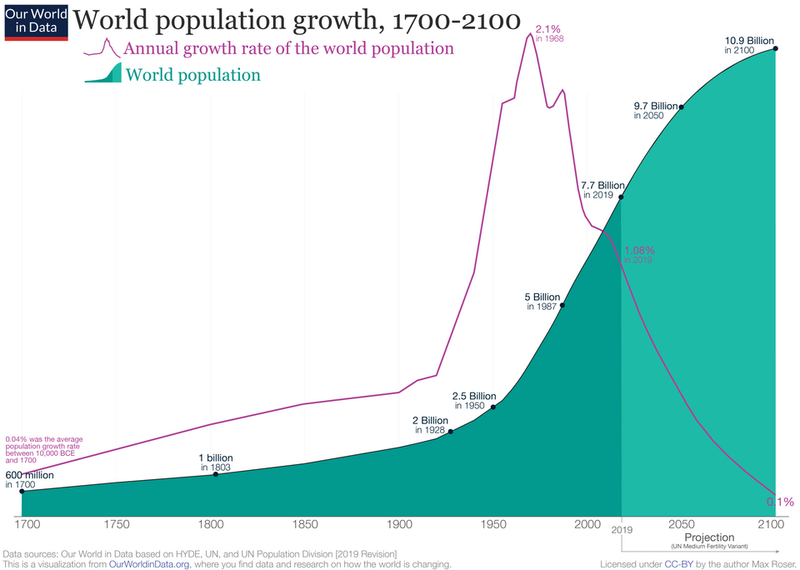

Flip the equation around and look at sheer population numbers, and you get a completely different list. India, Nigeria, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and the Philippines top the charts for total people exposed to extreme heat.

These nations combine large populations with significant warming, creating a perfect storm of climate vulnerability.

India alone could see hundreds of millions of additional people living in dangerously hot conditions. When you’re talking about populations in the billions, even moderate temperature increases affect staggering numbers of individuals.

Every percentage point of warming translates to tens of millions more people struggling with heat.

These countries also tend to have younger populations and rapidly growing cities. That means the people moving into extreme heat zones include millions of children whose entire lives will be shaped by these hotter conditions.

Their schools, homes, and future job prospects all get influenced by this thermal shift.

The infrastructure challenge in these densely populated nations is mind-boggling. You can’t just install air conditioning for hundreds of millions of people overnight, especially when many lack reliable electricity access to begin with.

7. ‘Cold’ countries are not safe – because their buildings are built to trap heat.

