A hidden body of fresh water, vast enough to rival an entire region, lies buried beneath the Atlantic Ocean and holds enough water to support a megacity for centuries. Off the U.S. East Coast, scientists have confirmed the existence of a massive ancient reservoir that could reshape how we understand coastal geology and long-term water security.

This discovery traces a remarkable story through ice ages, shifting sea levels, and cutting-edge offshore drilling. Keep reading to uncover the most surprising details behind this extraordinary find – and why it could matter far beyond the ocean floor.

Turning on the tap in a city of millions and knowing the water supply is secure for generations may sound like science fiction, but that is the scale scientists are describing. Based on detailed analyses of underground volume, flow rates, and salinity gradients beneath the U.S.

East Coast, researchers estimate that this offshore freshwater reservoir could supply a city the size of New York for up to 800 years. The figure is striking, but it is grounded in careful scientific measurements rather than speculation.You might wonder whether this figure is hype or hope, and that is fair.

Researchers caution it is not a simple pipeline solution, but a capacity benchmark illustrating how large the system appears. Even with conservative assumptions, the freshwater volume rivals some of the largest onshore aquifers that support major cities today.

For you, the takeaway is perspective. Water stress is growing in many coastal regions, and knowing a vast resource may sit nearby changes the conversation.

It does not guarantee immediate access, yet it reframes long term planning, resilience, and emergency options. Think of it like a savings account you should not drain lightly, but one that can guide smarter decisions.

The water is not free floating. It is stored in tiny pore spaces within sediments and buried sand layers beneath the seafloor, separated from the ocean above by less permeable clay and silt.

Think of it as a giant natural sponge, squeezed and sealed over time, hidden from view until modern instruments and drilling revealed its reach.

This underwater storage behaves differently than a lake or cave system. Freshwater fills intergranular spaces, and its movement is governed by pressure, permeability, and the weight of overlying sediments.

Because clay layers slow down mixing, the freshwater remains relatively isolated, preserving its low salinity even under the ocean.

For coastal communities, the idea feels counterintuitive. You expect salt to dominate, yet geology writes a more complex story.

Understanding these layers helps explain why the reservoir lasts, how it recharges, and what would happen if humans ever tried to tap it. The ocean hides it, but the sedimentary architecture keeps it intact.

Evidence points to the last ice age as the reservoir’s origin, roughly 20,000 years ago. During that period, enormous ice sheets advanced over the continent, sea levels were lower, and river systems carved pathways toward a very different shoreline.

Meltwater and precipitation infiltrated exposed sediments, filling aquifers that later became submerged as seas rose again.

Scientists date the water using geochemical fingerprints and the ages of surrounding sediments. Isotopes, dissolved gases, and mineral interactions act like time markers, letting researchers estimate when the water percolated underground.

These methods do not produce a single exact birthday, but they consistently place the system’s formation in that glacial window.

For you, that age means stability and patience. The reservoir did not appear overnight, and it will not refresh instantly either.

It is an archive of climate history and coastal change, preserved far below the waves. Each sample carries a faint echo of ancient ice, winds, and shorelines that no longer exist.

