Life in medieval times was demanding, relentless, and rarely comfortable. Survival meant navigating hazards that modern people rarely face, from unsafe water to untreatable disease.

This article lays out the everyday realities that shaped work, health, family, and community. Read on for a clear, factual look at what people actually endured.

1. You probably smelled… all the time

Medieval hygiene looked different from today’s expectations. Daily baths were uncommon for most people, and soap was expensive or harsh.

Clothes were washed infrequently, and laundering meant hard labor at streams or communal washhouses that were not always accessible.

Smells layered together. Hearth smoke clung to wool garments, animals lived close to people, and waste disposal systems were crude.

Privies, chamber pots, and open gutters contributed odors that lingered in narrow streets.

People masked smells with herbs, scented waters, or smoking rooms with fragrant woods, but those measures were limited. Guilds like tanners produced powerful stenches near homes and markets.

You would grow accustomed to it, yet visitors from cleaner countryside or different quarters might still notice.

Even wealthier households struggled with ventilation and soot. Perfumes and linen changes helped, but could not erase city funk.

The baseline reality was a mix of sweat, smoke, animals, and refuse that followed you everywhere.

2. Clean drinking water wasn’t guaranteed

Access to safe water was inconsistent. Wells could be shallow or poorly lined, letting runoff leak in.

Rivers and streams doubled as washing sites and waste channels, so contamination was common even when water looked clear.

People often drank small beer or weak ale because the brewing process involved boiling, which reduced pathogens. Alewives were important providers, and households brewed at home.

That did not mean perfect safety, but it was frequently safer than raw water.

Urban centers developed conduits and regulated sources in some regions, yet maintenance and enforcement varied. Droughts or floods quickly compromised supplies.

In villages, the nearest source might be shared with animals, increasing risk.

Travelers and the poor had the fewest options. If you were thirsty, you balanced convenience against illness.

Boiling, filtering through cloth, and mixing with ale or wine were practical strategies used when possible.

3. You could die from a small cut

Without antibiotics, minor wounds could become deadly. A cut from a tool or thorn could introduce bacteria, leading to infection and sepsis.

Work environments were dirty, and protective gloves or disinfectants did not exist for ordinary laborers.

Treatments varied. People used herbal salves, honey, vinegar, and poultices, sometimes with real antiseptic effects.

But improper care, contaminated bandages, or delayed attention could let infection spread.

Blood poisoning was not understood scientifically. Healers watched for redness, swelling, heat, and fever, yet remedies were inconsistent.

If the infection reached the bloodstream, rapid decline followed.

Amputation to stop gangrene was a last resort with high risk. Pain control was minimal, and surgical tools were crude by modern standards.

A small accident in a field or workshop could turn into a life-threatening crisis within days.

4. Tooth problems were a lifelong nightmare

Dental care was rudimentary. Diets rich in coarse bread and grit from millstones wore enamel, while sweets, when available, promoted decay.

Toothaches, abscesses, and gum disease were common companions from youth to old age.

Remedies ranged from herbal rinses to charms. When extraction became necessary, barber-surgeons pulled teeth with forceps or a dental key, often without effective anesthesia.

Infection and broken roots made outcomes unpredictable.

Replacement options were limited. Some cultures tried bone or wooden implants, but medieval Europe mostly relied on gaps or crude dentures.

Social appearance mattered, yet pain relief took priority over aesthetics.

Cleanliness varied by region and status. Chewing sticks, cloth rubs with salt, and wine rinses helped some people.

Still, chronic pain, foul breath, and dangerous infections made every meal and cold night a potential ordeal.

