Black feminism didn’t just appear out of nowhere. It was built word by word, essay by essay, by women who refused to be erased from their own liberation movements.

These writers spoke truth when it was dangerous, named injustice when it was invisible, and created language for experiences the world tried to silence. Their words didn’t just shape Black feminism—they made it possible.

Sojourner Truth

The mic drop started in 1851. Her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech challenged racism and sexism in one fierce breath, and it still reads like a direct message to the present.

Truth didn’t write it down herself, but her spoken words became one of the most quoted feminist texts in history. She stood at that Ohio women’s convention and asked questions that exposed the hypocrisy of white feminism and the racism embedded in gender roles.

She worked fields, bore children, and endured enslavement, yet white women’s movements acted like Black women didn’t exist.

Her speech wasn’t polite. It wasn’t asking for permission.

It was a challenge to both movements to recognize Black women as fully human, fully women, and fully deserving of rights.

Truth’s words laid groundwork that would echo through every wave of feminism that followed. She proved that intersectionality wasn’t invented in the 1980s—it was lived and spoken about over a century earlier.

Her legacy is proof that Black women have always been ahead of the conversation, even when the conversation tried to leave them behind.

Anna Julia Cooper

One book, one thesis: respect Black women or watch your progress crawl. Her 1892 collection A Voice from the South is often cited as an early full-length Black feminist text, and it pushes education and dignity with zero patience for nonsense.

Cooper was a scholar, teacher, and someone who believed Black women’s voices were essential to any real progress. She wrote about how society measured advancement by how it treated its most marginalized, and she made it clear that Black women were the litmus test.

If they weren’t free, nobody was.

She didn’t just theorize. Cooper lived it, earning a PhD in her sixties at a time when most people thought Black women had no business in higher education.

Her work addressed racism in feminist movements and sexism in Black liberation efforts, calling out both with surgical precision.

A Voice from the South remains a foundational text because it named what so many tried to ignore. Cooper’s insistence on education, respect, and full humanity for Black women set a standard that still holds today.

Ida B. Wells

She turned truth into a weapon and aimed it at terror. In Southern Horrors (1892), Wells documented lynching and exposed the lies used to justify violence, refusing to let Black women and Black communities be silenced.

Wells was a journalist who risked her life to investigate and report on racial violence. She didn’t just write about injustice—she tracked it, named it, and dismantled the myths that protected it.

Her work showed how accusations against Black men were often fabricated to maintain white supremacy, and she refused to back down even when threatened.

As a Black woman in a deeply racist and sexist society, Wells faced danger from all sides. Her newspaper office was destroyed, and she was forced to relocate.

But she kept writing, kept speaking, and kept organizing.

Her investigative journalism laid the foundation for what would become civil rights activism. Wells showed that Black women could lead movements, challenge power, and reshape narratives.

Her courage and commitment to truth-telling made her an icon whose work still informs anti-racist and feminist organizing today.

