The first clue you are close is the scent of salt and lilacs drifting up from the Straits, then the sudden sweep of the world’s longest porch at Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island. Inside, a dining room glows under chandeliers while a carving cart rolls past like a promise you can smell before you see it.

Tonight’s prize is prime rib done with ceremony, and the island insists you earn it without cars, just hoofbeats and waves. White columns frame the bluff, horse-drawn carriages clip along below, and every detail feels tuned to another century.

Keep reading, because the ritual here turns dinner into a memory you can taste for years.

The Arrival: Hoofbeats, Harbor Light, Anticipation

The approach begins on the ferry, wind snapping at your jacket while gulls arc over the hull like punctuation. Mackinac’s clapboard storefronts slide into view, then the white facade of the Grand crowns the bluff, a measured exhale above the trees.

No engines wait for you here, only horses and carriages and the sound of hooves ticking against stone like a pocket watch.

The climb is slow in the best way. You notice flowerbeds clipped with old world precision, the porch stretching beside the slope like a bright ribbon.

Lanterns flare as the light thins, and your driver mentions tonight’s roast as if it is weather everyone understands.

Inside the lobby, color floods the senses, Dorothy Draper flourishes turning tradition into theater. The air smells of polished wood and a whisper of perfume from passing gowns.

You follow that scent to the dining room where a silver cart idles, and the first slice of prime rib answers the day’s travel with a soft, pink yes.

The Porch That Teases Dinner

The porch runs like a bright runway along the bluff, white columns marching toward the horizon. Flags riffle, and the Straits breathe in long silver bands, freighters sliding past like patient whales.

Rocking chairs creak with a tempo that urges conversation but saves the best words for later.

Here, anticipation gathers. A violin floats up from somewhere inside, and servers in crisp jackets pass with trays that smell of thyme and warm beef stock.

You can feel the dining room pulling you, not bossy, just certain.

People dress the part because the porch suggests theater. Hemlines swish, cufflinks catch sunset, and the hotel’s green floorboards keep time underfoot.

When the dinner bell rings, it is less sound than gravity, and you set your chair to still, stand, and follow the tide of hunger through those tall doors.

Prime Rib, Carved With Ceremony

The carving cart arrives on quiet wheels, silver reflecting chandelier light in trembling ovals. The lid lifts and a breath of rosemary and beef fat escapes, warm as a hearth.

The prime rib shows a rosy center shaded to mahogany edges, marbled ribbons melting into a soft gloss.

The carver asks your preference like a confidant. End cut for bark and bravado or center slice for velvet surrender.

A ladle of jus lands with a low drum against the porcelain, followed by a disciplined spoon of horseradish that wakes every nerve but never shouts.

First bite, and the blade is irrelevant. Fibers yield with a sigh, salt mapping the road for rendered fat to travel.

You count time in chews, in the hush between table talk, in the way laughter returns wider than before. When the cart glides away, the plate remains a small eclipse of heat and savor, proof that restraint and patience still win the night.

What To Order Around The Roast

Build the plate like a map. Ask for Yorkshire pudding if it is running, a golden bowl for catching jus.

Potatoes whipped to satin do quiet work, while haricots verts snap with a bright, grassy truth.

Glazed carrots shine under a breath of orange, and creamed spinach adds a low, pastoral chord. Order a glass of Michigan cab franc or a Bordeaux blend from the list, something that respects fat and salt without bulldozing the conversation.

If you favor bite, choose the stronger horseradish and let it bloom, then cool it with a forkful of potatoes.

Dessert will call, but leave room for the last ribbon of rib near the fat cap, the piece that holds the evening’s thesis. It tastes of fireplaces and linen, of rituals kept even when no one is watching.

When the plate is clean, the napkin feels lighter, as if starch remembered to be soft again.

The Soundtrack: Pianos, Silver, Soft Shoes

Music does not dominate here. It threads the room like a silk tie, a pianist touching themes you half recall from old records and late movies.

Silver meets china with a light metronome, and shoes murmur across carpet woven in fearless patterns.

This soundscape changes how you chew. You pace bites to the rubato, lift the glass as a phrase resolves, and find that conversation lands as gently as a napkin.

It is not hush for hush’s sake, just a practiced civility that steadies appetite.

When the cart’s wheels whisper by, the piano leans back to let aroma take the solo. Even the servers move musically, gestures edited to essentials.

You notice because the prime rib asks you to, the way good music asks you to notice breath between notes.

Dress Code That Elevates The Bite

After 6, jackets appear and the room sharpens into focus. Not stiff, just intentional, the way a good knife makes tomatoes easier to love.

You feel posture improve as you tie a bow or smooth a sleeve, and suddenly the plate seems larger, more deserving of attention.

There is relief in a rule that flatters everyone. Polished shoes, a real collar, fabrics that sound like whispers when you sit.

The prime rib benefits from this theater, because ritual tunes the palate more than spice ever could.

If you forgot a tie, the front desk will solve it with a smile that suggests this has happened since 1887. Lean in.

The small effort pays back in flavor, and you exit the meal taller, as if the jacket borrowed a bit of the hotel’s backbone.

History On The Plate

The Grand opened in 1887 to welcome rail and steamship travelers seeking lake breezes and long afternoons. Dinner was always a pledge here, multiple courses served with a cadence that kept time with the porch’s shadows.

Prime rib arrived later as American taste leaned toward roast beef Sundays, and the hotel folded it into tradition without breaking rhythm.

