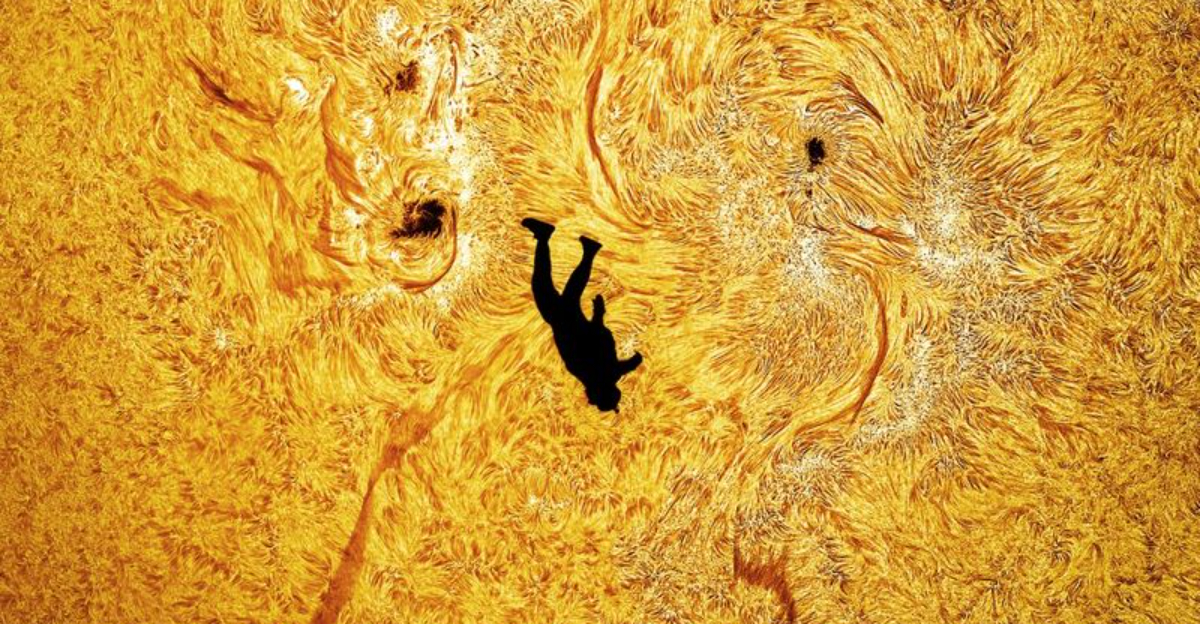

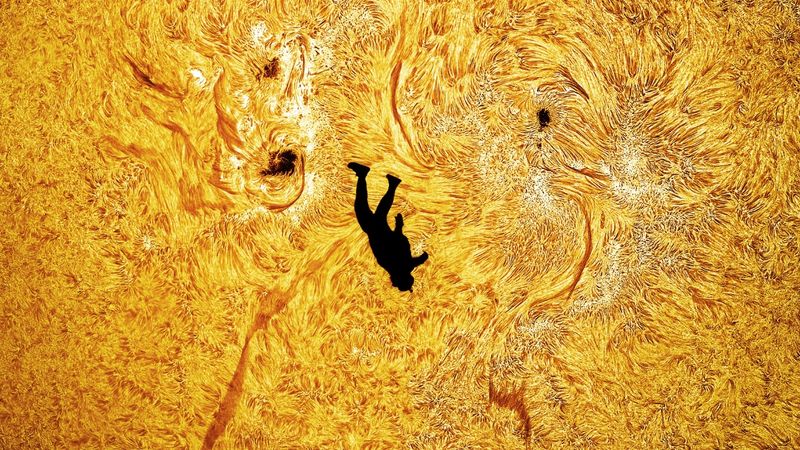

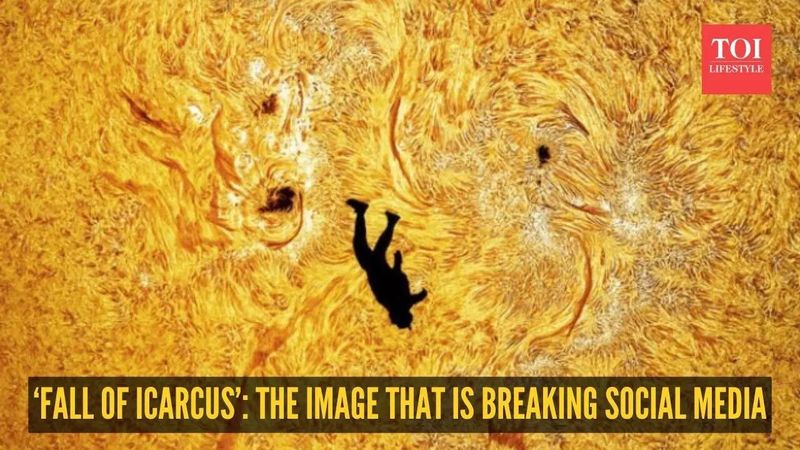

What does it take to frame a human silhouette against the living surface of the Sun? On November 8, 2025, astrophotographer Andrew McCarthy and skydiver Gabriel C. Brown orchestrated a once-in-a-lifetime alignment that looks like a plunge into a star. The image, titled “The Fall of Icarus,” fuses extreme sport with precision solar imaging to stunning effect. Here are three things that reveal why this audacious shot matters—and how it was even possible.

The impossible alignment

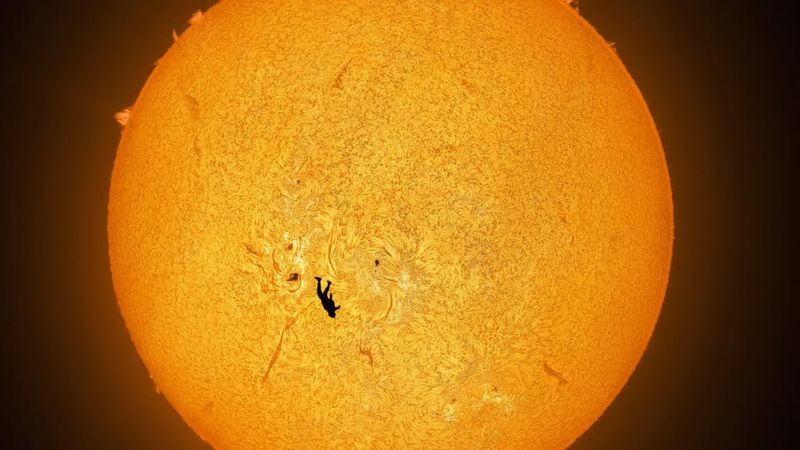

“The Fall of Icarus” hinges on a razor-thin alignment between a fast-descending human and a 1.4-million-kilometer-wide star. On November 8, 2025, Andrew McCarthy positioned his solar rig roughly 8,000 feet away from Gabriel C. Brown’s 3,500-foot jump path, synchronizing plane, jumper, camera, and Sun. It reportedly took six aerial attempts to thread the silhouette across the hydrogen-alpha Sun, revealing the chromosphere while preserving the crisp human outline. This isn’t a digital composite trick; it’s choreography of physics, geography, and time. The Sun sits 93 million miles away, yet the human figure resolves sharply against swirling prominences. That juxtaposition sells the illusion of a plunge while honoring reality: an atmospheric alignment, not a stellar descent. The result is both preposterous and precise—an engineered moment where skill, patience, and nerve converge into a single frame that feels impossible because it nearly is.

Why hydrogen-alpha matters

