Native American history stretches back thousands of years, filled with rich traditions, powerful stories, and vibrant cultures that continue to thrive today. Museums across North America work hard to preserve these important histories, giving visitors a chance to learn about Indigenous peoples through artifacts, art, and storytelling.

Whether you’re curious about ancient pottery, ceremonial regalia, or modern Native art, these institutions offer windows into worlds that deserve recognition and respect. Here are fourteen cultural museums where Native American history comes alive.

National Museum of the American Indian — Washington, D.C.

Standing on the National Mall, this Smithsonian institution holds over 800,000 objects representing Indigenous peoples from the Arctic to Latin America. The building itself, with its curved limestone walls and native landscaping, reflects Indigenous architectural philosophies and connection to the land.

Inside, thematic galleries organized by cultural regions—Northeast Woodlands, Plains, Southwest—invite visitors to explore diverse tribal histories.

Ceremonial objects, traditional clothing, and contemporary art fill the exhibition halls, each piece accompanied by Indigenous narratives rather than external interpretations. Special exhibitions use immersive media to bring creation stories and ancestral technologies to life, making history feel immediate and relevant.

Visitors hear directly from Native voices through video testimonies and audio recordings.

The museum doesn’t treat Indigenous culture as frozen in time but emphasizes continuity from past to present. Educational programs, film screenings, and cultural demonstrations happen regularly, creating opportunities for deeper engagement.

The building’s design even includes a resource center where researchers can access archives and collections.

For anyone wanting to understand the breadth of Native American experiences, this museum serves as an essential starting point. Its commitment to Indigenous-led storytelling sets it apart from older institutions that once displayed Native artifacts without proper context or respect.

National Museum of the American Indian — New York, NY

Housed in the stunning Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in lower Manhattan, this sister location focuses on Indigenous art through rotating exhibitions that change throughout the year.

The building’s Beaux-Arts architecture provides an unexpected backdrop for world-class collections of regalia, textiles, and ceremonial items from tribes across the Americas. Walking through these galleries feels like discovering hidden treasures in the heart of the city.

The permanent exhibit ‘Infinity of Nations’ showcases cultural diversity among Indigenous peoples, displaying over 700 works from more than 150 communities. Visitors see how different tribes developed unique artistic traditions while maintaining connections through trade and shared histories.

Contemporary galleries highlight how modern Native artists blend traditional techniques with new materials and concepts.

This New York location emphasizes Indigenous experiences in urban and colonial contexts, encouraging visitors to recognize Native peoples as active participants in city life rather than distant historical figures. Educational programs connect local school groups with Indigenous educators and artists.

The museum store features authentic Native-made jewelry, pottery, and books.

Its location in the Custom House—once the center of colonial trade and taxation—adds layers of meaning to exhibitions about Indigenous resilience and survival. Free admission makes it accessible to everyone curious about Native cultures.

First Americans Museum — Oklahoma City, OK

Oklahoma is home to 39 federally recognized tribal nations, making it one of the most culturally diverse Indigenous regions in the country. The First Americans Museum opened in 2021 after decades of planning and collaboration with these tribal communities.

Its striking contemporary architecture sits along the Oklahoma River, creating a landmark visible across the city.

Interactive galleries use sound, touch, and visual elements to immerse visitors in language, music, art, and stories from Oklahoma’s tribes. You might hear traditional songs playing while examining intricate beadwork, or watch videos of tribal members explaining ceremonial practices in their own words.

The museum emphasizes that Native cultures aren’t relics but living, evolving traditions.

Exhibitions explore difficult topics like forced removal and boarding schools alongside celebrations of tribal sovereignty and cultural resilience. The design process involved extensive consultation with tribal leaders to ensure respectful, accurate representation.

A restaurant on-site serves Indigenous-inspired cuisine, incorporating traditional ingredients and cooking methods.

Special programming includes language classes, artist talks, and seasonal festivals that bring tribal communities together. The museum’s mission centers on amplifying Indigenous voices rather than speaking for them.

For visitors unfamiliar with Oklahoma’s complex Native history, this museum provides essential context and understanding.

Heard Museum — Phoenix, AZ

Since 1929, the Heard Museum has specialized in Southwestern tribal cultures, building one of the world’s finest collections of Indigenous art from this region. Its holdings include thousands of pieces of pottery, jewelry, textiles, and an especially renowned collection of Hopi katsina dolls.

The museum grounds feature beautiful courtyards with sculptures and outdoor installations.

