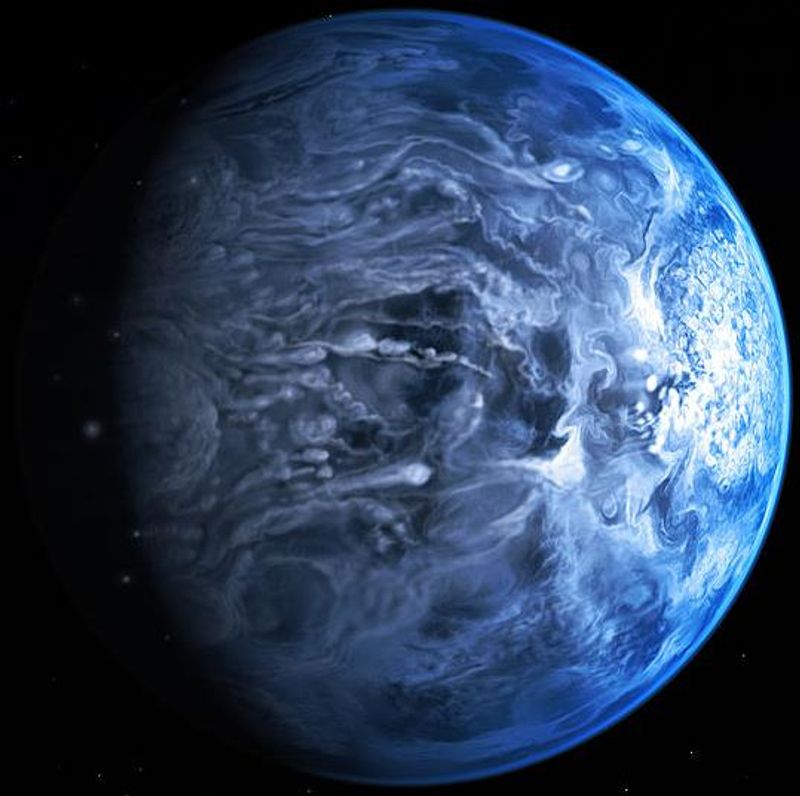

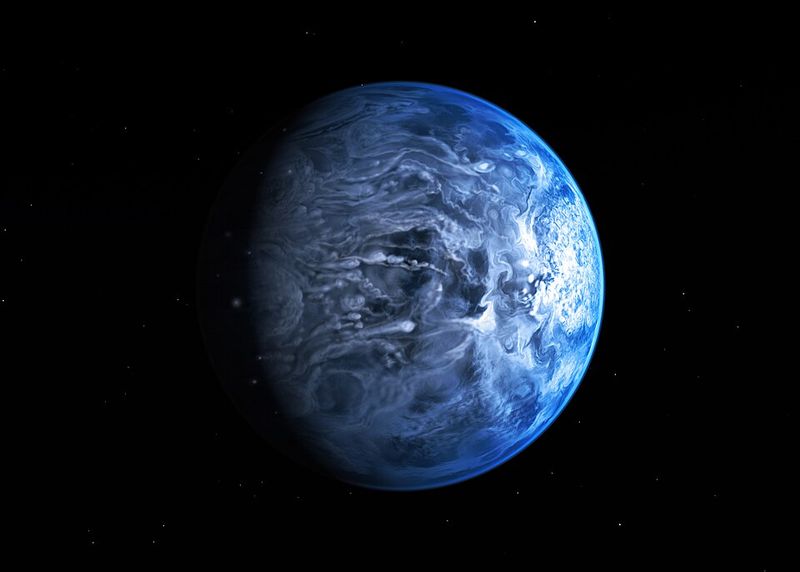

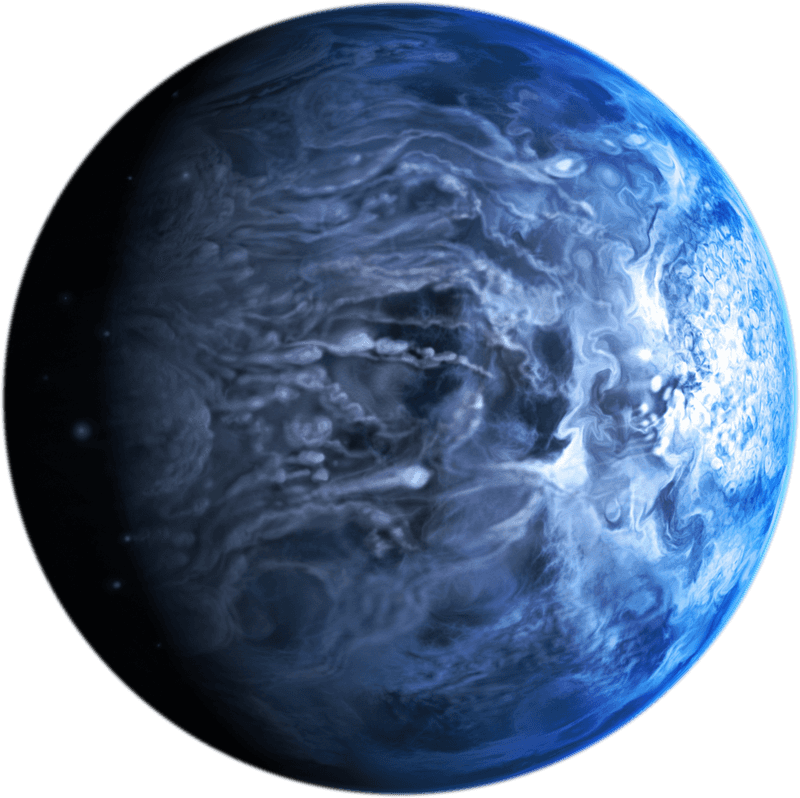

Space is full of surprises, and one of the strangest discoveries is a planet that looks like Earth from far away but is actually a nightmare world. NASA found a blue planet called HD 189733 b that seems peaceful at first glance, but it hides deadly secrets.

Instead of gentle rain and calm skies, this distant world has storms made of glass particles flying sideways at thousands of miles per hour. Scientists study this extreme planet to understand how wild and dangerous weather can get beyond our solar system.

1. ‘New Earth’ is a headline, not a classification

When news outlets first shared images of HD 189733 b, many people got excited thinking scientists had found another Earth. The blue color and round shape made it look familiar, almost like a twin of our home planet.

Headlines screamed about a “new Earth,” sparking hope for a habitable world.

But astronomers quickly set the record straight. This planet is nothing like Earth in terms of size, surface, or the ability to support life.

It belongs to a category called “hot Jupiters,” which are massive gas giants that orbit extremely close to their stars.

Unlike Earth, which has solid ground, oceans, and breathable air, HD 189733 b is a swirling ball of gas with no surface to stand on. The comparison to Earth stops at color alone.

Calling it a “new Earth” is misleading and ignores the violent, hostile conditions that define this world.