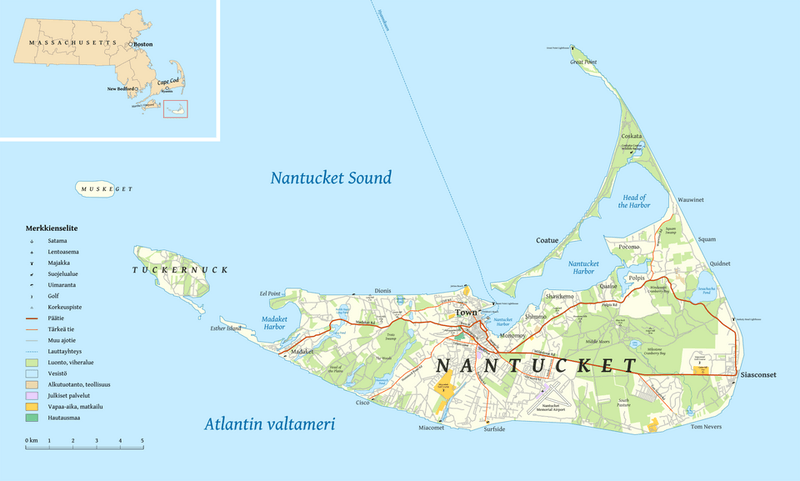

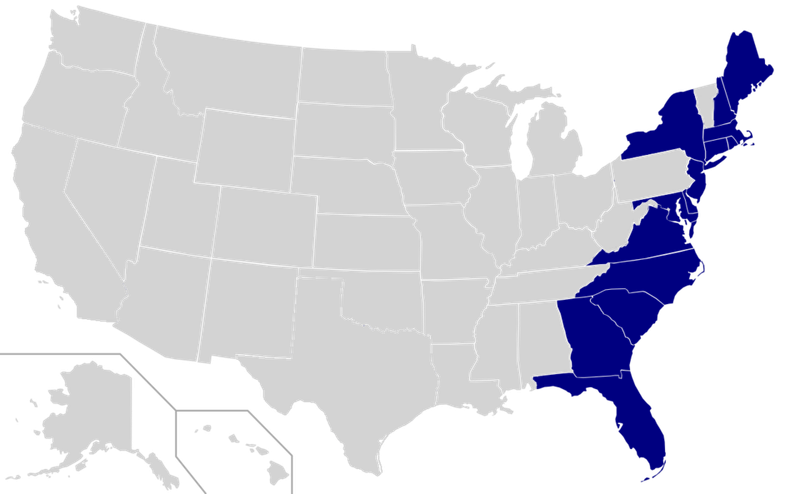

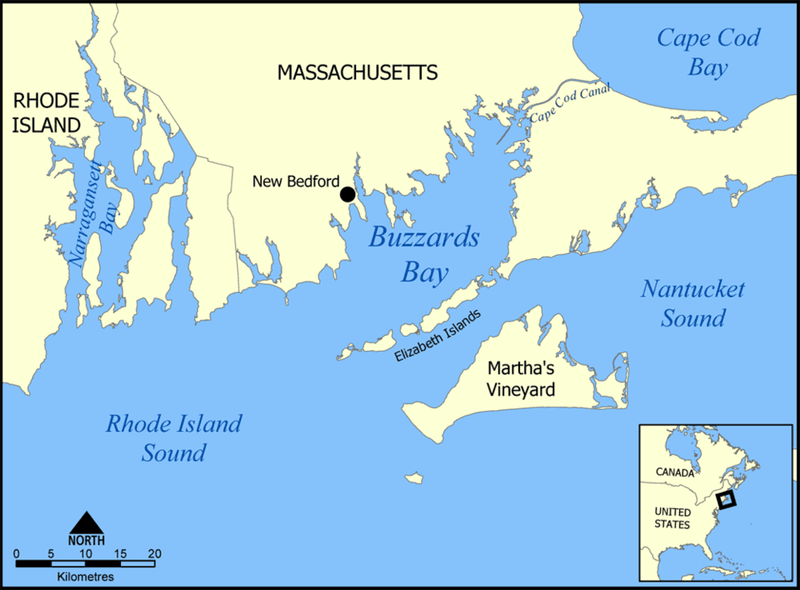

Early studies hinted at a localized feature, but mapping now shows a system extending from offshore New Jersey to Maine. That scale matters because it connects multiple sedimentary basins and ancient river valleys, suggesting a regional freshwater network rather than isolated pockets.

When you zoom out, the pattern reveals geologic continuity sculpted by ice and sea level change.

Scientists combine seismic surveys, electromagnetic sensing, borehole data, and salinity measurements to trace its boundaries. Each technique adds a layer to the picture, like stacking transparencies until an outline emerges.

While edges remain fuzzy, the overall reach points to hundreds of miles of connected or closely neighboring freshwater bodies.

For residents along the coast, this means the story is not just about one state. It is a shared resource shaped by shared history.

Long stretches of submerged plains and channels act as conduits and storage, creating a patchwork that, collectively, is enormous. The more we map, the more the system looks like a hidden blue ribbon beneath the seabed.

The idea of offshore freshwater along the East Coast is not new. USGS scientists reported evidence in the 1960s and 1970s, noting odd salinity readings and freshwater shows in offshore wells.

