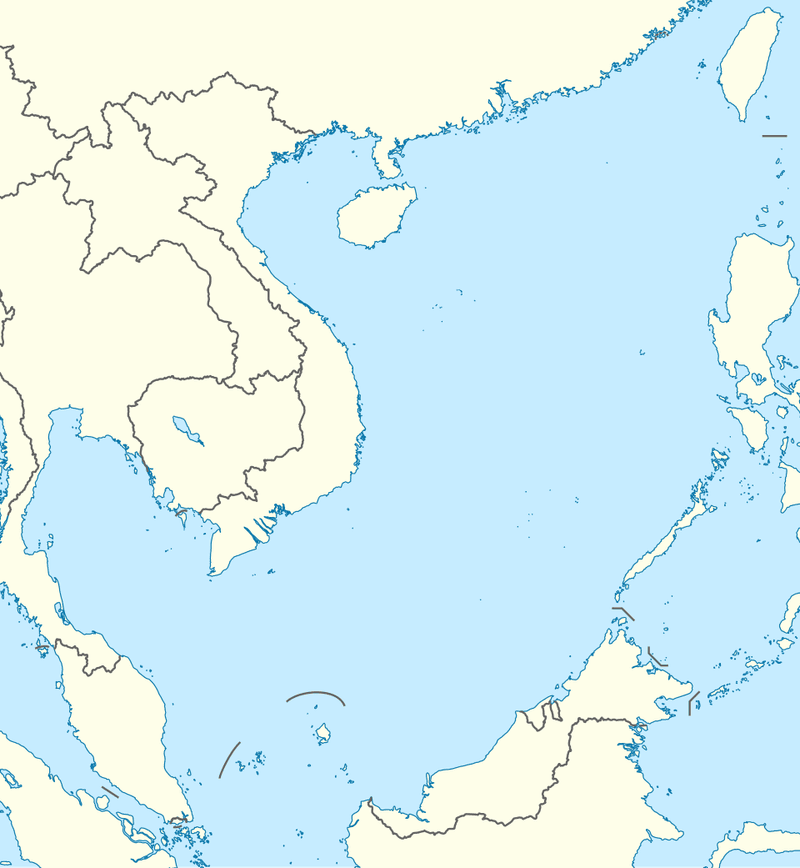

Deep beneath the ocean surface lies a mysterious underwater chasm that has captivated scientists worldwide. The Dragon Hole, located in the South China Sea, has revealed a hidden world teeming with thousands of unknown viruses and bizarre microbes that survive in total darkness.

Researchers exploring this massive pit discovered an ecosystem unlike anything seen before, where life thrives without oxygen or sunlight. This groundbreaking discovery is reshaping our understanding of how life can exist in the most extreme environments on Earth.

Imagine standing at the edge of a massive underwater canyon that plunges deeper than most skyscrapers are tall. At 301 meters deep, the Dragon Hole holds the world record for the deepest known blue hole on Earth.

This incredible depth surpasses famous blue holes like the Great Blue Hole in Belize by over 170 meters.

The vertical walls of this natural wonder drop straight down into darkness, creating an environment that remains largely unexplored. Most coral reefs only reach depths of about 30 to 50 meters, making the Dragon Hole six times deeper than typical reef ecosystems.

Sunlight cannot penetrate past 200 meters in even the clearest ocean water, meaning the bottom third of this hole exists in permanent darkness.

Scientists use specialized equipment and remotely operated vehicles to study these extreme depths. The pressure at the bottom is approximately 30 times greater than at the surface, creating conditions that crush most conventional diving equipment.

Continental shelves, the underwater edges of continents, typically extend to about 200 meters, making the Dragon Hole deeper than many of these geological features.

This extraordinary depth creates unique conditions that have allowed entirely new forms of life to evolve in isolation.

Long before humans walked the Earth, powerful natural forces were sculpting the Dragon Hole into existence. Research published in the prestigious journal Nature reveals that this massive pit formed during ancient ice ages when sea levels dropped by more than 100 meters.

