Have you ever looked at a map and wondered why Iceland seems so green while Greenland is mostly covered in ice? The names appear completely backwards!

Vikings who discovered these lands over a thousand years ago gave them these puzzling names, and the reasons behind their choices are fascinating. Understanding these stories reveals clever marketing tricks, tragic winters, and how our climate has changed over the centuries.

15. The Confusing Names

<p>Looking at pictures from space, you would think someone made a terrible mistake labeling these two islands. Iceland shows up with lush green valleys and coastal areas, while Greenland appears as a massive white sheet of ice.

The contrast is so obvious that kids often ask their teachers if the names got switched by accident.</p><p>Geography textbooks spend entire pages explaining this puzzle to confused students. Maps clearly show that Iceland has far more vegetation and milder weather patterns.

Meanwhile, Greenland remains buried under one of the world’s largest ice sheets.</p><p>Scientists estimate that over 80 percent of Greenland stays frozen year-round. Iceland, on the other hand, enjoys relatively warm temperatures thanks to ocean currents.

This geographical irony has puzzled travelers and students for generations.</p><p>Viking explorers from over a thousand years ago created these misleading names.

Their reasons mixed truth, deception, and unfortunate timing into one confusing legacy.</p>

14. A Viking Marketing Strategy

<p>Vikings were not just fierce warriors and skilled sailors. They also understood how to attract people to new settlements using clever persuasion.

Naming a frozen island something appealing while giving a greener land a cold-sounding name might seem backwards, but it served specific purposes.</p><p>Early settlers worried that too many people moving to Iceland would strain limited resources. A harsh-sounding name could slow down immigration and prevent overcrowding.

Greenland, however, desperately needed colonists to survive as a Viking outpost.</p><p>Historical records suggest Vikings deliberately chose names as promotional tools. This represents one of the earliest examples of location branding in human history.

Modern marketing experts would recognize these tactics as classic advertising strategies.</p><p>The approach worked remarkably well for centuries. Greenland attracted enough settlers to establish lasting communities.

Meanwhile, Iceland developed at a more controlled pace that matched its agricultural capacity.</p>

13. Erik the Red’s Choice

<p>Around 982 AD, a Viking outlaw named Erik the Red sailed west from Iceland after being banished for murder. He discovered a massive island and spent three years exploring its coastline.

When his exile ended, Erik faced a critical challenge: convincing others to join him in colonizing this remote land.</p><p>Erik deliberately chose the name Greenland to make the island sound inviting and fertile. He openly admitted that an attractive name would encourage people to move there.

This honest manipulation shows how Vikings valued practical results over strict truthfulness.</p><p>His strategy succeeded beyond expectations. Hundreds of settlers followed Erik back to Greenland, establishing farms along the southwestern coast.

These communities survived for nearly 500 years before mysteriously disappearing.</p><p>Erik the Red became one of history’s most successful real estate promoters.

His naming choice created lasting confusion but achieved its immediate goal perfectly.</p>

12. Iceland’s Icy Reputation

<p>A Viking named Flóki Vilgerðarson earned the nickname Hrafna-Flóki, meaning Raven-Flóki, because he used ravens to navigate across the ocean. When he arrived at the island around 860 AD, he climbed a tall mountain and saw fjords completely filled with floating ice.

This sight deeply impressed him.</p><p>Flóki’s first winter turned into an absolute disaster. Harsh weather killed all his livestock, and his family barely survived.

Bitter from his experience, he decided the island deserved a name reflecting its cruel, frozen nature.</p><p>He called it Iceland, and the name stuck despite protests from other settlers. Many Vikings who came later found the island much more hospitable than Flóki’s name suggested.

They discovered green pastures, fish-filled waters, and workable farmland.</p><p>Flóki’s unfortunate timing and bad luck gave Iceland a reputation that does not match most people’s actual experience living there.</p>

11. Þórólfur’s Optimism

<p>Not every Viking agreed with Flóki’s negative assessment of Iceland. Another settler named Þórólfur had a completely different experience exploring the same island.

He found rich fishing grounds, fertile valleys, and abundant wildlife that could support permanent communities.</p><p>Þórólfur actively promoted Iceland as a land of opportunity back in Norway and other Viking territories. He described lush pastures perfect for sheep and cattle.

