A cluttered lab bench, a missed measurement, a spark where no one expected it. History is full of breakthroughs that began as mistakes and side quests, then reshaped daily life.

As you read, you will feel the thrill of those chance moments and the curiosity that turned them into world changers. Ready to see how serendipity quietly built the modern world you know so well?

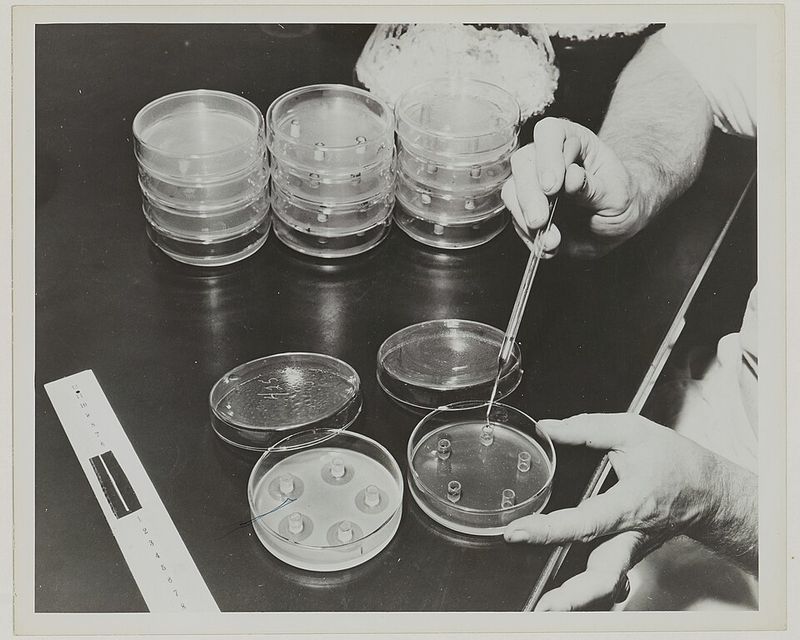

1. Penicillin

Picture a chilly London lab in 1928, dishes stacked like saucers after tea. Alexander Fleming returns from vacation and notices a rogue mold encroaching on his Staphylococcus plate.

Where the mold grows, bacteria vanish, leaving a crisp halo like frost around a windowpane. That small, messy surprise becomes the seed of penicillin, the first true antibiotic.

It took years of refinement by Florey, Chain, and Heatley to turn it into a workable drug, but the spark is that halo.

Within two decades, penicillin changes wartime medicine, saving soldiers from infections that once meant amputations or death. By mid century, antibiotics help push average life expectancy upward, and today the CDC estimates antibiotics avert millions of deaths annually worldwide.

You know the follow up too: antibiotic resistance keeps doctors cautious. Still, the origin story remains wonderfully human.

A forgotten dish. A curious glance.

And the resolve to test, test, and keep testing.

2. The Microwave Oven

In 1945, engineer Percy Spencer stands near an active magnetron, the humming heart of radar gear. He reaches into his pocket and finds a chocolate bar melted into a sweet catastrophe.

Curiosity flips a switch. He scatters popcorn kernels, watches them burst like tiny fireworks, then cages the effect in a metal box.

Commercial ovens arrive in factories and restaurants first, hulking and expensive, but convenience marches homeward.

By the late 1970s, countertop models shrink and prices fall, and suddenly weeknight cooking changes forever. Today, over 90 percent of U.S. households own a microwave, a statistic that tracks comfort as much as technology.

You might remember late night leftovers, a steaming mug of cocoa, or the first time you watched a cold slice become pizza again. The magic is simply dielectric heating, but it feels like time travel on demand.

An accidental pocket meltdown made speed a kitchen standard.

3. Post-it Notes

Spencer Silver at 3M sets out to make a super strong adhesive and instead creates a weak, pressure sensitive one that refuses to commit. For years it floats around the company as a solution searching for a problem.

Then colleague Art Fry, tired of bookmarks sliding from his church hymnal, dabs the adhesive onto scraps. They stick, unstick, and restick, leaving pages pristine.

Suddenly, reminders bloom like little flags across desks and calendars.

