Hoaxes thrive where curiosity meets limited verification, and history is full of examples that fooled smart people. This list walks you through 15 famous deceptions, how they worked, and why they spread so widely.

You will see patterns repeat across newspapers, radio, TV, and the internet. By the end, you will recognize the red flags that keep resurfacing in new forms.

1. The Great Moon Hoax (1835)

In 1835, the New York Sun ran a sensational series claiming a renowned astronomer had observed life on the Moon. The articles described bat-like humanoids, blue lakes, lush forests, and bizarre creatures seen through a powerful new telescope.

Readers were captivated, and circulation soared as the paper released installment after installment, each more vivid than the last.

The hoax succeeded because it blended scientific language, a trusted figure, and precise details that felt plausible to a public excited by astronomy. Newspapers competed fiercely, and reprints spread the story across the United States and beyond.

Few had the tools to verify astronomical claims, and many wanted to believe humanity had cosmic neighbors.

Eventually, skeptics and scientists exposed the series as fiction, admitting it was crafted to entertain and sell papers. The Sun never fully apologized, but the public learned a lasting lesson about anonymous authority and sensational reporting.

Today, the Great Moon Hoax is remembered as an early example of mass media’s power to shape belief. When a claim leans on prestige and novelty, pause and ask for primary sources.

Curiosity is healthy, but verification is essential.

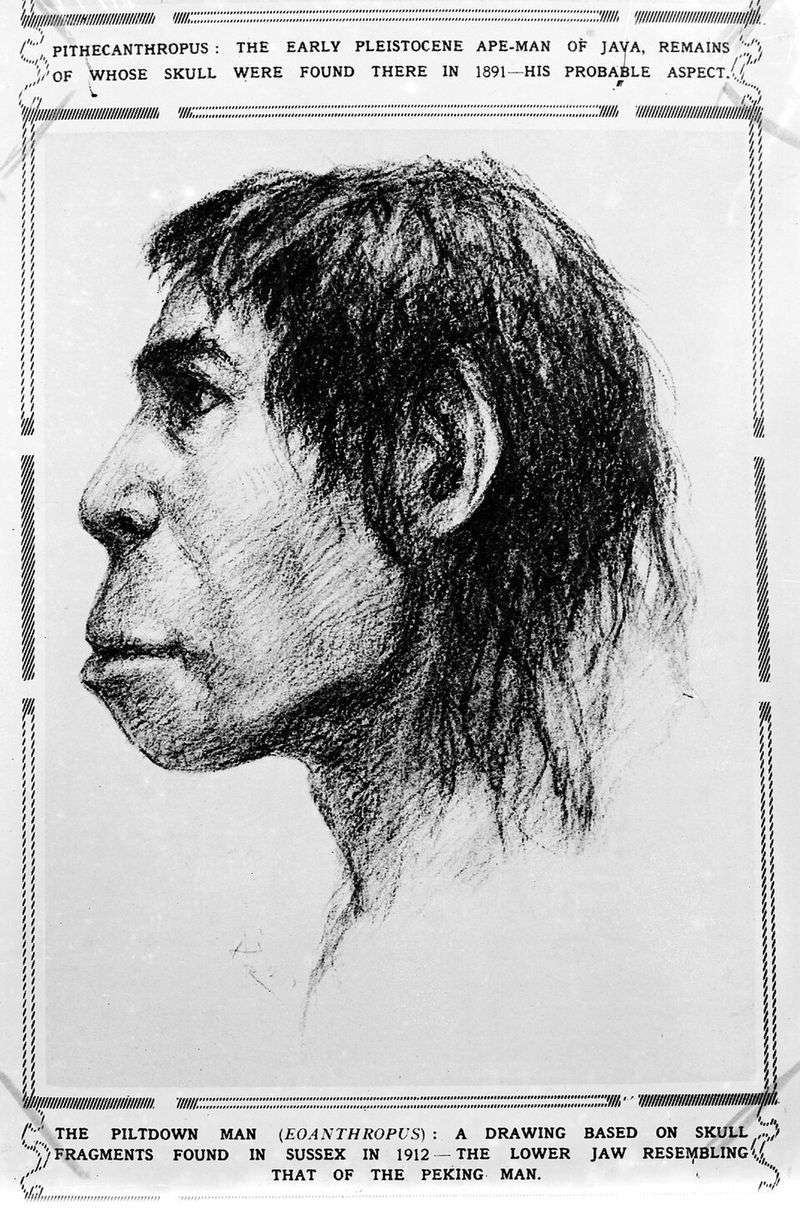

2. Piltdown Man (1912)

In 1912, amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson announced a monumental discovery from a gravel pit in Sussex: the missing link between apes and humans. The skull fragments and jawbone, dubbed Piltdown Man, seemed to confirm a human-like brain with an apelike jaw.