His enthusiastic reports convinced many families to pack their belongings and sail west.</p><p>This created an interesting contradiction where the island’s official name suggested harsh conditions while word-of-mouth testimonials painted a welcoming picture. Prospective settlers had to decide which version to believe.

Many chose to trust Þórólfur’s optimistic account.</p><p>Iceland’s population grew steadily despite its intimidating name. Þórólfur’s positive publicity campaign proved that personal recommendations often outweigh official labels when people make life-changing decisions.</p>

10. Iceland Was Once Greener

<p>Ocean currents play a massive role in determining climate patterns across the North Atlantic. Iceland benefits enormously from the Gulf Stream, a powerful current that carries warm water from tropical regions northward.

This natural heating system raises temperatures around Iceland by approximately 6 degrees Celsius compared to similar latitudes.</p><p>Without the Gulf Stream, Iceland would indeed live up to its frozen name. The island sits just below the Arctic Circle where temperatures should be much colder.

Instead, coastal areas rarely experience extreme cold, and grass grows throughout much of the year.</p><p>Greenland receives no such benefit from warm ocean currents. Cold Arctic waters surround most of the island, keeping temperatures low year-round.

This geographical accident of ocean circulation explains much of the naming confusion.</p><p>Climate scientists study these patterns to understand how ocean temperatures affect weather worldwide.

Iceland serves as a perfect example of how currents can transform an island’s livability.</p>

9. Greenland in Summer

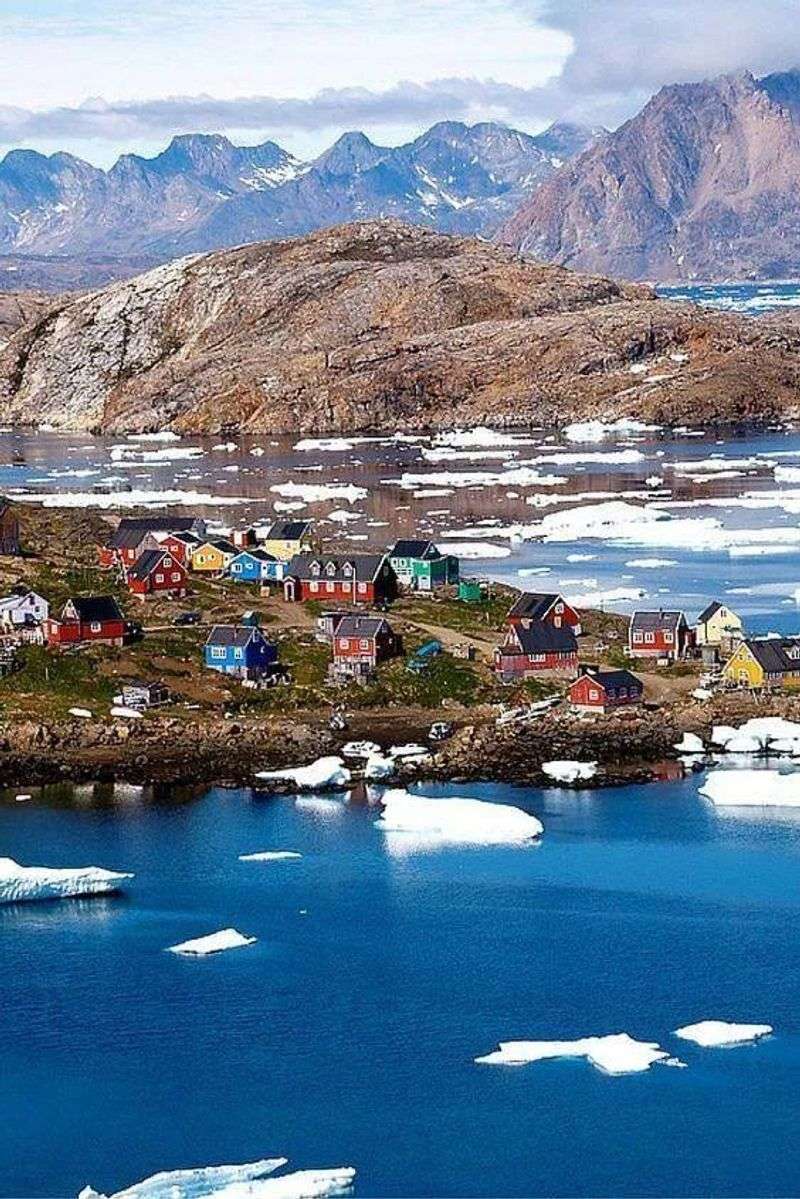

<p>During brief summer months, Greenland’s southern coastline transforms dramatically. Ice melts back to reveal rocky soil, hardy grasses, and even some flowering plants.

