Walk the prairies and river bluffs of the Midwest, and you are never far from a hidden skyline of earth. The Mound Builders shaped cities, rituals, and stories in soil, yet most people drive past without ever knowing.

This list pulls back the grass to show you the engineering, astronomy, trade, and power that defined these Indigenous societies. By the end, you will see the Midwest as an ancient landscape of planners, farmers, and stargazers whose legacy still rises above us.

1. They were multiple cultures

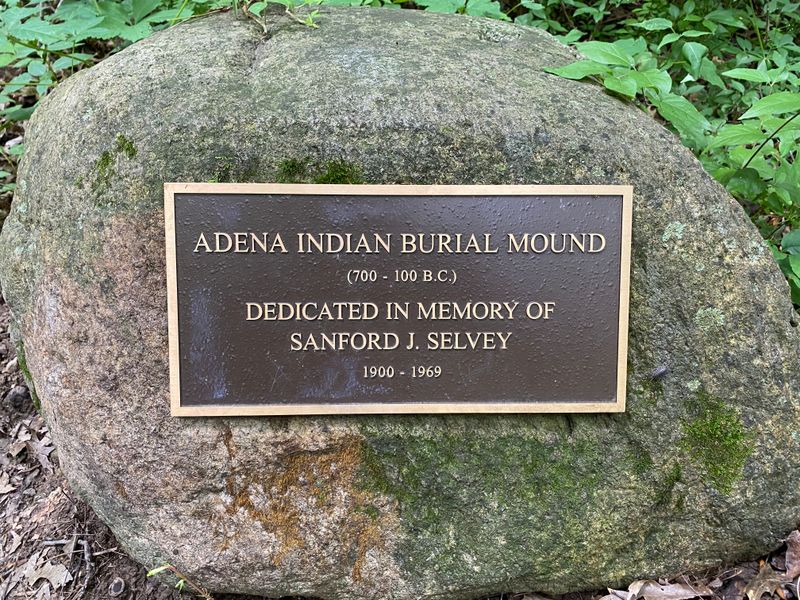

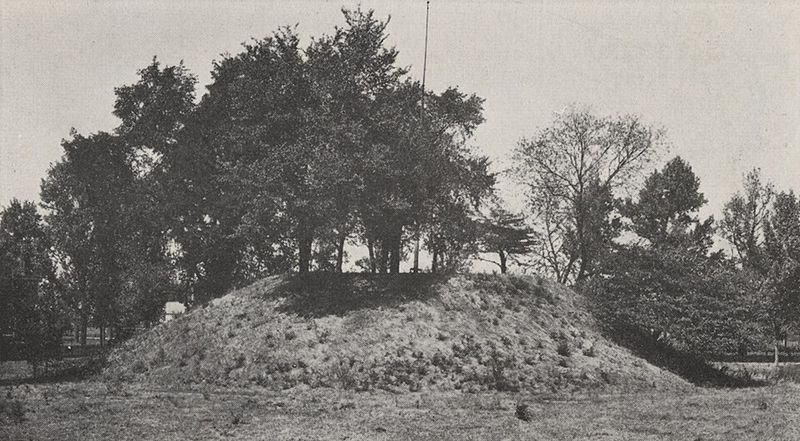

Mound Builders is a modern umbrella for several distinct cultures across time, not a single people. Archaeologists typically use Adena for early Woodland groups in the Ohio Valley, Hopewell for later mound builders known for artistry and earthworks, and Mississippian for the temple mound cities that flourished closer to 1000 to 1500 CE.

Each culture had its own settlement patterns, craft traditions, and cosmologies. When you hear Mound Builders, think families of ideas moving through generations and rivers.

Adena created conical burial mounds, Hopewell engineered geometric embankments, and Mississippian societies raised flat topped platform mounds for leaders and shrines. Lumping them together hides their local genius.

It helps to picture a long relay rather than a single sprint. Techniques passed forward, influences blended, and communities adapted to climate and trade.