Prestigious British institutions accepted the find, and casts circulated to universities worldwide.

Piltdown fit expectations that human evolution might have centered in England, and that bias helped it endure. For decades, textbooks cited Piltdown as evidence, while contradictory fossils from Africa were dismissed.

Scientific prestige, nationalist pride, and limited access to the original bones shielded the fraud from scrutiny.

In 1953, modern tests revealed the truth: a medieval human skull paired with an orangutan jaw, stained and filed to fit. The exposure embarrassed museums and reminded researchers to test extraordinary finds rigorously.

Today, Piltdown is a cautionary tale about confirmation bias and selective evidence. When a result perfectly matches hopes, double the skepticism.

Replication, open data, and independent testing are not bureaucratic hurdles. They are the safeguards that keep science honest and self-correcting over time.

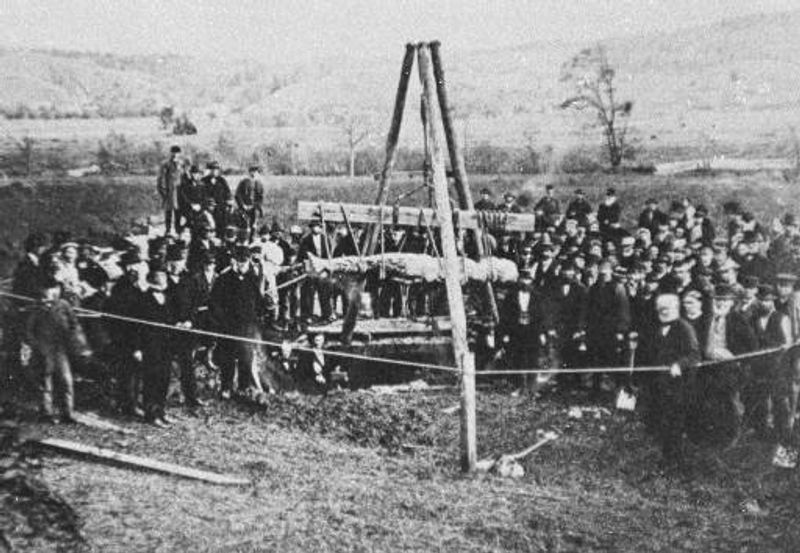

3. The Cardiff Giant (1869)

In 1869, laborers in Cardiff, New York unearthed a ten-foot stone figure that looked like a petrified man. News raced through the region, and crowds paid admission to view the marvel.

The giant’s realistic features and weathered surface convinced many it was a prehistoric relic or biblical curiosity.

The statue, however, was a carefully carved gypsum figure commissioned by George Hull. He created it to mock literal interpretations of scripture and to profit from public fascination.

Local businessmen amplified the spectacle, and rival showmen even produced competing giants, further muddying the waters of truth.

Experts soon spotted tool marks and inconsistent geology, and the hoax unraveled. Still, the Cardiff Giant demonstrated how spectacle plus ticket sales can override careful inquiry.

Curators and newspapers learned to insist on provenance and method, not just a good story. When a find appears out of nowhere with immediate commercial framing, your guard should go up.

Ask where, how, and by whom it was found, then look for independent testing. Amazement is fine.

Verification turns amazement into knowledge instead of a costly lesson.

4. The Cottingley Fairies (1917)

In 1917, two cousins in Cottingley, England produced photographs that appeared to show them interacting with fairies. The images, charming and artfully composed, matched popular folklore and wartime longing for wonder.

Interest grew when Arthur Conan Doyle publicly endorsed the photos as credible evidence of unseen realms.

Darkroom techniques were not widely understood, and the photos’ staged elegance convinced many viewers. Critics existed, but the desire for enchantment outweighed doubts about paper cutouts and pinned props.

Magicians and photographers later noted telltale signs of manipulation that experts should have caught earlier.

Decades after the photos spread, the girls admitted they had staged most images with cutouts, though they debated whether any were genuine. By then, the Cottingley Fairies had become a cultural parable about belief, expertise, and wishful thinking.

The lesson holds online today: persuasive visuals are not proof without context and chain of custody. If a photo confirms a beloved story too perfectly, scrutinize lighting, perspective, and artifacts.

Curiosity can coexist with rigor. That balance keeps wonder from becoming a vehicle for self-deception.