What sets the Heard apart is its deep commitment to Indigenous collaboration in every aspect of exhibition development. Tribal members serve as consultants, ensuring that sacred objects are displayed respectfully and that explanatory text reflects Native perspectives.

Exhibits explore ceremonial life, cosmology, and tribal sovereignty without reducing cultures to simple stereotypes.

Contemporary Native artists have gallery space alongside historical artifacts, demonstrating how traditions adapt and thrive in modern contexts. You might see ancient pottery displayed near cutting-edge mixed-media installations by current Indigenous artists.

The museum hosts an annual Indian Fair & Market that attracts thousands of visitors and features over 600 Native artists.

Educational programs include lectures, performances, and hands-on workshops where visitors can learn traditional crafts from Native practitioners. The museum store sells authentic Native-made items, with proceeds supporting Indigenous artists.

For understanding both ancient Southwestern traditions and contemporary Native artistic expression, the Heard Museum stands unmatched.

Abbe Museum — Bar Harbor & Mount Desert Island, ME

Maine’s Indigenous peoples—the Wabanaki nations including Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Mi’kmaq—have called this region home for over 12,000 years. The Abbe Museum operates two locations on Mount Desert Island, dedicated to preserving and sharing Wabanaki heritage.

Its collections include archaeological artifacts, traditional crafts, clothing, and cultural archives that tell stories often overlooked in mainstream American history.

Exhibitions trace Wabanaki life from pre-contact times through European settlement and into contemporary experiences. Visitors learn about traditional technologies like birch bark canoe construction and ash-splint basketry, both still practiced today.

The museum doesn’t shy away from difficult topics like land loss and cultural suppression.

What makes the Abbe special is its commitment to centering Wabanaki voices in all interpretive materials. Tribal members contribute to exhibition text, select objects for display, and lead educational programs.

The museum’s Native Arts Festival brings together Wabanaki artists and performers each year, celebrating living culture.

Research collections available to scholars include thousands of photographs, documents, and artifacts that help piece together regional Indigenous history. The museum also advocates for Wabanaki rights and recognition in Maine.

For anyone visiting coastal Maine, the Abbe Museum offers crucial context about the region’s First Peoples and their continuing presence.

Journey Museum & Learning Center — Rapid City, SD

Rapid City sits at the edge of the Black Hills, a landscape sacred to the Lakota and other Plains tribes. The Journey Museum integrates Native histories with geological and pioneer narratives, creating a comprehensive view of the region’s past.

