The Ainu are one of the oldest Indigenous peoples in Northeast Asia, with deep roots in the northern islands and coastal regions of the Pacific Rim. Yet for generations, their history was pushed to the margins – rarely taught, rarely discussed, and often misunderstood.

Their culture once thrived through hunting, fishing, oral tradition, and a spiritual worldview centered on nature. But as modern states expanded into Ainu homelands, laws and policies steadily pressured them to abandon their language, customs, and identity.

Today, that story is changing. Ainu communities are reclaiming what was nearly lost – reviving traditions, restoring pride, and demanding recognition.

This is a closer look at who the Ainu are, what they believe, what they endured, and why their story is finally being heard.

The Ainu Are an Indigenous People

The Ainu are an Indigenous people native to northern Japan and parts of Russia, with deep ties to Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands. Their presence predates modern borders, rooted in seasonal movement, river fisheries, and forested homelands.

You can still trace Ainu place names across valleys, capes, and rivers that anchor stories to the land.

Anthropologists and historians document distinct lifeways, languages, and artistic patterns that set the Ainu apart from neighboring groups. Traditional communities relied on salmon runs, deer, and gathered plants, forming a resilient economy adapted to northern climates.

Longstanding trade connected Ainu with surrounding societies, while maintaining boundaries of custom and ritual.

In Japan’s historical records, Ainu peoples appear as autonomous communities engaging in exchange and occasional conflict. Russian chronicles similarly note Ainu across island corridors, highlighting mobility and diplomacy.

Today, recognition as Indigenous affirms a relationship to territory, culture, and self-determination that survived pressure, loss, and forced change.

“Ainu” Means “Human”

The word Ainu means human in the Ainu language, expressing a core idea of belonging and mutual recognition. Names matter because they define who counts as us and who is other.

When you hear Ainu, you hear a declaration that their community and worldview stand on equal human ground.

Historically, exonyms and official labels tried to fix the Ainu into outsider categories. Yet the self-designation Ainu persisted through oral tradition, ritual speech, and everyday conversation.

It signaled dignity, agency, and continuity during periods when external powers imposed stereotypes.

Language learners today often begin with this simple, resonant word because it centers identity without apology. It also opens a path to understanding how Ainu speech encodes respect for people, spirits, and places.

By using Ainu for human, communities reinforce that culture is lived, not curated, and that recognition starts with how we name ourselves.

They Have a Distinct History and Culture

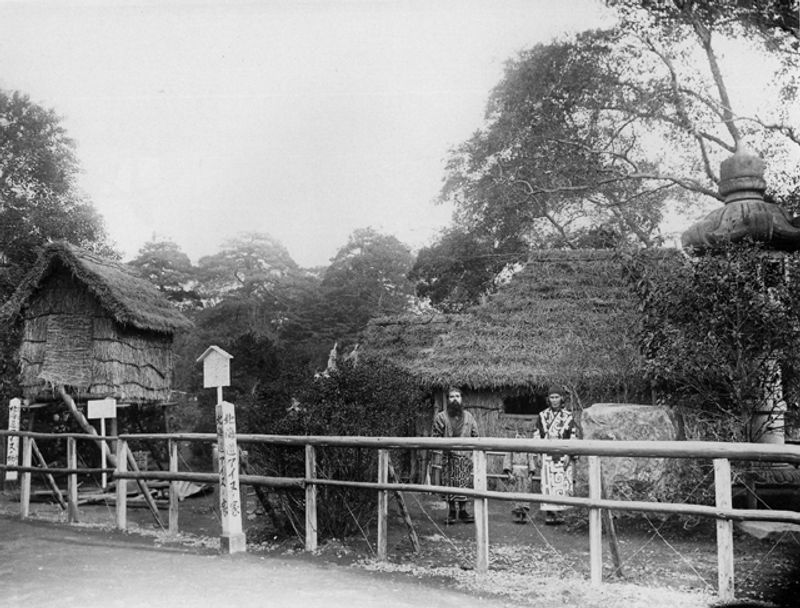

Ainu history unfolds through migration, trade, and adaptation on northern coasts and river systems. Distinctive dress, woodcarving, and ceremonial practice grew from lived relationships with salmon, deer, and forests.

When you see an attus robe or carved pattern, you witness knowledge passed carefully across generations.

Communities organized households around cise dwellings, seasonal work, and reciprocal obligations. Oral literature preserved genealogies, humor, and law, while rituals honored spirits who animate the natural world.

Trade with Wajin Japanese and other neighbors brought iron, rice, and goods, yet Ainu customs sustained separate cultural frames.

