The Sauk people played a crucial role in shaping the early United States, yet their story often gets overlooked in history books. From their strategic control of major trade routes to their resistance against forced removal, the Sauk influenced American expansion in ways that still matter today.

Their experiences with treaties, warfare, and displacement reveal the complicated truth behind westward growth. Understanding the Sauk means understanding a vital piece of American history that connects past injustices to present-day Native communities.

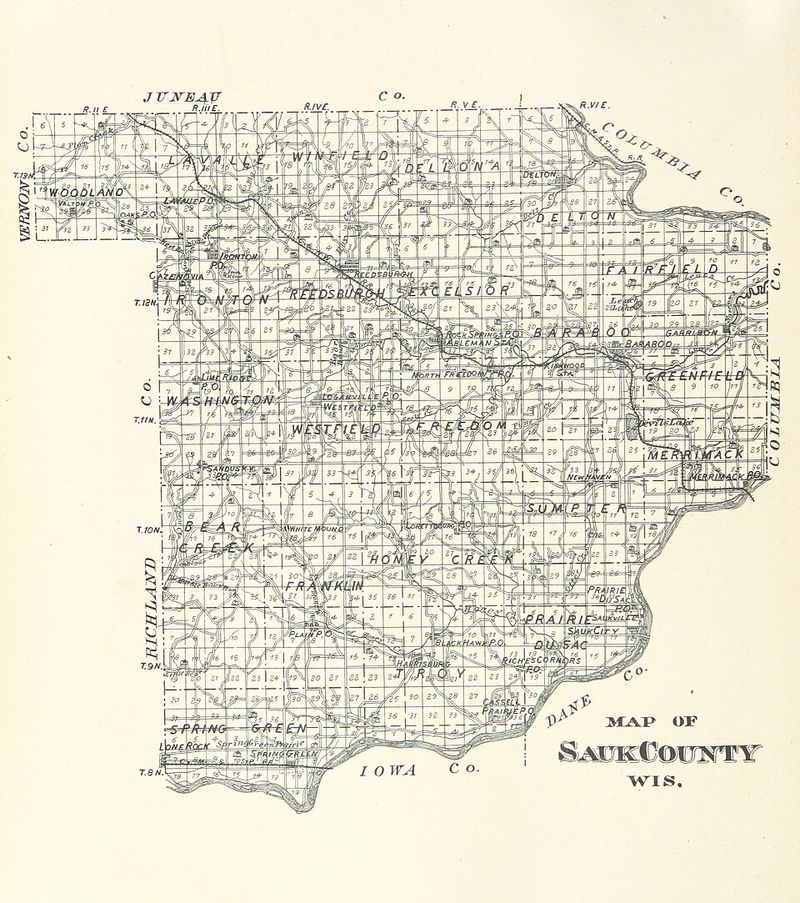

The Sauk Were Originally a Great Lakes Tribe

Long before European settlers arrived, the Sauk established thriving communities around the Great Lakes region. Their villages dotted the shores of what we now call Michigan and Wisconsin, where abundant fish, game, and fertile soil supported their way of life.

Waterways became the lifeblood of Sauk culture and economy. Rivers and lakes provided transportation routes, fishing grounds, and trading opportunities that would later connect them to European fur traders.

These strategic locations gave the Sauk significant influence over regional trade networks.

When French explorers arrived in the 1600s, they found the Sauk already controlling key water routes. This geographic advantage transformed the tribe into essential partners for European commerce.

Their homeland’s natural resources and strategic position made them central figures in the colonial economy, setting the stage for their later involvement in shaping American territorial expansion and conflict.

Their Name Comes From People of the Yellow Earth

Words carry meaning, and the Sauk name tells us something important about their connection to the land. Oθaakiiwaki translates roughly to people of the yellow earth, referring to the distinctive clay found in their ancestral territory.

This wasn’t just a random label but a deep connection to the physical landscape they called home.

The yellow clay held practical and spiritual significance. Sauk artisans shaped this earth into pottery for cooking, storage, and ceremonies.

The clay’s unique color and quality made Sauk pottery recognizable across trade networks, essentially becoming a signature of their craftsmanship.

Place names and tribal identities often reflect what matters most to a people. For the Sauk, the earth itself defined who they were.

This connection to specific land made later forced removals even more devastating, as they weren’t just losing territory but the very soil that gave them their identity and name.

They Were Closely Allied With the Meskwaki

Strength in numbers shaped survival strategies across Native America. The Sauk formed one of history’s most enduring tribal partnerships with the Meskwaki, commonly known as the Fox tribe.

This alliance went far beyond simple cooperation, creating a political and social union that lasted for centuries.

Shared villages became the norm as the two tribes intermarried and coordinated their military defenses. When one faced threats, both responded together.