The media loves catchy headlines, but this one created confusion. Understanding what this planet truly is helps us appreciate the vast diversity of worlds beyond our solar system and reminds us that not every blue planet is friendly or familiar.

2. What it actually is: a hot, close-orbiting gas giant

HD 189733 b falls into a special category of exoplanets that astronomers call “hot Jupiters.” These are gas giants similar in composition to Jupiter, but they orbit incredibly close to their parent stars. The proximity creates extreme temperatures and bizarre atmospheric conditions that our solar system never experiences.

NASA measurements show this planet has a radius about 1.13 times larger than Jupiter, making it slightly bigger than our solar system’s largest planet. Its mass is also comparable, confirming it as a true giant with no solid surface.

Everything about its structure screams “gas giant,” from its composition to its density.

The “hot” part of “hot Jupiter” comes from its tight orbit around its star. While Jupiter in our solar system stays cold and distant from the Sun, HD 189733 b practically hugs its star.

This closeness heats the planet to furnace-like temperatures, creating weather patterns that would be impossible on a cooler world.

Understanding this classification helps scientists predict what conditions might exist on similar planets. Hot Jupiters challenge our assumptions about planetary formation and show that solar systems can arrange themselves in wildly different ways than ours did.

3. It’s relatively ‘nearby’ in cosmic terms

In the vastness of space, distance takes on a whole new meaning. HD 189733 b sits approximately 64 to 65 light-years away from Earth, which sounds impossibly far.