Archaeology, chronicles, and oral stories together sketch a picture of resilience under shifting political pressures. Ainu leaders navigated alliances, taxes, and restrictions while defending autonomy.

The result is a cultural record both distinct and dynamic, where continuity exists alongside change, and identity remains anchored in place, practice, and kinship.

Their Language Is Unique and Nearly Lost

The Ainu language is a linguistic isolate with no proven relation to Japanese or most other languages. Historically spoken across Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands, it survived through oral tradition rather than widespread writing.

You will find regional varieties, each shaped by local ecology and contact.

Assimilation policies, schooling in Japanese, and stigma led to a steep decline in native speakers. By the late 20th century, only a handful of fluent elders remained, a critical point for language vitality.

Revival efforts now include classes, dictionaries, media, and songs that bring expression back into daily life.

Scholars document grammar and vocabulary to support teaching, while community groups create children’s programs and cultural camps. Recording elders’ stories helps restore idioms, metaphors, and ceremonial speech.

The goal is not nostalgia but renewed use, so learners can talk, joke, and think in Ainu again.

They May Descend from Ancient Jomon Peoples

Many researchers propose historical links between Ainu populations and the ancient Jomon, hunter-gatherer peoples of the Japanese archipelago. Pottery styles, dental traits, and genetic signals point to deep continuity in the north.

You can think of this as layered ancestry that persisted through later migrations.

The theory emphasizes that rice-farming expansions did not erase earlier lineages everywhere. Instead, northern communities maintained lifeways adapted to forests, coasts, and rivers.

Archaeology shows long durations of settlement where trade and technology varied by region.

Debate continues because evidence is complex and migrations were multiple. New genomic studies refine timelines, suggesting mixture with later arrivals while preserving older components.

The broader picture highlights resilience across millennia, where Ainu heritage connects to enduring Jomon roots without claiming a single, simple origin.

Traditional Ainu Life Was Tied to Nature

Traditional Ainu economies centered on rivers, forests, and coasts, emphasizing salmon fishing, deer hunting, and plant gathering. Seasonal cycles governed work, celebrations, and movement between resource sites.

You can picture households storing dried fish, smoking meat, and weaving bark cloth for clothing.

Knowledge of animal behavior, weather, and watersheds allowed efficient harvests without permanent field agriculture. Canoes navigated rivers and coastal routes for transport and trade.

Tools, baskets, and robes reflected materials gathered sustainably from local environments.

Foodways included salmon, trout, venison, seal, edible roots, and mountain vegetables. Ritual offerings and taboos shaped respectful use of animals and plants.

The result was a practical system suited to northern ecosystems, balancing necessity with cultural values that framed nature as partner rather than backdrop.

Their Spiritual Beliefs Embrace the Spirit World

Ainu spirituality is animistic, recognizing kamuy, or spirit-beings, within animals, plants, tools, and forces like wind and fire. Ceremonies greet visiting spirits, give thanks, and request safe passage for hunters and fishers.

You might notice how offerings and chants align daily life with unseen relationships.

Households maintained hearth rituals, with elders guiding protocol and language. Carved inau prayer sticks, libations, and songs formed a vocabulary of respect.

The goal was not control of nature but reciprocity, where gifts and gratitude balanced taking with giving.

Myths recount how spirits taught humans to live properly and share abundance. In practice, ritual timing followed salmon runs, seasons, and community needs.

These beliefs remain active today in cultural events and private observances that affirm enduring ties between people, land, and the spirit world.

The Bear Ceremony Was Central

Iomante, often called the bear ceremony, held a central place in some Ainu communities. A bear cub was carefully raised, honored as a visiting spirit, then ceremonially sent back to the spirit world.

You see complex emotions in this rite, joining affection, respect, and solemn duty.

Ritual specialists guided songs, offerings, and feasting, with strict protocols that framed the bear as kamuy. Arrows and prayers marked the transition, followed by sharing meat and distributing gifts.

The act symbolized reciprocity, ensuring future well-being and balance between humans and spirits.

Modern presentations explain context and variation across regions, addressing misunderstandings from outside observers. Today, educational programs avoid harm while teaching meaning, symbolism, and history.

The ceremony’s legacy remains a lens to understand Ainu ethics, where gratitude and return define the relationship with powerful beings.