Their combined forces made them formidable opponents against rival tribes and later against European encroachment. European colonists often couldn’t distinguish between the two groups, referring to them collectively as the Sac and Fox.

This partnership proved so strong that it survived forced relocations and federal policies designed to separate tribes. Today, many descendants belong to combined Sac and Fox nations.

The alliance demonstrates how Native peoples created complex diplomatic relationships that rivaled any European alliance system of the same era.

They Became Powerful Players in the Fur Trade

Economic power shifted dramatically when European demand for beaver pelts exploded in the 1600s and 1700s. The Sauk recognized this opportunity and positioned themselves as essential middlemen in the French fur trade.

Their knowledge of interior regions and existing trade networks made them invaluable partners for French merchants seeking quality furs.

Sauk hunters became expert trappers, but their real genius lay in organizing larger trade operations. They collected furs from smaller tribes, negotiated prices, and transported goods across vast distances.

This role generated wealth and political influence that extended far beyond their immediate territory.

The fur trade transformed Sauk society in complex ways. Metal tools, guns, and European goods improved daily life but also created dependency on trade relationships.

When the fur trade declined and political power shifted to the British and Americans, the Sauk found themselves vulnerable in ways their ancestors never experienced.

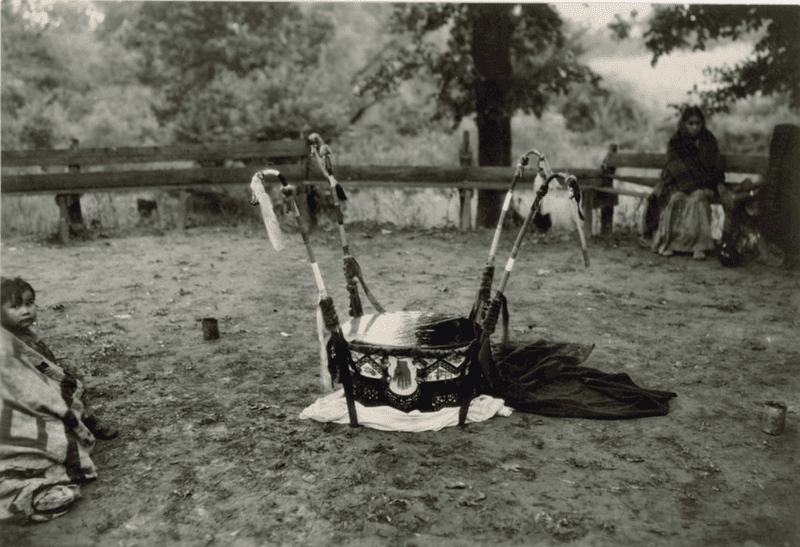

Sauk Society Was Clan-Based and Matrilineal

Family structures reveal a lot about cultural values. Unlike European societies where fathers determined family identity and inheritance, the Sauk traced lineage through mothers.

Children belonged to their mother’s clan, and clan membership determined everything from marriage possibilities to leadership eligibility.

Multiple clans existed within Sauk society, each with specific responsibilities and ceremonial roles. You couldn’t marry someone from your own clan, ensuring genetic diversity and creating bonds between different clan groups.

These rules maintained social harmony and distributed power across the community rather than concentrating it in individual families.

Women held considerable authority in this system, controlling property and having significant voices in community decisions. When European colonists arrived with patriarchal assumptions, they often misunderstood Sauk political structures.

Treaty negotiations sometimes failed because Europeans only spoke with men, not recognizing that women’s councils held substantial decision-making power in Sauk governance.

They Practiced Seasonal Migration

Staying in one place year-round wasn’t practical or efficient for Sauk communities. Instead, they developed a sophisticated seasonal cycle that maximized the Midwest’s natural resources.

Summer meant permanent villages where women cultivated corn, beans, and squash in fields near rivers. These Three Sisters crops provided reliable nutrition and could be stored for months.

When autumn arrived and crops were harvested, families packed up for winter hunting expeditions. Small groups traveled to traditional hunting grounds where men tracked deer, elk, and other game.

This mobility allowed the land near permanent villages to rest and regenerate while providing fresh meat and valuable furs during cold months.

This pattern wasn’t random wandering but a carefully planned system passed down through generations. Everyone knew when to plant, when to harvest, and when to hunt.

The seasonal migration demonstrated sophisticated environmental management that sustained Sauk communities for centuries before European contact disrupted these ancient patterns.

Their Villages Were Strategically Located

Geography determines destiny in ways we often overlook. The Sauk didn’t randomly choose village locations but selected sites with careful strategic consideration.

Major rivers like the Mississippi, Rock, and Illinois became home to Sauk settlements, giving them control over the region’s most important transportation corridors.