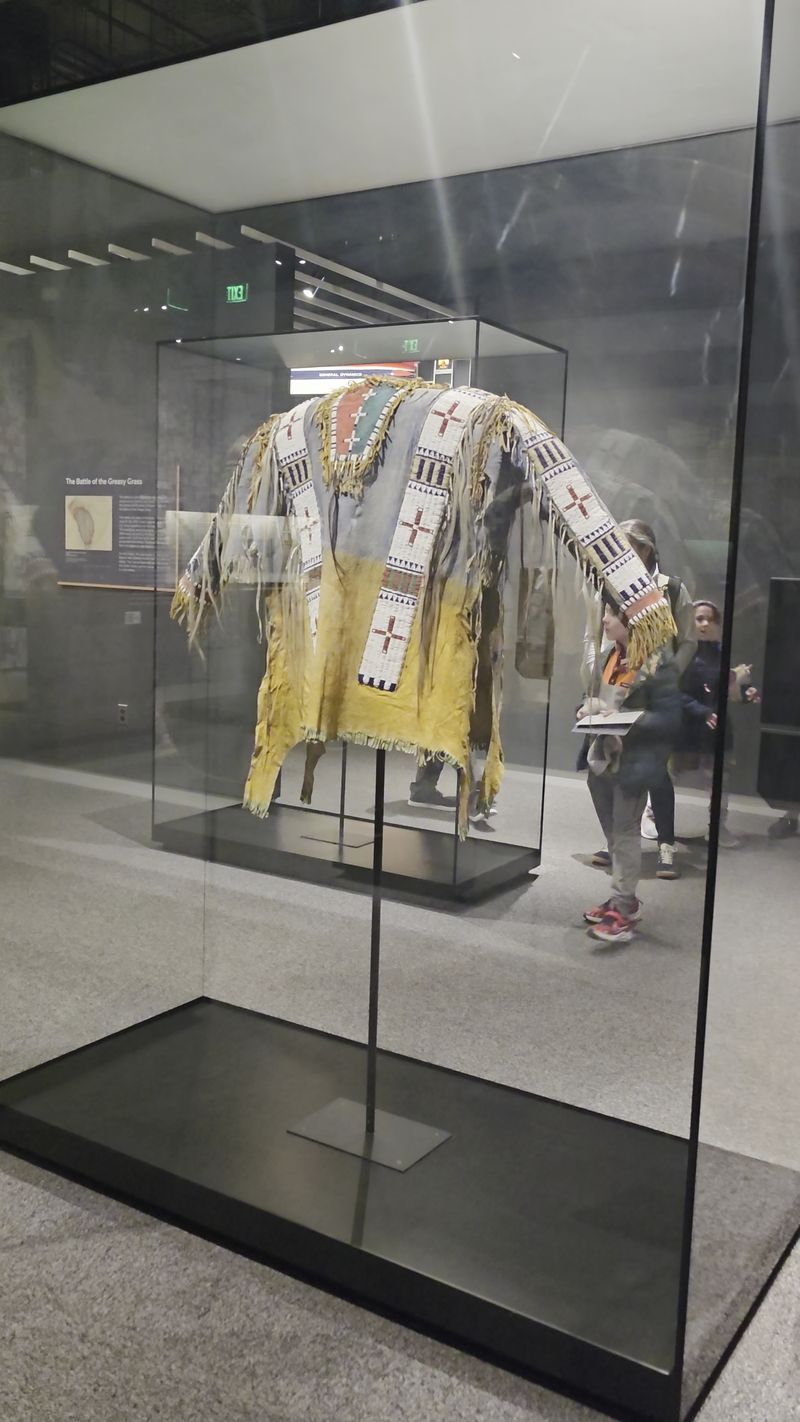

Visitors encounter archaeological artifacts, traditional regalia, and multimedia presentations that contextualize Indigenous persistence through centuries of change.

Exhibits explore Lakota lifeways, including the central importance of buffalo to Plains cultures. You’ll see clothing decorated with intricate beadwork, weapons used for hunting, and ceremonial items that reveal spiritual practices.

Oral histories recorded by tribal elders add personal dimensions to historical events.

The museum doesn’t romanticize Native life or ignore the devastating impacts of colonization and forced relocation. Exhibitions address the Wounded Knee Massacre, reservation life, and ongoing struggles for sovereignty and recognition.

Contemporary sections highlight modern Lakota artists and activists who continue fighting for their people.

Natural history collections help visitors understand how geography shaped Indigenous cultures in this region. The museum’s location near Mount Rushmore and other tourist destinations makes it an important counterpoint to simplified narratives about Western expansion.

Educational programs bring tribal members into classrooms and public spaces to share their perspectives directly.

Tantaquidgeon Museum — Uncasville, CT

Founded in 1931 by members of the Mohegan Tribe, this small museum holds the distinction of being one of the oldest continuously operated Native-run museums in the United States. The Tantaquidgeon family built it to preserve their people’s traditions, tools, ceremonial items, and oral histories when outside institutions showed little interest in Northeastern Indigenous cultures.

Its modest size belies its profound importance.

Collections include baskets woven with traditional techniques passed down through generations, clothing decorated with quillwork and beadwork, and medicine implements used by tribal healers. Each object carries stories about Mohegan life, spirituality, and connection to the land.

The museum embodies Indigenous stewardship of cultural heritage.

Unlike large institutions with extensive staff and funding, the Tantaquidgeon Museum operates through tribal dedication and community support. Guided tours often include tribal members who share personal connections to displayed objects.

Visitors gain insights into a Northeastern Indigenous culture often overlooked in broader national narratives focused on Western or Southwestern tribes.

The museum’s survival through nearly a century demonstrates Mohegan resilience and commitment to cultural preservation. Its archives include photographs, documents, and recordings that researchers use to understand regional Native history.

For anyone interested in Indigenous New England, this community-centered museum offers irreplaceable perspectives and authentic connections to living Mohegan culture.

Tomaquag Indian Memorial Museum — Exeter, RI

Narragansett and Pokanoket leaders founded this museum in 1958 to preserve Native histories of southeastern New England, a region where Indigenous presence is often forgotten or minimized. The Tomaquag Museum combines indoor exhibitions with outdoor cultural features, creating immersive educational experiences.

Visitors can explore a traditional wetu (dwelling) and Three Sisters gardens that demonstrate sustainable Indigenous agricultural practices.

