American television didn’t drift into diversity by accident. It changed because certain people refused to stay in the background.

In those early days, Black performers were battling more than nerves. Sponsors hesitated.

Networks doubted. Audiences watched with a kind of uncertainty that could turn cold fast.

Still, they showed up. Again and again.

Not to make a point, but to do the work, deliver the laugh, land the line, and claim space.

If you’ve ever wondered how “normal” TV became, it starts here.

Ethel Waters: The First Face on the Small Screen

Before most Americans even owned a television set, Waters was already making history on one. June 14, 1939, might not ring any bells for you, but that’s the day she hosted an NBC variety special that historians now recognize as the first TV show hosted by a Black performer.

Television itself was basically a newborn baby at that point.

Waters had already conquered Broadway and Hollywood by then, but this was different. Radio couldn’t show your face.

Movies played in segregated theaters. Television came right into people’s homes, whether they were ready for it or not.

The show lasted just one hour, and few recordings exist today. But Waters proved something crucial in that single broadcast.

Black entertainers could command a screen, hold an audience, and deliver exactly what this new medium needed. She opened a door that many others would walk through, even though Hollywood kept trying to nail it shut.

Her pioneering moment came so early that most of the country couldn’t even watch it. Television sets were rare, expensive, and mostly concentrated in New York.

Still, the precedent was set, and there was no taking it back.

Hazel Scott: The Woman Who Made It a Series

Scott didn’t just appear on television. She got her own show, her own timeslot, her own name in the title.

The Hazel Scott Show premiered in 1950 on the DuMont network, making her the first Black American to host an entire TV series. The show featured her incredible piano skills, and for a brief moment, it looked like the door was swinging wide open.

Then the Red Scare happened. Scott found herself blacklisted after appearing before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Her show was cancelled after just three months, and her career took a devastating hit. The door slammed shut again, but the hinges were permanently loosened.

What Scott accomplished in those few months mattered more than the length of the run. She proved that a Black woman could carry a show, attract sponsors, and deliver quality entertainment week after week.

Networks couldn’t pretend it was impossible anymore.

Her show may have been short-lived, but the breakthrough was permanent. Every Black woman who has hosted a TV show since owes something to Hazel Scott’s courage and talent during those turbulent times.

Nat King Cole: The Ratings Hit Nobody Would Sponsor

Cole’s voice could sell millions of records, but apparently it couldn’t sell soap. The Nat King Cole Show launched on NBC in 1956 as the first nationally broadcast TV show hosted by an African American.

It was good, too. Critics loved it.

Viewers tuned in. Everything looked perfect except for one massive problem.

No major sponsors would touch it. Southern affiliates threatened to drop the show.

Advertising agencies claimed their clients wouldn’t associate their products with a Black host, no matter how talented or famous. Cole kept the show going for over a year, but the financial reality became impossible to ignore.

The whole situation exposed exactly how racism worked in the business. Cole wasn’t failing.

The system was failing him on purpose. He was too successful, too polished, too undeniable for the usual excuses, so the industry found new ways to keep the door from opening too wide.

When the show finally ended in 1957, Cole was bitter but unbowed. He’d proven that Black entertainers could host national television shows and deliver quality programming.

The sponsors would eventually come around, but it would take another decade and a lot more pioneers.

Gail Fisher: The Emmy That Changed Everything

Fisher played Peggy Fair on Mannix, and she was so good at it that the Television Academy couldn’t ignore her. In 1970, she won the Emmy for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series.

History books often credit her as the first African American woman to win an Emmy for acting, and that recognition opened doors that had been welded shut.

Her character wasn’t a maid or a stereotype. Peggy Fair was a secretary, a professional, a widow raising a son.

She was smart, capable, and essential to the show’s success. Fisher played her with dignity and warmth, creating a character that audiences of all backgrounds could respect.

The Emmy win validated what Black actresses had been saying for years. They could carry dramatic roles.

They could win awards. They could be leading ladies, not just supporting players.

Fisher proved it on one of television’s biggest stages.

Her career faced challenges after Mannix ended, but her impact remained. Every Black actress who has won an Emmy since stands on the foundation Fisher built.

She showed the industry and the world that excellence couldn’t be denied forever, even when the system tried its hardest.

Diahann Carroll: The Nurse Who Wasn’t a Stereotype

Carroll walked into television history when Julia premiered on NBC in 1968. She played Julia Baker, a widowed nurse raising her son.

Simple premise, revolutionary execution. This was the first U.S.

TV series to star a Black woman in the lead role, and Julia Baker wasn’t cleaning anyone’s house or serving anyone’s dinner.

The show drew criticism from multiple directions. Some felt it was too safe, too sanitized, not representative of the Black experience during the Civil Rights era.

Others objected to seeing a Black woman in a professional role at all. Carroll navigated the controversy with grace while delivering performances that earned her a Golden Globe and four Emmy nominations.

Julia ran for three seasons and proved that audiences would tune in to watch a Black woman lead a primetime series. The ratings backed up what Carroll already knew.

Representation mattered, and people were hungry for it.