To put that in perspective, light traveling at 186,000 miles per second would take more than six decades to reach us from there.

Yet astronomers consider this planet relatively close compared to many other exoplanets discovered so far. Some exoplanets lie thousands of light-years away, making them extremely difficult to study in detail.

Being only 65 light-years away puts HD 189733 b in our cosmic neighborhood, at least by astronomical standards.

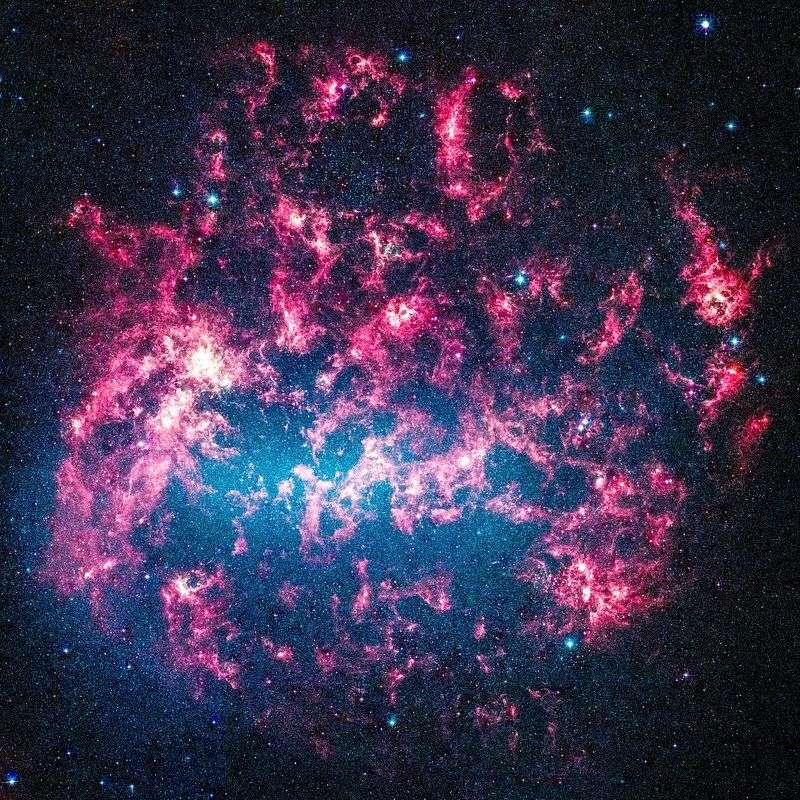

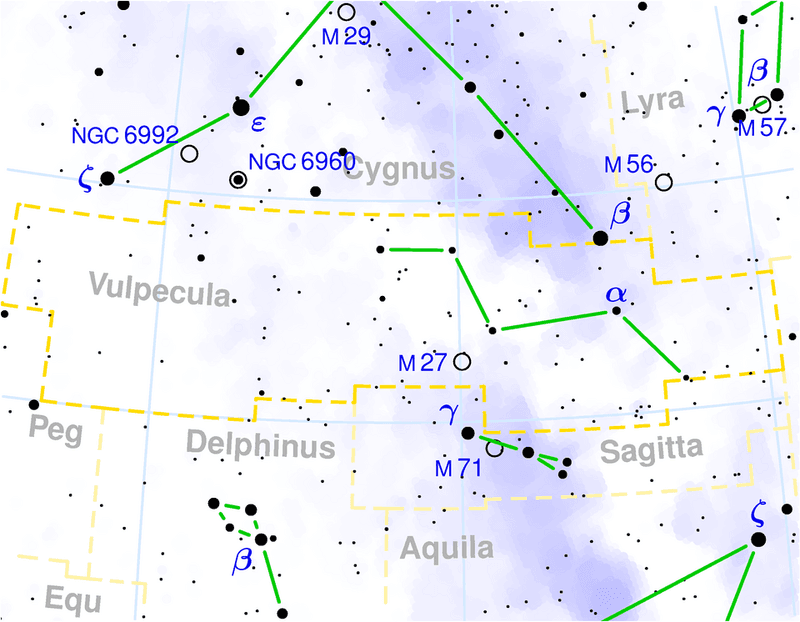

The planet resides in the constellation Vulpecula, which translates to “little fox” in Latin. This small constellation sits in the northern sky and doesn’t contain many bright stars, making it less famous than others.

