The legendary Apache warrior who outmaneuvered thousands of soldiers for decades ended his days not in the sweeping deserts of the Southwest, but on the plains of southern Oklahoma. His final chapter unfolded behind the walls of a military installation that had witnessed the transformation of the American frontier.

For nearly two decades, this fort held one of history’s most formidable resistance fighters as a prisoner of war, far from his ancestral homeland. Walking these grounds today offers a rare glimpse into the complex final years of a man who became both a symbol of indigenous resistance and a curiosity of the American public.

The Fort That Changed the Frontier

At 435 Quanah Rd in Lawton, Oklahoma, you’ll find a military installation that played a pivotal role in shaping the American West. The fort was established in 1869 as a cavalry outpost tasked with managing relations between settlers and Native American tribes.

What struck me most during my visit was how authentically preserved the original structures remain. The stone buildings surrounding the old parade ground still stand exactly as they did over 150 years ago, though some now serve as officer housing.

The museum staff recommended I start with the 20-minute orientation film, which provided essential context for understanding the fort’s evolution from frontier outpost to modern military training center. This background made exploring the exhibits far more meaningful.

The fort’s strategic location allowed the military to monitor tribal movements across the southern plains. Over time, its mission shifted from active combat operations to serving as a detention facility for captured Apache warriors.

I spent nearly three hours wandering the grounds, and the weight of history felt palpable in every corner. The original quadrangle remains the heart of the historic site, offering visitors a genuine connection to frontier military life.

Apache Prisoners Behind Military Walls

Following the surrender of Geronimo and his band in 1886, the U.S. government faced a question: what to do with the Apache warriors who had resisted for so long? The answer came in the form of prisoner-of-war status, and Fort Sill eventually became their home.

The Apache prisoners arrived here in 1894 after spending time at facilities in Florida and Alabama. The transition to Oklahoma represented yet another displacement for people already torn from their southwestern homelands.

During my visit, a knowledgeable docent explained how the Apache community established a village on fort grounds. They built homes, farmed the land, and attempted to maintain their cultural identity despite their captive status.

The museum displays photographs showing Apache families going about daily life within the confines of military supervision. Children attended school, adults worked various jobs, and elders tried to preserve traditions for younger generations.

What the exhibits make clear is that these weren’t simply prisoners in cells. The Apache people created a functioning community under extraordinarily difficult circumstances, maintaining dignity and cultural practices despite their loss of freedom and ancestral lands.

The Warrior’s Final Years on the Plains

Geronimo spent his final 23 years at Fort Sill, arriving as a 65-year-old prisoner and remaining until his passing in 1909. The contrast between his life as a free warrior and his years in captivity couldn’t have been starker.