During these periods, the area that is now underwater was exposed to air and rain.

Rainwater is naturally slightly acidic, and over thousands of years, it slowly dissolved the limestone bedrock beneath the surface. This process, called chemical weathering, carved steep walls and created the distinctive step-like formations visible today.

The walls show clear evidence of different water levels from various prehistoric periods.

When the last ice age ended about 10,000 years ago, melting glaciers caused sea levels to rise dramatically. The rising ocean eventually flooded the Dragon Hole, filling it with seawater and sealing its prehistoric structure beneath the waves.

This flooding created a time capsule that preserved unique geological features from a vastly different era.

The limestone formations inside the hole contain clues about ancient climate patterns and environmental conditions. Scientists study these rock layers much like reading pages in a history book, learning about Earth’s past from the physical evidence left behind.

Picture a giant bottle with a narrow neck sitting at the bottom of the ocean. That is essentially what the Dragon Hole resembles in terms of water circulation.

Unlike open ocean environments where currents constantly mix and refresh the water, this blue hole functions as an isolated chamber with minimal connection to the surrounding sea.

The narrow opening at the top and the steep vertical walls prevent normal ocean currents from penetrating deep into the hole. Surface water, which is typically warmer and oxygen-rich, cannot easily sink down into the depths.

Similarly, the dense, cold water at the bottom has no way to rise up and mix with fresher water from above.

This lack of vertical mixing is extremely rare in ocean environments. Most underwater areas experience some degree of water circulation from tides, currents, or temperature differences.

The Dragon Hole’s unique shape and structure create a barrier that keeps different water layers completely separated.

This isolation allows extreme chemical gradients to develop and remain stable for extended periods. Without mixing, each layer develops its own distinct chemistry, temperature, and biological community.

Scientists can study these stable layers to understand how isolated ecosystems function over long time periods without external influences.

Oxygen is essential for most life forms we encounter daily, but it vanishes with alarming speed inside the Dragon Hole. Researchers from the First Institute of Oceanography of China conducted extensive measurements throughout the hole’s depth and discovered a startling pattern.

Near the surface, oxygen levels are normal, similar to the surrounding ocean water that supports fish, coral, and other marine creatures.

However, as instruments descended deeper into the hole, oxygen concentrations began dropping rapidly. Within just the first 100 meters, oxygen levels plummeted dramatically.

By the time measurements reached 150 meters, barely halfway to the bottom, oxygen had completely disappeared.

This creates what scientists call anoxic conditions, meaning absolutely no oxygen is present in the water. Anoxic environments are incredibly hostile to most familiar life forms.

Fish, crustaceans, and other animals that rely on breathing dissolved oxygen cannot survive in these depths.

The rapid oxygen depletion occurs because microbes in the upper layers consume available oxygen faster than it can be replenished. Without water circulation to bring fresh oxygen down from the surface, the deeper zones remain permanently oxygen-free.

This extreme environment forces any surviving organisms to develop completely different strategies for generating energy and staying alive.

Rather than being one uniform environment, the Dragon Hole contains multiple distinct zones stacked on top of each other like layers in a cake. Each layer has its own unique chemical signature, temperature profile, and biological inhabitants.

These stratified zones remain separate from one another due to differences in water density and the lack of mixing currents.

Scientists identified at least three major zones during their exploration. The uppermost zone contains oxygen and supports organisms similar to those found in normal ocean environments.

Below this, the first anoxic zone begins, where oxygen disappears but other chemicals like nitrates become important.

Even deeper, a second anoxic zone exists with completely different chemistry. Here, hydrogen sulfide accumulates to high concentrations, creating a toxic environment that would be deadly to surface-dwelling creatures.

The chemical differences between these zones can be as dramatic as the difference between freshwater and saltwater.

These stable chemical layers allow radically different ecosystems to exist just meters apart vertically. Microbes living in one zone would likely die if transported to another zone, even though they are physically very close.

This creates multiple isolated habitats within a single geological structure, each supporting its own unique community of specialized organisms adapted to those specific conditions.