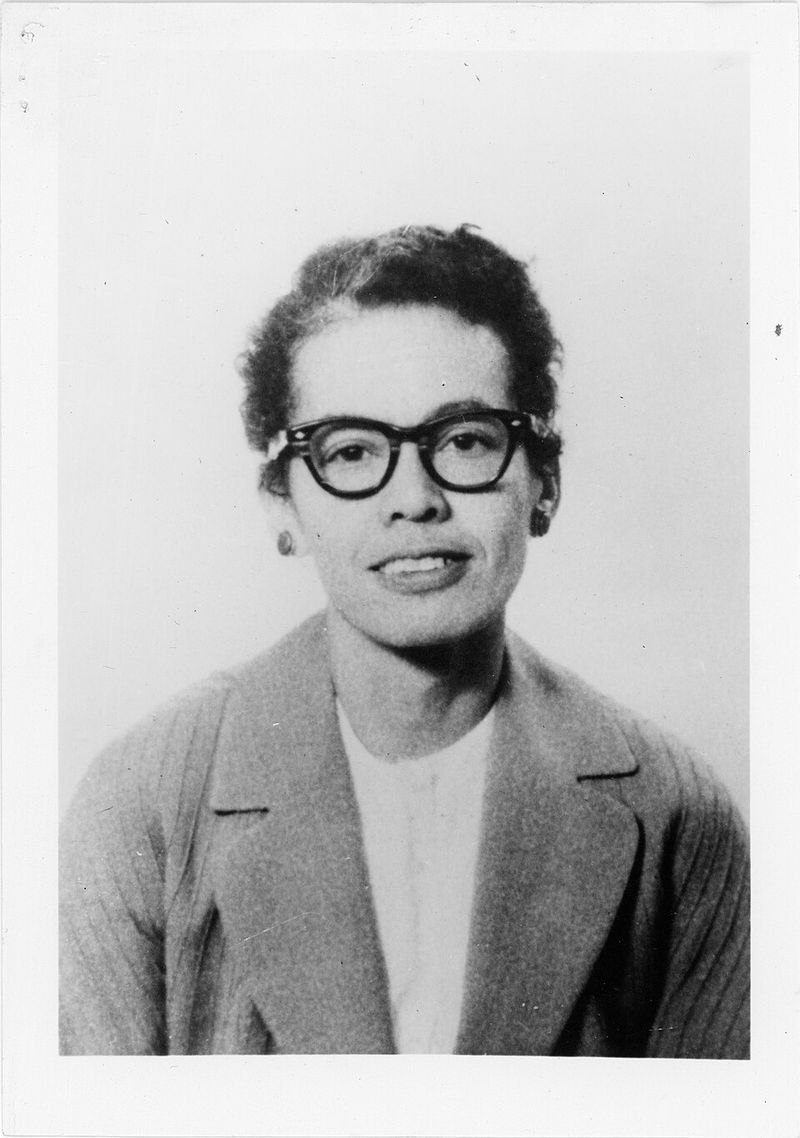

Pauli Murray

“Jane Crow” is the phrase that makes the whole room go quiet. Murray named the intersecting discrimination Black women faced, giving language to what many lived but were told to swallow.

Murray was a lawyer, activist, poet, and priest who spent a lifetime fighting systems that tried to box them in. They understood that Jim Crow laws weren’t just about race—they hit Black women differently, and that difference mattered.

Murray’s coining of “Jane Crow” gave activists and scholars a way to talk about gendered racism that wasn’t just theoretical.

Murray also co-founded the National Organization for Women and influenced Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s legal strategies on gender discrimination. Their work on civil rights law helped dismantle segregation and expand protections for women and marginalized communities.

Murray’s life and work were ahead of their time. They lived openly as queer and gender nonconforming, even when the world had no language for it.

Their intellectual contributions continue to shape feminist, legal, and LGBTQ+ scholarship, proving that Black feminist thought has always been expansive and intersectional.

Claudia Jones

She called out the “neglect” and meant it like an alarm bell. In her 1949 essay “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman,” Jones argued that Black women’s oppression was being ignored even in progressive movements.

Jones was a communist organizer and journalist who saw that even leftist spaces weren’t centering Black women’s struggles. Her essay made it clear that Black women faced triple oppression—race, class, and gender—and that any movement ignoring that reality was incomplete.

She didn’t mince words, and she didn’t wait for permission to speak.

Her activism got her deported from the United States during the Red Scare. She moved to London and continued organizing, founding the West Indian Gazette and helping establish the Notting Hill Carnival.

Her work connected Black liberation struggles across continents.

Jones’s insistence that Black women’s issues were central, not peripheral, influenced generations of Black feminist thought. Her essay remains a foundational text because it demanded that movements actually practice the liberation they preached.

Audre Lorde

She did not come to play nice with “single issue” thinking. Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” (1984) is a sharp reminder that feminism without difference is just exclusion in a prettier outfit.

Lorde was a poet, essayist, and self-described “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” Her work insisted that all parts of identity mattered and that movements couldn’t just pick and choose which oppressions to address. She called out white feminism for ignoring race, straight feminism for ignoring sexuality, and any movement that asked marginalized people to wait their turn.