By 1980, those canary yellow squares become a quiet revolution in how you think on paper. Ideas no longer need a home inside notebooks.

They can migrate, cluster, and iterate in the open. Design sprints, to do lists, brainstorm walls, all powered by a failure turned feature.

The product’s charm is humility. It is not loud, not flashy, just precise friction.

That slight tack makes creativity visible and collaboration flexible. A gentle glue changed office life.

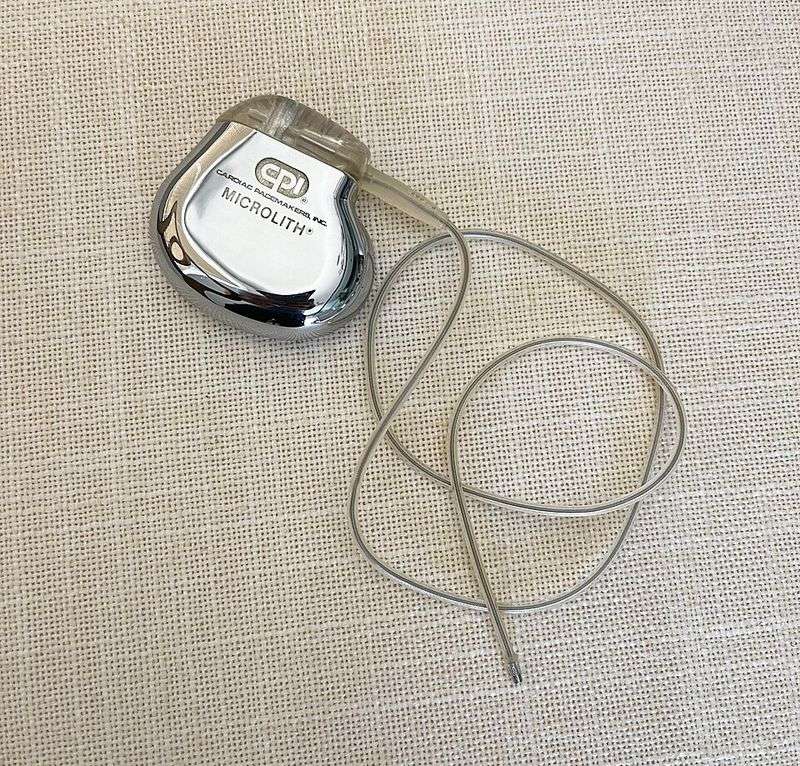

4. The Pacemaker

Wilson Greatbatch reaches for a resistor in 1956, grabs the wrong value, and turns a heart rhythm recorder into a steady pulse generator. The circuit ticks like a mechanical metronome, echoing the cadence of life itself.

That mistake becomes a prototype, then an implantable device small enough to rest under the skin, whispering current to a faltering heart. Early versions need periodic surgery for battery swaps, but reliability improves quickly.

Pacemakers now help millions live fuller lives, syncing with natural rhythms and adapting to activity. Modern models can last a decade or more.

According to the American Heart Association, hundreds of thousands of pacemakers are implanted globally each year, sustaining workdays, hikes, and quiet mornings with coffee. The origin is pure serendipity, but the legacy is rigor.

Careful testing, biocompatible materials, and honest conversations with patients. A misread resistor became endurance measured in heartbeats.

5. Velcro

George de Mestral returns from a Swiss hike in 1941 with burrs clinging to his trousers and his dog’s fur. Under a microscope he discovers tiny hooks grasping fabric loops like miniature grappling hands.

Nature sketches the blueprint. Years of trial lead to nylon hooks and loops that mate and separate with a satisfying rip.

The fastening system gets a playful name inspired by velvet and crochet, and suddenly closures feel effortless.

Astronaut suits, kids’ sneakers, cable management, blood pressure cuffs, and camping gear all adopt the idea. It is easy, repeatable, and resilient under grit and cold.

You probably know its sound better than its inventor. That tear is part of its charm, a quick confirmation things are secure.

Biomimicry before the word became common, Velcro proves observation can turn a nuisance into utility. Hooks, loops, and curiosity stitched a global staple.

