Throughout history, countless Black women have stood at the intersection of racial and gender justice, fighting battles on multiple fronts while facing erasure from the very movements they helped build. Their voices challenged slavery, demanded voting rights, created educational institutions, and shaped the legal frameworks we rely on today. Yet textbooks and popular narratives have often buried their contributions beneath the stories of white suffragists and male civil rights leaders. This article shines a light on fifteen extraordinary Black feminists whose courage and brilliance deserve to be remembered and celebrated.

1. Maria W. Stewart (1803–1879)

Back in 1832, Maria W. Stewart did something almost unthinkable for a woman of her time: she stood before mixed audiences of men and women in Boston and spoke boldly about politics, abolition, and women’s rights. Her lectures came decades before the famous Seneca Falls Convention, making her a true pioneer in both Black activism and the women’s movement.

Stewart argued passionately that Black women deserved equality and education. She challenged both racism and sexism with fierce conviction. Her radical ideas upset many male abolitionists who thought women should stay silent.

Because women speaking publicly was considered scandalous and improper, Stewart’s groundbreaking work was largely forgotten. History books skipped over her contributions for generations, even though she blazed trails that others would later follow.

2. Sarah Parker Remond (1826–1894)

Sarah Parker Remond became a celebrity on the antislavery lecture circuit, captivating audiences across America and Europe with her powerful speeches against slavery and for women’s rights. Unlike many activists who stayed close to home, Remond took her message international, building bridges between movements on different continents.

After years of public speaking, she made another remarkable pivot: she moved to Italy and qualified as a physician. This career shift showed her commitment to helping people in multiple ways, combining activism with medical service.

Most U.S. history classes focus only on domestic movements, so Remond’s transatlantic activism fell through the cracks. Her work abroad meant fewer American historians documented her achievements, leaving her contributions largely unknown to students today.

3. Anna Julia Cooper (1859–1964)

In 1892, Anna Julia Cooper published A Voice from the South, a book that connected the dots between race, gender, and education in ways no one had before. Her writing became a cornerstone of Black feminist thought, arguing that society could not progress without uplifting Black women.

Cooper was not just a writer but also an educator who earned a doctorate in her sixties. She dedicated her life to proving that Black women deserved access to higher learning and leadership roles.

Unfortunately, the academic canon of her era focused on white suffragists and male civil rights leaders. Cooper’s scholarship circulated in smaller networks, so mainstream historians overlooked her brilliant contributions for far too long.

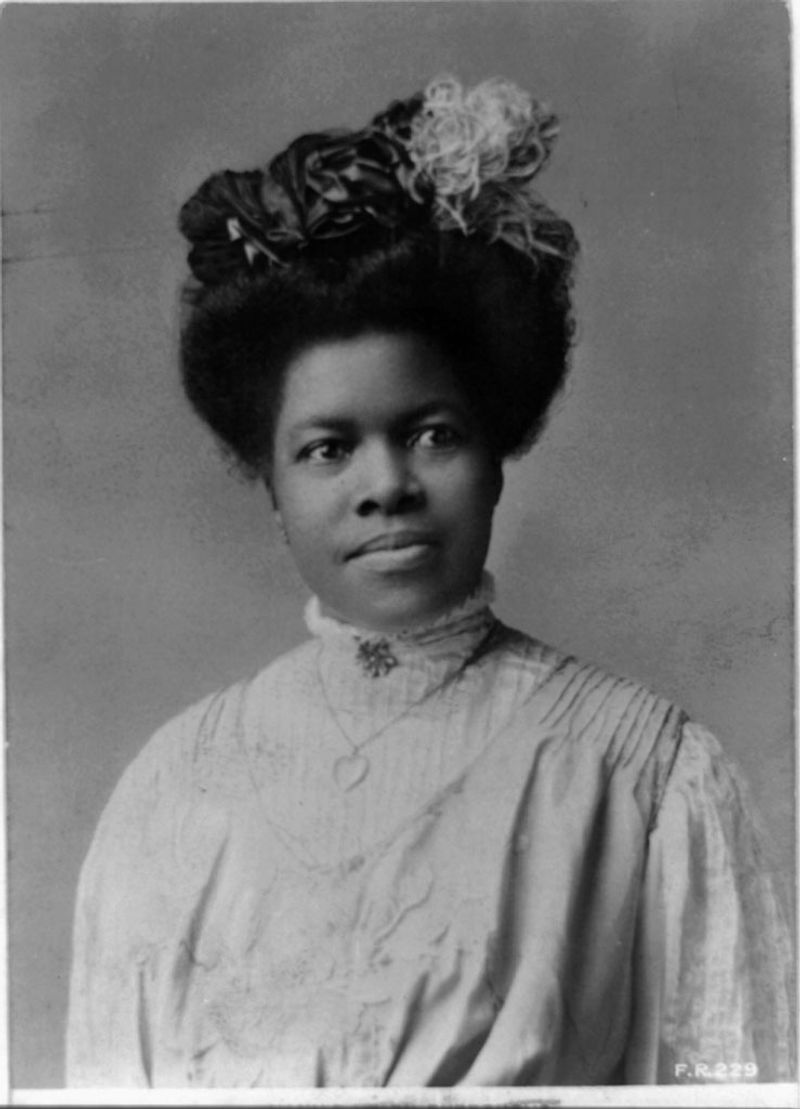

4. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825–1911)

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was a poet, novelist, and fiery orator who traveled the country speaking against slavery and for women’s rights. In 1866, she delivered a landmark speech titled We Are All Bound Up Together, demanding that the suffrage movement include and center Black women rather than leave them behind.

Harper understood that freedom meant nothing if only some women gained the vote. She pushed white suffragists to recognize that racism and sexism were intertwined struggles.