Capturing a skydiver against the Sun demands more than luck—it requires wavelength discipline. McCarthy used a hydrogen-alpha filter, passing a razor-thin slice of light around 656.28 nm. This isolates the Sun’s chromosphere, revealing filaments and prominences while suppressing broadband glare that would wash out the silhouette. The narrowband view increases contrast, so Gabriel C. Brown’s outline reads cleanly against dynamic solar textures. It’s a marriage of art and optics: the Sun appears alive, yet the human form remains unmistakable. H-alpha also reduces atmospheric turbulence artifacts, helping stabilize detail at long focal lengths. The result is an image that balances scientific fidelity with graphic punch. Viewers see a star’s surface drama, not a bland white disc—making the human figure feel daring but believable. Without hydrogen-alpha, this photo would lose both clarity and character, turning a historic alignment into a forgettable speck.

Risk, craft, and meaning

Why does this image resonate beyond science circles? It compresses risk, craft, and cosmic scale into one glance. Extreme sport meets astrophotography: timing a human freefall with a celestial target required coordination, trust, and iteration—six flights to nail the pass. The stakes are real, yet safety and clarity prevail through planning, not bravado. Artistically, the Sun’s staggering distance and the human’s fleeting motion spark a dialogue about perspective: our smallness against a star, and our ingenuity in framing it. The title, “The Fall of Icarus,” nods to myth while subverting it—this isn’t hubris punished, but precision rewarded. It shows how technology, teamwork, and patience can turn a ludicrous idea into a documented reality. The image’s virality feels inevitable: it’s visually audacious, technically sound, and emotionally legible—a rare trifecta in modern photography.