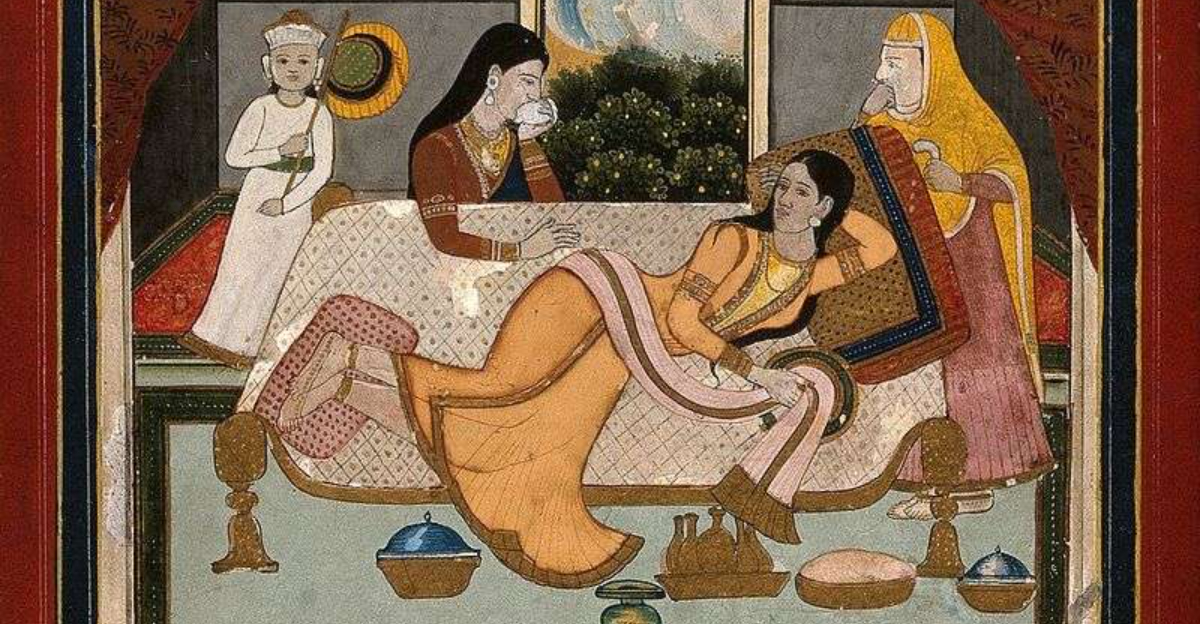

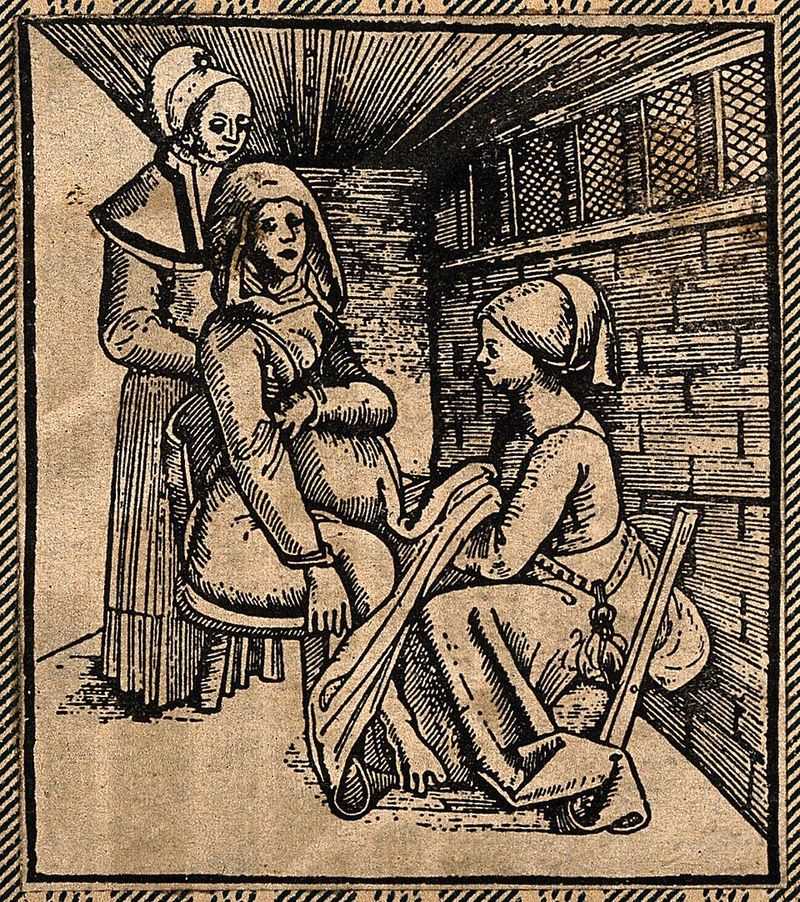

5. Childbirth was genuinely deadly

Pregnancy and childbirth carried serious risks for mothers and infants. Hemorrhage, obstructed labor, puerperal fever, and eclampsia were poorly understood and hard to treat.

Even wealthy households with attendants and heated rooms could not avoid danger.