Still, it now holds one of the most studied exoplanets in astronomy.

This relative closeness allows scientists to use powerful telescopes to analyze the planet’s atmosphere, measure its temperature, and track its orbit with precision. Without this advantage, we might never have learned about the glass storms and extreme winds that make HD 189733 b so fascinating and terrifying at the same time.

4. It wasn’t just discovered – scientists have been studying it for years

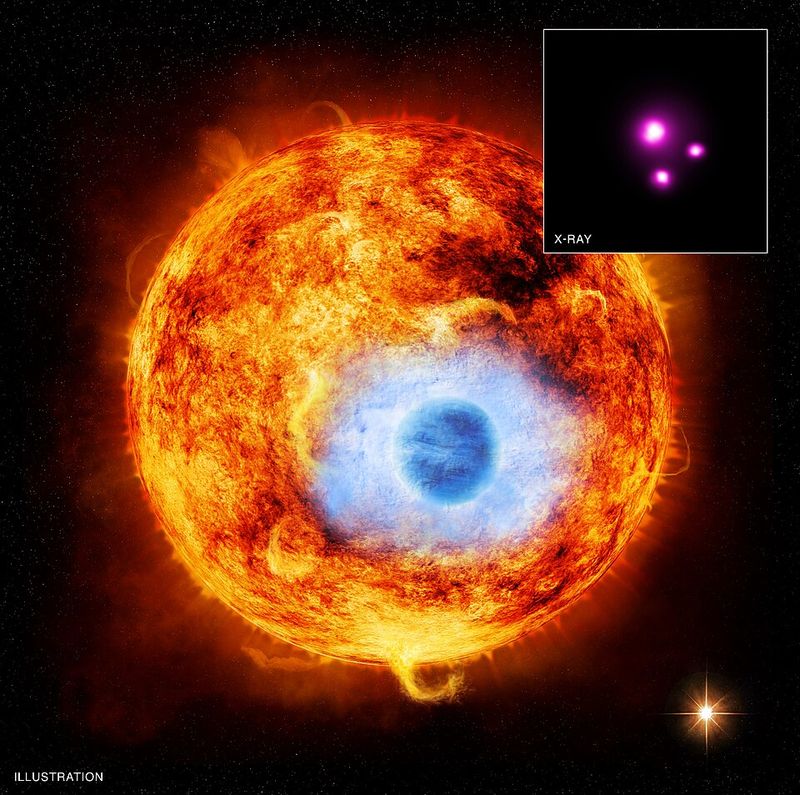

HD 189733 b first entered the scientific record in 2005 when astronomers confirmed its existence using the transit method. This technique involves watching a star’s light dim slightly as a planet passes in front of it, revealing the planet’s presence.

The discovery opened up a whole new chapter in exoplanet research.

Since that initial finding, this planet has become one of the most frequently observed exoplanets in the sky. Researchers return to it again and again because it offers ideal conditions for study.

Its size, brightness, and proximity make it easier to gather detailed data compared to more distant or smaller worlds.

Over nearly two decades, scientists have mapped its atmosphere, measured its temperature, analyzed its chemical composition, and tracked its weather patterns. Each observation adds another piece to the puzzle, helping astronomers understand how such extreme planets form and evolve.

The long study period means we know more about HD 189733 b than most other exoplanets.

This ongoing research proves that discovering a planet is just the beginning. The real work happens over years of careful observation, data collection, and analysis.

HD 189733 b continues to teach us new lessons about planetary science, atmospheric dynamics, and the incredible variety of worlds that exist beyond our solar system.

5. One ‘year’ there lasts only a couple of days

Celebrating a birthday every two days would be reality on HD 189733 b because the planet completes one full orbit around its star in just 2.2 Earth days. This incredibly short orbital period means the planet races around its star at speeds that dwarf anything in our solar system.

For comparison, Earth takes 365 days to circle the Sun once, and even Mercury, our fastest planet, needs 88 days. HD 189733 b’s year is almost 40 times shorter than Mercury’s, showing just how tightly it hugs its parent star.