Controlling river access meant controlling commerce and communication. Anyone traveling through the region needed to pass through or near Sauk territory.

This positioning allowed them to monitor potential threats, collect intelligence about rival groups, and dominate trade relationships. Their villages essentially functioned as checkpoints on the Midwest’s highway system.

When Americans began pushing westward in the early 1800s, they quickly recognized what the Sauk already knew. These river locations were perfect for future American towns and cities.

This strategic value made Sauk lands highly desirable to settlers and the U.S. government, directly contributing to the conflicts that would eventually force the tribe from their homeland.

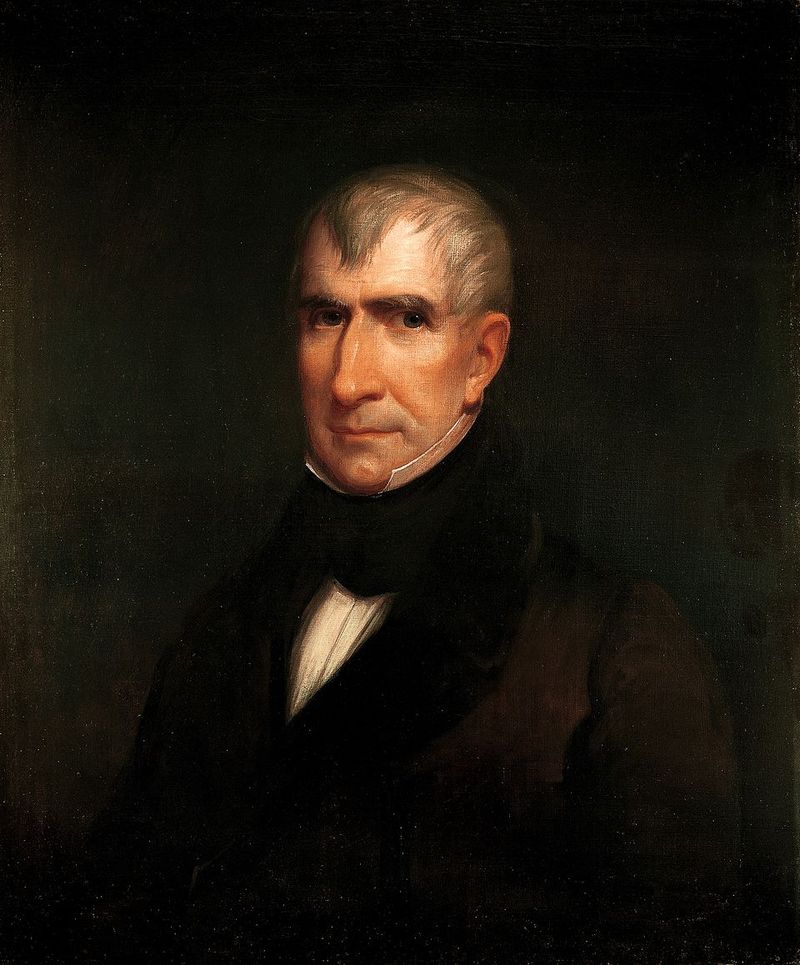

The 1804 Treaty Was Signed Without Full Consent

Some moments change everything, and the Treaty of 1804 was one of those moments for the Sauk people. In St. Louis, a small group of Sauk representatives met with William Henry Harrison, who represented the U.S. government.

What happened next would haunt the tribe for decades.

These representatives, possibly intoxicated and definitely without authority to make major decisions, signed away millions of acres of Sauk land east of the Mississippi River. The treaty wasn’t approved by tribal councils or recognized leaders.

Most Sauk people didn’t even know about it until years later. According to Sauk law and custom, the treaty was completely invalid.

The U.S. government saw things differently. They considered the treaty binding and used it to justify taking Sauk lands in Illinois and Wisconsin.

This fraudulent agreement became the legal foundation for American claims to Sauk territory, eventually leading to the Black Hawk War and forced removal westward. One illegitimate document reshaped an entire people’s future.