Cross the 100-meter threshold in the Dragon Hole, and you enter a realm where familiar marine life ceases to exist. Fish that swim freely in the upper portions of the hole cannot venture into these deeper waters.

The combination of zero oxygen, increasing pressure, and complete darkness creates an impenetrable barrier for traditional ocean animals.

Algae and other photosynthetic organisms also disappear entirely at this depth. Plants and algae require sunlight to produce energy through photosynthesis, and sunlight cannot penetrate to these depths even in the clearest ocean water.

Without light, photosynthetic life simply cannot survive.

Coral, sponges, and other stationary marine animals that typically colonize underwater walls are also absent. These creatures rely on oxygen dissolved in the water and food particles carried by currents.

The anoxic, stagnant conditions below 100 meters provide neither of these essential requirements.

From this point downward, the ecosystem belongs exclusively to microbes. Bacteria and archaea, microscopic single-celled organisms, are the only life forms capable of surviving in such extreme conditions.

These microbes have evolved specialized metabolic pathways that allow them to generate energy without oxygen or sunlight, using chemical reactions instead. This transition marks a fundamental shift from the familiar world of animals and plants to an alien microbial realm.

In the pitch-black depths of the Dragon Hole, life persists through an entirely different energy strategy than the one used by plants and animals at the surface. Organisms here rely on chemosynthesis rather than photosynthesis to survive.

While photosynthesis uses sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into sugars, chemosynthesis uses chemical reactions to generate energy.

Microbes in these dark zones harness energy from chemical compounds dissolved in the water. Sulfur compounds, nitrogen-based molecules, and hydrogen gas serve as fuel sources.

When these chemicals react with each other, they release energy that bacteria can capture and use to power their cellular processes.

This type of ecosystem closely resembles those found near deep-sea hydrothermal vents. At these underwater volcanic sites, superheated water rich in chemicals erupts from the seafloor.

Bacteria colonize these vents and form the base of a food chain that supports tube worms, crabs, and other specialized creatures, all without any sunlight.

The Dragon Hole demonstrates that chemosynthesis-based ecosystems can exist in places other than hydrothermal vents. This discovery expands our understanding of where life can thrive on Earth.

It also has implications for the search for life on other planets and moons, where sunlight may be scarce but chemical energy sources might exist.

Scientists identified the first major deep layer as Anoxic Zone I, and it has a clear microbial ruler. Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria make up nearly 90 percent of all microbial life in this zone, creating one of the most specialized ecosystems ever discovered.

These bacteria have evolved to thrive in conditions that would kill most other organisms.

Two genera dominate this zone almost completely. Thiomicrorhabdus and Sulfurimonas are the primary inhabitants, and both specialize in oxidizing sulfur compounds to generate energy.

These bacteria take reduced sulfur molecules and convert them to more oxidized forms, capturing energy in the process.

The overwhelming dominance of just two bacterial types is unusual even for extreme environments. Typically, ecosystems contain a diverse mix of organisms filling different ecological roles.

The fact that Anoxic Zone I is so heavily dominated by sulfur-oxidizers suggests that the environmental conditions strongly favor this particular metabolic strategy.

These bacteria play a critical role in sulfur cycling within the Dragon Hole. They prevent toxic hydrogen sulfide from accumulating to even higher concentrations by converting it to less harmful sulfur compounds.

Without these microbial workers, the chemistry of the entire hole would be dramatically different. Their metabolic activity shapes the environment and makes it possible for other organisms to survive in deeper zones.

Below 140 meters, explorers enter a completely different world called Anoxic Zone II. The environmental conditions shift so dramatically at this boundary that it might as well be a different planet.

Chemical measurements show that substances abundant in the upper zones disappear entirely, while new compounds accumulate to high concentrations.

Nitrates, which are important nitrogen compounds used by many bacteria in Anoxic Zone I, vanish completely in this deeper zone. Without nitrates available, microbes cannot use certain metabolic pathways that depend on these molecules.