This breakneck speed is a direct result of the planet’s extremely close orbit.

The rapid orbit creates unusual effects on the planet’s atmosphere and weather systems. Winds don’t have time to settle into stable patterns, and heat distribution becomes chaotic.

One side of the planet constantly faces the star while the other remains in darkness, creating extreme temperature differences that drive violent atmospheric motion.

This short orbital period makes HD 189733 b an excellent target for repeated observations. Astronomers can watch multiple “years” pass in just a week, gathering data much faster than they could with planets that have longer orbits.

Every quick lap around its star provides fresh opportunities to study this fascinating and deadly world.

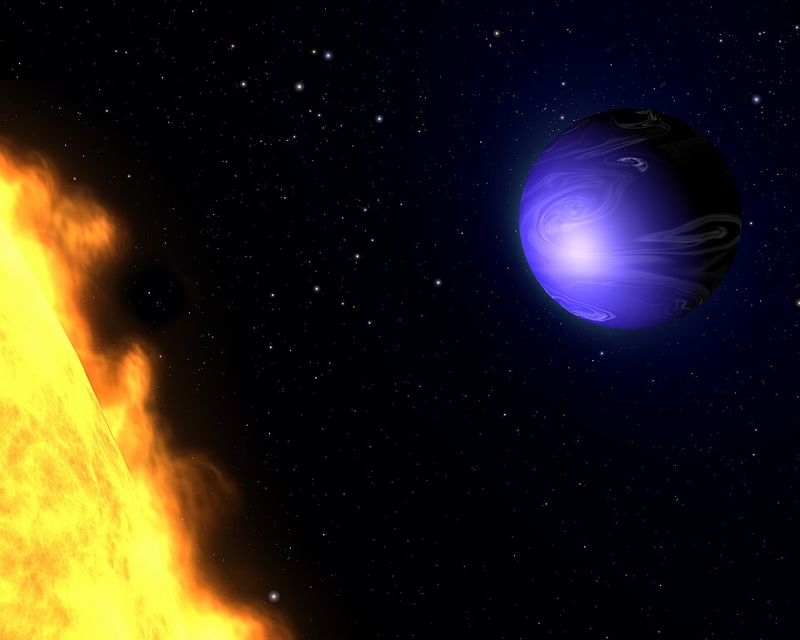

6. It orbits dangerously close to its star

HD 189733 b practically skims the surface of its star, orbiting at a distance that would place it well inside Mercury’s orbit if it were in our solar system. This proximity is the root cause of nearly every extreme feature this planet exhibits.

The star’s intense radiation bombards the planet constantly, heating it to extraordinary temperatures.

Being so close to the star means the planet experiences gravitational forces that Earth never encounters. These forces can stretch and squeeze the planet, potentially affecting its shape and internal structure.

The intense stellar wind from the star also strips away atmospheric particles, creating a dynamic and violent environment.

This tight orbit explains why the planet is classified as a “hot Jupiter.” Without such closeness, the temperatures would be much lower, and the atmospheric chemistry would be completely different. The star’s energy drives the massive wind speeds and creates the conditions necessary for silicate particles to form and circulate through the atmosphere.

Astronomers believe many hot Jupiters formed farther from their stars and then migrated inward over millions of years. Understanding how HD 189733 b ended up so close helps scientists develop theories about planetary migration and solar system evolution.

This dangerous proximity makes the planet uninhabitable but scientifically invaluable for understanding extreme planetary environments.

7. The heat is brutal – this is not a place for liquid water

Forget about swimming pools or rain puddles on HD 189733 b. The dayside atmosphere reaches temperatures around 1,093 degrees Celsius, which is hot enough to melt many metals.

At these temperatures, water cannot exist in liquid form, immediately ruling out any possibility of Earth-like life or habitable conditions.

To understand just how extreme this heat is, consider that lead melts at 327 degrees Celsius and aluminum at 660 degrees Celsius. The atmosphere of HD 189733 b easily exceeds both of these temperatures.

Any water molecules that might exist would be torn apart into hydrogen and oxygen atoms by the intense heat and radiation.