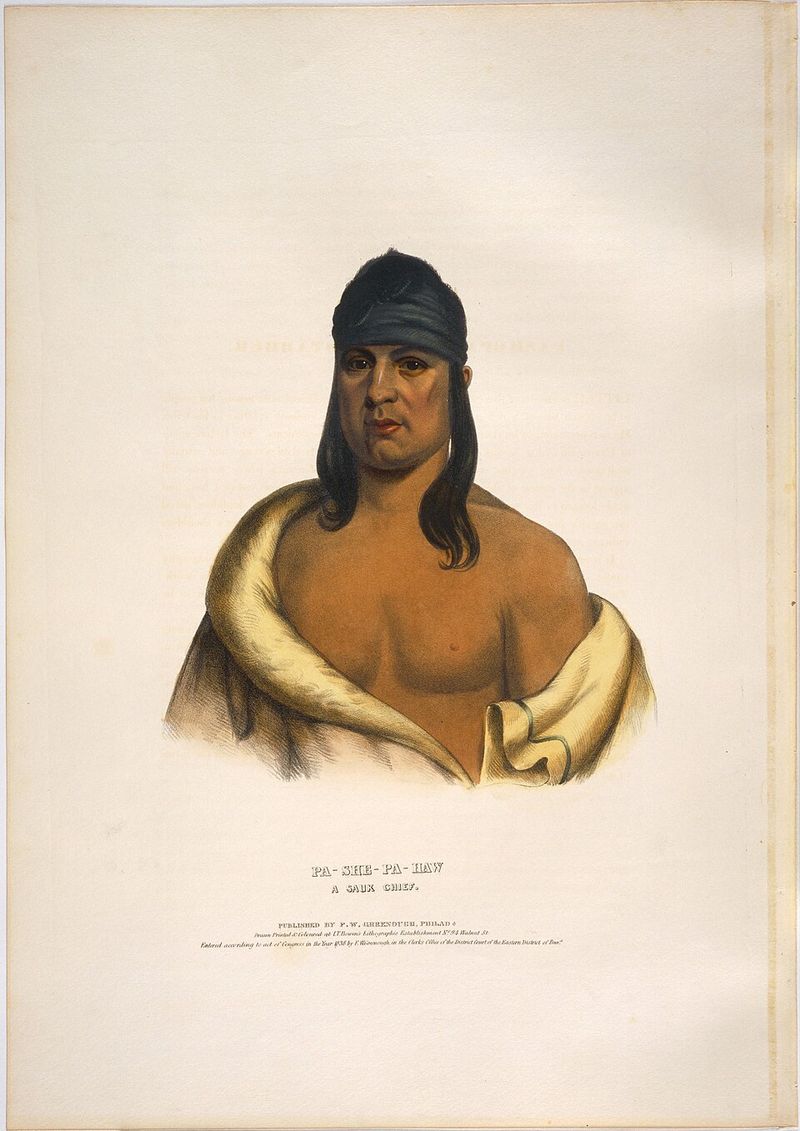

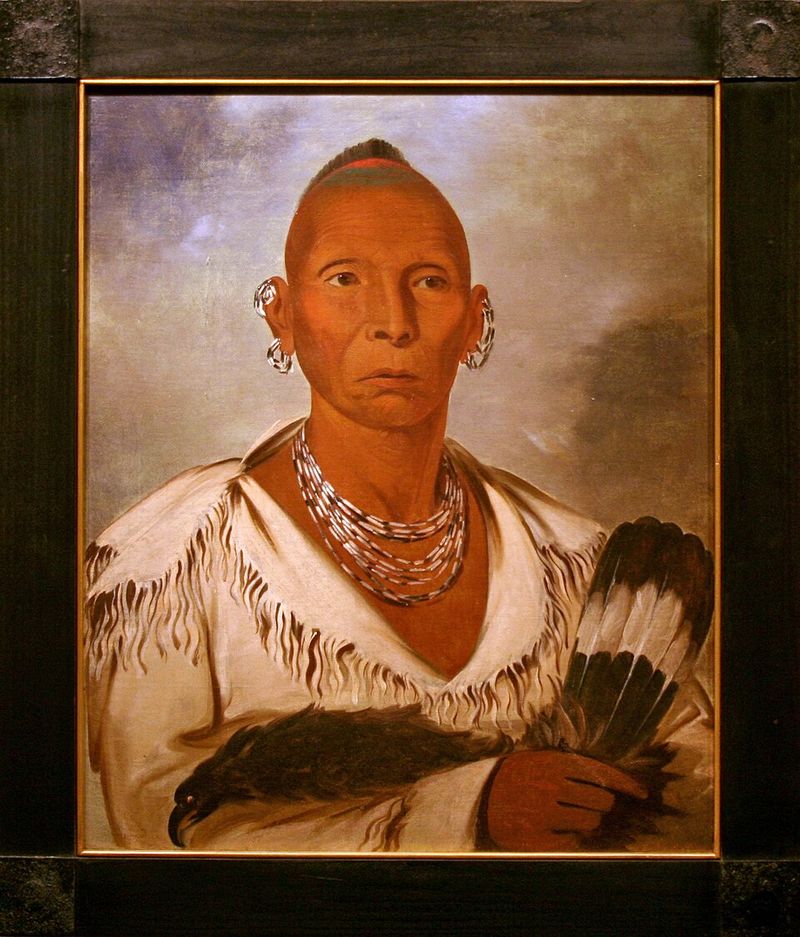

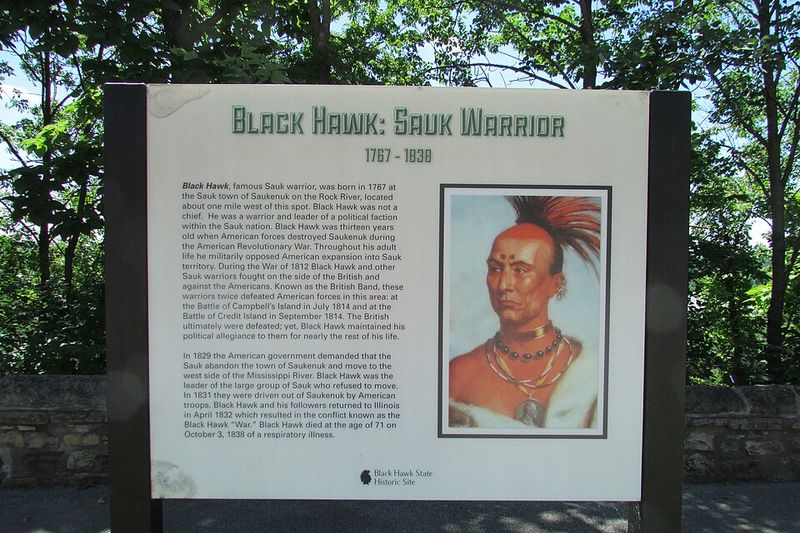

Black Hawk Became a Symbol of Native Resistance

Every movement needs a face, and Black Hawk became that face for Native resistance in the early 19th century. Born around 1767, he grew up during a time when European influence was transforming Native life.

By his sixties, he had watched his people lose land, dignity, and autonomy to American expansion.

Black Hawk refused to accept the 1804 treaty his people never properly authorized. While other Sauk leaders reluctantly moved west across the Mississippi, Black Hawk insisted on returning to Saukenuk, the tribe’s principal village in Illinois.

His stance wasn’t about starting a war but about defending what he believed were legitimate Sauk rights to their homeland.

His resistance made him famous, but also controversial. Some Sauk leaders thought his approach was reckless and would bring disaster.

They were partially right, as his 1832 attempt to reclaim Sauk lands led to war. Yet Black Hawk’s principled stand inspired other Native leaders and forced Americans to confront the moral costs of westward expansion.