Midwives provided valuable experience, using position changes, massage, and herbal aids. But without sterile technique or surgical options like safe cesareans, complications escalated quickly.

If fever followed delivery, mortality rose sharply.

Many women gave birth multiple times, increasing cumulative risk. Nutritional stress, infections, and limited recovery windows compounded hazards.

Surviving childbirth did not guarantee long-term health, as pelvic injuries and chronic pain were common.

Communities supported new mothers with churching rituals and practical help. Still, every labor involved uncertainty.

In a world without modern obstetrics, even routine deliveries required courage and luck.

6. Infant mortality was heartbreaking

Many children did not survive early childhood. Premature birth, infections, diarrhea, and respiratory illness were common killers.

Without vaccines or antibiotics, small setbacks became fatal.

Breastfeeding improved survival, but maternal health and food scarcity affected milk supply. Weaning introduced contaminated foods and water, raising risk of disease.

Families sometimes baptized newborns quickly due to fear of early death.

Communities created customs to cope with loss, from naming practices to memorial rites. Parents loved their children, despite the risk of grief.

Household economies also relied on multiple offspring to offset mortality and labor needs.

Improved odds came with better sanitation, stable food, and wealth, yet no group was immune. Court records and parish registers reveal frequent burials of the very young.

The emotional and practical toll shaped family life at every stage.

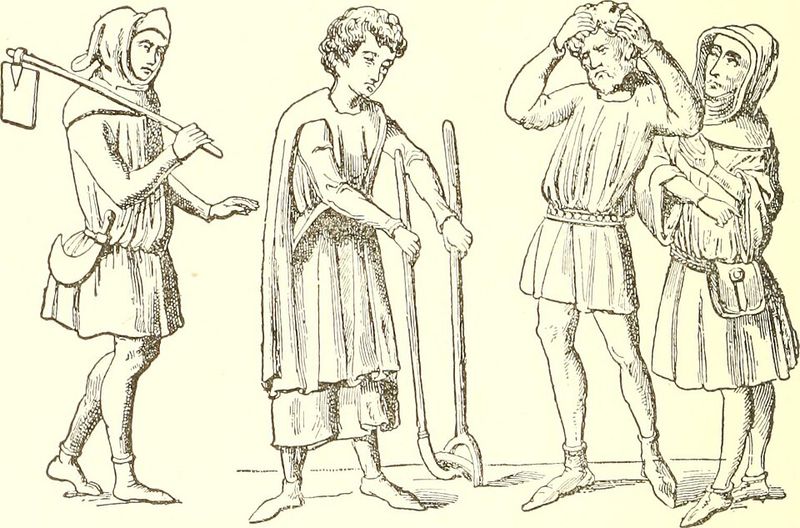

7. Most people worked from sunrise to sunset

For peasants and artisans, work filled nearly every daylight hour. Fields needed plowing, sowing, weeding, and harvesting across the seasons.

Tasks like spinning, mending, and tool repair filled evenings.

There were saints’ days and festivals, but they did not resemble modern weekends. Obligations to lords or manors demanded corvée labor, rents, and dues.

Missing work risked penalties or lost food.

Tools reduced some strain, yet muscle powered most jobs. Weather dictated schedules, and bad seasons meant longer days for smaller yields.

Children joined chores early, learning skills essential for survival.

Craft guilds maintained standards and apprenticeships in towns, but hours were still long. Candlelight extended productivity when necessary.

Work-life balance, as a concept, had little room in subsistence economies.

8. Winter wasn’t cozy – it was terrifying

Winter strained households. Fires were small to conserve fuel, and smoke often leaked into rooms.

Poor insulation meant drafts cut through timber and thatch, chilling people even beside the hearth.

Food stores determined survival. If the harvest failed, granaries ran low by late winter.

Illness like influenza and pneumonia took hold when bodies were underfed and crowded indoors.

Travel was dangerous on icy, muddy roads. Markets shrank, prices rose, and relief options were limited.

Animals needed fodder, competing with human needs for scarce resources.

Communities shared when they could, but hunger and cold narrowed margins. Clothing layers helped, yet damp wool never felt warm for long.

Winter was a test of planning, luck, and the strength of neighbors.

9. Food shortages could happen anytime

A single bad harvest tightened belts. Two bad seasons in a row could push communities toward famine.

Weather, pests, or war disrupted planting and transport, leaving markets thin and prices high.

Households stretched supplies with barley, rye, and peas. Foraging, fishing, and preserving offered buffers, but not guarantees.

