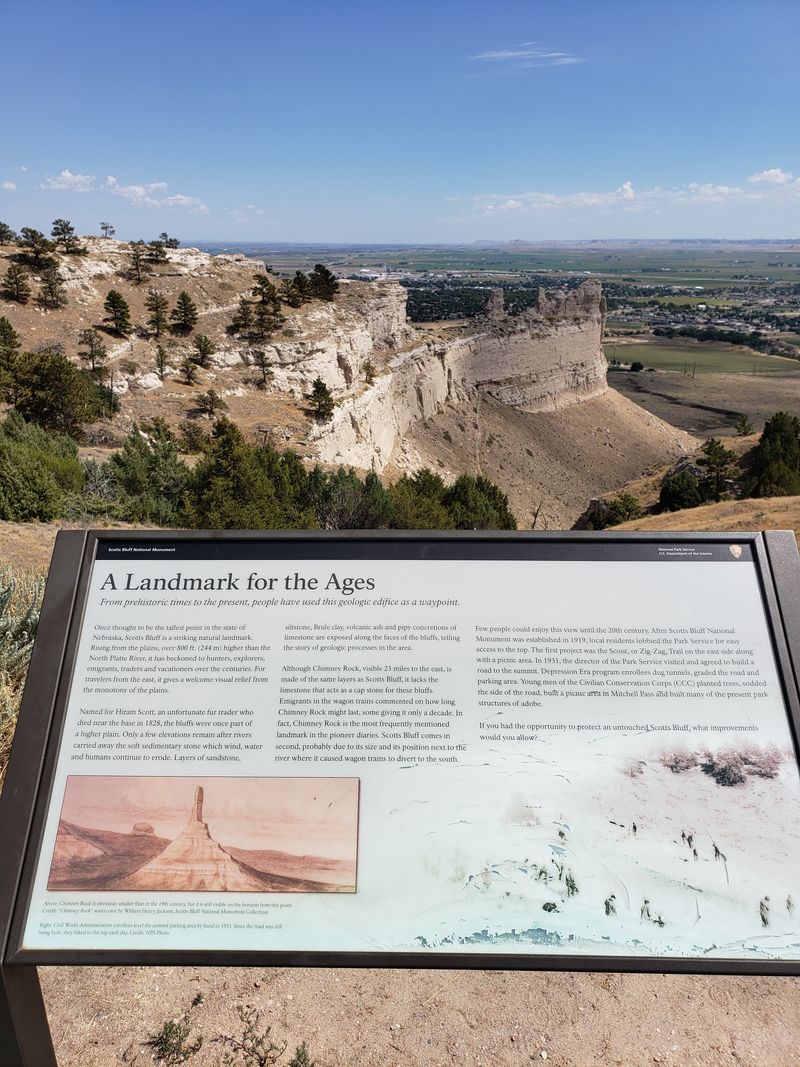

Stand at the edge of the High Plains and you will see why travelers once breathed easier at first sight of this bluff. It towers above the North Platte River, a natural compass pointing west when maps were scarce and hope was everything. Today, you can follow the same ground and feel the pull of the horizon. Ready to see how a rock face became a nation’s waypoint?

Picture wagons creaking toward a sandstone wall that refuses to be ignored. More than 250,000 emigrants passed this way between 1843 and 1869, reading the landscape like scripture. When you approach Scotts Bluff, you feel that same surge of recognition, a landmark that says keep going.

You can walk near preserved trail traces and sense the momentum of a continent in motion. Interpretive panels translate ruts and ridgelines into stories. Stand still, let the wind carry hoofbeats and voices forward, and you will understand why this bluff became the West’s unforgettable milepost.

It was not just Oregon-bound dreamers who watched for this skyline. California gold seekers and Mormon handcart companies also used Scotts Bluff as a navigation beacon, steering through the prairie sea with a fixed point ahead. Here, routes braided together, then fanned apart as choices hardened into futures.

Walking the paths today, you trace those intertwined journeys with your own steps. Trail markers and exhibits explain the diverging destinations that began from a shared landmark. Look up at the cliffs, and you will see a crossroads written in stone, pointing three ways at once.