That is why sites feel similar yet unmistakably regional.

2. Their timeline spans millennia

Mound construction in North America stretches across thousands of years. Early precedents appear by the late Archaic, and Woodland era earthworks expand from around 1000 BCE.

The Mississippian world then rises after 1000 CE and continues into the 1500s, pressing right up to European arrival. For you, the takeaway is simple.

These were not brief experiments but sustained traditions with deep memory. Skills like basket loading soil, planning causeways, and aligning embankments were taught across generations, refined in each community.

Consider how long it takes to build a city. Now extend that patience across centuries, and you begin to appreciate the endurance involved.

Radiocarbon dates, ceramic styles, and dietary traces anchor the chronology, while oral histories preserve meanings. The long arc shows resilience, innovation, and the ability to rebuild after floods, droughts, or political shifts.

3. Mounds served many purposes

Not every mound is a tomb. Some are conical burials containing carefully arranged remains and grave goods.

Others are platform mounds that once supported temples, elite residences, or council houses, rising above plazas where ceremonies and markets unfolded. You can think of these as a city’s zoning made of earth.

There are even embankments and geometric enclosures that marked sacred spaces, guided processions, or tracked celestial events. Low ridges may look unimpressive until excavations reveal posts, offerings, and patterned soils.

Understanding function changes how you visit. Instead of a mysterious hill, you may be standing on a civic center, a theater of diplomacy, or a place of mourning.

Respectful tourism means staying on paths, reading site signage, and recognizing that many mounds are active sacred places for descendant communities who continue to pray and gather there.

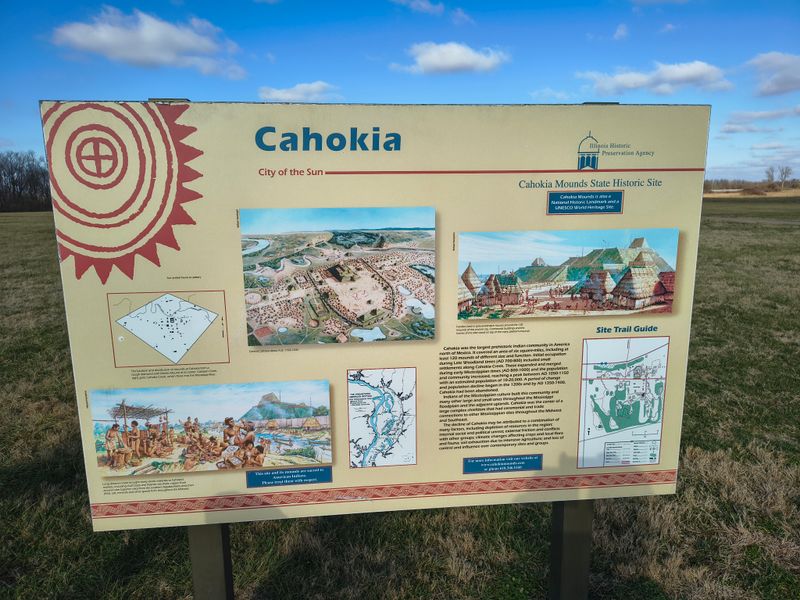

4. Cahokia was a metropolis

Across the river from present day St. Louis, Cahokia erupted into a true city by around 1050 CE. At its height, it hosted tens of thousands, with estimates often placed around 15,000 to 20,000 in the core and more in surrounding settlements.

That scale rivaled European centers like London during the same era. Walk the site today and you will see broad plazas, borrow pits, and the footprints of neighborhoods.

Imagine food arriving in baskets, shell beads clinking in markets, and rituals timed to the sun at Woodhenge. Urban planning, labor mobilization, and long distance trade all converged here.

For urbanists, Cahokia is a case study in preindustrial logistics. For travelers, it is a reminder that American city building predates skyscrapers.

The city’s rise also signals regional integration, with feeder villages, farmland, and craft specialists linked into a shared project.