6. Coca-Cola

In 1886, Atlanta pharmacist John Pemberton tinkers with a nerve tonic, blending kola nut caffeine with coca leaf extract and aromatic oils. At a soda fountain, someone adds carbonated water instead of plain, and the syrup blossoms into a fizzy, fragrant drink.

The taste is bright, spiced, and instantly sociable. Asa Candler later systematizes bottling and marketing, turning a regional curiosity into an international emblem stitched onto ballparks and lunch counters.

By the mid 20th century, contour glass bottles become icons photographed beside road trips and jukeboxes. Today Coca-Cola products reach over 200 countries, a footprint that maps both taste and logistics.

Health debates follow, as sugar intake and portion sizes grow. Still, the origin moment remains a happy mix up at a counter.

Tonic becomes treat, medicine becomes memory. A pharmacist’s experiment fizzes into global culture one pour at a time.

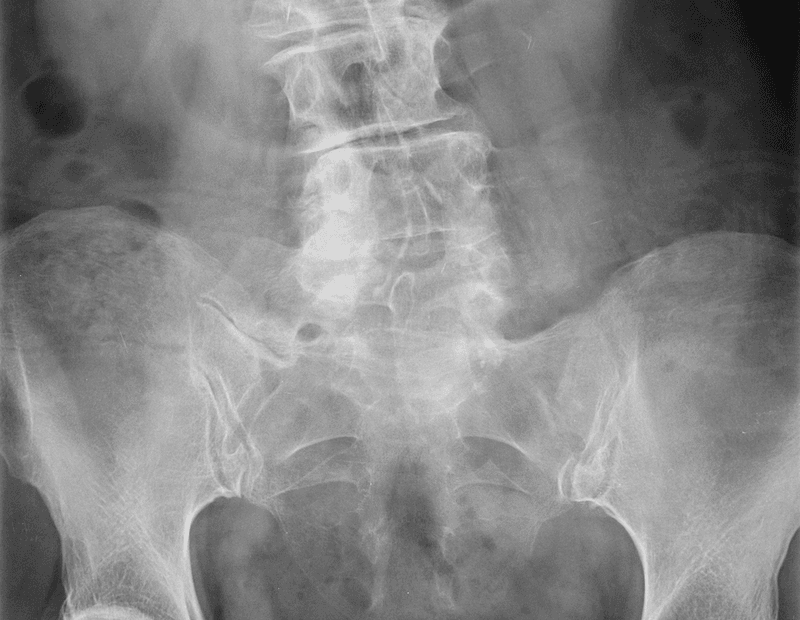

7. The X-Ray

Wilhelm Röntgen darkens his lab in 1895 and notices a fluorescent screen glowing even though it is shielded. Invisible rays are slipping through wood and cardboard.

He places his wife’s hand between the tube and a plate, and a spectral image appears, rings and bones like branches in winter. Within weeks, hospitals begin experimenting.

Surgeons can see bullets, fractures, and swallowed pins without a single incision.

X rays usher in diagnostic radiology, a discipline that now includes CT, mammography, and fluoroscopy. The transformation is immediate and global.

By the early 1900s, novelty parlors offer bone pictures, and physicians refine shielding to protect patients and staff. Today, billions of medical images are produced annually worldwide, guiding treatments with clarity once unimaginable.

The first picture is both eerie and intimate. A marriage band, a lattice of phalanges, and a century of seeing inside safely begins.

8. Safety Glass

Édouard Bénédictus drops a glass flask in 1903 and braces for the cascade. Instead, cracks spiderweb while the shell holds.

A thin coating of cellulose nitrate from a prior experiment keeps shards tethered. He patents laminated glass, a sandwich of glass and plastic that bends but resists shattering.

The world takes note as automobiles grow faster and streets more crowded.

By the 1920s, windshields adopt safety laminates, reducing lacerations from collisions. Modern versions use polyvinyl butyral or SGP interlayers, tough enough to keep a pane intact under fierce stress.

According to road safety studies, laminated windshields help maintain vehicle structure and passenger ejection resistance. You have pressed a forehead to one on rainy nights, tracing rivulets while city lights smear like paint.