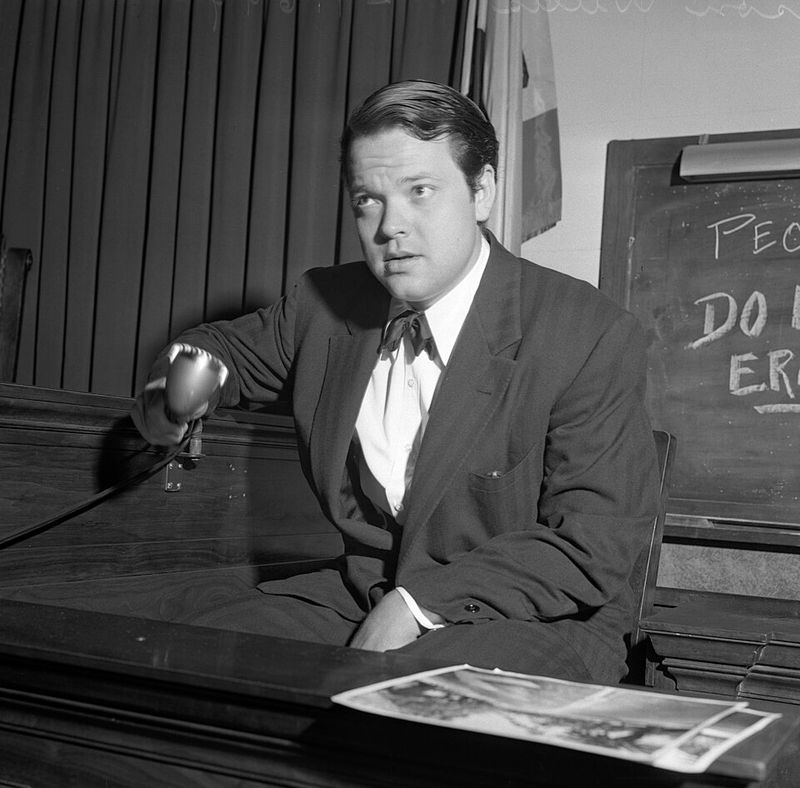

5. The War of the Worlds Panic (1938)

On Halloween eve 1938, Orson Welles aired a radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds using realistic news bulletins. Some listeners tuned in late, missed the disclaimer, and briefly believed Martians had landed in New Jersey.

The broadcast became legendary for supposedly causing nationwide chaos.

Later research shows the panic narrative was largely overstated by rival newspapers criticizing radio. There were confused calls and isolated incidents, but no mass stampedes or broad mayhem.

Still, the show proved how authentic formats can manufacture urgency and uncertainty when context is missed.

The episode influenced media standards for disclaimers, interruptions, and tone during simulated events. It also highlights selective memory: dramatic retellings outlive the quieter facts.

When news bulletins break into entertainment, pause and seek multiple sources before acting. Cross-check station websites, official alerts, and local authorities.

The medium’s style can feel authoritative even when it is fiction. Critical listening is as important as critical reading, especially during fast-moving reports.

6. The Zinoviev Letter (1924)

Days before Britain’s 1924 election, newspapers published a letter allegedly from Soviet official Grigory Zinoviev. It appeared to urge British communists to inflame agitation and influence foreign policy.

The document was treated as authentic and helped damage the Labour government at the polls.

From the start, doubts existed about phrasing, channels, and provenance, but partisanship amplified the story. Intelligence services, private actors, or propagandists may have planted it, and competing inquiries muddied accountability.

The scandal shows how a plausible document, well-timed, can shift political momentum.

Later analyses concluded the letter was a forgery, though its exact authorship remains debated. The case now serves as a template for information operations using leaks and timed releases.

For readers, the takeaway is clear: assess incentives, metadata, and corroboration, not just rhetorical heat. Authentic documents can still mislead if quoted selectively, but forged documents can upend outcomes entirely.

Verification from independent sources and transparent chains of custody are not luxuries during elections. They are essential defenses against manipulation.