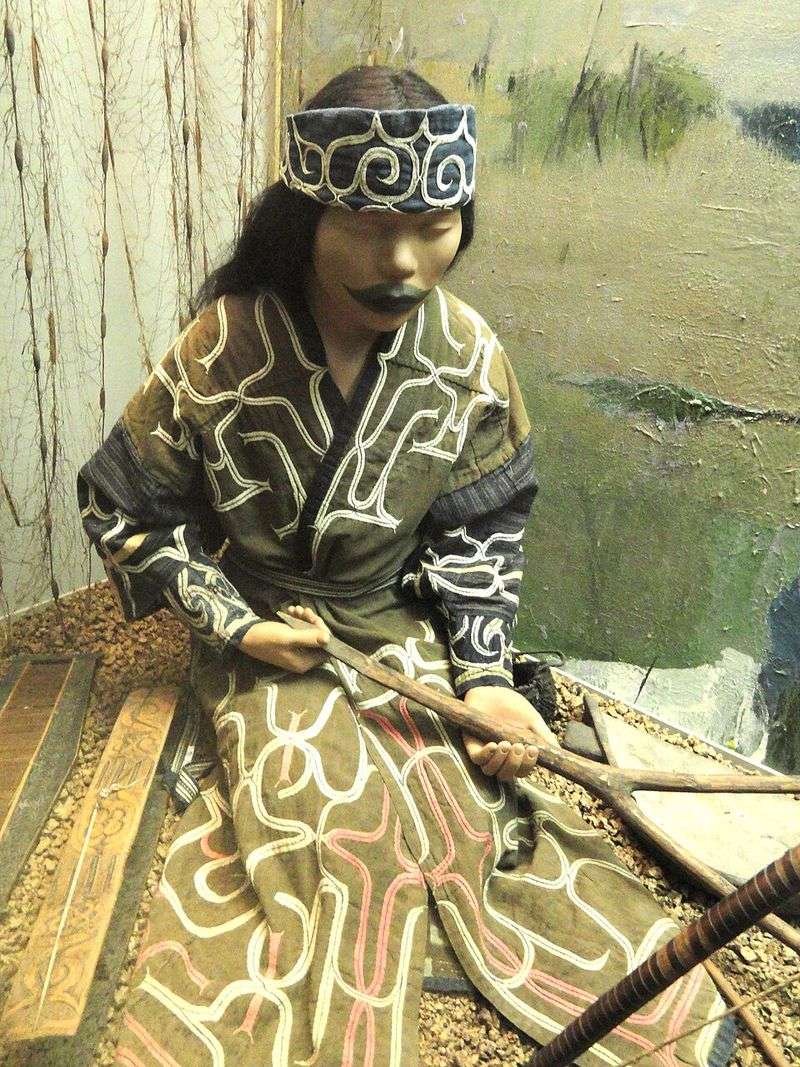

Ainu Clothing and Crafts Were Highly Symbolic

Traditional Ainu clothing, including attus bark-fiber robes and cotton garments with bold applique, displayed protective and symbolic motifs. Patterns along edges were thought to guard openings of the body, reflecting spiritual concerns.

When you trace the stitches, you follow prayers sewn into daily life.

Woodcarving produced utensils, ceremonial sticks, and bear sculptures with flowing lines. Basketry and tools balanced beauty and function, emphasizing texture and durability.

Artistic choices echoed rivers, waves, and plant forms familiar to northern landscapes.

These crafts traveled through trade and influenced regional aesthetics. Museums and community workshops now teach pattern drafting, weaving, and carving to new generations.

Wearing and making traditional designs continues to assert identity, reclaim authorship, and keep cultural knowledge working in the present.

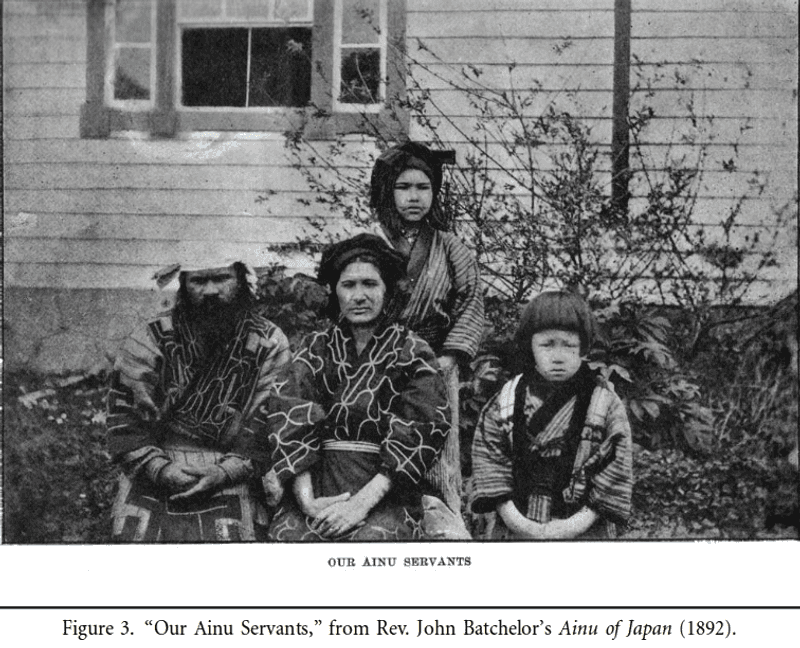

Japanese Expansion Led to Marginalization

From the 13th century onward, Japanese settlers and authorities expanded into Ainu lands, building trade posts and asserting control over resources. This reshaped power relations, limiting local autonomy and redirecting salmon, fur, and labor.