That durability began with a near miss in a Paris lab, where a mistake became a shield for millions.

9. The Slinky

Richard James, a naval engineer in the 1940s, watches a torsion spring tumble off a shelf and step its way down like a polite escape artist. The movement feels alive.

He perfects the coil’s dimensions until it walks with rhythm, then demonstrates it in a Philadelphia department store. Crowds circle.

Children lean in, transfixed by a toy that obeys physics yet feels like play distilled.

Within two years, tens of thousands sell, and the Slinky becomes a fixture in stockings and science classes. Teachers use it to show transverse and longitudinal waves, a tactile introduction to energy.

The jingle gets stuck in your head, and the metal gleam becomes part of living room lore. Simple, sturdy, and oddly graceful, the Slinky proves that delight can spring from a stumble.

A fall from a shelf turned gravity into a stage show.

10. The Potato Chip

The legend lands in 1853 at Moon’s Lake House near Saratoga Springs. A fussy diner keeps sending back thick fried potatoes.

Chef George Crum, nudged by irritation and mischief, slices paper thin, fries them to a crackle, and salts them until they sing. The plate returns to the table and disappears.

Word spreads, and Saratoga Chips become a local specialty before factories bag the crunch for every picnic and lunch pail.

By the 20th century, continuous fryers and nitrogen flushed bags standardize freshness. Today the global potato chip market measures in the tens of billions of dollars annually, an empire built on thinness.

You know the sound of a bag opening on road trips, the salty dust on fingers you lick clean. From annoyance to indulgence, the chip’s path is deliciously human.

Precision slicing, hot oil, and a dare to go thinner made a classic.

11. Super Glue

Harry Coover hunts for crystal clear plastics for gun sights during World War II and stumbles on a family of cyanoacrylates that bond to nearly everything. Too sticky for optics, the formula is shelved.

Years later, the team revisits the chemistry and realizes its power. A single drop polymerizes in the presence of moisture, welding surfaces in seconds.

Industrial uses blossom first, then tiny tubes migrate to junk drawers and glove boxes.

Stories follow: emergency field closures of wounds, hobbyists fixing cracked ceramics, guitarists mending nails before a gig. The glue’s speed is both marvel and menace, so caps stick shut and fingers meet their match.

Still, its reliability earns trust across workshops and kitchens. A failed gun sight material turned into a universal fixer, living where patience runs thin and precision matters.

One misfit monomer made quick repairs a household ritual.

12. Teflon

Roy Plunkett is measuring refrigerant gas in 1938 when a cylinder refuses to release. Inside, tetrafluoroethylene has polymerized into a waxy, ultra slippery solid.

Chemists call it polytetrafluoroethylene, PTFE for short. It shrugs off heat, chemicals, and friction like a raincoat for atoms.

War applications come first, insulating wiring and sealing gaskets, before cookware transforms the polymer into morning routine comfort.

Nonstick pans flip omelets with confidence and reduce the scrubbing penalty of dinner. Engineers love PTFE for valves and bearings where stickiness kills efficiency.

With popularity comes scrutiny: manufacturers phase out certain processing chemicals under regulatory pressure and evolving scientific consensus. Still, the material remains a benchmark for low friction performance.

A clogged canister yielded the slipperiest of companions, cloaked in silver skillets and quiet industrial seals. Breakfast and rockets both owe something to that stubborn tank.