The nightside of the planet is cooler, but not by much. Heat from the dayside gets transported around the planet by those ferocious winds, preventing any truly cold regions from forming.

Even the “coolest” parts of this world would be unbearably hot by Earth standards, making the entire planet uniformly hostile to life as we know it.

These furnace-like conditions create a chemistry lab of extreme reactions. Elements and compounds that stay stable on Earth break down and recombine in strange ways.

Studying these processes helps scientists understand how matter behaves under extreme conditions and expands our knowledge of atmospheric physics beyond what we can observe in our own solar system.

8. The winds are faster than anything in our solar system

Hold onto your hat because the winds on HD 189733 b blow at speeds up to 5,400 miles per hour. That’s roughly seven times faster than the speed of sound on Earth.

To put this in perspective, the fastest winds ever recorded on Earth barely reach 250 miles per hour during the most violent tornadoes.

These supersonic winds result from the extreme temperature difference between the planet’s day and night sides. Hot air on the dayside expands and rushes toward the cooler nightside, creating a constant hurricane that circles the entire planet.

Unlike Earth’s weather systems that come and go, these winds never stop or slow down.

At such incredible speeds, even tiny particles become dangerous projectiles. The atmosphere doesn’t just move, it screams around the planet in a perpetual storm that makes Jupiter’s Great Red Spot look calm by comparison.

Nothing in our solar system comes close to matching these wind speeds, making HD 189733 b a unique laboratory for studying extreme atmospheric dynamics.

These winds play a crucial role in distributing heat around the planet and transporting chemical compounds through the atmosphere. They also contribute to the deadly glass rain phenomenon, carrying silicate particles at velocities that would shred any spacecraft attempting to enter the atmosphere.

Understanding these winds helps scientists predict weather patterns on other extreme exoplanets discovered in the future.

9. ‘Glass rain’ isn’t a poetic metaphor – it’s silicate particles

When scientists talk about glass rain on HD 189733 b, they mean it literally. The planet’s atmosphere contains silicate particles, the same basic material that makes up glass on Earth.

Under the extreme heat and pressure conditions on this world, these particles condense out of the atmosphere much like water vapor forms rain clouds on Earth.

The chemistry behind this phenomenon is fascinating. At the scorching temperatures found on HD 189733 b, silicates can exist in vapor form, floating through the upper atmosphere.

As these vapors move to slightly cooler regions or higher altitudes, they condense into tiny solid particles, creating clouds of glass dust.

These aren’t large glass shards like broken window pieces. Instead, think of microscopic particles, each one potentially sharp and dangerous when propelled by those 5,400-mile-per-hour winds.

The size and concentration of these particles can vary depending on atmospheric conditions, creating different types of “glass weather” across the planet.

This discovery challenged what scientists thought was possible in planetary atmospheres. On Earth, we have water rain, snow, and hail.

On other planets in our solar system, we’ve found methane rain and sulfuric acid clouds. But glass rain represents something entirely new, expanding our understanding of the exotic weather phenomena that can occur on worlds vastly different from our own.

10. The terrifying part: it likely falls sideways

Rain falling down is what we expect on Earth, but HD 189733 b breaks this rule in the most terrifying way imaginable. NASA scientists describe the glass rain on this planet as falling sideways, driven by those supersonic winds that circle the planet horizontally.

Imagine standing in a sandstorm, except the sand is glass and it’s moving at 5,400 miles per hour.

The sideways nature of this precipitation comes from the wind speed overwhelming gravity’s downward pull. While gravity still exists on HD 189733 b and would normally pull particles toward the planet’s core, the horizontal wind forces are so strong they dominate the motion of atmospheric particles.

The result is rain that travels parallel to the surface rather than perpendicular to it.

This creates a continuous blast of glass particles circling the planet in massive storm bands. There’s no safe place to hide from this onslaught, no calm eye of the storm where conditions improve.

The entire atmosphere acts like a giant sandblaster running at supersonic speeds, scouring everything in its path.

This sideways rain phenomenon has no equivalent in our solar system. It represents an extreme case of atmospheric dynamics where wind forces completely reshape how precipitation behaves.

For scientists, it’s a perfect example of how planets can develop weather patterns that seem impossible until we actually observe them happening on distant worlds.