Over time, those hints faded from view as funding and focus shifted, leaving a promising lead in the background.

What changed was technology and curiosity. New electromagnetic methods and improved drilling tools made it possible to test the old clues at greater depth and resolution.

When the data lined up, the earlier observations finally got the attention they deserved, validating decades old field notes.

For you, it is a reminder that science is a relay. Ideas pass from one generation to another until the tools are ready to answer them well.

The rediscovery does not diminish the pioneers. It completes their unfinished sentence, turning scattered reports into a coherent, surprising narrative beneath the Atlantic.

In 2024, a team launched a three month campaign called Expedition 501 to put numbers on the legend. Ships steamed along the continental shelf, deploying drills, sensors, and sampling tools in a tight choreography.

Day and night, crews logged salinity profiles, core samples, and electromagnetic lines to sketch the aquifer’s shape.

You can picture the hustle on deck. Winches humming, cores lifted from the deep, and technicians racing to log temperatures before they shift.

Back inside, analysts cross checked readings, and maps updated in near real time, sharpening what had been a hazy outline into something measurable.

These expeditions are grueling but addictive. Weather tests patience, machinery breaks, and the ocean always gets a vote.

Yet the payoff is clarity: a clearer picture of thickness, gradients, and age that turns speculation into evidence. Expedition 501 did not finish the story, but it moved the plot forward in a big way.

To study the reservoir, researchers pumped about 13,200 gallons of water from beneath the ocean floor. That volume may sound small compared to the reservoir, but it is huge for science.

It allowed full chemical workups, isotope analyses, and microbial assessments across multiple sites and depths.

Sampling offshore is a delicate dance. Teams must avoid contamination from seawater and drilling fluids, keeping flows steady and containers sterile.

Every liter comes with a chain of custody, barcodes, temperature logs, and replicated tests to confirm what the instruments claim.

For you, the headline is reliability. Larger samples mean better statistics and stronger conclusions about origin, recharge, and potability.

The gallons pulled this season will fuel months of lab work, each test another piece in the puzzle. In research, volume unlocks nuance, and this campaign delivered enough to speak confidently about what lies below.

During the last ice age, massive ice sheets acted like hydraulic pistons. Their sheer weight pressed meltwater into permeable sands and gravels, forcing fresh water deep into the subsurface.

With sea levels lower, these sediments sat on exposed plains where infiltration could occur at large scales.

As climate warmed and oceans rose, those once open landscapes drowned. Yet the water remained in place, trapped beneath later layers of mud and silt that settled over the shelf.

You can think of the sequence as load, inject, then seal, a natural process driven by pressure and time.

This mechanism explains why the offshore aquifer is both old and extensive. It is not a small leak from land, but a legacy of glacial hydraulics.

If you picture the ice sheet as a slow moving pump, the pattern makes sense. The reservoir is a long lasting imprint of that ancient force.

Glaciers were not the only contributors. Rainfall on exposed coastal plains likely percolated into sandy layers ahead of the ice front, adding to the freshwater volume.

Rivers braided across wide floodplains, and their waters seeped downward where the sediments were porous and clean.

Geochemical fingerprints support a mixed origin. Some samples show signatures consistent with meteoric water, while others carry the hallmarks of glacial melt.

Together, they tell a story of blended sources gathered over centuries, then preserved as seas rose and sealed the system.

For planning, the blend matters. Mixed recharge histories influence mineral content, microbial communities, and how the water evolves over time.

If you are weighing sustainability, knowing the proportions helps predict quality and potential treatment needs. It is a reminder that even buried reservoirs keep memories of the skies they once captured.

A thick blanket of clay and silt acts like a lid, separating the freshwater from the salty ocean above. These fine grained layers have low permeability, so seawater struggles to move downward, and fresh water resists flushing upward.

The result is a remarkably stable boundary that preserves low salinity across long timescales.

You can compare it to a gasket in an engine. Without the seal, fluids mix and performance drops.

With it, the system holds pressure and clarity, even as waves and currents rage just meters above the seabed.

This seal is why the reservoir exists at all. Nature provided the barrier engineers would otherwise need to build.