Lords sometimes released reserves, and churches organized alms, though relief rarely met need.

Malnutrition weakened bodies, inviting disease. Children and the elderly suffered first.

Desperate measures like eating seed grain jeopardized the next year’s prospects.

Records from the Great Famine of the early 14th century illustrate the pattern. Hunger lasted months, not days, and recovery took years.

In such cycles, planning mattered, yet chance still ruled outcomes.

10. Your diet was boring and repetitive

Most people ate variations of bread, pottage, and legumes. Seasonal vegetables rounded out meals, with herbs for flavor when available.

Meat appeared rarely for peasants, more often as salted or smoked bits rather than fresh roasts.

Monotony came from necessity. Grain harvests set the menu, and pottage simmered daily with whatever the garden or market allowed.

Dairy played a role when herds were healthy, offering cheese and whey.

Feast days brought variety, but not every table shared equally. Spices were costly imports, reserved for the wealthy.

Even they relied on preserved foods through winter.

Nutrition depended on luck and labor. A steady but plain diet kept people going, though deficiencies were common in lean years.

You would know every shade of barley, rye, and pea far more than exotic flavors.

11. Life was ruled by disease

Epidemics shaped communities. Plague waves, smallpox, dysentery, and typhus struck at intervals, moving along trade routes and crowded streets.

People recognized patterns of contagion without grasping microbes.

The Black Death of the mid 14th century killed a vast share of Europe’s population. Towns lost workers, families, and knowledge quickly.

Aftershocks lasted decades, changing wages, land use, and social relations.

Daily life involved coping strategies. Quarantines, flight, and prayer were common responses.

Healers offered mixtures and procedures with mixed results.

Sanitation improvements came slowly, and cramped housing kept illness circulating. Even when disease faded, fear of its return persisted.

Health, like harvests, felt subject to forces beyond control.