5. Monks Mound shows massive planning

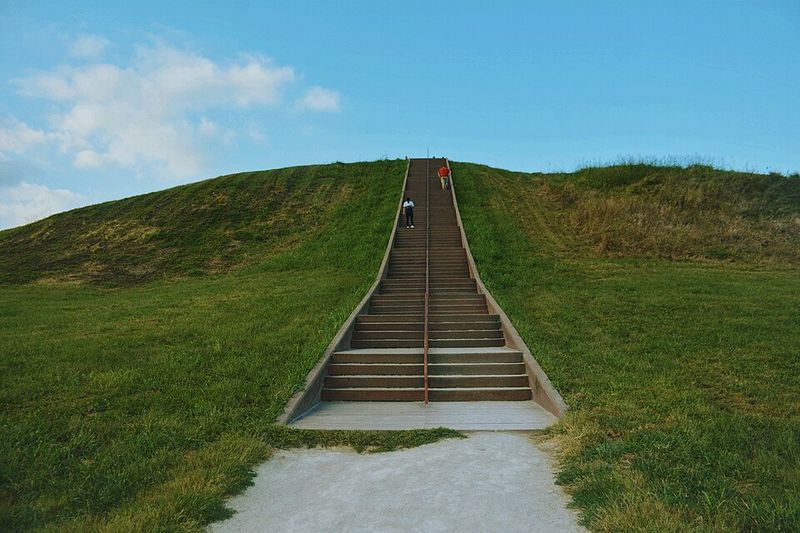

Monks Mound dominates the floodplain at Cahokia. Standing roughly 30 meters high with a base larger than the Great Pyramid of Giza, it required staggering quantities of soil moved by hand.

Estimates suggest tens of millions of basket loads layered in engineered lifts to shed water and resist slumping. Think about scheduling that workforce.

Laborers needed food, tools, supervisors, and seasons without floods. Soil types were selected and arranged, a quiet engineering feat learned from prior experiments across the region.

For you as a visitor, the climb is a lesson in logistics and authority. Platform mounds were stages where leaders could be seen, where ceremonies anchored civic identity.

The endurance of Monks Mound testifies to planning, maintenance, and communal pride, reminding us that sustainability once meant knowing how earth breathes after rain.

6. They built with astronomical precision

Many earthworks encode the sky. At Cahokia, a timber circle called Woodhenge marked solstices and equinoxes, aligning sunrise points with posts and the mound horizon.

Across the Midwest, embankments and mound axes often key to celestial events, reinforcing calendars and ritual timing. Why does this matter for you?

Astronomy helped schedule planting, ceremonies, and diplomacy. Alignments show careful observation, repeated over generations, and a cultural message that time is communal, not private.

Researchers use GIS, horizon surveys, and archaeoastronomy to test these patterns. When alignments recur at multiple sites, chance looks unlikely.

As a practical tip, visit at dawn near solstices if permitted, stand where sightlines converge, and let the landscape act as a teaching instrument that still works.

7. Trade networks connected continents

Artifacts from mound contexts speak of long roads and trusted partners. You get Great Lakes copper hammered into glittering plates, Gulf Coast marine shell carved into gorgets, and obsidian traced to the Rocky Mountains using geochemical signatures.

These are proof of social agreements, obligations, and shared symbols. Consider the logistics.

Canoes moved along rivers, portages linked watersheds, and travelers carried stories with goods. The spread of iconography, like birdman motifs, suggests that ideas traveled as eagerly as materials.

For a modern parallel, think of supply chains and brand networks. Archaeology has the receipts in isotope values and source analyses.

The scope is continental, showing that mound centers were not isolated villages but hubs within exchange webs that stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf and beyond.

8. Agriculture powered growth

Maize, beans, and squash transformed the Midwest into a food engine. Surplus meant more than full bellies.

It freed labor for mound construction, craft specialization, and expanded leadership roles, supporting dense neighborhoods and regional festivals. If you garden, you know timing and soil matter.