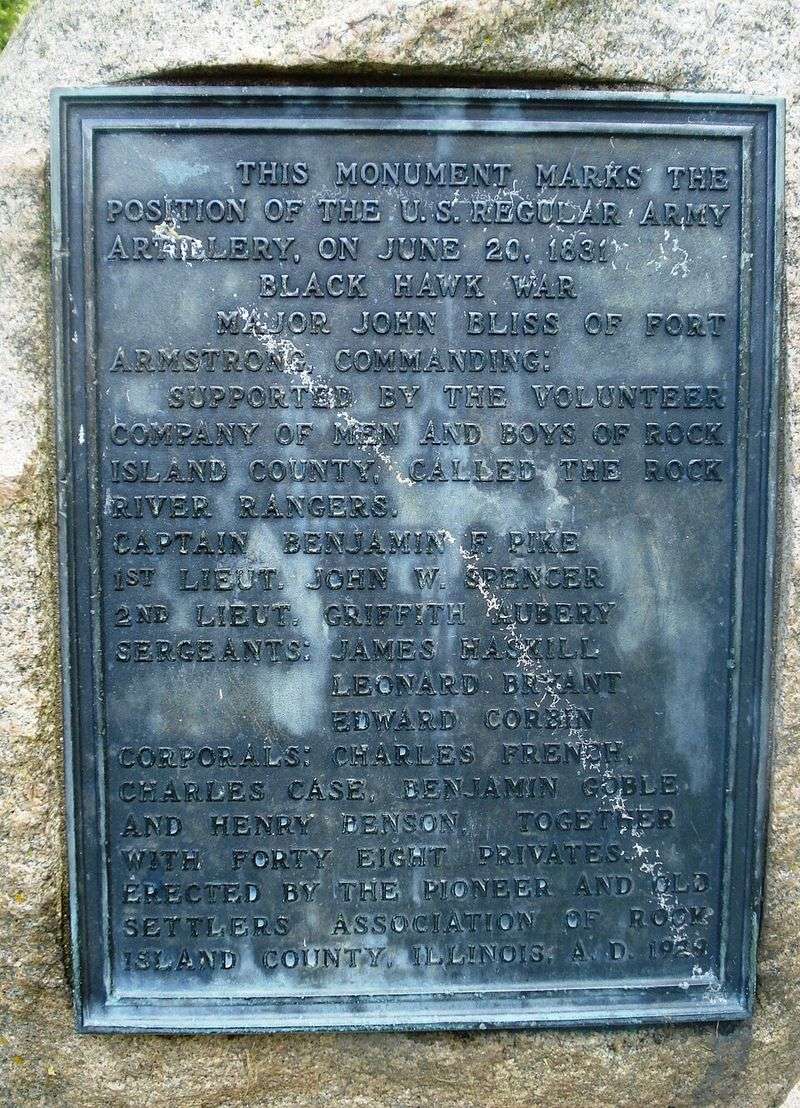

The Black Hawk War Changed U.S. Indian Policy

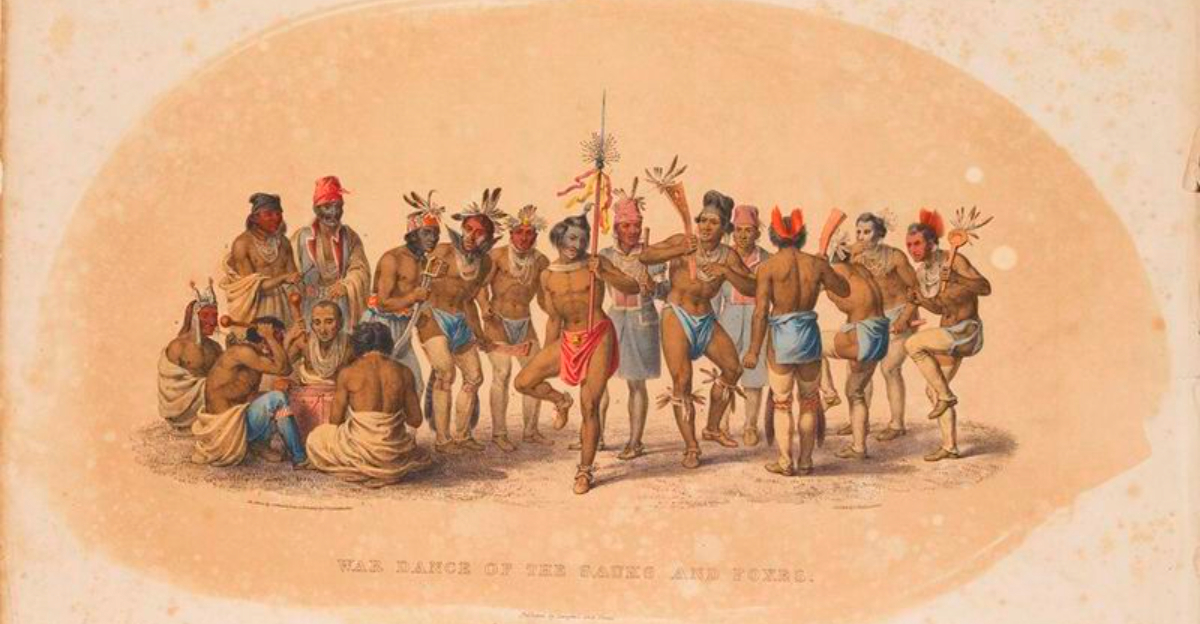

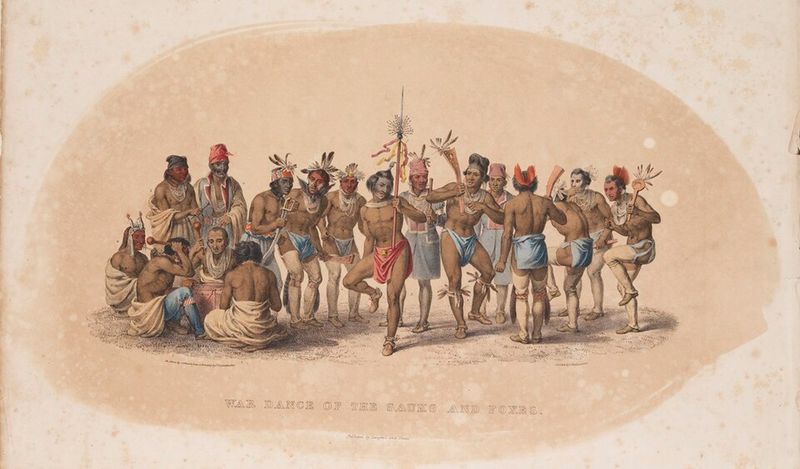

Fifteen weeks in 1832 changed federal Indian policy forever. The Black Hawk War started when Black Hawk led roughly 1,500 Sauk, Meskwaki, and Kickapoo people back across the Mississippi River into Illinois, hoping to resettle their traditional lands and possibly form alliances with other tribes.