Collections emphasize traditional crafts like ash-splint basketry, which remains an important art form among New England tribes. Historical archives include photographs, documents, and objects that trace Indigenous life through centuries of colonization and survival.

The museum’s focus on living traditions distinguishes it from institutions that present Native cultures as extinct.

Educational programs bring Indigenous perspectives into schools throughout Rhode Island, correcting common misconceptions about regional history. The museum challenges Thanksgiving myths and other simplified narratives that erase Native experiences.

Workshops teach traditional skills like basket weaving and beadwork to both Native and non-Native participants.

Tomaquag advocates for accurate representation of Indigenous peoples in education and public discourse. Its staff includes tribal members who ensure that exhibitions reflect community values and knowledge.

The museum’s relatively small size allows for personal interactions and meaningful conversations about Native histories. For understanding Indigenous New England cultures beyond stereotypes, Tomaquag serves as an essential resource.

Southern Plains Indian Museum — Anadarko, OK

Anadarko, Oklahoma, sits in the heart of Southern Plains territory, home to Caddo, Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, Wichita, and other tribes. This museum specializes in artistic and cultural works from these nations, showcasing both historical and contemporary pieces.

Collections include elaborate dance regalia decorated with ribbons, beads, and feathers that demonstrate the skill and creativity of Plains artists.

Traditional clothing on display reveals how different tribes developed distinct styles while sharing certain aesthetic principles. Jewelry pieces made from silver, turquoise, and other materials show trade connections across vast distances.

The museum’s dioramas recreate historical scenes, helping visitors visualize daily life on the Southern Plains.

Contemporary Native artists from the region have gallery space to display paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media works that blend traditional motifs with modern techniques. These pieces challenge stereotypes about Native art being frozen in the past.

Artist talks and demonstrations happen regularly, allowing visitors to meet creators and learn about their processes.

The museum operates under the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, a federal agency that promotes authentic Native-made arts. This ensures that items in the museum store come from actual Indigenous artists rather than mass-produced imitations.

For understanding Southern Plains cultures through artistic expression, this specialized museum offers concentrated expertise and beautiful collections.

Museum of Northern Arizona — Flagstaff, AZ

Flagstaff’s location on the Colorado Plateau places it near lands traditionally inhabited by Hopi, Zuni, Navajo, and Pai peoples. The Museum of Northern Arizona preserves cultural histories of these tribes alongside natural history collections that explore the region’s unique geology and ecology.

Its Ethnology Gallery highlights traditional arts, ceremonial objects, and everyday items that reveal how Indigenous peoples adapted to this rugged landscape.

Pottery collections include ancient pieces from ancestral Pueblo sites and contemporary works by living artists. Navajo textiles demonstrate weaving techniques passed through generations, with patterns carrying cultural significance.

Hopi katsina dolls and ceremonial items are displayed with careful attention to tribal protocols about sacred objects.

What distinguishes this museum is its commitment to developing exhibitions in consultation with tribal members. Indigenous advisors review interpretive text, select appropriate objects for display, and ensure cultural integrity throughout.

This collaborative approach has built trust between the museum and surrounding Native communities.

Annual heritage programs celebrate specific tribal cultures through art markets, demonstrations, and performances. The Hopi Festival of Arts and Culture and Navajo Festival of Arts draw thousands of visitors each year.

Research collections support scholars studying Colorado Plateau archaeology and ethnography. For understanding how Indigenous peoples thrived in challenging environments while maintaining rich cultural traditions, this museum provides essential context.

Indian Pueblo Cultural Center — Albuquerque, NM

New Mexico’s 19 Pueblo tribes—including Acoma, Zuni, Taos, and others—maintain distinct languages, traditions, and identities while sharing common cultural threads. The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque was created by these tribes to tell their own stories rather than having outsiders interpret their cultures.

Exhibitions feature murals, pottery, textiles, and interpretive displays exploring ancestral Pueblo life and contemporary achievements.

Visitors learn about religious ceremonies, agricultural practices, and architectural traditions that have sustained Pueblo peoples for centuries. The center doesn’t treat these as historical curiosities but as living practices continuing today.

Dance performances by tribal members bring cultural expressions to life, accompanied by explanations of their significance.

The museum’s restaurant serves traditional Pueblo foods, giving visitors tastes of Indigenous cuisine made with corn, beans, squash, and other native ingredients. Annual festivals bring together members from different Pueblos for celebrations of shared heritage.

Educational programs connect tribal elders with younger generations, helping preserve languages and traditional knowledge.