Her essay on the master’s tools became a rallying cry. It argued that using the same oppressive systems wouldn’t lead to liberation—you had to build something new.

Lorde’s writing was both personal and political, blending memoir, theory, and poetry in ways that felt revolutionary.

Her influence on Black feminist thought, queer theory, and intersectional activism is massive. Lorde didn’t just write about difference—she celebrated it, insisting that our differences were sources of strength, not division.

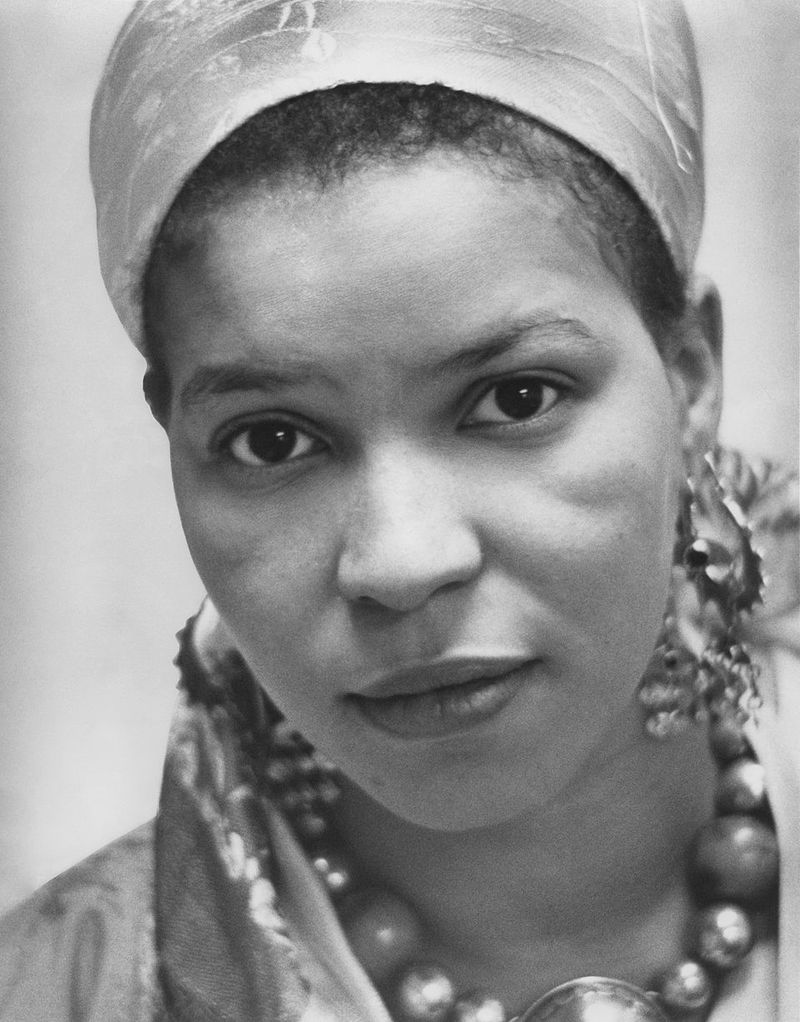

Ntozake Shange

She made poetry feel like a survival kit. for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf (premiered mid-1970s) centers Black women’s pain, joy, and endurance with a voice you can’t un-hear.

Shange’s choreopoem wasn’t just a play—it was a ritual, a testimony, a collective exhale. It told stories of Black women navigating love, trauma, violence, and resilience in a world that tried to break them.

The work was raw, honest, and healing, giving language to experiences that mainstream theater ignored.

The piece became a cultural phenomenon, resonating with Black women who saw themselves reflected on stage for the first time. Shange’s use of poetry, movement, and music created a new form that honored Black women’s complexity and creativity.

It wasn’t trying to be palatable—it was trying to be true.

Shange’s work influenced generations of writers, performers, and activists. She proved that Black women’s stories deserved center stage and that art could be both beautiful and politically powerful.

Her legacy lives on in every piece of theater that refuses to soften Black women’s realities.