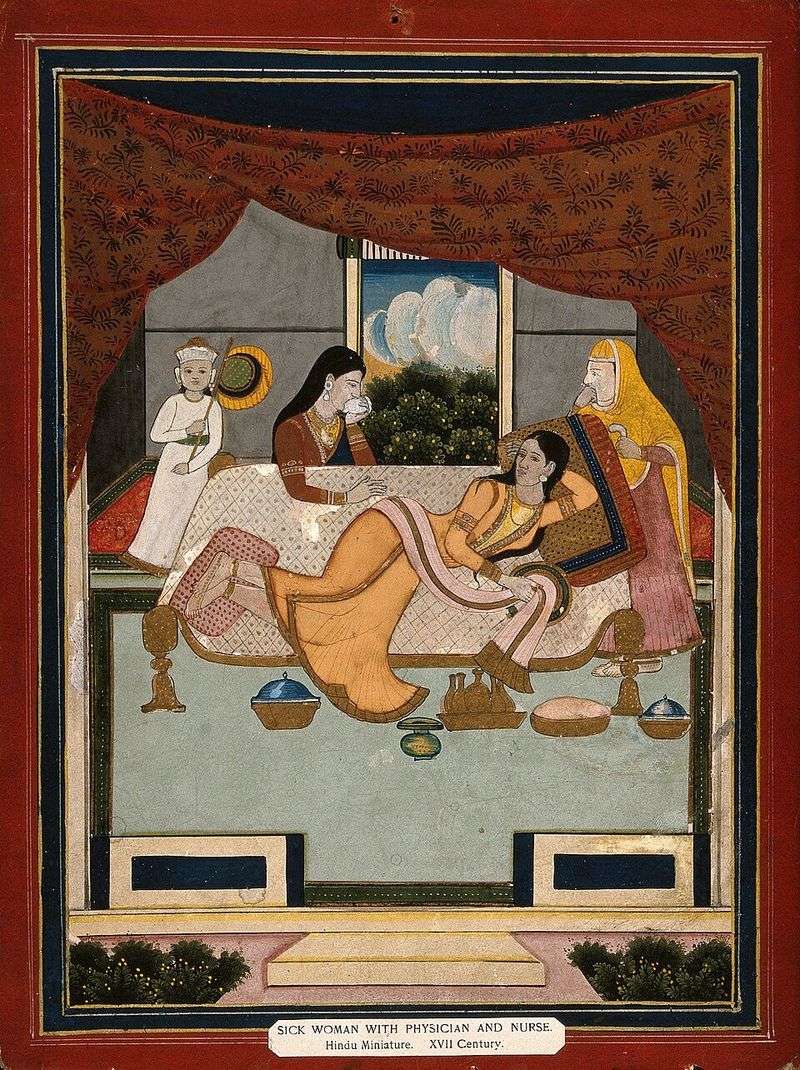

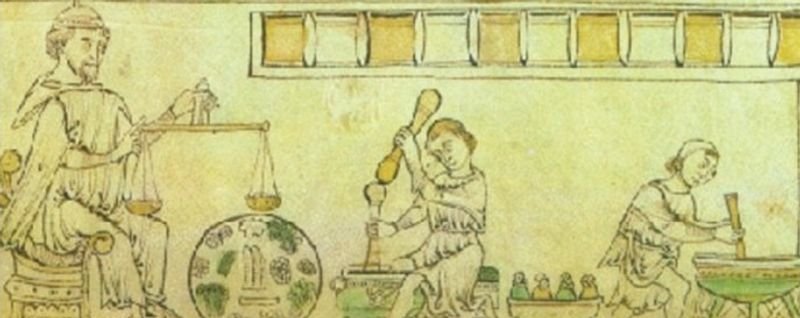

12. Medicine was a mix of superstition and luck

Medical practice blended observation, tradition, and belief. Humoral theory guided diagnoses, aiming to balance blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile.

Treatments included purges, bloodletting, cupping, and complex herbal recipes.

Some remedies helped, like willow bark for pain or honey for wounds. Others harmed or delayed proper care.

Astrology and religious ritual often framed timing and choice of treatments.

Training varied widely. University-educated physicians served elites, while barber-surgeons and midwives handled most practical care.

Folk healers remained important where formal services were scarce.

Outcomes depended on the illness, the healer’s skill, and chance. Without germ theory or sterile technique, infections spread easily.

People did what they could with the knowledge and materials they had.

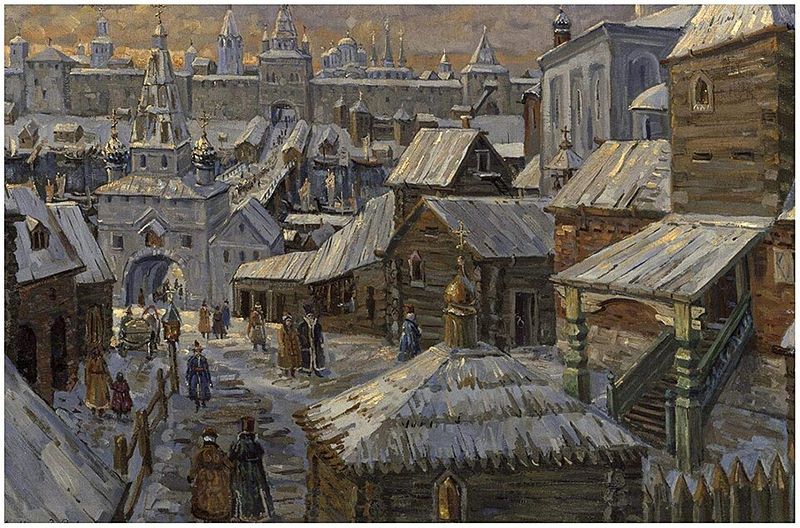

13. Cities were filthy

Urban growth outpaced sanitation. Narrow lanes funneled waste, and gutters carried sludge through markets.

Residents tossed refuse and chamber pot contents into streets, despite periodic regulations.

Animals shared space with people. Pigs rooted in garbage, horses dropped manure, and rats thrived in grain stores.

Water sources near tanneries or butchers absorbed runoff, compounding smells and hazards.

Authorities passed ordinances to clean streets or confine animals, but enforcement was uneven. Guilds and neighborhoods organized sweeps before festivals.

Still, daily mess accumulated faster than crews could remove it.

Filth was not constant everywhere, yet even better districts struggled after heavy rain. Mud, waste, and traffic turned thoroughfares into hazards.

Living in a city meant opportunity, noise, and a constant battle against grime.

14. Fire could wipe out your whole town

Construction favored timber frames and thatch, stacked close along narrow streets. A single spark from a hearth or workshop could ignite a row in minutes.

Without modern pumps, firefighting relied on buckets, hooks, and sheer effort.

Authorities set curfews for forges and ovens, and some towns mandated tile or plaster in higher risk zones. Even so, wind turned embers into walls of flame.