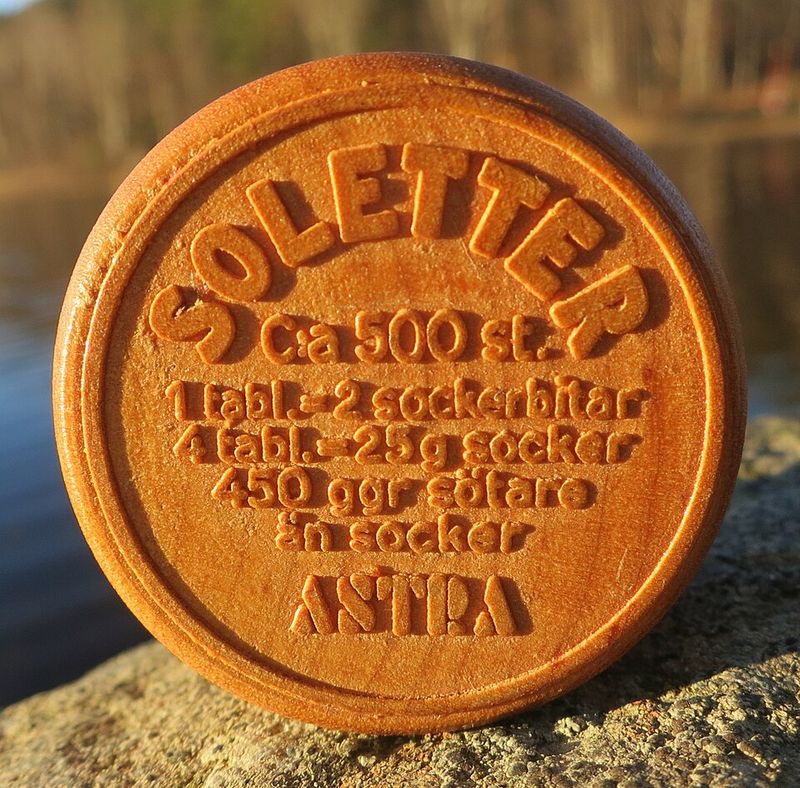

13. Saccharin

Constantin Fahlberg leaves the lab in 1879, sits down to supper, and tastes sweetness clinging to his fingertips. He traces it back to benzoic sulfinide, a compound he had been synthesizing from coal tar derivatives.

Suddenly there is a calorie free taste of sugar, cheap to make and shelf stable. Early demand rises during sugar shortages and wartime rationing, and coffeehouse counters gain a new bowl beside the cream.

Debates rumble on safety and aftertaste, but saccharin opens the door to an entire category of sweeteners. Diet sodas and diabetic friendly recipes follow, expanding choice in a world balancing pleasure and health.

The FDA’s regulatory arc tightens labels and then eases warnings as data evolve. You know the pink packet wink at diners, pragmatic and nostalgic.

A forgotten hand wash redirected dessert, proving small lapses can rewrite flavor itself.