This seasonal greenery justified Erik the Red’s naming choice, at least partially. When Vikings first arrived, they saw these summer landscapes and recognized farming potential.</p><p>Modern measurements confirm that over 80 percent of Greenland remains permanently covered by ice sheets.

Only narrow coastal strips become ice-free during warmer months. These limited areas supported small Viking settlements for several centuries.</p><p>Archaeological excavations have uncovered Viking farms along Greenland’s southwestern coast.

Settlers built stone houses, raised livestock, and grew limited crops. Their communities remained small but functional within these environmental constraints.</p><p>Summer visitors to Greenland today can still see the same green patches that impressed Viking explorers.

The name makes perfect sense for a few weeks each year before winter returns.</p>

8. Farming in Greenland

<p>Viking settlers in Greenland successfully grew potatoes and raised sheep in the southwestern regions. These areas lie farther south than most of Iceland, giving them slightly longer growing seasons.

Farmers took advantage of every warm day to cultivate crops and gather hay for winter animal feed.</p><p>Archaeological evidence shows that Greenland Vikings maintained herds of sheep, goats, and cattle. They built stone barns to protect animals during harsh winters.

Sheep provided wool for clothing and trading, while dairy products supplemented diets based mainly on fish and seal meat.</p><p>Potato cultivation represented an important achievement in such a challenging environment. These hardy vegetables could survive cool temperatures and provided essential nutrition.

Modern Greenlandic farmers continue some of these traditional practices in the same coastal areas.</p><p>The Viking farming communities eventually collapsed around 1450 AD. Climate cooling, soil depletion, and isolation from Europe all contributed to their disappearance.

Their agricultural legacy remains visible in ruins scattered across the landscape.</p>

7. Vatnajökull Glacier

<p>Iceland hosts Europe’s largest glacier, called Vatnajökull, which covers an area roughly equal to the entire island of Puerto Rico. This massive ice cap dominates southeastern Iceland and contains numerous volcanic systems beneath its frozen surface.

The combination of ice and fire creates spectacular geological features.</p><p>Vatnajökull’s ice reaches thicknesses of up to 1,000 meters in some locations. Glacial rivers flow from underneath, carrying meltwater to the ocean.

These rivers change course frequently, creating dangerous floods called jökulhlaups when volcanic heat melts ice from below.</p><p>Tourists visit Vatnajökull National Park to see ice caves, glacial lagoons, and stunning ice formations. The glacier has retreated noticeably over the past century due to rising temperatures.

Scientists monitor its shrinkage as an indicator of climate change.</p><p>This enormous glacier reminds visitors that Iceland’s name does have some basis in reality.

While much of the island stays green, significant portions remain frozen year-round.</p>

6. Naddador’s Snæland

<p>Before Flóki gave Iceland its current name, the very first Nordic explorer to reach the island called it something different. A Swedish Viking named Naddador accidentally discovered Iceland around 850 AD when storms blew his ship off course during a voyage to the Faroe Islands.</p><p>When Naddador landed, snow covered the ground as far as he could see.

Impressed by the white landscape, he named the island Snæland, which translates directly to Snow Land. This name seemed perfectly logical based on his winter arrival.</p><p>Naddador did not stay long enough to see the island during other seasons.

He sailed away after a brief exploration, spreading stories about Snæland back in Scandinavia. His name never became official because later explorers spent more time there and offered different perspectives.</p><p>If Naddador’s name had stuck, we might today call the island Snow Land instead of Iceland.

Either way, the frozen theme would have continued confusing people about the island’s true character.</p>

5. Gardar Svavarsson

<p>A Swedish Viking named Garðar Svavarsson became the second Nordic explorer to reach Iceland, arriving shortly after Naddador. Garðar took a much more thorough approach to exploration, sailing completely around the island to map its coastline.

This journey proved that Iceland was indeed an island and not connected to any mainland.</p><p>Garðar spent an entire winter on the northern coast at a place called Húsavík. He built shelters and survived the cold months, gaining valuable experience about living conditions.