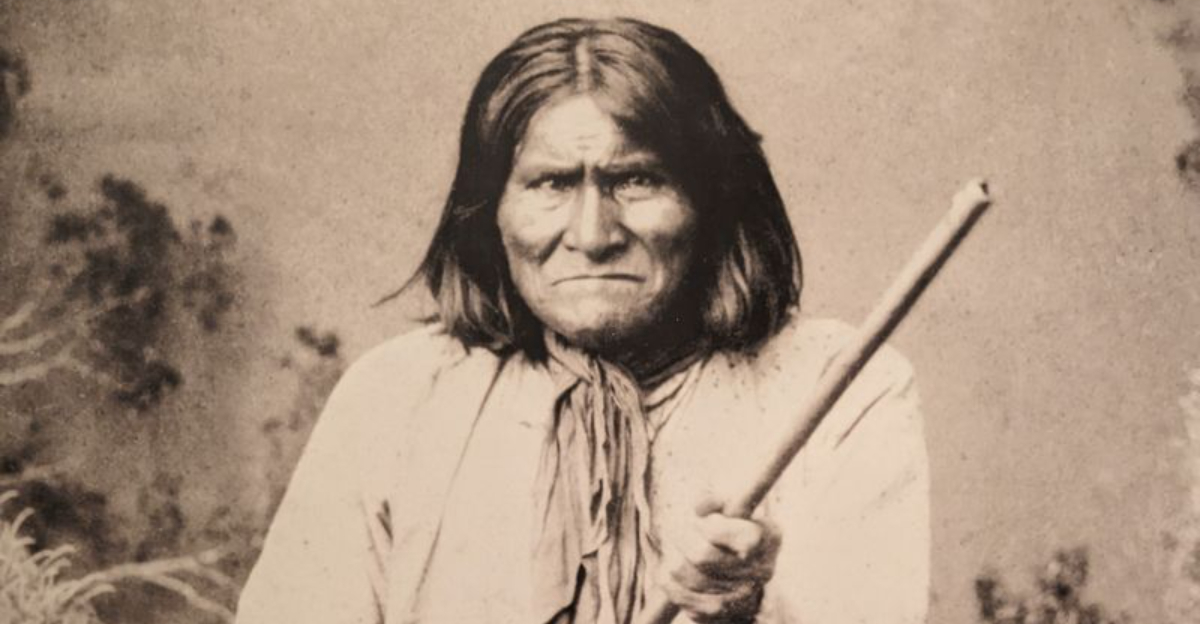

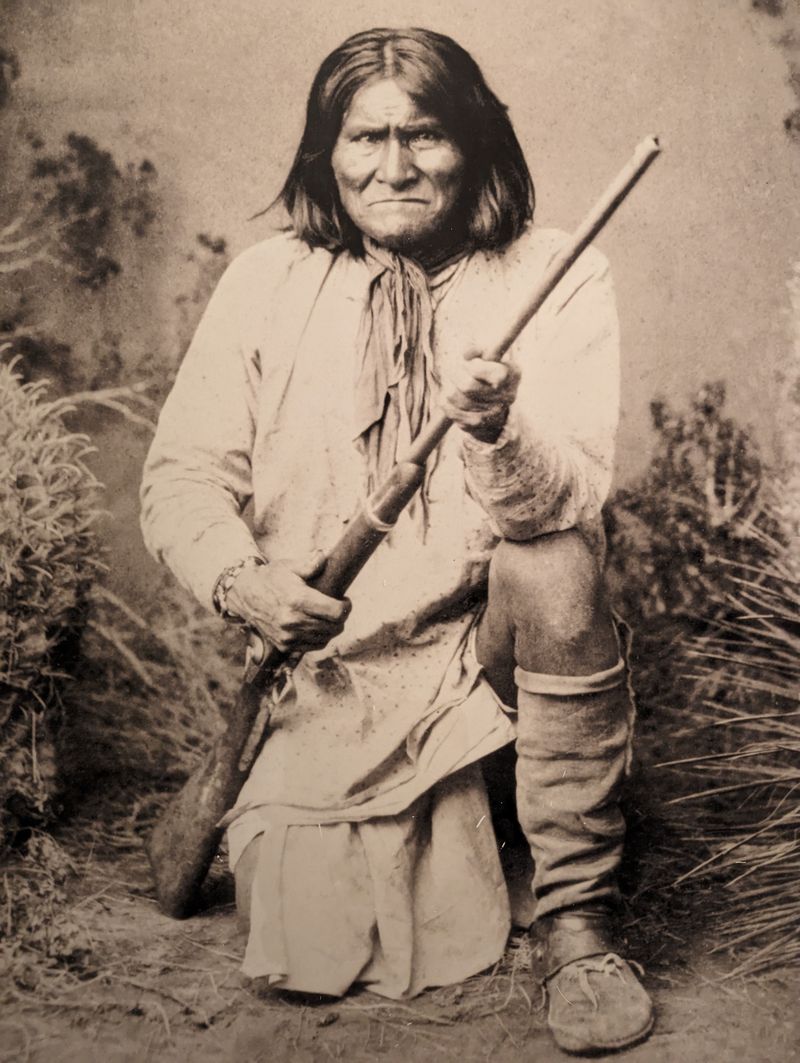

The museum houses fascinating artifacts from this period, including photographs of Geronimo in both traditional Apache dress and Western clothing. These images reveal the complicated reality of his captivity.

He became something of a celebrity during these years, appearing at public events including the 1904 World’s Fair and Theodore Roosevelt’s presidential inauguration. The government essentially put him on display, capitalizing on public fascination with the legendary warrior.

According to the exhibits, Geronimo earned money by selling photographs of himself and handcrafted items to curious visitors. He dictated his autobiography during this time, ensuring his version of events would survive.

The docent I spoke with emphasized that despite his fame, Geronimo never stopped petitioning for permission to return to Arizona. He remained a prisoner until his final day, never again seeing the mountains where he was born and raised.

The 1869 Cavalry Barracks Experience

One building transported me directly into the daily existence of frontier cavalry soldiers. The barracks has been meticulously restored to reflect life around 1890-1900, complete with period-accurate furnishings and equipment.

Rows of narrow bunks line the walls, each with a small footlocker for personal belongings. The sparse accommodations reminded me just how harsh military life was on the frontier, with minimal comfort and little privacy.

Personal items scattered throughout the display include shaving kits, letters from home, playing cards, and well-worn boots. These small touches humanized the soldiers who once occupied this space.

The barracks also showcases the weapons and tack used by cavalry units. Saddles, rifles, sabers, and grooming equipment for horses fill display cases, illustrating the soldier’s dual role as both warrior and horseman.

What made this exhibit particularly effective was the attention to authentic detail. Rather than a sanitized museum display, the barracks feels lived-in, almost as if the soldiers just stepped out for morning drill and might return any moment to their bunks and belongings.

Walking the Historic Quadrangle

The old parade ground forms the centerpiece of the historic district, surrounded by original limestone structures that have weathered more than 150 years of Oklahoma seasons. Officers still reside in some of these buildings today, creating a unique blend of past and present.

I downloaded the free audio tour accessible by cell phone, which guided me around the quadrangle while providing historical context for each building. The tour took about an hour and enriched my understanding considerably.

The limestone used in construction came from local quarries, giving the buildings a distinctive appearance that reflects the regional geology. Screen porches added in later years provide a somewhat incongruous but practical modification to the original architecture.