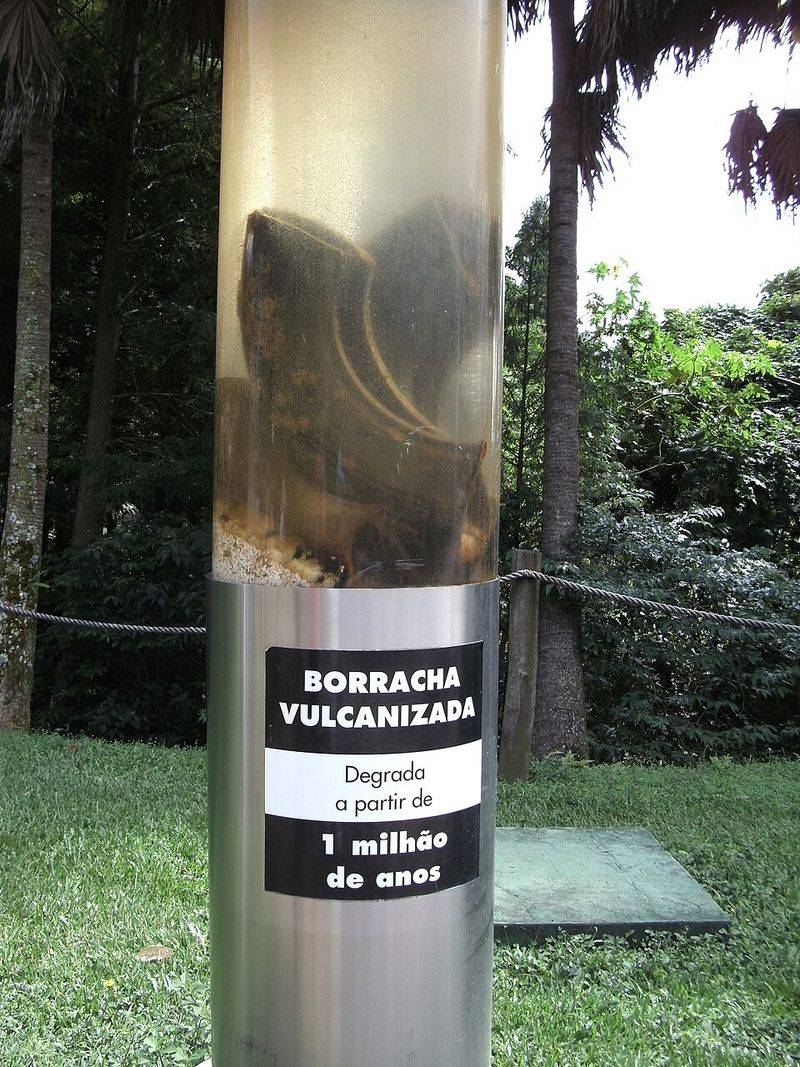

14. Vulcanized Rubber

Charles Goodyear, deep in debt and obsessed with taming rubber’s moods, drops a sulfur sprinkled sample onto a hot stove around 1839. Instead of melting into sticky tar, it toughens, elastic yet firm, like tanned leather with bounce.

He has stumbled onto vulcanization, a crosslinking process that stabilizes rubber across seasons. Boots stop sagging in summer, carriage tires grip in rain, and gaskets finally keep steam where it belongs.

Industry blooms. By the early 20th century, automobiles lean on vulcanized rubber for tires that carry families across newly paved roads.

The name Goodyear outlives the man, tied to blimps and speedways. Today, billions of tires roll worldwide, each a descendant of that hot stove moment.

You feel it in the hush of a well padded ride and the snap of a basketball on a court. Heat, sulfur, and stubbornness built modern motion.

15. The Popsicle

Frank Epperson is eleven in 1905 when he leaves a cup of powdered soda and water on the porch with a stir stick. Overnight frost grabs the mixture and locks the stick like a handle.

By morning, the treat peels free, a handheld shard of summer before the idea even has a name. He calls it the Eppsicle at first, then Popsicle wins out as street vendors and beachgoers adopt the chill.

Patent papers follow, and by the 1920s, two stick versions encourage friendly sharing. Flavors multiply, from orange to cherry to blue raspberry that stains tongues with pride.

In heat waves, sales spike, a data line that maps directly onto thermometers. You remember the drip race down knuckles, the bite that numbs teeth.

From a forgotten cup grew a ritual of shade, sugar, and a stick that made childhood cooler.