You can track the shift as posts became forts and policies hardened.

By the Meiji era, state-building brought assimilation plans that redefined Ainu as subjects to be modernized. Schooling, land surveys, and regulations curtailed language, dress, and customary practices.

Economic dependence grew as access to traditional territories narrowed.

Historical sources recount conflicts, uprisings, and negotiated peace that often left Ainu communities with fewer rights. The cumulative effect was marginalization through law, market pressures, and social stigma.

These changes set the stage for 20th-century struggles over recognition, reparative measures, and cultural survival.

They Lost Land and Rights

In 1899, the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act categorized Ainu as former aborigines and imposed policies that disrupted livelihoods. Land allocations were small, often inadequate for subsistence, and restricted traditional use.

You can see how paperwork replaced customary rights with conditional ownership.

Hunting and fishing limits, mandatory schooling in Japanese, and bans on cultural practices fragmented community life. Economic hardship followed, pushing families into wage labor while severing ties to resources.

The law’s paternalistic framing treated Ainu as wards rather than partners.

Legal changes across decades slowly modified conditions but rarely restored autonomy. Historical reviews link these frameworks to ongoing disparities in income, education, and health.

Understanding the law’s mechanisms clarifies why land and rights remain central to present-day advocacy and policy reform.

Official Recognition Came Only Recently

After decades of advocacy, Japan recognized the Ainu as an Indigenous people in 2008, followed by a 2019 law supporting cultural promotion. Recognition acknowledged distinct identity, history, and the harms of assimilation.

You can read it as a floor, not a ceiling, for further action.

Policy steps enabled grants, research, and public education, while signaling respect internationally. Yet recognition did not automatically resolve land, resource, or representation issues.

Communities continue to shape proposals that connect rights to lived needs.

Courts and local governments have also weighed in, citing cultural protection and participation. International frameworks, including the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, inform debate.

The timeline shows progress measured in sustained effort, legal detail, and community leadership rather than a single moment.

Cultural Revival Is Underway

Revival efforts strengthen language, arts, and public understanding through schools, workshops, and museums. Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park in Hokkaido serves as a hub for research, performance, and community exchange.

When you visit, you see craft demonstrations, music, and exhibits curated with Ainu voices.

Local organizations teach embroidery, carving, dance, and storytelling to children and adults. Media projects share vocabulary, songs, and history lessons across classrooms and smartphones.

These programs turn interest into practice, making culture accessible rather than distant.

Scholars collaborate with elders to document techniques and narratives while respecting community control. Festivals and conferences connect regional groups and invite broader audiences to learn.

The momentum reflects a forward-looking approach where cultural work builds skills, pride, and opportunities for the next generation.

Ainu People Still Face Challenges

Despite recognition, many Ainu face social stigma, limited representation, and uneven access to resources. Employment and education gaps trace back to historical exclusion and restricted opportunities.

You hear concerns about stereotypes that reduce complex identities to tourist images.

Policy discussions focus on language support, scholarship access, and participation in land and heritage decisions. Community leaders emphasize data transparency, consultation, and funding stability.

Lived experience shows progress where programs align with local priorities.

Media visibility has improved, yet coverage can still overlook diversity within Ainu communities. Building broader understanding requires sustained reporting, school curricula, and respectful storytelling.

Addressing challenges means treating Ainu perspectives as essential, not optional, in shaping future policy and cultural life.

Their Legacy Is Growing Worldwide

International interest in Ainu history and culture has grown across museums, festivals, and academic networks. Exhibitions travel abroad, while collaborations bring Ainu artists and scholars to global stages.

You can encounter Ainu voices in documentaries, podcasts, and university programs.

Digital platforms connect diaspora, learners, and allies who share resources and language materials. Partnerships with Indigenous groups worldwide foster exchange on rights, education, and cultural economies.

These links highlight common experiences of survival, advocacy, and renewal.

As visibility expands, careful curation and community leadership remain vital to avoid appropriation and misrepresentation. The hope is informed attention that supports authentic practice and legal progress.

A growing legacy rests on listening, learning, and ensuring Ainu communities guide how their story is told.