The conflict was brief and brutal. American militia and army regulars pursued Black Hawk’s band throughout Illinois and into Wisconsin Territory.

Most of Black Hawk’s followers weren’t warriors but families seeking to return home. The war ended with the Bad Axe Massacre, where soldiers slaughtered men, women, and children trying to cross back over the Mississippi to safety.

The war’s outcome sent a clear message across Indian Country. Federal authorities would use overwhelming force to prevent tribes from returning to ceded lands, no matter how questionable the original treaties.

The conflict accelerated removal policies throughout the Midwest and established precedents that would be used against other tribes for decades. One elderly leader’s resistance campaign reshaped how America dealt with Native peoples.

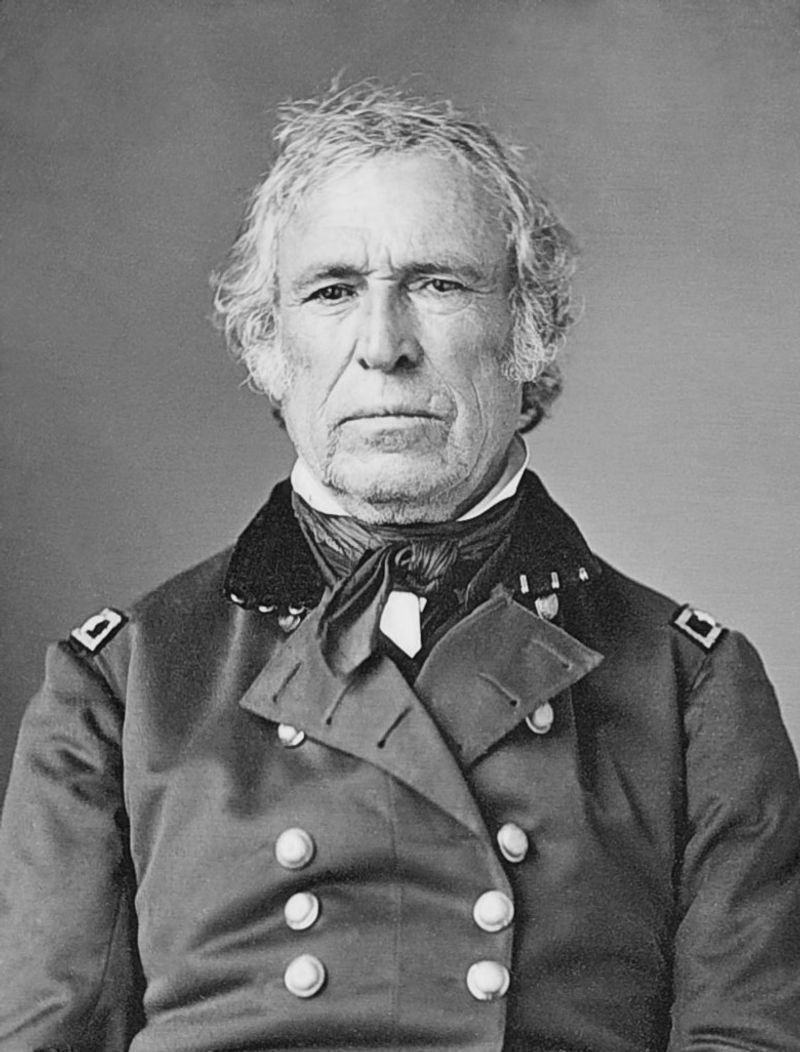

Several Future U.S. Leaders Fought Against the Sauk

History connects in unexpected ways. The Black Hawk War might seem like a minor frontier conflict, but it served as a training ground for men who would later shape the nation.

Young Abraham Lincoln enlisted in an Illinois militia company formed to fight Black Hawk’s band. Though Lincoln saw no combat, the experience introduced him to military life and frontier politics.

Jefferson Davis, who would become president of the Confederacy, served as a regular army lieutenant during the war. He actually helped guard Black Hawk after his capture.

Zachary Taylor, future U.S. president, commanded forces that pursued the Sauk. These men’s early careers intersected directly with Native American displacement.

This overlap wasn’t coincidental but revealed how westward expansion and Indian removal were central to American political life. Young ambitious men gained military credentials and political connections by participating in campaigns against Native peoples.

The Black Hawk War thus directly linked Sauk history to the broader story of American political development and the leaders who would guide the nation through its greatest crises.

Black Hawk’s Imprisonment Shocked the Nation

After his defeat and capture, Black Hawk expected execution. Instead, the government decided to make an example of him in a different way.

In 1833, authorities took the elderly war leader on a tour of major Eastern cities including Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. The goal was to demonstrate American power and convince other Native leaders that resistance was futile.

The tour backfired in unexpected ways. Thousands of Americans turned out to see Black Hawk, but many felt sympathy rather than triumph.