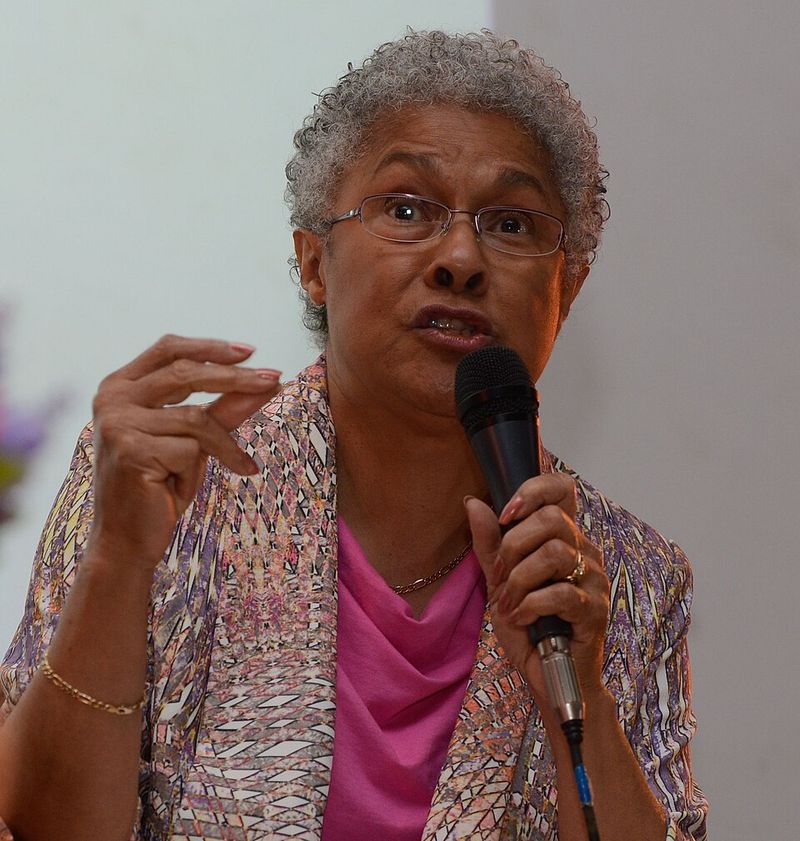

bell hooks

I opened Ain’t I a Woman and immediately got humbled. Published in 1981, it names how racism and sexism shaped Black women’s lives and critiques movements that claimed liberation while leaving Black women behind.

hooks wrote with clarity and urgency, tracing the history of Black women’s oppression from slavery through the feminist and civil rights movements. She showed how both movements failed Black women, and she didn’t sugarcoat it.

Her analysis was sharp, her examples were concrete, and her conclusions were undeniable.

The book became a foundational text in Black feminist theory and women’s studies. hooks didn’t just critique—she offered a vision of feminism that was inclusive, intersectional, and transformative. She argued that true liberation required dismantling all systems of oppression, not just the ones that affected some women.

hooks’s accessible writing style made complex theory understandable without dumbing it down. She believed feminist thought should be for everyone, not just academics.

Her work continues to inspire activists, scholars, and anyone seeking a feminism that actually liberates.

Barbara Smith

If you’ve ever said “identity politics,” you owe a thank-you. Smith helped found the Combahee River Collective and shaped a radical Black feminist tradition that centered Black women, including Black lesbians, without apology.

Smith was a writer, activist, and editor who understood that Black feminism had to include all Black women, not just the ones deemed acceptable. She co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, which published works by women of color when mainstream publishers wouldn’t.

Her work made space for voices that had been erased.

Smith’s activism wasn’t just theoretical. She organized, she edited, she built institutions, and she showed up.

Her commitment to centering Black lesbians in feminist work was revolutionary at a time when homophobia was rampant in both Black and feminist communities.

Her contributions to Black feminist thought are immeasurable. Smith insisted that liberation had to be for everyone or it wasn’t liberation at all.

Her work laid the foundation for queer Black feminism and continues to influence organizing and scholarship today.