Not every episode was perfect, and the show’s politics remain debated today. But Carroll’s achievement stands untouched.

She was the first, and being first is never easy. She carried the weight of expectation and delivered excellence anyway, changing television in the process.

Nichelle Nichols: The Lieutenant Who Kissed a Captain

Lt. Uhura sat at the communications console of the USS Enterprise, and suddenly the future looked different.

Nichols played one of the first Black women in a major primetime role, and she did it on a show about exploring strange new worlds. The symbolism wasn’t subtle, and it didn’t need to be.

Then came the kiss. In 1968, Nichols and William Shatner shared what’s frequently cited as television’s first interracial kiss.

Some stations refused to air it. Some viewers were outraged.

Many more viewers saw it as progress, proof that television could reflect a changing America.

Nichols almost left the show after the first season, but Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. personally convinced her to stay. He told her that her role mattered, that representation mattered, that Black children needed to see her on that bridge every week.

She listened, and she stayed.

Her impact extended beyond the screen. NASA recruited her to help diversify the astronaut program, and she brought in candidates including Sally Ride and Guion Bluford.

Nichols proved that television pioneers could change more than just TV. They could change the world.

Esther Rolle: The Mother Who Refused to Play the Fool

Rolle created Florida Evans on Maude, then carried the character to Good Times, where she became the heart of one of television’s first Black family sitcoms. She played Florida with warmth, strength, and dignity.

Then the show started changing, and Rolle started fighting back.

The producers increasingly focused on J.J., played by Jimmie Walker, and his catchphrase-spouting antics. Rolle and John Amos objected publicly, arguing that the show was drifting into caricature and undermining its original purpose.

When their concerns were ignored, both actors eventually left the show in protest.

Rolle’s willingness to walk away from a hit show demonstrated something crucial. Black actors didn’t have to accept whatever roles they were given.

They could demand better, fight for dignity, and refuse to participate in their own stereotyping. The cost was real, but so was the principle.

She returned to Good Times for its final season after some changes were made, but the damage was done. Still, Rolle’s stand mattered.

She showed that pioneers don’t just open doors. Sometimes they have to guard those doors and fight to keep them from swinging backward into harmful territory.

Isabel Sanford: The Maid Who Became the Leading Lady

Sanford started as the maid on All in the Family, but she didn’t stay there. When The Jeffersons premiered in 1975, she moved on up as Louise Jefferson, and television got one of its greatest characters.

Louise was sharp, funny, grounded, and absolutely essential to the show’s success.

In 1981, Sanford won the Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series. Britannica credits her as the first Black actress to win an Emmy for a lead role.

The significance of that win extended far beyond one trophy. It validated Black actresses in leading roles and proved that they could carry sitcoms to critical and commercial success.

The Jeffersons ran for eleven seasons, making it one of the longest-running sitcoms with a predominantly Black cast. Sanford anchored the show through every episode, creating a character that audiences loved and respected.

Louise Jefferson wasn’t a stereotype. She was a fully realized person.

Sanford’s career path told its own story. She went from playing maids to playing a wealthy woman with a maid of her own.

That journey reflected the possibilities that television pioneers were creating, not just for themselves but for everyone who came after.

Al Freeman Jr.: The Daytime Drama Breaker

Soap operas weren’t exactly known for their diversity, but Freeman changed that conversation. He played Ed Hall on One Life to Live, and in 1979, he won the Daytime Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actor.

History credits him as the first African American actor to earn that lead-actor Daytime Emmy, breaking ground in a genre that had largely ignored Black performers.

Daytime television reached millions of viewers, mostly women watching at home. Freeman’s presence in a leading role normalized Black characters in ways that primetime couldn’t always match.

His character dealt with real issues, had real relationships, and existed as a full person rather than a token.

The Emmy win validated Freeman’s work and opened doors for other Black actors in daytime drama. Soap operas began slowly diversifying their casts, adding Black characters with substantial storylines rather than brief appearances.

The change was gradual, but Freeman’s breakthrough made it possible.

He continued working in television and film for decades, but that Daytime Emmy remained a landmark achievement. Freeman proved that Black actors could excel in every television genre, not just the ones that networks traditionally allowed them to enter.

Every door was worth kicking open, even the ones leading to fictional towns and dramatic storylines.