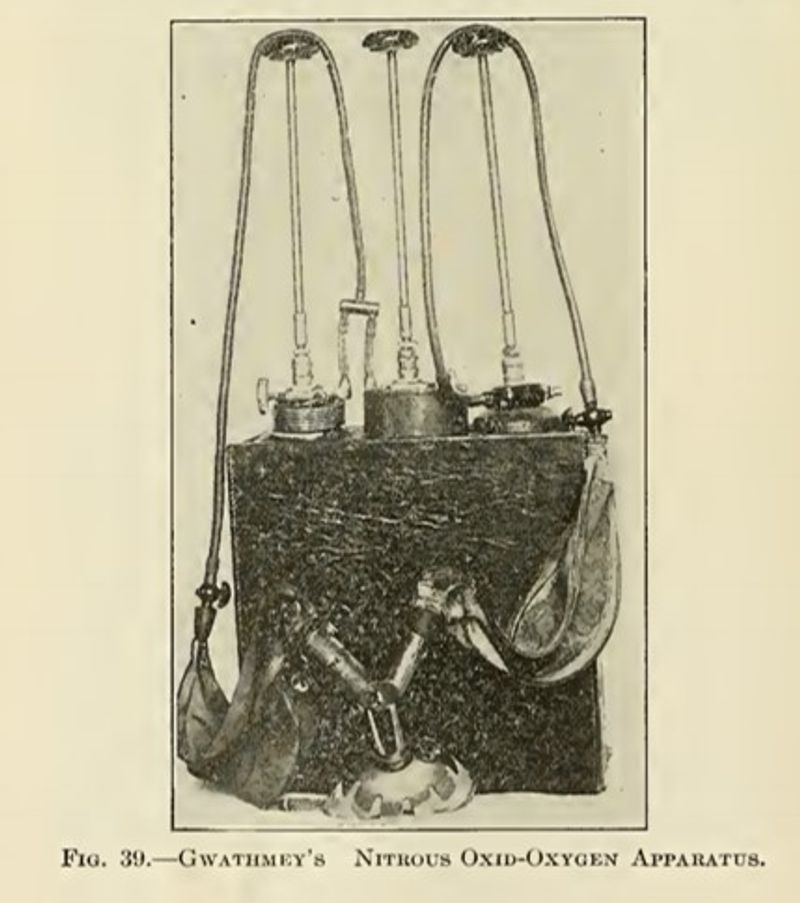

16. Nitrous Oxide as Anesthesia

In the 1840s, traveling shows feature nitrous oxide as party trick fuel. Spectators giggle, bump into furniture, and feel no pain.

Dentist Horace Wells attends a demonstration and notices a participant injure himself without flinching. He tries the gas during a tooth extraction and glimpses the future.

Although his early public demo falters, the insight sticks: gases can quiet pain.

Ether and chloroform quickly enter operating rooms, then modern anesthesia blossoms into a balanced art combining gases, IV agents, and careful monitoring. Nitrous oxide remains a staple in dental suites and delivery rooms for its short acting calm.

Anesthesia helps enable complex surgeries that extend life and quality. The American Society of Anesthesiologists notes dramatic reductions in surgical mortality since the 20th century.

A carnival curiosity became a clinical cornerstone, turning dread into manageable moments under practiced care.

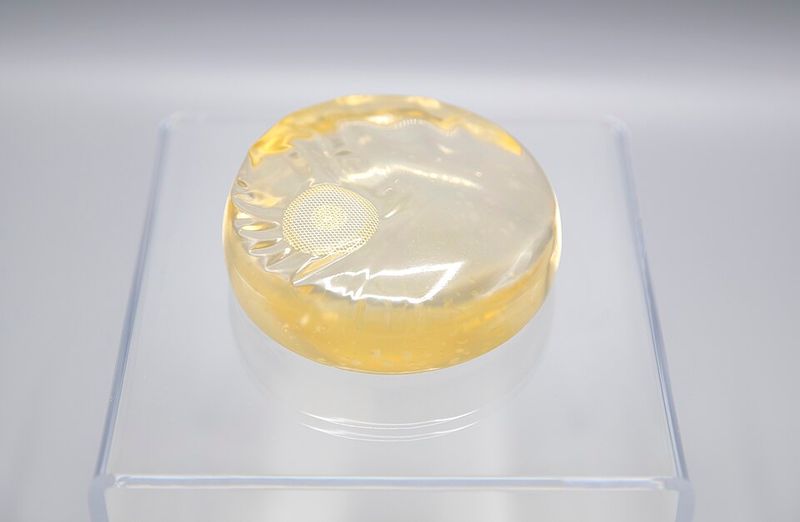

17. The Implantable Silicone Breast Implant

In the early 1960s, Houston surgeons Thomas Cronin and Frank Gerow experiment with materials that might mimic human tissue. Silicone gel feels unexpectedly lifelike under the glove.

The first implants are teardrop shaped, with a textured exterior to reduce shifting. A volunteer patient steps forward, and cosmetic surgery enters a new era centered on choice and reconstruction.

The cultural conversation grows complex, mixing autonomy, aesthetics, and medical risk.

Over decades, device designs iterate to improve durability and reduce leakage. Regulatory scrutiny tightens, pauses, and reapproves as data accumulate.

Today, silicone implants are among the most studied devices, and reconstructive uses after mastectomy carry deep emotional stakes. You can feel the duality here: innovation born from curiosity, then stewarded by consent, follow up, and science.

A material that felt like flesh reshaped both practice and perception of body image.