After the Civil War, suffrage histories tended to celebrate white leaders like Susan B. Anthony while erasing Black women speakers. Harper’s crucial role in shaping the movement was sidelined, even though her words challenged the movement to be truly inclusive.

5. Nannie Helen Burroughs (1879–1961)

Nannie Helen Burroughs founded the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, D.C., in 1909, guided by the bold motto We specialize in the wholly impossible. Her school offered both academic and vocational education, preparing Black women for careers and leadership at a time when few institutions welcomed them.

Burroughs believed education was the key to independence and dignity. She refused to wait for white philanthropists to fund her vision, instead building a self-sustaining institution rooted in the Black church community.

Because her school did not fit the typical philanthropic narratives that dominate education histories, it was often left out of textbooks. Burroughs’s remarkable achievements in expanding opportunities for Black women deserve far more recognition than they have received.

6. Pauli Murray (1910–1985)

Pauli Murray was a legal genius who coined the term Jane Crow to describe the double discrimination Black women faced. Murray’s legal theories laid critical groundwork for sex-discrimination law, and arguments Murray developed were later used by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in landmark cases.

Murray co-founded the National Organization for Women, became an Episcopal priest, and challenged gender norms throughout life. Murray’s multidimensional identity as Black, queer, and gender-nonconforming made mainstream narratives uncomfortable.

Mid-century respectability politics and left-leaning views meant Murray was often left uncredited or forgotten. Only recently have historians begun to properly recognize Murray’s massive contributions to civil rights, feminism, and legal theory. Murray’s story reminds us that some of the most important architects of justice remain hidden in plain sight.

7. Anna Arnold Hedgeman (1899–1990)

Anna Arnold Hedgeman was the only woman on the organizing committee for the 1963 March on Washington, and she fought hard to ensure women had visibility on that historic stage. Despite her efforts, the program largely excluded women speakers, a fact she protested publicly.

Hedgeman worked in government, civil rights organizations, and religious institutions throughout her career. She consistently pushed for women’s voices to be heard alongside men’s in the fight for justice.

Because the March on Washington became famous for Dr. King’s speech and other male leaders, Hedgeman’s organizing role was forgotten. Her insistence that women deserved equal recognition was ignored then and erased later. Her story highlights how even landmark moments in history can sideline the women who made them possible.

8. Claudia Jones (1915–1964)

Claudia Jones was a Black communist feminist who wrote the groundbreaking 1949 essay An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman! Her writing connected race, class, and gender oppression in ways that anticipated later intersectional theory by decades.

Jones was deported from the United States during the Cold War because of her communist activism. She moved to London, where she organized early Caribbean carnivals that eventually became the famous Notting Hill Carnival.

Cold War repression erased Jones from mainstream American memory, and her radical politics made her an inconvenient figure for historians to celebrate. Her transnational activism and communist affiliation meant she was deliberately forgotten. Only recently have scholars begun reclaiming her vital contributions to Black feminist thought.

9. The Combahee River Collective (founded 1974; statement 1977)

The Combahee River Collective, founded by Barbara Smith, Beverly Smith, Demita Frazier, and others, articulated a holistic analysis of interlocking oppressions that shaped activism for generations. Their 1977 statement introduced the concept of identity politics as a tool for liberation, not division.

The collective argued that fighting one form of oppression while ignoring others was doomed to fail. They centered the experiences of Black queer women and connected struggles against racism, sexism, capitalism, and homophobia.

Their queer, socialist, grassroots orientation placed them outside mainstream feminist and civil rights narratives. The Collective’s radical vision was too threatening to be easily absorbed into popular histories. Today, their statement is studied widely, but their names remain less known than they should be.

10. Olive Morris (1952–1979)

Olive Morris was a British Black feminist and community organizer who co-founded the Brixton Black Women’s Group and the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent. She fought tirelessly against police brutality, housing injustice, and for Black women’s autonomy in the UK.

Morris was fearless in confronting authority and built networks of support for marginalized communities. Her activism connected local struggles in Brixton to global movements for liberation.

Morris died tragically young at just 27 years old, cutting short a brilliant organizing career. UK grassroots women’s movements are under-documented compared to their American counterparts, so Morris’s contributions were largely forgotten. Only recently have British activists and historians begun reclaiming her legacy and honoring her courage.

11. Dovey Johnson Roundtree (1914–2018)

Dovey Johnson Roundtree was a civil rights attorney whose 1955 victory in Keys v. Carolina Coach struck a major blow against segregation in interstate bus travel. Her Interstate Commerce Commission ruling came before the more famous Supreme Court cases, yet it is rarely taught in schools.

Roundtree was also one of the first Black women to be ordained in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. She combined legal advocacy with spiritual leadership throughout her long life.

Because her landmark case was decided by an administrative forum rather than the Supreme Court, it did not receive the same attention as other desegregation victories. Roundtree’s brilliant legal strategy and historic win deserve far more recognition. Her story shows that justice can be won in many venues, not just famous courtrooms.

12. Esther Cooper Jackson (1917–2022)

Esther Cooper Jackson was the founding editor of Freedomways magazine, which ran from 1961 to 1985 and served as the intellectual hub of Black left feminism and anticolonial thought. The journal nurtured generations of movement writers and connected struggles across the African diaspora.

Jackson understood that movements needed spaces for deep thinking and debate, not just action. Freedomways published essays, poetry, and analysis that shaped how activists understood their work.

Editors and institution-builders are often invisible in histories that focus on charismatic leaders and dramatic events. Jackson’s crucial role in creating intellectual infrastructure for the movement was overlooked for decades. Her legacy reminds us that publishing and editing are forms of activism that sustain movements over time.