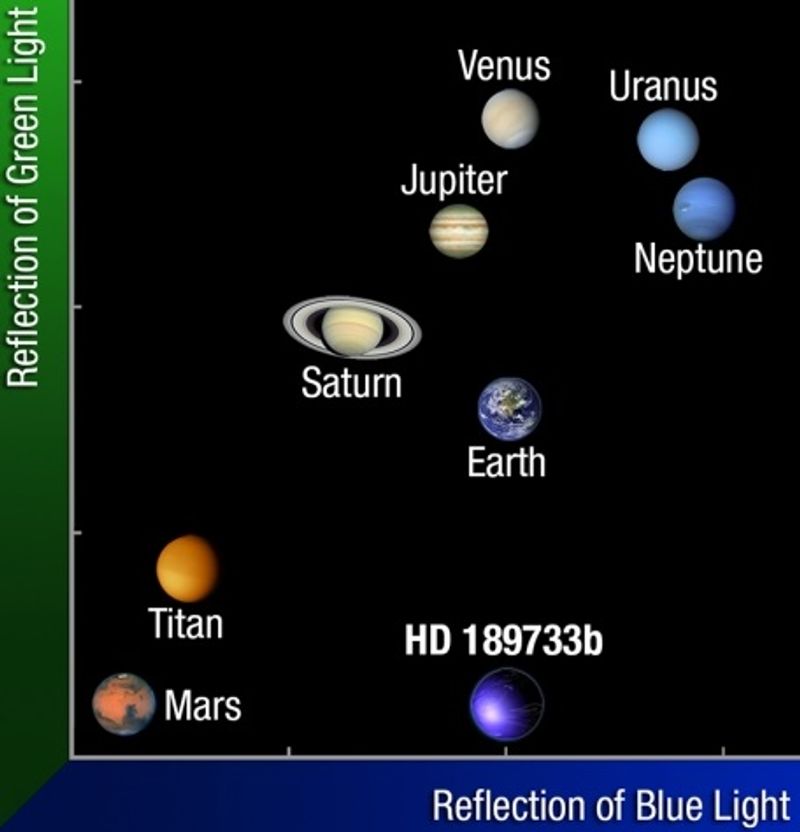

11. Why it looks blue (and why that doesn’t mean oceans)

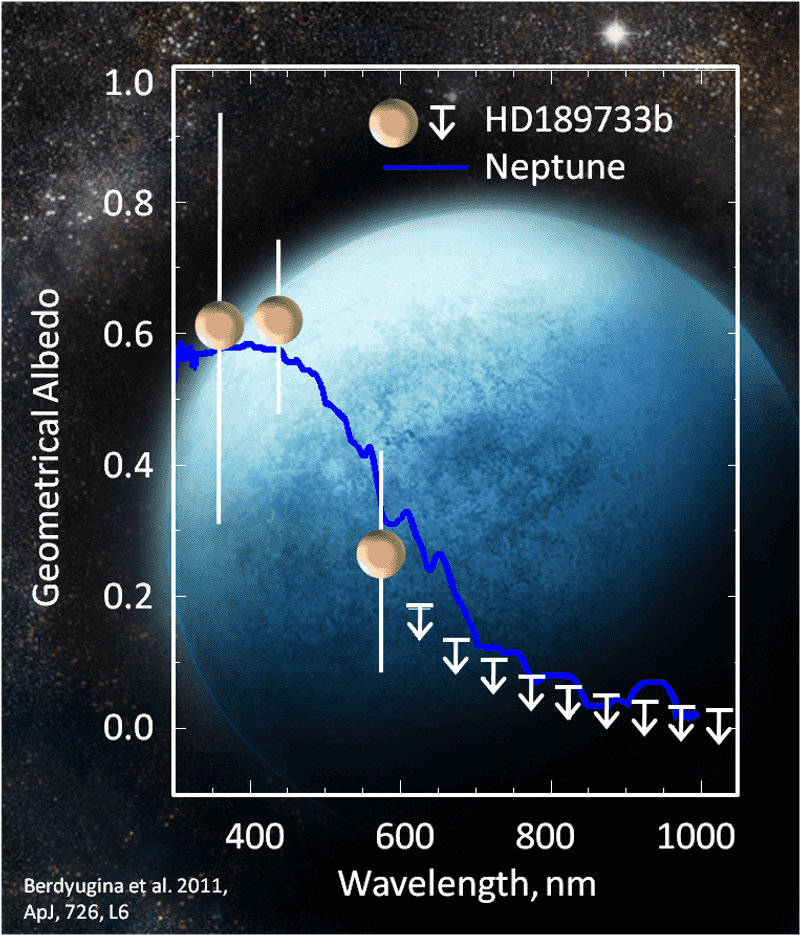

The first images of HD 189733 b shocked astronomers because the planet appeared beautifully blue, almost exactly like Earth from space. That familiar color triggered immediate comparisons to our ocean-covered home world.

However, the similarity is completely superficial and the blue color comes from an entirely different source.

NASA explains that the blue hue results from a hazy atmosphere filled with high clouds laced with silicate particles. These particles scatter light in a specific way that produces blue wavelengths, similar to how Earth’s atmosphere scatters sunlight to create our blue sky.

The scattering phenomenon is the same, but the particles doing the scattering are completely different.

On Earth, tiny nitrogen and oxygen molecules scatter blue light more than other colors, giving our sky its characteristic color. On HD 189733 b, the silicate particles in the upper atmosphere perform a similar function, but with deadly glass instead of harmless gas molecules.

The result looks peaceful from a distance but represents a violent, hostile environment up close.

This blue color serves as an important reminder that appearances can be deceiving in astronomy. Just because a planet looks Earth-like in photographs doesn’t mean it shares any other characteristics with our home.

Color alone tells us very little about habitability, composition, or safety. HD 189733 b proves that the universe can create blue planets through many different mechanisms, not all of them friendly.

12. Why scientists keep coming back to it

HD 189733 b has become a celebrity planet in the astronomy world, attracting repeated observations from telescopes around the globe and in space. Scientists return to this world again and again because it offers something rare in exoplanet research – a relatively close, bright, and well-positioned target that reveals its secrets more easily than most other distant worlds.

The planet’s proximity at just 65 light-years makes it accessible to current telescope technology. Its size and the brightness of its parent star create ideal conditions for studying its atmosphere using transit spectroscopy.

When the planet passes in front of its star, starlight filters through the atmosphere, and scientists can analyze that light to determine atmospheric composition, temperature, and weather patterns.