This forces bacteria to switch to entirely different strategies for generating energy and processing nutrients.

Hydrogen sulfide, a toxic gas that smells like rotten eggs, accumulates to much higher levels in Anoxic Zone II. This compound is produced by bacteria breaking down sulfate molecules and is poisonous to most life forms.

Only highly specialized microbes can tolerate such extreme sulfide concentrations.

The transition between zones is sharp rather than gradual. Within just a few meters of depth, the chemical environment transforms completely.

This creates a clear boundary where organisms adapted to one zone cannot survive in the other. Microbes living in Anoxic Zone II must possess unique genetic adaptations that allow them to function in this harsh chemical environment.

In the deepest, darkest regions of the Dragon Hole, a different group of bacteria claims dominance. Sulfate-reducing bacteria become the primary inhabitants in Anoxic Zone II, replacing the sulfur-oxidizing bacteria that ruled the shallower depths.

These microbes perform the opposite chemical process, reducing oxidized sulfur compounds back to their reduced forms.

Three bacterial genera are particularly abundant in these extreme depths. Desulfatiglans, Desulfobacter, and Desulfovibrio all specialize in sulfate reduction, a metabolic process critical to sulfur cycling in oxygen-free environments.

These bacteria take sulfate molecules dissolved in the water and strip away oxygen atoms, releasing energy in the process.

Sulfate reduction produces hydrogen sulfide as a waste product, which explains why this toxic compound accumulates to high concentrations in the deepest zones. While hydrogen sulfide is poisonous to most organisms, these specialized bacteria have evolved mechanisms to tolerate and even thrive in its presence.

They possess unique enzymes and cellular structures that prevent the sulfide from damaging their cells.

The presence of sulfate-reducing bacteria in such high numbers indicates that sulfate is abundant in the deep waters. This creates a stable energy source that supports a substantial microbial population.

These bacteria form the foundation of the deep ecosystem, processing chemicals and making energy available to other microbes and viruses.

One of the most puzzling discoveries in the Dragon Hole was the presence of green sulfur bacteria in the deepest, darkest layers. Bacteria like Prosthecochloris typically use photosynthesis to generate energy, but they were found thriving in zones where absolutely no light penetrates.

This finding initially confused researchers who expected photosynthetic organisms to be limited to sunlit waters.

Green sulfur bacteria are remarkable for their ability to photosynthesize using extremely low light levels. They can capture and use wavelengths of light that other photosynthetic organisms cannot detect.

Some species can function with light levels thousands of times dimmer than what plants need to survive.

However, in the depths of the Dragon Hole, even these sensitive bacteria cannot access sunlight. Scientists believe these microbes have switched to alternative metabolic strategies that do not require light.

They may be using chemical energy sources instead, demonstrating extraordinary metabolic flexibility.

This discovery highlights how adaptable bacteria can be when faced with extreme environmental challenges. Rather than dying when their preferred energy source disappears, some bacteria can activate backup metabolic pathways coded in their genes.

This evolutionary flexibility allows them to colonize environments that would otherwise be completely uninhabitable. The presence of these bacteria in total darkness suggests they may play unexpected roles in deep-zone ecosystems.

Beyond the dominant bacterial groups, researchers discovered numerous rare and poorly understood microbes living throughout the Dragon Hole. Organisms from obscure groups such as Chloroflexi and Parcubacteria appeared in samples, many of which have been detected in only a handful of environments worldwide.

These mysterious microbes remain largely unstudied because they are difficult to find and even harder to grow in laboratory settings.

Chloroflexi, sometimes called green non-sulfur bacteria, are a diverse group with members living in hot springs, soil, and ocean sediments. Their metabolic capabilities vary widely, with some performing photosynthesis while others rely on chemical energy.

The Chloroflexi found in the Dragon Hole likely use chemosynthesis, though their exact role in the ecosystem remains unclear.

Parcubacteria are even more enigmatic. These tiny bacteria have unusually small genomes and seem to lack genes for certain essential cellular functions.