They saw a dignified old man who had fought for his homeland, not a savage villain. Newspapers published his speeches and story, exposing Eastern audiences to the human cost of westward expansion for the first time.

Black Hawk became a celebrity, his autobiography became a bestseller, and his portrait was painted by respected artists. This public attention sparked debates about Indian policy and American treatment of Native peoples.

The government wanted to use Black Hawk as propaganda, but instead created a symbol that questioned the morality of removal policies.

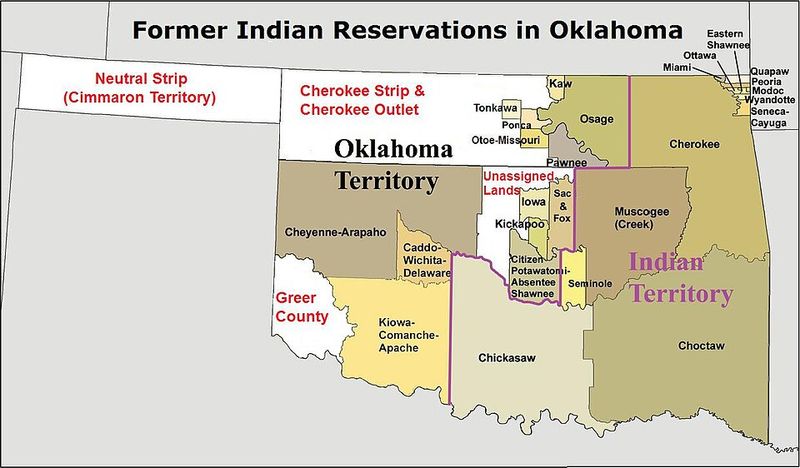

The Sauk Were Forced West Multiple Times

Imagine being forced to move once, rebuilding your life, then being forced to move again. That was the Sauk experience throughout the 19th century.

After losing their Illinois homeland following the Black Hawk War, the tribe relocated to Iowa in the 1830s. They hoped this would be their permanent home, but American expansion had other plans.

Within two decades, settlers wanted Iowa too. In the 1840s and 1850s, the Sauk were pushed again, this time into Kansas Territory.

Once more they established communities, farms, and tried to adapt to new surroundings. But Kansas became increasingly desirable to American settlers, and pressure mounted for another removal.

The final major relocation came after the Civil War when many Sauk were moved to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Each move meant abandoning homes, graves of ancestors, and familiar landscapes.

Each relocation disrupted communities and made traditional ways of life harder to maintain. The Sauk story of multiple forced removals reflected the broader pattern of broken promises and continuous displacement that characterized federal Indian policy throughout the 1800s.

Today, the Sauk Nation Still Exists

Survival is sometimes the greatest victory. Despite everything the Sauk people endured, they didn’t disappear.

Today, three federally recognized Sauk communities maintain their identity and sovereignty. The Sac & Fox Nation of Oklahoma, headquartered near Stroud, Oklahoma, represents the largest group.

They operate tribal businesses, maintain cultural programs, and govern their own affairs.

In Iowa, the Sac & Fox Tribe of the Mississippi preserves their heritage near Tama. This community actually purchased their own land in Iowa during the 1800s, allowing them to remain closer to their ancestral homeland.

In Kansas and Nebraska, the Sac & Fox Nation of Missouri continues their traditions and tribal governance.

These modern Sauk communities face contemporary challenges including economic development, healthcare access, and cultural preservation. Young people balance traditional knowledge with modern education.

Tribal governments work to maintain sovereignty while navigating complex relationships with state and federal authorities. The Sauk story didn’t end with Black Hawk or forced removal but continues today with resilient communities determined to preserve their identity for future generations.

Their Story Challenges the Myth of Peaceful Expansion

American history textbooks often describe westward expansion with words like manifest destiny and pioneer spirit, suggesting an inevitable and relatively peaceful process. The Sauk experience tells a very different story.

Their history reveals that American territorial growth came through broken treaties, military force, and systematic displacement of Indigenous peoples.

The 1804 treaty signed without proper authority, the Black Hawk War fought over disputed land claims, and multiple forced relocations weren’t exceptions but typical patterns. What happened to the Sauk happened to dozens of other tribes across the continent.

Peaceful expansion is a comforting myth, but the reality involved violence, deception, and cultural destruction.

Understanding the Sauk story matters because it challenges how we think about American history. It forces us to acknowledge that the nation’s growth came at tremendous cost to Indigenous peoples.

This doesn’t mean rejecting American history but seeing it more completely and honestly. The Sauk helped shape early American history not just through their presence but through their resistance, their suffering, and their survival, revealing uncomfortable truths about how the United States actually expanded westward.