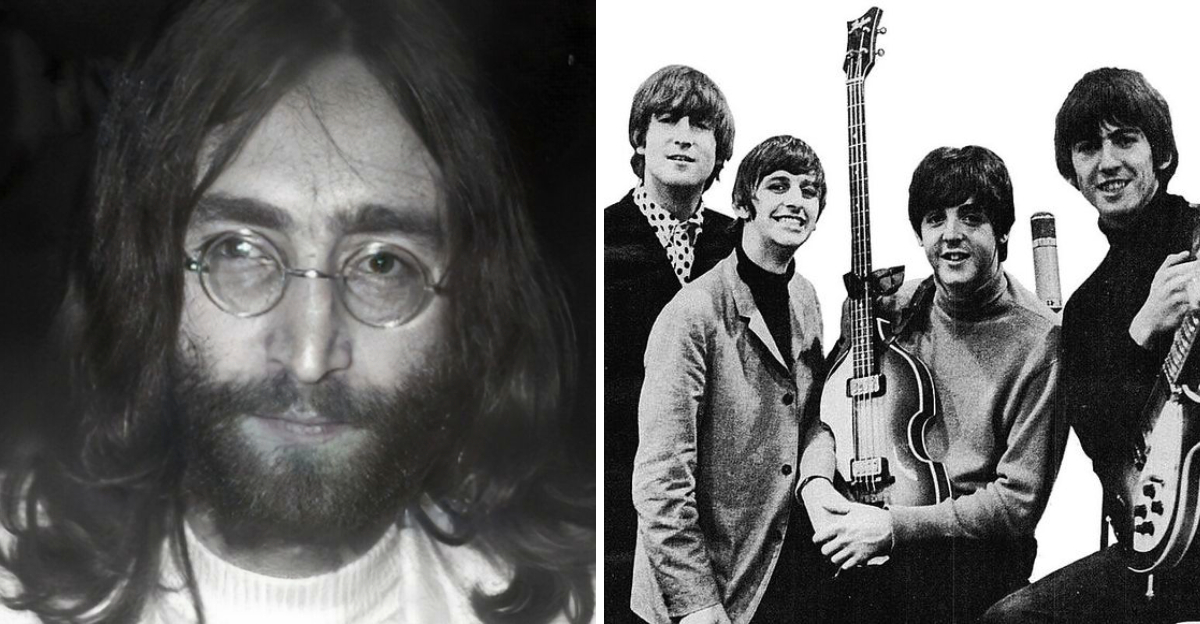

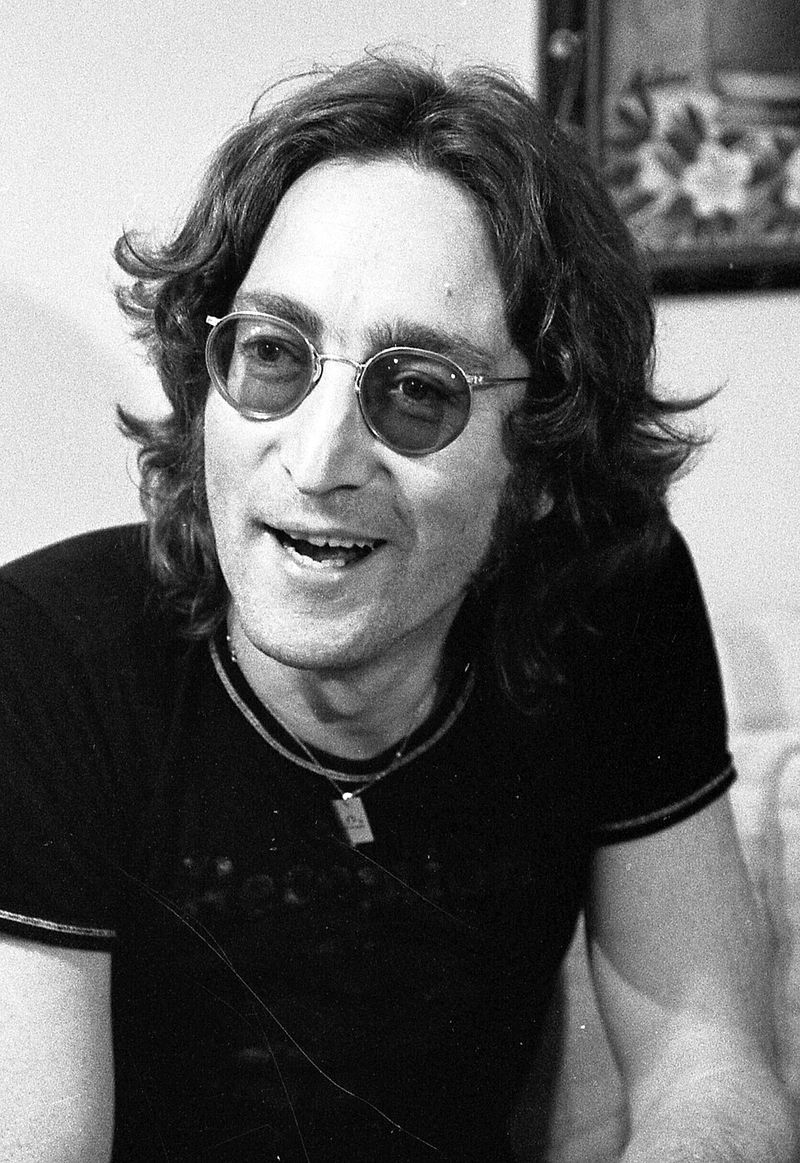

John Lennon was famously candid about his work, and that honesty extended to several Beatles songs he later downplayed or criticized. This list gathers tracks he openly dismissed for their lyrics, simplicity, studio grind, or lack of personal connection.

You will find quick context, direct quotes where relevant, and how his views evolved over time. It is a clear look at the gap between public favorites and the artist’s own standards.

1. Run for Your Life

Run for Your Life closed Rubber Soul, yet Lennon later called it his least favorite Beatles song. He particularly disliked the threatening lyric lifted from an Elvis Presley line, saying it felt careless and mean.

In interviews, he said he wrote it quickly and regretted the tone, placing it among the few he would rather forget.

The song’s brisk rockabilly feel and sharp guitar lines mask lyrics that have not aged well. Lennon’s critique centered on lyrical intent, not musicianship, and he acknowledged the band still performed it tightly.

Fans often note its energy, but Lennon’s own standard for honesty and empathy made it a sore point.

Context matters here. Rubber Soul marked a turn toward deeper writing, yet this track looked backward.

Lennon later preferred songs that revealed vulnerability or insight, and Run for Your Life felt like a posture. His retrospective view helps explain why it rarely appears in celebratory retrospectives.

2. It’s Only Love

It’s Only Love was one Lennon said he really hated, calling the lyrics terrible. He admitted the melody had charm but felt the words were thin and repetitive.

Recorded for Help!, it shows a transitional writer still reaching for sharper language and more layered feeling, something he later achieved on tracks like In My Life.

Listeners often enjoy the gentle guitar and Lennon’s warm vocal. Still, he was harsh on himself, treating this as an example of rushing to meet deadlines.

In hindsight, his critique underscores how rapidly his standards rose between 1965 and the more introspective, crafted work that followed.

The band’s tight arrangement cannot mask Lennon’s own dissatisfaction. He tended to judge songs by lyrical depth, and this one fell short for him.

While not a failure musically, he did not stand behind its sentiment. His candor makes it a revealing footnote in his evolving approach to songwriting.