Farmers managed floodplain fertility, stored harvests in pits, and rotated fields to balance yields. Stable calories supported infants and elders, swelling populations and creating a feedback loop between food and public works.

Recent syntheses estimate precontact populations at Cahokia’s peak in the tens of thousands, with regional networks larger. Agricultural intensity correlates with mound construction pulses visible in soil layers.

For you, the lesson is that cities rise when kitchens thrive. Food was civic infrastructure, just like plazas and palisades.

9. Hierarchies shaped daily life

Platform mounds created elevated stages for leaders, priests, and ceremonies, signaling political and spiritual authority. Houses atop mounds contrasted with everyday dwellings in surrounding neighborhoods.

Burial goods, feasting remains, and iconography point to ranked societies where status structured obligations and privileges. You can read hierarchy in architecture.

Stairways frame controlled access, plazas orchestrate gatherings, and palisades define insiders and outsiders. This was not simply top down rule.

Councils, kin networks, and ritual specialists negotiated power through gift exchange and public spectacle. For visitors, interpreting hierarchy helps explain site layouts.

For readers, it underscores that governance in the precontact Midwest was sophisticated, contested, and ritualized. The city was a theater where rank had a seat and responsibility, visible in every terrace and doorway.

10. Environmental stress drove decline

No single disaster erased mound centers. Instead, environmental stress piled up.

Floods altered fields, droughts pinched harvests, and soils tired under intensive use. Political tensions likely sharpened when granaries thinned and alliances frayed.

Climate records from tree rings show megadrought intervals in the 12th to 14th centuries across parts of North America. Archaeologists track shifting settlement patterns, palisade rebuilds, and diet changes in the centuries before contact.

It looks like resilience met its limits in certain places at certain times. Your practical takeaway is to read decline as adaptation and movement.

Some communities dispersed, others reorganized. The story is complex, cautioning against neat collapse narratives and inviting empathy for leaders and farmers who faced stacked risks.

11. Myths once replaced facts

In the 19th century, many settlers refused to credit Native peoples with mound building. The so called Moundbuilder Myth imagined lost races or Old World visitors as the true architects.

This fiction justified land seizure by denying Indigenous achievement. Archaeology dismantled the myth through evidence.

Stratigraphy, radiocarbon dating, and continuity with descendant communities showed clear Native authorship. Museums and state agencies now correct the record, and tribal voices lead interpretation at many sites.

When you encounter an old sign or rumor, you can ask who benefits from the story. Choosing facts over fantasy supports respectful stewardship.

It also opens richer conversations with tribes whose oral traditions long remembered what outsiders tried to forget.

12. Effigy mounds and sacred shapes

In the Upper Midwest, some builders shaped earth into animals and spirit beings. Effigy mounds curl like bears, spread like birds, or snake across ridges, blending art, cosmology, and territory.

They often overlook water or frame pathways, turning movement into ceremony. For you, the effect is visceral from above.

On the ground, they can feel low and humble. Aerial photographs and drone footage reveal the full bodies, so check visitor centers for imagery that orients your walk.

Archaeologists debate functions, from burial to boundary and story map. What is clear is intention.

These shapes carried meaning for communities who maintained them. Respect the forms by staying on designated routes and remembering that many effigy landscapes remain active sacred sites today.

13. Their legacy still stands

Thousands of mounds remain across the Midwest, though many were destroyed by farming and development. Protected places like Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site and Effigy Mounds National Monument offer trail networks, exhibits, and ranger talks.

Preservation groups and tribes are leading restorations, burns, and erosion control. Here is a statistic to underscore urgency.

In some states, more than half of recorded mounds were damaged or leveled by the early 20th century, a loss that cannot be undone. Yet visitation numbers and funding for conservation are rising, reflecting a public ready to learn.

Your role can be simple. Visit respectfully, support local museums, and amplify Indigenous voices who steward these landscapes.

The mounds endure as classrooms, memorials, and proof that North America’s first cities grew from prairie soil and community resolve.