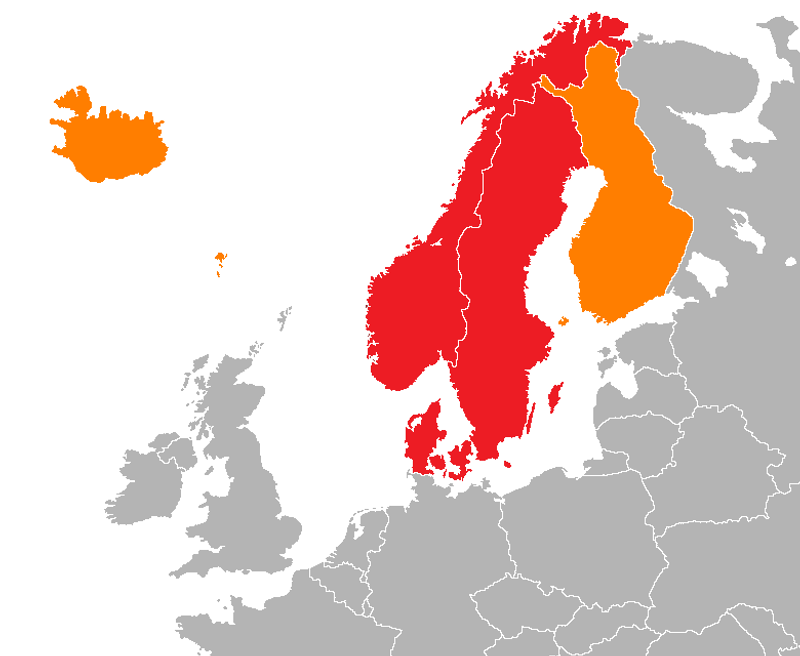

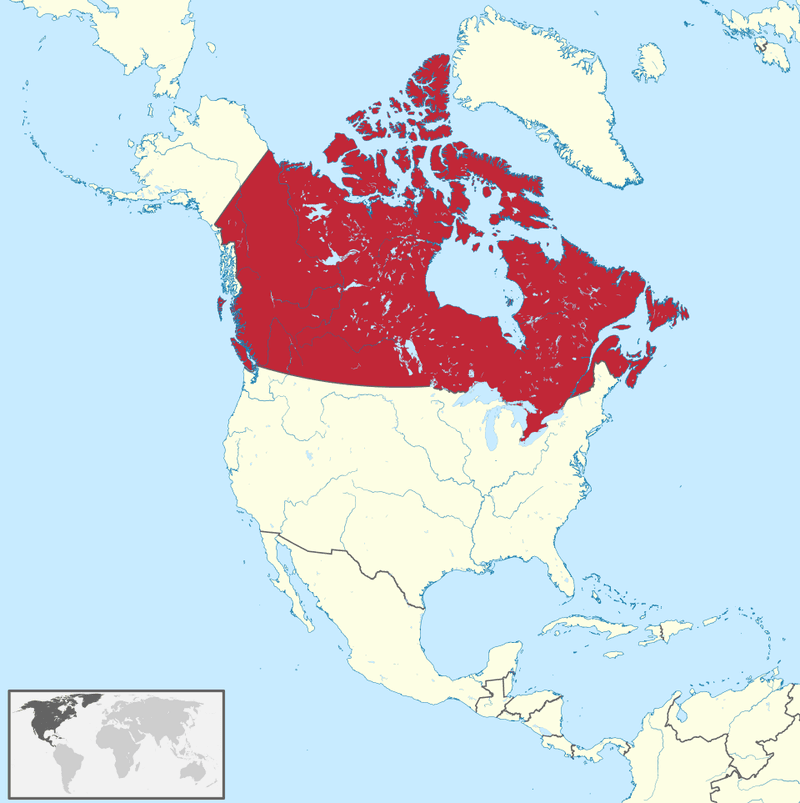

Countries known for cold winters face a weird problem: their buildings are designed to do exactly the opposite of what they’ll need in a warmer world. Homes in places like Scandinavia, Canada, and northern Europe are built to trap heat and keep it inside.

Great for January, terrible for increasingly common summer heat waves.

I visited Stockholm during an unusual heat wave a few years back, and locals were genuinely suffering. Their apartments became ovens because there’s minimal air conditioning and windows aren’t designed for cross-ventilation.

The very features that make these buildings energy-efficient in winter become liabilities when temperatures soar.

This architectural mismatch means cold-climate countries could see proportionally larger impacts from warming. A few extra hot days might not sound like much, but when your entire built environment is optimized for cold, those days become genuinely dangerous.

Elderly residents and people with health conditions face serious risks in buildings that can’t shed heat.

Retrofitting millions of cold-climate buildings for heat isn’t cheap or quick. It’s a massive infrastructure challenge that these countries never anticipated when constructing their housing stock.

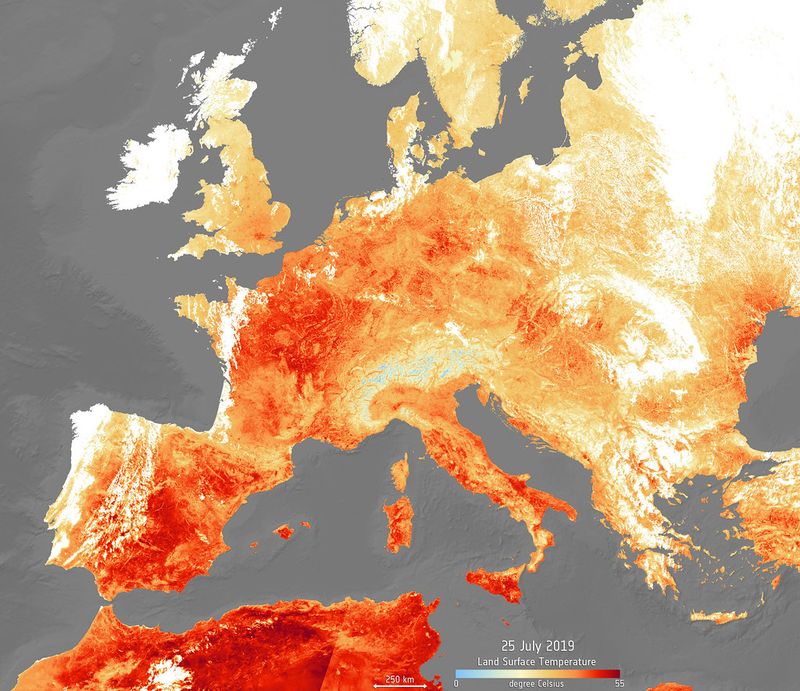

8. The relative jumps in parts of Europe are startling.

Crunch the numbers on Europe and your jaw drops. Moving from 1 degree to 2 degrees of warming could mean hot days more than double in Austria and Canada.

The UK, Sweden, and Finland might see increases around 150%. Norway could experience a 200% jump, and Ireland?

A whopping 230% increase in dangerously hot days.