Scientists suspect they may be symbionts or parasites that depend on other bacteria for survival. Their presence in the Dragon Hole suggests complex interactions between different microbial species.

The discovery of these rare groups indicates that the Dragon Hole may host metabolic pathways and biochemical processes never observed elsewhere. Each unusual microbe potentially represents a unique evolutionary solution to surviving in extreme conditions.

Studying these organisms could reveal new enzymes, chemical reactions, and biological strategies with applications in medicine, industry, and biotechnology.

Collecting samples from the Dragon Hole was only the first step in understanding its microbial ecosystem. Researchers faced the challenging task of growing bacteria from these extreme environments in laboratory settings.

Successfully cultivating microbes from anoxic, high-pressure, dark environments requires specialized equipment and techniques that mimic the conditions found in their natural habitat.

Through careful work, scientists managed to grow 294 distinct bacterial strains under controlled laboratory conditions. This represents a significant achievement, as many extremophile bacteria refuse to grow outside their native environments.

Each successfully cultivated strain provides a living library of genetic and metabolic information that researchers can study in detail.

Growing bacteria in the lab allows scientists to conduct experiments that would be impossible in the field. They can test how bacteria respond to different chemicals, temperatures, and nutrient levels.

They can sequence bacterial genomes to identify genes responsible for survival in extreme conditions.

These cultivated strains also serve as reference organisms for future research. Other scientists can request samples to conduct their own studies, building a growing body of knowledge about Dragon Hole microbes.

Some of these bacteria may produce useful enzymes or compounds that could have industrial or medical applications. The 294 strains represent a treasure trove of biological diversity waiting to be fully explored and understood.

Among the 294 bacterial strains cultivated from the Dragon Hole, researchers made an astonishing discovery. More than 22 percent of the anaerobic bacteria identified had never been documented in any previous scientific study.

These completely novel organisms represent new branches on the tree of life, expanding our understanding of bacterial diversity.

Discovering new bacterial species is not uncommon, as microbes are incredibly diverse and many environments remain unexplored. However, finding that over one-fifth of cultivated strains are entirely new is exceptional.

This high proportion of novel bacteria indicates that the Dragon Hole harbors a unique ecosystem that evolved in isolation from other marine environments.

Each new bacterial species must be carefully characterized and described before it can be officially recognized by the scientific community. Researchers analyze the bacteria’s physical appearance, genetic sequence, metabolic capabilities, and evolutionary relationships to other known organisms.

This process can take months or years for each new species.

These discoveries make the Dragon Hole a major hotspot for biological exploration. The new bacteria may possess unique adaptations that could inspire biotechnology applications, such as enzymes that function in extreme conditions or novel pathways for producing useful chemicals.

Understanding these organisms also helps scientists develop better models of how life adapts to extreme environments, with implications for astrobiology and the search for life beyond Earth.

The most startling discovery from the Dragon Hole exploration was the identification of 1,730 different virus types living throughout the water column. This massive viral diversity rivals some of the most virus-rich environments ever studied.

Most of these viruses are bacteriophages, which specifically infect bacteria rather than animals or plants.

Bacteriophages play a crucial role in controlling microbial populations. Each phage typically infects only specific bacterial species, injecting its genetic material into the cell and hijacking the bacteria’s machinery to produce more viruses.

When the infected cell bursts, it releases dozens of new phages to infect neighboring bacteria.

This viral predation prevents any single bacterial species from completely dominating the ecosystem. Phages act as population control agents, killing bacteria when they become too abundant.

This creates space and resources for other bacterial species to thrive, maintaining diversity within the microbial community.

In the deepest layers of the Dragon Hole, many viruses could not be classified into any known viral families. These mysterious phages may represent entirely new viral lineages that evolved alongside their bacterial hosts in this isolated environment.

Some may use unusual genetic codes or infection strategies never observed before. Understanding these viruses could reveal fundamental insights into viral evolution and the intricate relationships between viruses and bacteria in extreme ecosystems.