Insurance and rebuilding funds were limited or informal.

Households stored fuel and hay near heat sources for convenience. That practical choice increased danger.

Neighbors depended on each other to form lines and tear down roofs to make firebreaks.

Afterward, families faced homelessness and lost tools. Rebuilding took seasons, not weeks.

Fire safety shaped daily habits, from banked coals to guarded candles.

15. You had almost no personal freedom

Birth largely fixed your status. Serfs owed labor, rents, and fees to lords, and movement off the manor required permission.

Opportunities for social mobility existed but were narrow and risky.

Town life offered guild membership for some, yet entry required sponsorship, fees, and years of apprenticeship. Marriage choices, property rights, and inheritance followed local custom and law, limiting autonomy.

Taxes and tithes layered on top of obligations. Justice systems favored elites, and appeals were costly.

Even personal time bent to agricultural cycles and communal requirements.

Freedom varied by region and era, improving after crises like the Black Death in some places. Still, most people stayed close to where they were born.

Choices were framed by duty, necessity, and survival.

16. You could be punished brutally for small crimes

Justice was swift and public. Theft or repeat offenses might mean whipping, branding, mutilation, or execution.

Lesser crimes earned time in the stocks or pillory, inviting ridicule and thrown refuse.

Punishments aimed to deter and display authority. Trials weighed oaths, local testimony, and custom more than forensic evidence.

Fines hit hard in communities living close to the margin.

Clerical courts handled some cases differently, yet penalties still stung. Nobles frequently received leniency compared to commoners.

Traveling judges imposed order during assizes, leaving lasting impressions.

Community expectations mattered as much as statutes. Reputation could save or doom you.

A misstep that seems minor today could cost you a hand, a brand, or your life.

17. War wasn’t heroic – it was horror

Conflict disrupted every layer of life. Raids burned crops, seized livestock, and scattered families.

Sieges trapped civilians behind walls, where hunger and disease spread faster than arrows.

Armies lived off the land, often at locals’ expense. Ransom, plunder, and forced labor followed campaigns.

Even victors limped home with wounds that healers could not reliably treat.

Chronic warfare eroded trust and trade. Merchants avoided routes, and villages rebuilt the same barns repeatedly.

Survivors measured time by disasters rather than harvests.

Chivalric ideals existed, but they did not protect most people. For ordinary households, war meant loss, fear, and years of recovery.

Heroism was survival under relentless pressure.

18. Religion controlled everyday life

The church shaped work rhythms and community events. Feast days, fasts, and saints’ calendars structured the year.

Tithes supported clergy and charity, while rituals marked birth, marriage, and death.

Moral teaching influenced behavior and law. Courts addressed marriage, oaths, and inheritance with religious framing.

People sought guidance through confession, pilgrimage, and prayer.

Belief coexisted with practical needs. Farmers watched the weather and consulted almanacs while honoring holy days.

Skepticism and dissent appeared, but social pressure favored conformity.

Religious art, music, and festivals tied villages together. At the same time, obligations consumed time and resources.

Faith offered meaning, but also rules that reached into daily choices.

19. Privacy barely existed

Space was shared. Many peasant homes were single rooms where cooking, sleeping, and work intertwined.

Families slept close to conserve warmth, sometimes near animals kept indoors for security and heat.

Even wealthier households buzzed with servants, apprentices, and guests. Doors opened frequently, and thin walls carried sound.

Letters and locks were rarer, so conversations were public by default.

Bathing and toileting offered little seclusion. Screens and corners stood in for private rooms.

Community life valued cooperation over solitude.

When quiet was needed, people walked fields or visited chapels. Still, constant company shaped habits and expectations.

Privacy, as a modern ideal, was a luxury few could afford.

20. Entertainment was limited (and often violent)

Leisure fitted around work and church calendars. Festivals brought music, dancing, and games, offering rare breaks from routine.

Storytelling, dice, and board games filled evenings by the hearth.

Rougher spectacles drew crowds. Animal baiting, public punishments, and tournaments mixed danger with spectacle.

Ethics differed, and many events doubled as marketplaces and social hubs.

Guild feasts and seasonal rites blended food, drink, and performance. Traveling performers carried news and novelty between towns.

Books entertained the literate few, usually in monasteries or elite homes.

Most days repeated familiar tasks. When entertainment arrived, it was communal and often physical.

Amusement reflected the era’s values, resources, and tolerance for risk.