When spring arrived, he prepared to return to Sweden with detailed reports.</p><p>Before leaving, Garðar named the island Garðarshólmur, meaning Gardar’s Island, claiming it for himself. One of his men chose to stay behind, becoming possibly the first permanent Nordic resident.

Garðar’s name never gained widespread acceptance.</p><p>Later explorers ignored Garðar’s naming attempt and eventually settled on Iceland.

His detailed circumnavigation provided crucial information that helped future settlers, even if his chosen name disappeared from history.</p>

4. Flóki’s Tragic Winter

<p>Flóki Vilgerðarson’s decision to name Iceland came from deep personal tragedy rather than simple observation. During his disastrous first winter, he lost his beloved daughter to the harsh conditions.

Grief and anger overwhelmed him as he also watched all his livestock die from starvation and cold.</p><p>These combined losses destroyed Flóki’s initial optimism about settling the new land. He blamed the island itself for his family’s suffering.

When spring finally arrived, Flóki had developed intense bitterness toward the place that had cost him so much.</p><p>Choosing the name Iceland represented his emotional response to personal catastrophe. Other settlers who arrived better prepared and during favorable seasons had completely different experiences.

They found the island much more welcoming and survivable.</p><p>Flóki eventually returned to Iceland and lived there successfully for many years. His harsh name remained despite his changed opinion.

This shows how first impressions, especially tragic ones, can create lasting labels.</p>

3. Viking Settlement Names

<p>Early Icelandic settlers developed a strong identity centered on their new home. They called themselves Íslendingur, which translates to people from Iceland.

This name connected them to their adopted land while maintaining links to their Nordic heritage and culture.</p><p>Using this self-designation helped create unity among settlers who came from different parts of Scandinavia. Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes all became Íslendingur once they established farms in Iceland.

The shared identity proved stronger than old regional differences.</p><p>Modern Icelanders still use this term with pride. The word appears in official documents, cultural discussions, and everyday conversation.

It represents over a thousand years of continuous settlement and cultural development.</p><p>Language experts note that Icelandic remains remarkably similar to Old Norse because of the island’s isolation. Modern Icelanders can read ancient Viking sagas with less difficulty than Norwegians or Swedes.

This linguistic continuity strengthens their connection to Viking ancestors who first called themselves Íslendingur.</p>

2. Greenland’s Original Climate

<p>Scientists studying ancient ice cores and fossilized shellfish have discovered that southern Greenland experienced significantly warmer temperatures between 800 and 1300 AD. This period coincides almost perfectly with Viking settlement attempts.

The timing was not accidental but rather shows Vikings took advantage of favorable climate conditions.</p><p>During this Medieval Warm Period, Greenland’s coastal areas received less sea ice and enjoyed longer growing seasons. Summer temperatures reached several degrees higher than today’s averages.

These conditions made Erik the Red’s promotional name Greenland surprisingly accurate for the time.</p><p>Archaeological evidence supports the climate data. Viking farms existed in locations that would be impossible to cultivate today.

Pollen samples show crops and grasses that need warmer conditions than currently exist.</p><p>When temperatures dropped during the Little Ice Age starting around 1300 AD, Greenland became much harsher. Viking settlements struggled and eventually disappeared.

The name Greenland became increasingly misleading as ice expanded across formerly habitable areas.</p>

1. Future Climate Changes

<p>Climate scientists report that Greenland’s ice sheet is melting at an accelerating rate due to global warming. Temperatures in the Arctic region are rising twice as fast as the global average.

This rapid change means Greenland might eventually become greener again, making its Viking name more appropriate than it has been for centuries.</p><p>Meanwhile, Iceland continues enjoying relatively mild temperatures thanks to the Gulf Stream. However, some climate models suggest this crucial ocean current could weaken or shift patterns.

Such changes might actually make Iceland colder despite overall global warming trends.</p><p>The ironic possibility exists that these two islands might eventually swap climate characteristics. Greenland could develop more ice-free land while Iceland experiences harsher conditions.

This would complete a full circle back to when Erik the Red and Flóki first chose their misleading names.</p><p>These climate shifts demonstrate how naming based on current conditions can become outdated.

The Viking naming confusion teaches modern people that environmental conditions constantly change over time.</p>