3. Maxwell’s Silver Hammer

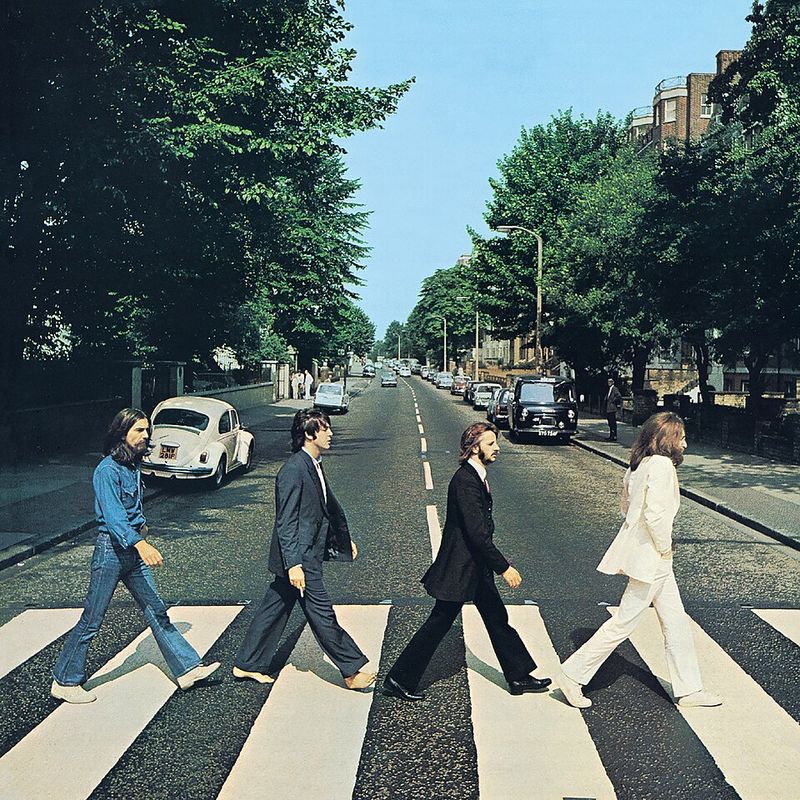

Maxwell’s Silver Hammer, primarily a McCartney composition, drew open disdain from Lennon. He bluntly said I hate it and resented the endless studio takes that consumed time during tense 1969 sessions.

The song’s vaudeville bounce and darkly comic lyrics clashed with his preference for directness and emotional truth.

Accounts from the sessions describe mounting frustration as the band repeated overdubs to achieve Paul’s polished vision. Lennon felt the whimsy was out of step with the band’s mood.

Even admirers concede it tested patience, and the studio grind became part of its legacy, coloring how bandmates recalled the track.

As a recording artifact, it is meticulously arranged. Yet Lennon’s criticism highlights creative divergence near the end of the Beatles era.

His dislike was not only stylistic, but also about process and priorities. The song now stands as a case study in how differing artistic aims can strain a group.

4. Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da

Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da became a lightning rod for Lennon’s frustration with Paul’s playful pop instincts. He mocked it in the studio and reportedly banged out a harder piano take to speed things along.

The catchy ska-flavored groove delighted many listeners, but Lennon felt it was frivolous and overworked.

Session stories suggest tension as multiple versions were attempted. Lennon’s critique was less about craft and more about taste.

He preferred raw feeling to chirpy optimism, and this track’s breezy lyrics did not align with his sensibilities. Despite that, it became a crowd favorite, underscoring the Beatles’ stylistic range.

In retrospect, the song represents the band’s push-pull dynamic. Paul’s melody-driven pop met John’s edge, sometimes uneasily.

Lennon’s disdain reflects the broader White Album turbulence, where individual visions often clashed. The contrast helps explain why this sunny track remains divisive among fans and historians.

5. Hello, Goodbye

Hello, Goodbye topped charts, yet Lennon dismissed it as lightweight. He felt the lyric played with simple opposites without saying much, contrasting it with his preference for bolder statements.

While he acknowledged Paul’s knack for hooks, he did not rate this one as meaningful art, seeing it as surface-level pop craftsmanship.

The recording is sleek and rhythmically buoyant, supported by harmonies and strings. Listeners appreciate its immediate clarity, which also underpins Lennon’s critique.

He often valued ambiguity and bite, and the song’s simplicity read as safe. Its success highlighted the duo’s complementary strengths and creative differences.

Placed within 1967’s experimental context, it sounds conservative next to b-sides Lennon favored. He publicly noted its thin idea, even as it sold massively.

That split between impact and intention epitomizes their partnership. The song endures, but Lennon’s comments frame it as catchy rather than consequential.