A museum store sells authentic Pueblo-made pottery, jewelry, and textiles, with proceeds supporting tribal artists and cultural programs. The center advocates for Pueblo rights and sovereignty while educating the public about these nations’ contributions to regional culture.

For understanding the diversity and continuity of Pueblo cultures, this tribally operated institution offers unmatched authenticity.

Museum of Indian Arts & Culture — Santa Fe, NM

Santa Fe’s reputation as an art center extends back centuries to Indigenous artistic traditions that continue thriving today. The Museum of Indian Arts & Culture focuses specifically on Southwestern Native cultures, housing world-class collections of pottery, jewelry, textiles, and ceremonial objects.

Its location in Museum Hill makes it part of a larger cultural complex that attracts art enthusiasts from around the globe.

Permanent exhibitions trace the development of Southwestern Indigenous arts from ancient times to contemporary practices. Visitors see how pottery styles evolved across different pueblos, how silversmithing techniques were adapted and transformed, and how weaving traditions incorporated new materials while maintaining traditional patterns.

The museum doesn’t separate historical and contemporary work, emphasizing artistic continuity.

Public lectures, artist residencies, and temporary exhibitions deepen engagement with Native perspectives and creative practices. Indigenous artists often demonstrate techniques in the museum, allowing visitors to watch traditional crafts being made.

The museum’s interdisciplinary approach connects art with archaeology, anthropology, and history for comprehensive understanding.

Research collections support scholars studying Southwestern Indigenous cultures, with extensive archives of photographs, field notes, and documented artifacts. The museum works closely with tribal communities to ensure respectful treatment of sacred or sensitive materials.

For anyone serious about understanding Southwestern Native arts in both historical and contemporary contexts, this institution offers unparalleled depth and expertise.

Millicent Rogers Museum — Taos, NM

Taos, New Mexico, sits in a region where Indigenous, Hispanic, and Anglo cultures have intermingled for centuries, creating unique artistic traditions. The Millicent Rogers Museum, though smaller than many institutions on this list, showcases exceptional collections of Native American and Hispanic arts.

Its emphasis on ceramics, jewelry, textiles, and regional Indigenous crafts reveals the interwoven cultural histories of Northern New Mexico.

The museum was founded to house the collection of Millicent Rogers, a fashion icon and art collector who moved to Taos in the 1940s and became fascinated with local Indigenous and Hispanic arts. Her collection included pottery from nearby pueblos, Navajo textiles, and jewelry by Native silversmiths.

The museum has expanded significantly since then.

Exhibitions explore how different cultural groups influenced each other’s artistic practices while maintaining distinct identities. You might see Spanish colonial santos displayed near Pueblo pottery, revealing both differences and connections.

Temporary exhibitions often feature contemporary Native artists from the region.

The museum’s intimate scale allows for close examination of intricate details in jewelry, weaving, and pottery that might get overlooked in larger institutions. Educational programs connect visitors with local Indigenous and Hispanic artists through demonstrations and talks.

For understanding the complex cultural landscape of Northern New Mexico and how Native traditions fit within it, this museum offers valuable perspectives and beautiful examples of Indigenous artistry.

Buffalo Nations Luxton Museum — Banff, Alberta, Canada

Crossing into Canada, the Buffalo Nations Luxton Museum in Banff, Alberta, preserves Indigenous histories of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Nakoda Nations, and Tsuut’ina Nation. These First Nations peoples inhabited the lands around the Canadian Rockies long before European contact, developing cultures adapted to mountain and prairie environments.

The museum’s collections include artifacts, artwork, and interpretive materials celebrating First Nations heritage.

Exhibitions explore traditional lifeways including buffalo hunting, which sustained Plains peoples for generations. Visitors see clothing made from buffalo hides, tools crafted from bone and stone, and ceremonial items used in spiritual practices.

The museum explains how the near-extinction of buffalo herds devastated Indigenous economies and cultures.

Located in a tourist town famous for its natural beauty, the museum provides crucial context about the region’s original inhabitants. Many visitors come to Banff for outdoor recreation without realizing they’re traveling through territories that remain culturally significant to First Nations peoples.

The museum works to raise awareness about Indigenous presence and rights.

Collections also document exchange relationships between different First Nations groups and later interactions with European fur traders. Contemporary sections highlight modern First Nations artists and activists working to preserve languages and traditions.

For understanding Indigenous perspectives on the Canadian Rockies region and gaining a broader North American view of Native histories, this museum offers important Canadian Indigenous perspectives often missing from U.S.-focused narratives.