As I walked, I tried imagining this space during Geronimo’s time here. The parade ground would have been the site of military drills, formations, and ceremonies, all within view of the Apache prisoners living nearby.

The juxtaposition of active military housing within a historic landmark creates an unusual dynamic. Laundry hanging on porches and cars parked outside remind you that this isn’t just a preserved relic but a living piece of military history.

The Apache Cemetery and Final Resting Place

Perhaps the most somber part of my visit was the Apache cemetery, where Geronimo and other Apache prisoners of war are laid to rest. The cemetery sits on fort property, requiring base access to visit.

Geronimo’s grave has become something of a pilgrimage site, marked by a distinctive pyramid of stones. Visitors have left coins, feathers, and other tokens of respect, creating an informal memorial that grows continuously.

The cemetery contains dozens of graves belonging to Apache people who never returned to their homeland. Each marker represents a life lived in captivity, far from the southwestern deserts and mountains they called home.

The staff at the museum desk provided directions to the cemetery, emphasizing its significance as a bucket-list destination for many history enthusiasts. They also explained the protocols for respectful visitation.

Standing at these graves, I felt the full weight of this chapter in American history. These individuals, including one of the most famous resistance fighters in history, remained prisoners even in passing, buried in Oklahoma soil rather than their ancestral lands in the Southwest.

Military Artifacts and Regimental History

The museum houses an impressive collection of military artifacts spanning from the post-Civil War era through modern times. Glass cases contain uniforms, weapons, personal effects, and equipment that tell the story of frontier military life.

Buffalo Soldier regiments receive particular attention in the exhibits, highlighting the African American cavalry and infantry units that served at Fort Sill. Their contributions to frontier military operations are documented through photographs, uniforms, and personal accounts.

I was fascinated by the variety of weaponry on display, from single-shot cavalry carbines to early repeating rifles. The evolution of military technology becomes apparent as you move through the chronological exhibits.

Personal letters and diaries provide intimate glimpses into soldier experiences. These firsthand accounts describe everything from daily routines to encounters with Native American tribes, offering perspectives that official military records often omit.

The exhibits also cover the fort’s transition from frontier outpost to its current role as a major artillery training center. This continuity of military purpose spanning more than 150 years makes Fort Sill unique among American military installations, connecting past and present in tangible ways.

The Gift Shop and Historical Resources

The museum gift shop offers more than typical tourist souvenirs. I found an excellent selection of historical books covering Fort Sill, Geronimo, Apache history, and the frontier military experience.

Staff members working the shop proved incredibly knowledgeable and helpful. They answered questions about the exhibits, provided recommendations for other sites to visit on base, and shared insights about local history.

The shop stocks Geronimo-related items including reprints of his autobiography, photographic collections, and scholarly works examining his life and legacy. For anyone wanting to understand his story more deeply, these resources are invaluable.

I appreciated that proceeds from gift shop sales help support the museum’s operations and preservation efforts. The museum itself is free to enter, with only a donation box at the entrance, making the gift shop an important revenue source.

Beyond books, the shop carries reproduction historical items, Native American crafts, and military memorabilia. Everything felt thoughtfully curated rather than randomly assembled, reflecting the same attention to authenticity evident throughout the museum itself.

Planning Your Visit to the Base

Visiting Fort Sill requires some advance planning since it’s an active military installation. You’ll need to obtain a visitor pass at the gate, which requires presenting valid identification and vehicle registration.

The museum itself operates on limited hours, typically Tuesday through Saturday from 10 AM. I learned the hard way that government shutdowns can affect operations, so calling ahead at 580-442-5123 is wise before making the trip.

Admission to the museum is free, though donations are encouraged to help maintain operations. The suggested donation is around ten dollars, which seems more than fair given the quality and breadth of exhibits.

If you’re a military history enthusiast, plan to spend at least half a day here. The nearby Field Artillery Museum offers another fascinating stop, and together they provide a comprehensive look at Fort Sill’s military heritage.

The outdoor artillery displays on the museum lawn are accessible even when the indoor exhibits are closed. These well-maintained pieces include informative placards, allowing you to learn something even if timing doesn’t work out for the interior displays.

Connecting Past and Present

What makes Fort Sill remarkable is how seamlessly it integrates historical preservation with its continuing military mission. Modern soldiers train on the same grounds where cavalry once drilled, creating a living connection to the past.

The fort remains a major artillery training center, carrying forward the legacy established in its earliest days. You might hear the distant boom of artillery fire during your visit, a reminder that this isn’t merely a preserved historical site.

The museum staff includes both civilian historians and military personnel, bringing diverse perspectives to the interpretation of the fort’s complex history. Their passion for accuracy and education comes through in every interaction.

My visit left me with a deeper appreciation for the layered history of Oklahoma and the American West. The story of Geronimo’s final years here represents just one chapter in a much larger narrative about cultural conflict, military expansion, and the transformation of the frontier.

The fort stands as a testament to resilience on all sides. Apache prisoners maintained their identity despite captivity, while the military installation adapted and evolved across generations.

Both stories deserve to be remembered and understood by contemporary visitors.