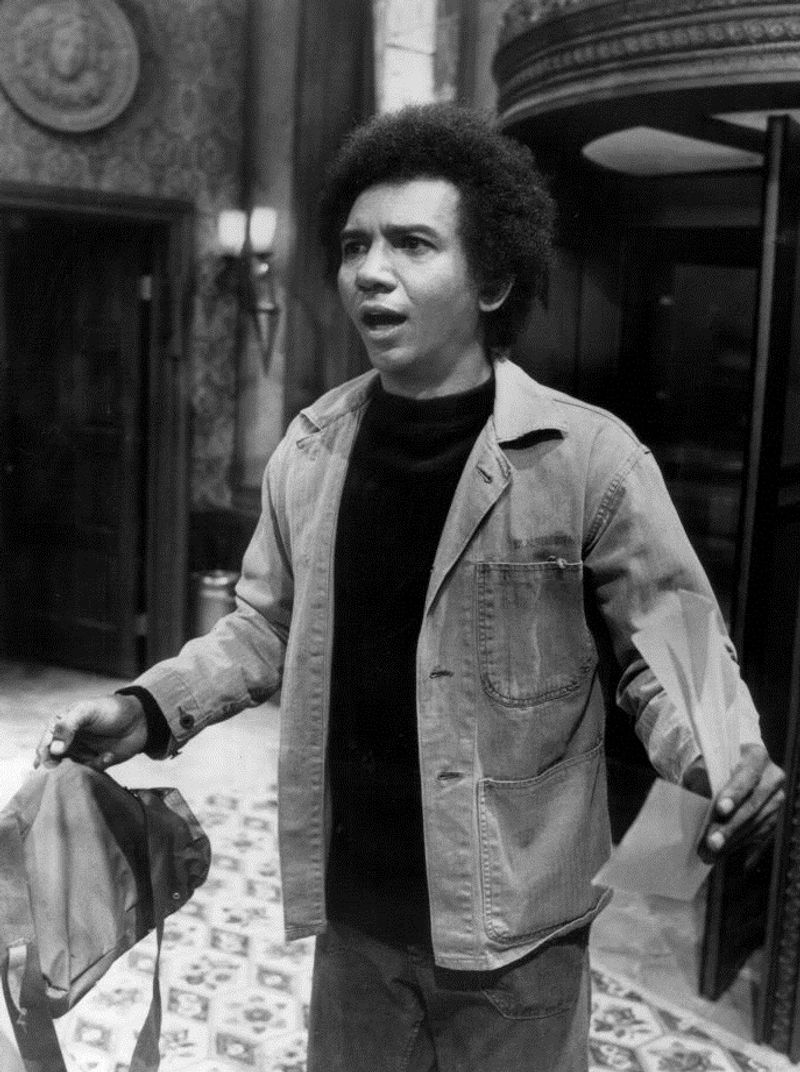

Flip Wilson: The Comedian Who Made Them Laugh and Think

Wilson’s variety show became a phenomenon. The Flip Wilson Show launched in 1970 and quickly climbed to No. 2 in the Nielsen ratings.

Britannica notes it was one of the first TV shows hosted by an African American to become a genuine ratings success. Wilson made it look easy, but nothing about his achievement was simple.

His comedy was sharp, his characters were memorable, and his show welcomed guests of all backgrounds. Geraldine Jones became a cultural icon.

The show won Emmy awards and proved that a Black comedian could command Thursday night television and win over mainstream America without compromising his identity.

Wilson’s success mattered because it was undeniable. Networks couldn’t claim that Black hosts couldn’t attract audiences.

Sponsors couldn’t claim that advertisers wouldn’t support Black-led shows. Wilson demolished those excuses with ratings that spoke louder than any argument.

The show ran for four seasons, and Wilson walked away on his own terms. He’d proven what needed proving and opened doors that would stay open.

His influence extended beyond comedy into the broader conversation about who deserved space on television and who got to make America laugh.

Don Cornelius: The Train That Changed the Sound of TV

Cornelius created something that had never existed before. Soul Train launched in 1971 as the first TV music-variety show to prominently feature African American acts and dancers.

Britannica describes how it ran nationally for decades, reshaping what mainstream television looked and sounded like. The show became an institution.

Every Saturday morning, Soul Train brought Black music, Black fashion, and Black culture into homes across America. The dancers became stars.

The Soul Train line became iconic. Cornelius hosted with smooth authority, introducing acts that ranged from James Brown to Destiny’s Child over the show’s incredible run.

The show’s impact extended far beyond entertainment. Soul Train documented Black culture during crucial decades of change and growth.

It preserved performances, launched careers, and created a visual archive of how Black America moved, dressed, and expressed itself through music.

Cornelius remained involved with the show until 2006, an astonishing 35-year run. Soul Train proved that Black-created, Black-focused programming could thrive for generations.

The show’s success demolished the notion that Black content only appealed to Black audiences. Everyone wanted a ticket on that train.

Bryant Gumbel: The Morning Face That Changed the News

Morning television had a certain look for decades, and that look was white. Gumbel changed it when he became principal anchor of NBC’s Today on September 27, 1982.

This was major network morning news, watched by millions of Americans starting their day. Gumbel’s presence in that chair represented a massive milestone for Black representation.

He held the position for 15 years, becoming one of the most recognizable faces in television news. Gumbel interviewed presidents, covered major stories, and proved that a Black journalist could command the morning news landscape with authority and skill.

His tenure normalized Black anchors in ways that opened countless doors.

The significance went beyond one man’s success. Gumbel’s presence told Black children that they could aspire to network news anchor positions.

It told America that Black journalists deserved the biggest platforms. It changed expectations about who got to deliver the news and whose voice carried authority.

Gumbel eventually moved to other projects, including HBO’s Real Sports, but his Today show years remain landmark television. He was the first Black principal anchor of a major network morning show, and that achievement changed American television permanently.