Nearby, the Straits once carried timber and iron and now carry tourists and freighters under the Mackinac Bridge’s arc. According to the Mackinac State Historic Parks, the island draws hundreds of thousands each season, and demand for reservations spikes on peak weekends.

The dining room answers with consistency rather than gimmick.

When the carver sets steel to roast, it feels like a page turned with clean fingers. You taste heritage in the restraint: salt, heat, time.

The modern world can scroll all it wants; here, dinner refuses to hurry and somehow still finishes exactly when it should.

Timing The Evening For Maximum Flavor

Book the early seating if you crave sunset through stemware, late if you want a quieter room and a longer glide between courses. Arrive ten minutes before, because the walk from porch to table always takes longer than you think.

Hunger needs room to stretch.

If you are island day tripping, aim for a midweek reservation when ferry crowds thin. Afternoon bikes, a shower, then jacket, then roast.

Ask for a table near the windows if you enjoy silhouettes of passing freighters, though center room tables hear the piano best.

Prime rib rewards calm. Let the slice rest on the plate for a minute while you taste the jus alone, then return with fork and knife.

It is a small patience that turns dinner into remembering.

Conversations You Overhear, And Why They Matter

At the next table, a couple debates end cut versus center like it is baseball strategy, friendly, exact, seasonal. Across the aisle, grandparents tell a teenager about summers before phones, pointing with knife tips at the porch as if it is proof.

The server nods, unhurried, her notes tidy as architecture.

These snatches of talk are seasoning. They color the beef with context, a reminder that food is chosen into being, not just delivered.

You feel yourself adding to the room’s archive, another entry filed under Plenty and Patience.

When the pianist leans into something from Ellington, a toast rises two tables over and breaks into laughter at the second chorus. The roast tastes somehow warmer after that, like a chorus finds its third note.

You eat slower, to stay inside the song a little longer.

Logistics Without Cars: How To Get There Hungry

Reach Mackinac by ferry from St. Ignace or Mackinaw City, wind in your teeth and lake spray on your sleeves. Porters tag bags at the dock and they reappear in your room as if by friendly magic.

The horse carriage ride up the hill takes ten to fifteen minutes, enough time to let appetite settle and sharpen.

Build hunger with a shoreline walk before check in. Skip heavy snacks after lunch, sip water, and trust the dinner hour.

If you are staying off property, leave an extra cushion for the carriage queue and the pleasant distraction of shop windows on Main Street.

There is no car horn to hurry you, only hooves and bells. Accept the slower clock.

The prime rib reads that rhythm and responds in kind.

Beyond The Plate: Rooms, Pools, and That Morning After

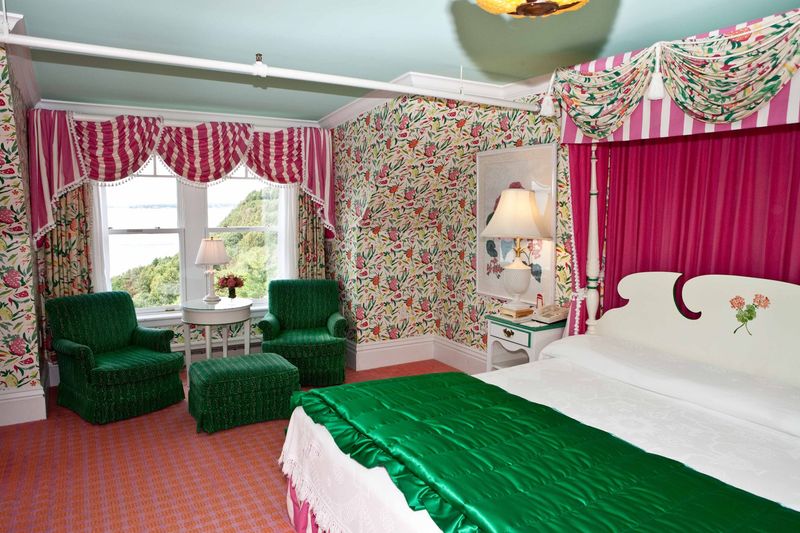

Sleep in rooms that look like someone painted summer and then dared the sun to compete. Bold florals, striped curtains, a wink of fringe, and a window that frames the bridge like a bookmark.

Morning begins with gulls and an almost theatrical brightness.

Swim the Esther Williams Pool if the day runs hot, or walk the lawn’s clipped edge lines to watch croquet balls click like polite arguments. The spa’s steam untangles travel, and the fitness room’s treadmills point toward trees so you do not miss the island while you earn breakfast.

By afternoon, hunger rebuilds on bikes and tennis courts.

Return to dinner with a cleaner appetite and steadier posture. The second night’s prime rib tastes different, a touch more pepper, a deeper patience in the slice.

It is amazing what rest does to flavor.

The Farewell Walk, And What Stays

You leave the way you arrived, slower than home usually allows. The porch is quiet, flags at rest, rocking chairs holding the shape of last night’s conversations.

Down the hill, the harbor blinks awake and a freighter turns like a planet changing seasons.

Breakfast coffee tastes faintly of last night’s jus because memory does that. You hear the carving cart’s wheels even on the ferry, a soft reminder under the engine’s hum that is not really there.

This is the kind of meal that alters how you look at clocks.

Back on the mainland, cement feels too loud at first. But the cadence returns in traffic lights and crosswalks, and you find yourself planning the next boat, the next porch seat, the next slice.

Some places feed you; the Grand teaches you to savor.