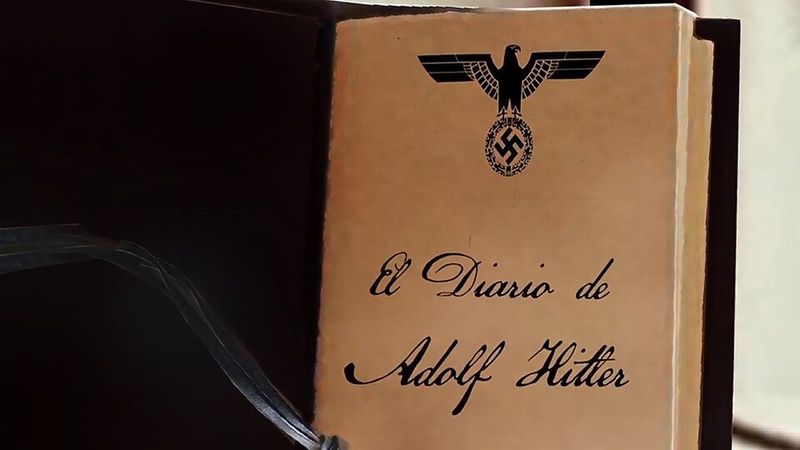

7. The Hitler Diaries (1983)

In 1983, German magazine Stern announced it had acquired Adolf Hitler’s personal diaries. Handwriting experts and historians initially vouched for them, and the scoop promised unprecedented insight into the dictator’s mind.

The international press covered the story intensely, and serialization deals followed.

Very quickly, forensic testing and inconsistencies exposed the truth: the notebooks were modern forgeries by Konrad Kujau. Paper, ink, and binding materials postdated World War II, and internal content recycled known sources.

The incentives of exclusivity, speed, and prestige had outrun careful verification.

The collapse embarrassed publishers and experts, prompting reforms in document authentication. Labs tightened protocols, and editorial standards added phased tests before public claims.

The diaries remind us that authority signals and partial validations can create a false sense of certainty. If a find promises to rewrite history, insist on blind testing, full provenance, and cross-institutional review.

Extraordinary sources deserve extraordinary scrutiny. That mindset protects both the public record and the credibility of those who report it.

8. The Sokal Affair (1996)

In 1996, physicist Alan Sokal submitted a deliberately nonsensical paper to the journal Social Text. The article used dense jargon and fashionable theory to argue that physical reality was a social construct.

The journal published it, unaware it was a test of editorial rigor.

Soon after publication, Sokal revealed the hoax in another magazine, explaining his intent to highlight lax standards and ideological bias. Supporters praised the exposure; critics argued it caricatured the field and misrepresented peer review practices.

The affair sparked broader debate about expertise, interdisciplinarity, and the boundaries of jargon.

The Sokal Affair endures because it shows how style can mask substance, especially when arguments flatter a journal’s perspective. Today, predatory journals and paper mills present related risks, making screening and replication vital.

For readers and students, the lesson is to look for clear claims, methods, and testable predictions. If prose obscures mechanisms and evidence, demand clarification or withhold judgment.

Intellectual humility and methodological transparency remain the surest guides through complex debates.

9. The Great Manure Crisis (1894)

A widely repeated story claims 1890s cities faced an unsolvable horse manure apocalypse that would bury streets under feet of waste. The tale cites a supposed 1894 Times of London prediction and a failed conference that ended early in despair.

In truth, historians find no primary source for the dramatic quotes and timelines.

Urban filth was real, but the extreme doomsday framing appears to be a modern exaggeration that grew online. It compresses complex sanitation history into a neat parable that flatters progress narratives about cars saving cities.

The myth persists because it is tidy, vivid, and easy to share.

Careful research shows multiple solutions emerged over time: better street cleaning, changes in stabling, and gradual transport shifts. Electric trams, bicycles, and later motor vehicles reduced reliance on horses, but there was no single dramatic turning point.

The episode is a meta-hoax, reminding us to check citations, not just vibes. When a historical claim includes precise numbers and tidy endings, ask for scans and archives.

Verification beats virality, especially for stories that confirm modern superiority.

10. The Tasaday Stone Age Tribe (1971)

In 1971, officials in the Philippines introduced the Tasaday as an isolated Stone Age tribe untouched by modern society. Photos and documentaries showed cave living, simple tools, and gentle harmony with the forest.

The story captivated global media and aligned with romantic ideas about noble isolation.

After regime changes, journalists and anthropologists revisited and found signs the narrative was staged or heavily managed. Some Tasaday members reportedly wore modern clothes off camera and had contact with nearby communities.

Political incentives during the Marcos era likely shaped access, presentation, and messaging.

While debates continue about the extent of fabrication, the core claim of pristine isolation did not hold. The case underscores how gatekeeping, staged access, and selective filming can craft persuasive fictions.

Ethical fieldwork requires long-term observation, triangulation with local knowledge, and independent oversight. When an extraordinary anthropological discovery arrives via tightly controlled tours, skepticism is healthy.

Respect for communities and truth both demand careful, transparent methods.

11. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (early 1900s)

Published in the early 1900s, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion claimed to reveal a secret Jewish plot for world domination. Investigations quickly showed it was a plagiarized forgery assembled from earlier political satire and fiction.

Despite exposure, it spread widely and fueled antisemitic propaganda for decades.

The text’s power came from conspiratorial structure and adaptable vagueness, allowing readers to map any event onto its claims. Governments and extremists used it as a propaganda tool, reprinting and translating it for new audiences.

Each crisis became proof, rather than a test, of the document’s false theories.

Responsible scholarship and court rulings in multiple countries dismantled the text’s credibility. Yet the Protocols demonstrate how forgeries can outlive debunkings when they meet ideological needs.

The lesson is stark: evaluate sources, demand provenance, and understand rhetorical tactics. Conspiracy literature rarely invites falsification.

Healthy skepticism pairs with empathy to resist narratives that target whole communities.

12. The Dreadnought Hoax (1910)

In 1910, members of the Bloomsbury Group, including Virginia Woolf, disguised themselves as Abyssinian royalty to tour HMS Dreadnought. Their makeup, costumes, and invented language were convincing enough to secure honors and a formal inspection.

Afterward, newspapers splashed the prank across front pages.

The episode embarrassed the Royal Navy, though no lasting harm occurred. It revealed vulnerabilities in deference to status and uniform, and it showed how ceremonial settings can short-circuit verification.

The pranksters sent thank-you telegrams in mock dialect, deepening the farce.

Retellings sometimes romanticize the hoax, but its best lesson is procedural: trust, but verify, even when guests arrive with apparent credentials. Institutions adapted by tightening identification and interpretation protocols.

Humor can reveal real weaknesses, and this hoax did so vividly. For readers, it is a reminder that authority signals are only as strong as the checks behind them.

Polite skepticism protects both hospitality and security.

13. The False Spanish Prisoner Con (1800s–early 1900s)

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, victims worldwide received letters about a wealthy nobleman secretly imprisoned in Spain. The writer promised a cut of hidden funds if the recipient advanced fees or provided banking help.

The narrative appealed to greed and empathy, creating urgency with confidential tones.

This Spanish Prisoner con is the ancestor of modern advance-fee frauds, including infamous email scams. Scammers tailored details to local contexts, used convincing stationery, and demanded secrecy to prevent verification.

Once fees were sent, more obstacles appeared, each requiring extra payment.

The scheme teaches durable lessons about social engineering. Unsolicited opportunities with outsized rewards deserve deep skepticism.

Independent verification, refusal to rush, and never paying upfront for uncertain promises are practical defenses. Authorities today advise reporting such approaches and using bank-level security practices.

Technology changes delivery methods, but psychological levers stay remarkably stable. Recognizing patterns is your best protection.

14. The BBC Spaghetti Tree Hoax (1957)

On April Fools Day 1957, the BBC aired a Panorama segment showing Swiss families harvesting spaghetti from trees. The calm narration and authoritative presentation made the scene feel plausible to some viewers.

After the broadcast, thousands contacted the network asking how to grow spaghetti at home.

The hoax worked because the format signaled trust and because pasta was less familiar in Britain at the time. The visuals were simple, tidy, and free of overt absurdity, allowing viewers to suspend disbelief.

It became one of television’s classic pranks and a case study in media literacy.

Today, the segment is still replayed as a gentle reminder to question context, especially on reputable platforms. Even trusted institutions occasionally play with expectations.

Before accepting a surprising claim, check the date, seek corroborating sources, and look for expert commentary. Humor has its place, but clarity matters when audiences rely on you for facts.

Responsible skepticism keeps curiosity fun instead of confusing.

15. Balloon Boy (2009)

In 2009, a Colorado family reported that their six-year-old son had floated away in a homemade helium balloon. Live television followed a silver saucer drifting across the sky as officials mobilized for a rescue.

Viewers watched in real time, fearing the worst and hoping for a safe outcome.

Hours later, the child was found hiding at home, and suspicions turned toward staging and media manipulation. Investigators concluded the incident was a hoax aimed at securing publicity.

The parents faced legal consequences, and the episode sparked debate about live coverage and verification.

Balloon Boy showed how breaking news can outpace facts when cameras chase spectacle. Audiences can protect themselves by waiting for confirmations, distinguishing speculation from reporting, and noting on-the-record sources.

Newsrooms have since updated procedures for unfolding events, emphasizing restraint. For you, the takeaway is straightforward: when a story accelerates quickly, slow your conclusions.

Accuracy arrives slower than adrenaline, but it is worth the wait.