It does not make the aquifer invincible, but it does shield it from daily ocean turbulence. That quiet protection is the unsung hero of the entire offshore freshwater story.

Closer to land, the water is nearly fresh. As you move offshore, salinity creeps upward, reflecting slower recharge and some diffusion from surrounding brines.

The gradient is expected and helpful, providing clues about flow directions and the geometry of sealing layers.

Scientists plot these gradients to target drilling and to test models. Where salinity rises faster than predicted, they search for fractures or thin seals.

Where it stays low, they infer thicker caps or higher inland inputs that counter mixing.

For potential use, the gradient sets expectations. You cannot treat every site the same, and the edge zones may need more processing before they are useful.

Think of it as a color ramp from blue to green to yellow, guiding where to study, where to protect, and where to avoid tapping prematurely.

At the closest drill site, salinity measured about 1 part per 1,000, which aligns with the upper recommended limit for drinking water. That means some pockets are almost tap ready before any treatment, a surprising result given their offshore setting.

Still, careful testing and disinfection would be essential before any public use.

You should not picture a hose running straight from the seabed to your sink. Regulations require rigorous quality checks, and chemistry can vary meter by meter underground.

But the fact that water this fresh exists so close to the coast is a remarkable confirmation of the seal’s effectiveness.

For emergency planning, such sites could act as strategic reserves. With managed withdrawals and monitoring, they could buffer droughts or disasters.

The science does not advocate immediate extraction, yet it shows that safe to drink is not a fantasy. It is already showing up in the samples.

After sampling tools are pulled, the holes do not stay open. Soft sediments slump and compact, and clay layers flow just enough to close the pathway.

This self sealing behavior reduces the risk of creating artificial conduits that could let seawater contaminate the freshwater zones.

Engineers still follow strict protocols to confirm closure. They monitor pressure, run post drill surveys, and, if needed, add benign plugs that match the surrounding material.

The goal is to leave the reservoir in the same protected state it was found.

For you, that means the science is not careless. The ocean floor can heal quickly at these scales, and crews plan for minimal footprints.

Sustainable exploration is the default, both ethically and scientifically, because nothing would be worse than learning by damaging the very system under study.

The water’s volume is only part of the mystery. Researchers are sequencing microbes, tracing rare earth elements, and imaging pore spaces to understand how the aquifer evolved.

Each data stream reveals interactions between water, minerals, and life that shape quality and stability.

Microbes can alter chemistry, influence corrosion, or even help clean contaminants. Minerals record changes in redox conditions and guide predictions about trace metals.

Meanwhile, pore structures control how fast water moves and how mixing might occur under stress.

Why should you care? These details decide whether the reservoir behaves predictably over decades, and what treatment would be needed if anyone ever taps it.

The science may sound esoteric, but it translates directly into reliability, safety, and cost. In short, the tiny things determine the big picture.

A protective clay and silt layer acts as a natural seal, preventing salty water from intruding into the freshwater below. Instruments confirm its low permeability and consistent thickness across wide areas.

Without this barrier, the aquifer would mix rapidly and lose its valuable low salinity.

Scientists validate the seal using pressure tests and tracer studies. They look for places where flow might sneak through and compare measurements against simulations.

Agreement between models and observations builds confidence that the seal performs as expected.

For you, the message is simple. The seal is the reason the reservoir remains usable in theory, even after thousands of years.

Respecting that integrity is the first rule of any future plan. If the lid stays tight, the water stays fresh.

As exciting as this reservoir is, it is not a tap to turn on tomorrow. Scientists emphasize understanding before extraction: mapping boundaries, modeling recharge, and assessing ecological impacts.

You deserve water security that lasts, not a quick fix that risks damaging a unique natural system.

Responsible use would require careful pilots, monitoring wells, and agreements among states and agencies. Legal frameworks for offshore groundwater are still emerging, and engineering solutions must preserve the seal and minimize subsidence.

Getting this wrong could harm habitats and reduce long term viability.

So for now, the mission is knowledge. Every sample and map brings the picture into focus.

When evidence shows a path that is safe, sustainable, and equitable, then planning can begin. Until then, patience protects the very resource that inspires hope.