Beyond technical advantages, HD 189733 b represents an extreme case that helps astronomers understand the limits of planetary atmospheres. By studying how atmospheres behave under intense stellar radiation, rapid rotation, and extreme temperatures, scientists develop models that apply to other exoplanets.

It serves as a reference point for comparison when new hot Jupiters are discovered.

Each observation of HD 189733 b tests new instruments, techniques, and theories. The planet has helped validate atmospheric modeling software, train new generations of astronomers, and push the boundaries of what we can learn about distant worlds.

Its value to science extends far beyond its own characteristics to advance the entire field of exoplanet research.

13. The real takeaway: it expands our definition of ‘planet weather’

Before discovering HD 189733 b and planets like it, our understanding of weather was limited to what we observed in our own solar system. We knew about dust storms on Mars, ammonia clouds on Jupiter, and methane rain on Titan.

But glass rain driven by supersonic sideways winds represented something entirely new and unexpected.

This planet proves that nature can build weather systems far more extreme and exotic than anything we experience on Earth. It challenges meteorologists and atmospheric scientists to expand their models and theories to account for conditions that seem impossible by Earth standards.

The physics remains the same, but the outcomes can be wildly different depending on a planet’s composition, distance from its star, and other factors.

The lessons learned from HD 189733 b apply directly to future discoveries. As astronomers find more exoplanets, they can use this world as a benchmark for understanding what extreme atmospheres look like and how they behave.

It helps scientists interpret observations of newly discovered planets and make predictions about conditions on worlds we haven’t yet studied in detail.

Perhaps most importantly, HD 189733 b reminds us that Earth-sized planets might also have exotic weather we’ve never imagined. As telescope technology improves and we begin finding truly Earth-like worlds, we’ll need the knowledge gained from studying extreme cases to interpret what we observe and identify which planets might actually support life.