Angela Davis

She made it impossible to separate race, class, and gender. In Women, Race & Class (1981), Davis threads U.S. history through a lens that insists liberation has to be structural, not just symbolic.

Davis is a scholar, activist, and revolutionary whose work connects historical analysis with contemporary struggles. Her book examined how race, gender, and class shaped movements for abolition, suffrage, and labor rights.

She showed how white women’s movements often excluded and exploited Black women, and how capitalism and racism were deeply intertwined.

Davis didn’t just write theory—she lived it. Her activism landed her on the FBI’s Most Wanted list, and she became a global symbol of resistance.

Her commitment to abolition, both of prisons and of oppressive systems, continues to inspire movements today.

Women, Race & Class remains essential reading because it refuses simplistic narratives. Davis’s analysis demands that we understand history’s complexity and that we build movements capable of addressing multiple forms of oppression.

Her work is a reminder that liberation requires more than good intentions—it requires systemic change.

Alice Walker

One word changed the conversation: womanism. Walker coined the term and expanded it in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens (1983), opening a door for Black women’s experience and culture to be centered on their own terms.

Walker created “womanism” to describe a feminism rooted in Black women’s history, culture, and survival. She wanted a term that honored the strength, creativity, and resilience of Black women without erasing their specific experiences.

Womanism wasn’t just feminism with a different name—it was a different framework entirely.

In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens collected essays that explored Black women’s creativity, spirituality, and resistance. Walker wrote about her mother’s garden, Zora Neale Hurston’s legacy, and the ways Black women created beauty in the face of oppression.

Her writing was personal, poetic, and political.

Walker’s contribution to Black feminist thought was profound. She gave Black women a language to describe their own liberation, one that didn’t require approval from white feminism.

Womanism has since been adopted and expanded by scholars, theologians, and activists worldwide, proving the power of naming your own experience.

Toni Morrison

Morrison didn’t write stories—she built entire worlds where Black women’s lives mattered completely. Her novels like “Beloved” and “The Bluest Eye” forced America to confront its brutal past and present.

She won the Nobel Prize in Literature, but her real achievement was showing that Black women’s interior lives deserved center stage. Morrison refused to explain Blackness to white readers, writing instead for her own community first.

Her work laid bare how racism and sexism crush spirits, but also how Black women survive and create beauty anyway. Every sentence she wrote was an act of resistance and reclamation.

Patricia Hill Collins

Collins gave Black feminism its intellectual framework. Her concept of “intersectionality” before the term went mainstream showed how race, class, and gender lock together to create unique forms of oppression.

“Black Feminist Thought” became required reading because it named what Black women always knew but couldn’t find in textbooks. She validated the knowledge that comes from lived experience, not just ivory tower theory.

Collins transformed sociology by insisting that Black women’s standpoint matters as scholarship. Her work bridges activism and academia, proving that rigorous thinking and revolutionary politics belong together in the same conversation.

Zora Neale Hurston

Hurston celebrated Black Southern culture when everyone else treated it like something to escape. “Their Eyes Were Watching God” gave us Janie Crawford, a Black woman who chose herself over society’s expectations.

She was an anthropologist who knew her own people’s stories deserved preservation and respect. Hurston wrote in dialect without apology, capturing the poetry of everyday Black speech that academics dismissed as inferior.

Though she died broke and forgotten, later Black feminists resurrected her work and recognized her genius. She proved that Black women’s romantic lives, spiritual journeys, and self-discovery stories were literature worth celebrating.

Maya Angelou

“I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” broke every rule about what Black women could say publicly. Angelou wrote about rape, racism, and resilience with unflinching honesty that shocked and healed readers simultaneously.

Her autobiographies showed that personal story is political story, that one Black woman’s journey reflects collective struggles. She transformed pain into power through language that sang even while it testified to horror.

Angelou became a living symbol of Black women’s strength, reciting poetry at presidential inaugurations and speaking truth globally. Her work insists that surviving isn’t enough—Black women deserve to thrive, create, and claim joy as revolutionary acts.