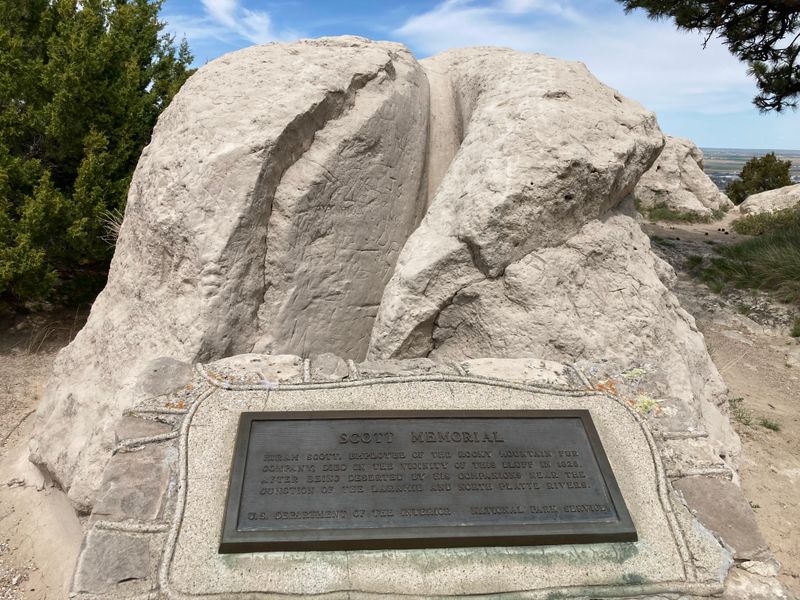

Hiram Scott’s name clings to these cliffs like a whisper across time. A clerk for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, he died near here in 1828 under circumstances still debated. Was it illness, abandonment, or simply the land’s hard calculus. You can stand beneath the bluffs and feel the unanswered questions.

Interpretive displays unpack the fur trade’s rough economy and Scott’s lingering legacy. The geography lends drama, turning biography into legend. When the evening light strikes the sandstone, you may catch yourself imagining footprints on the riverbank, and a name etched forever into Nebraska’s skyline.

Set just west of Gering in Nebraska’s Panhandle, the monument anchors a landscape of big skies and long horizons. The North Platte River sweeps nearby, feeding farms, cottonwoods, and the same corridor pioneers followed. When you arrive, the shift is immediate: prairie openness, sandstone mass, town life tucked close.

It is easy to navigate from downtown Gering or Scottsbluff to the monument’s entrance. With clear signage and park maps, you can orient yourself fast. Location matters here, because this bluff was geography turned guidance, a waypoint that stitched local place into national movement.

Scotts Bluff National Monument protects roughly 3,000 acres where history and habitat meet. You can wander from shortgrass swales to broken badlands, then up toward the cliffs that define the skyline. The scale is large enough to breathe but intimate enough to read details in the ground.

Rangers have curated routes that help you sample the acreage with purpose. One hour or all day, there is room for your pace. Every acre tells a chapter: trail ruts, prairie blooms, fossil bearing sediments. The monument’s boundaries are lines drawn to gather stories like wind gathers seed.

The bluffs rise about 800 feet above the North Platte River, and your neck tilts back instinctively. Layered sandstone and siltstone tell time by color: tawny, rust, ash. Erosion carved ribs and alcoves that catch light like sculpture. Up close, the stone feels both fragile and stubborn.

Photographers love the edges that glow at sunrise and flame at sunset. You will notice swallows, shifting shadows, and the sense that the rock keeps breathing. These cliffs are not a wall so much as a gallery, each ledge curating centuries of wind’s patient work.

Early travelers detoured widely around the obstacle until Mitchell Pass became the workable corridor. Threading between the bluffs, it shortened mileage and risk, funneling thousands through a dramatic stone hallway. Walk or drive near the pass and you will grasp how terrain negotiates with ambition.

Interpretive signs lay out before and after: longer detours versus the pass’s efficient cut. Today, the route feels calm, but echoes remain in the ruts and benches. Mitchell Pass turned a geographic problem into a practical solution, proving that smart pathfinding can tame even monumental stone.