These aren’t small adjustments – they’re fundamental transformations of what “normal weather” means. A country that averaged 10 extremely hot days per year suddenly facing 33 is dealing with a completely different climate reality.

Schools, workplaces, and healthcare systems all need rethinking.

What’s particularly striking is that these percentages represent relative changes from a low baseline. Even after these increases, places like Ireland won’t be as hot as equatorial regions.

But the shock to systems and people adapted to cool climates is enormous.

Europeans have already experienced deadly heat waves in recent years, and those happened at current warming levels. Doubling or tripling the frequency of such events would fundamentally alter European life, from agriculture to tourism to urban planning.

9. The ‘air conditioning dilemma’ is real: more cooling can also mean more emissions.

We’ve created a vicious cycle that would be funny if it weren’t so serious. Extreme heat drives people to install air conditioning, which requires massive amounts of electricity.

If that electricity comes from fossil fuels, you’re pumping out more emissions, which causes more warming, which creates more demand for cooling. Round and round we go.

The Oxford study explicitly connects rising heat exposure to rising cooling needs, and that connection has huge implications. Without clean energy powering those air conditioners, we’re essentially using climate change to fight climate change – and losing.

It’s like trying to bail out a boat while simultaneously drilling holes in the bottom.

Countries racing to install cooling systems face a genuine dilemma. People need relief from dangerous heat right now, but locking in fossil-fuel-powered cooling for decades makes the underlying problem worse.

The solution requires both rapid deployment of cooling technology and equally rapid decarbonization of electricity grids.

Efficient building design can reduce cooling needs significantly, but that requires upfront investment and planning. Many rapidly developing regions are installing cheap, inefficient systems that will haunt them for generations.

10. This becomes a health, jobs, and inequality story – not only a climate story.

Extreme heat doesn’t just make thermometers rise – it ripples through every aspect of society in ways that amplify existing inequalities. Outdoor workers face impossible choices between earning a living and risking heat stroke.

Construction crews, agricultural laborers, and delivery drivers can’t just work from home when temperatures soar.

Schools become learning deserts when kids are too hot to concentrate. Studies show cognitive performance drops significantly in overheated classrooms, which means children in poorly cooled schools fall behind their peers in climate-controlled environments.

Educational inequality gets baked into the temperature difference.

Migration pressure builds as entire regions become less habitable. People don’t abandon their homes casually, but when heat makes farming impossible or outdoor work too dangerous, they have limited options.

This creates refugee flows that strain receiving communities and spark political conflicts.

Food systems take direct hits too. Crops fail, livestock suffer, and supply chains dependent on outdoor labor break down during extreme heat events.

Oxford researchers emphasize these broader impacts because they show how overshooting 1.5 degrees isn’t just an environmental issue – it’s a civilization-reshaping force.

11. The ‘fix’ isn’t one thing – it’s buildings + cities + energy + public health.

Anyone promising a single silver bullet for extreme heat is selling snake oil. The actual solution is a complex web of interventions across multiple systems working together.

Buildings need redesigning with better insulation, reflective surfaces, and passive cooling. Cities require more green spaces, cooler pavements, and strategic shade.

Energy systems must shift to renewables fast enough to power all that cooling without worsening emissions. That means massive grid upgrades, storage solutions, and efficiency improvements happening simultaneously.

It’s an infrastructure transformation on a scale most countries have never attempted.

Public health systems need expansion too. Heat early-warning systems, cooling centers, and medical capacity for heat-related illness all require investment.

Emergency services must prepare for heat waves the way they prepare for hurricanes or floods.

The Oxford study points toward practical adaptation needs, especially in the built environment, alongside rapid decarbonization. The key word is “alongside” – you can’t pick one or the other.

Adaptation without emissions cuts means adapting to ever-worse conditions. Emissions cuts without adaptation leave people vulnerable to changes already locked in.

12. The message is basically: adaptation must start earlier than policymakers think.

Procrastination is a luxury we no longer have. If your climate adaptation plan assumes you’ll start making changes “later,” Oxford’s research has bad news: later is too late.

The steep increases in cooling and heating demand show up before we cross the temperature thresholds that many plans use as triggers for action.

Policymakers love to schedule things for future administrations – it’s politically convenient and spreads costs over time. But climate change doesn’t care about election cycles or budget planning horizons.

The changes are arriving faster than the typical pace of government action, creating a dangerous gap.

Cities that wait until heat becomes unbearable before investing in adaptation will face crisis management instead of orderly preparation. The difference is enormous in both human suffering and financial cost.

Emergency responses always cost more than planned preparation.

What makes this particularly frustrating is that we have the knowledge and technology to adapt. The barrier isn’t technical – it’s political will and resource allocation.

We know what needs doing; we’re just not doing it fast enough because the urgency hasn’t fully sunk in yet.