6. Let It Be

Let It Be was authored by McCartney, and Lennon publicly disavowed involvement in writing it. He suggested it could have been a Wings song, implying he did not view it as a quintessential Beatles statement.

Though he respected its craft, he felt the sentiment was more Paul’s domain than a Lennon-McCartney blend.

The song’s gospel-tinged arrangement and message of acceptance resonated widely. Lennon’s critique centered on authorship and identity, not performance.

He tended to separate the band’s collective voice from individual expressions, and here he saw a solo sensibility cloaked in the Beatles brand, especially amid late-era tensions.

Over time, Let It Be became a cultural touchstone. Lennon’s distance remains part of its backstory, revealing divergent priorities in 1969 and 1970.

His comments underscore the fractured creative unity near the end. Admirers still find solace in it, even as Lennon’s appraisal reframes its place in the catalog.

7. All You Need Is Love

All You Need Is Love debuted via a global broadcast and became an anthem, yet Lennon later called it simplistic and cliché. He felt the message lacked the nuance he sought in later writing.

While he enjoyed the moment’s scale, he criticized its broad strokes, saying it did not represent deep artistic effort.

Musically, the track weaves quotes and a singalong chorus, designed for instant grasp. That design is exactly what Lennon questioned in hindsight.

He came to prefer complexity or vulnerability over slogans. Still, the song effectively captured 1967’s mood, and its utility may explain its lasting recognition.

Lennon’s critique invites a balanced view. The piece worked as an event and as pop communication, but not as his ideal of probing art.

Appreciating both frames clarifies how a cultural anthem can succeed on one level while feeling thin to its author. The dual legacy remains instructive.

8. Help!

Help! is iconic, yet Lennon said it was written in a hurry and that he was not proud of its simplicity compared to later work. He later admitted the lyric masked real anxiety during intense fame.

The pop packaging, fast tempo, and tight harmonies made the plea sound lighter than he actually felt.

His critique was not a total dismissal. He recognized the honest core but wished for more depth in execution.

As his writing matured, he gravitated toward frank confessional tones, and Help! felt like an early draft of that approach, constrained by commercial and production demands of 1965.

Still, the track’s directness resonated with millions. Lennon’s hindsight reframes it as both successful and under-realized.

That tension shows how artists reassess their catalog as personal standards evolve. Help! remains a milestone that revealed vulnerability, even if Lennon judged it against his later bar for candor.

9. I Should Have Known Better

I Should Have Known Better dates to the A Hard Day’s Night period, featuring Lennon’s harmonica and brisk charm. He later implied it did not mean much to him, viewing it as a functional pop track rather than a statement.

The song’s lightweight lyric and by-the-numbers structure felt routine in hindsight.

In 1964, speed and momentum shaped the band’s output, and this fit the brief. Fans enjoy its immediacy, but Lennon’s later standards prized depth over formula.

His comment situates the piece as part of the early craft phase, when efficiency often overshadowed introspection and experimental ambition.

The recording still sparkles with energy and precision. Yet for Lennon, it lacked personal stake.

He often favored songs that exposed vulnerability or pushed form, and this one did neither. Its legacy now reads as a snapshot of a hardworking band meeting demand, not a track he cherished.

10. Hold Me Tight

Hold Me Tight was dismissed by Lennon as a lesser effort that neither he nor McCartney cared much about. Originally attempted for Please Please Me and later issued on With the Beatles, it reflects their early assembly-line pace.

The performance is spirited, but the song’s hook and lyric struck Lennon as generic.

He often contrasted such tracks with later material that carried emotional weight. Hold Me Tight, in his view, ticked boxes without saying anything new.

The band moved quickly in 1963, and this number shows both their tight musicianship and the limits of writing to schedule instead of inspiration.

Listeners may still enjoy its beat-group charm. Lennon’s critique, though, helps categorize it as competent rather than essential.

Framed this way, the song offers a useful baseline for judging growth. It illuminates how rapidly the Beatles evolved from energetic fillers to boundary-pushing, personally resonant work.