18. Play-Doh

Before it lived in rainbow tubs, Play-Doh scrubbed soot from wallpaper. In the 1950s, as homes shifted to washable paint and gas heating, sales of the cleaner sagged.

A teacher’s tip reframed the putty as a classroom modeling compound. The company removed detergent, added color and a soft scent, and watched kids knead monsters, pizzas, and alphabet snakes.

Newspapers and TV shows amplified the charm, and art tables found a permanent resident.

By the 1960s, millions of cans shipped annually, a tactile antidote to tidy living rooms. The National Toy Hall of Fame would eventually enshrine it for sparking open ended creativity.

You recognize the smell instantly, a cozy hint of childhood projects and crumb covered carpets. An obsolete product pivoted into play, proving that purpose can be remixed with a single teacher’s observation and a softer formula.

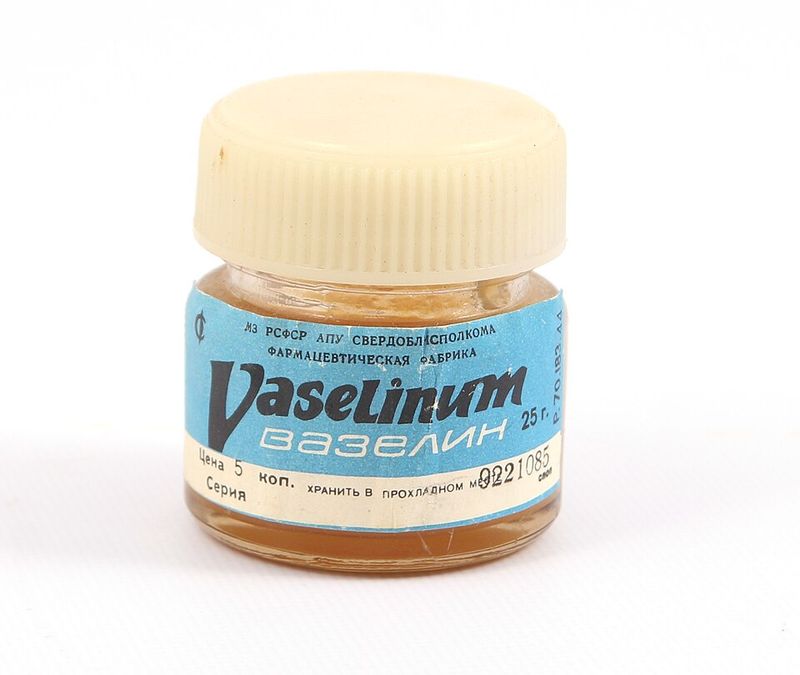

19. Vaseline

Robert Chesebrough visits oil fields in the 1860s and notices workers smearing a waxy residue from pump rods onto cuts and burns. The goo protects skin from grit and helps healing.

Back in his lab, he refines the stuff into petroleum jelly and baptizes it Vaseline. He demonstrates by burning his arm and applying the salve at public lectures, a dramatic sales pitch that belongs to another age.

Households embrace it for chapped lips, scrapes, and squeaky hinges, a Swiss Army jar on bathroom shelves. Modern dermatology parses when occlusives help and when to reach for something else, but the product’s staying power is obvious.

A byproduct became a brand, then a ritual of winter nights and dry hands. You have twisted that metal cap, scooped a pearl with a finger, and felt wind lose its bite.

20. The Ice Cream Cone

At the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, an ice cream vendor runs out of dishes as summer crowds press in. A neighboring waffle purveyor rolls his thin pastries into cones, and suddenly handheld sundaes roam the fairgrounds.

Stories differ on which stand sparked the idea, but the delight is the same. A crisp shell that hugs cold cream, portability that turns dessert into a stroll.

By decade’s end, cone makers crank out perfectly scalloped edges, and soda fountains add sprinkles, nuts, and chocolate dips. The pairing becomes inseparable in memory and marketing.

Industry data show billions of cones consumed annually worldwide, proof that convenience can be delicious theater. You have raced melting edges on a July sidewalk, catching drips with a swivel of the wrist.

An empty stack of dishes birthed a classic spiral of joy.