Start at the visitor center and the whole place clicks into focus. Exhibits weave pioneer diaries, trail artifacts, and geologic timelines into a story you can touch. Kids press buttons, adults linger at maps, and everyone finds a voice that sounds like someone they know.

Rangers add context with programs and personal tips. Temporary displays rotate fresh angles on migration, ecology, and local communities. When you step back outside, the bluffs feel newly fluent, as if they taught you a few words of their language. The gift shop sends you on with field guides and postcards.

A paved Summit Road climbs the bluff in switchbacks and tunnels, unveiling wider views with every bend. You can drive to the top, step out at overlooks, and watch the river valley spread like a map. On clear days, the horizon feels almost curved with distance.

Safety rails, parking, and signage keep it easy. Bring a light jacket, because breezes sharpen at elevation. Sunset throws ribbons of color across the valley, and you will not be the only one lingering. The road turns a daunting ascent into a scenic ritual you will replay in memory.

Trails here are time machines you operate with your feet. The Oregon Trail Pathway traces wagon routes, while the Summit and Saddle Rock Trails thread viewpoints and geology lessons. You set your pace, hear larks, and measure distance in stories per mile.

Bring water, sturdy shoes, and curiosity. Grades vary, but wayfinding is straightforward, and benches offer breathers with views. Each step presses your present into layers of past travel. By the end, your legs remember inclines, and your mind holds names and dates that suddenly feel personal, because you carried them yourself.

Before wagons, there were volcanoes far away and sediments close at hand. Layers at Scotts Bluff preserve 20 to 33 million years of geologic history, ash beds tucked among sandstones and siltstones. Fossil fragments whisper of ancient ecosystems that predate any human route decisions.

Interpretive panels decode the stripes and hues. You can match a line in the cliff to an epoch on the timeline, translating color into time. Geology turns the bluff into a library where pages will not stay still. Wind keeps flipping them, and you keep wanting to read more.

Between the river and the cliffs stretches a mosaic of mixed grass prairie and rugged badlands. You will notice cracked clay, scattered yucca, and bursts of seasonal wildflowers. This is the in-between world emigrants crossed, harsh and beautiful, full of small dramas in the wind.

Stay on trails to protect fragile soils. Listen for meadowlarks, watch for pronghorn at the edges, and scan for hawks surfing thermals. The ecosystem’s resilience shows in textures and scents, from sun warmed grasses to cool shade under cottonwoods. It frames the bluffs like a natural prologue.

Look down from the summit and you will spot Gering and Scottsbluff stitched along the North Platte. These communities matured where routes, water, and opportunity converged. Railroads, agriculture, and later highways followed the same logic the pioneers used: go where the valley guides you.

Museums, murals, and local festivals nod to trail heritage without freezing the towns in time. You can grab coffee, then drive minutes to stand inside history. The relationship is ongoing: modern life humming under ancient cliffs. It feels right that the landmark still watches over daily routines and long term plans.

On December 12, 1919, the nation drew a protective circle around this place. The designation as a national monument recognized both cultural and geologic significance. You can thank that decision every time you round a bend and find an unspoiled vista waiting.

Archival photos inside the visitor center show early facilities and proud locals. Over a century later, management balances preservation with access, keeping roads, trails, and programs in good shape. The date feels like a promise kept, a century long handshake that lets you meet the past without rushing it.

Planning ahead makes your visit smoother. The monument typically operates 8:30 AM to 4:30 PM, with current details at nps.gov/scbl or by calling +1 308-436-9700. You can navigate to 190276 Old Oregon Trail, Gering, NE 69341, and follow signs to the Summit Road and visitor center.

Check weather, as wind and storms can affect access. Bring water, sun protection, and layers, because conditions shift quickly on the heights. Parking is straightforward, and trail maps are available inside. Respect closures for wildlife or maintenance, and you will find everything else welcomes you right in.

Stand at the overlook and the sweep of history lands in your chest. This bluff is a living reminder of westward expansion’s grit and gamble, the hopes that pushed families across a continent. You may feel awe, but also empathy for the cost embedded in those journeys.

Today, voices at the monument include many perspectives. Exhibits and programs invite you to consider Indigenous homelands, settler ambition, and environmental change together. When you leave, the cliffs travel with you as a compass of memory, pointing toward a more thoughtful kind of west.