Greece isn’t just a beautiful vacation spot with sunny beaches and delicious food. Beneath its modern surface lies a treasure trove of ancient wonders that stretch back hundreds of thousands of years.

From prehistoric fossils hidden in coastal caves to magnificent temples that once hosted the Olympic Games, these relics tell the story of human civilization itself. Get ready to journey through time and discover the 17 oldest things in Greece that prove this country has been at the center of human history since the very beginning.

Pavlopetri — World’s Oldest Submerged City (~5,000 Years Old)

Imagine walking through streets that haven’t seen sunlight in 5,000 years. Off the coast of Laconia, beneath the sparkling blue waters of the Mediterranean, lies Pavlopetri—the world’s oldest known submerged city.

This isn’t just a few scattered stones on the seafloor. It’s a complete Bronze Age town with recognizable streets, buildings, courtyards, and even tombs.

Divers exploring the site can see the entire urban layout spread across the sandy bottom. The preservation is so remarkable that archaeologists can study how Bronze Age Greeks organized their communities.

Houses stand in organized rows, public spaces occupy central areas, and the whole settlement reveals sophisticated urban planning from roughly 3000 BC.

The city likely sank due to earthquakes, which are common in this seismically active region. Water and sediment protected the ruins from erosion and human interference that destroyed many land-based sites.

Researchers use special underwater mapping technology to document every structure without disturbing the fragile remains. Pavlopetri offers an unparalleled snapshot of daily life in prehistoric Greece, frozen in time beneath the waves.

Walking through modern Greek towns, it’s humbling to think that equally complex communities existed five millennia ago, now resting silently underwater.

Dokos Shipwreck — Oldest Known Shipwreck (c. 2700–2200 BC)

The seafloor near the tiny islet of Dokos guards a watery grave that’s been undisturbed for over 4,000 years. This shipwreck represents the oldest documented maritime disaster in human history, dating somewhere between 2700 and 2200 BC during the Early Helladic period.

The vessel itself has long since rotted away, but its cargo remains scattered across the sandy bottom.

Hundreds of clay vases, storage jars, and ceramic containers lie where they fell when the ship went down. These weren’t just random pots—they were trade goods being transported across the Aegean Sea.

Their presence proves that ancient Greeks were accomplished sailors who risked dangerous voyages to exchange products between islands and coastal settlements.

Archaeologists carefully cataloged each artifact, noting shapes, sizes, and decorative patterns that reveal manufacturing techniques from the Bronze Age. The pottery styles help researchers understand trade networks and cultural connections between different regions.

Some vessels still contained traces of their original contents, offering clues about what ancient merchants valued most. The Dokos shipwreck isn’t just a tragedy frozen in time—it’s evidence that maritime commerce, with all its risks and rewards, has connected Greek communities for millennia.

Every amphora tells a story of ambition, craftsmanship, and the eternal human drive to explore beyond the horizon.

Theatre of Thorikos — Oldest Known Greek Theatre (c. 525–480 BC)

Forget everything you think you know about Greek theatre design. In the ancient mining town of Thorikos in Attica, archaeologists found a performance space that breaks all the rules.

Built between approximately 525 and 480 BC, this theatre claims the title of the world’s oldest surviving theatrical venue. What makes it truly unusual is its shape—instead of the familiar semicircular design, the Theatre of Thorikos is surprisingly elongated.

This odd shape suggests that theatrical architecture was still evolving during the Archaic period. Builders were experimenting with different layouts before settling on the classic semicircle that would define Greek theatre for centuries.

The theatre served the mining community of Thorikos, where workers extracted silver and lead from nearby mountains.

Stone seats cascade down the hillside, facing a performance area where ancient actors once brought myths and stories to life. The acoustics, while not as refined as later theatres, still allowed audiences to hear performers clearly.

Visitors today can sit on the same worn stones where Greek miners relaxed after long days underground, watching plays that mixed entertainment with religious ritual. The Theatre of Thorikos reminds us that even revolutionary art forms like drama had humble, imperfect beginnings.

Those early performances in this strangely shaped venue would eventually inspire theatrical traditions that continue worldwide.

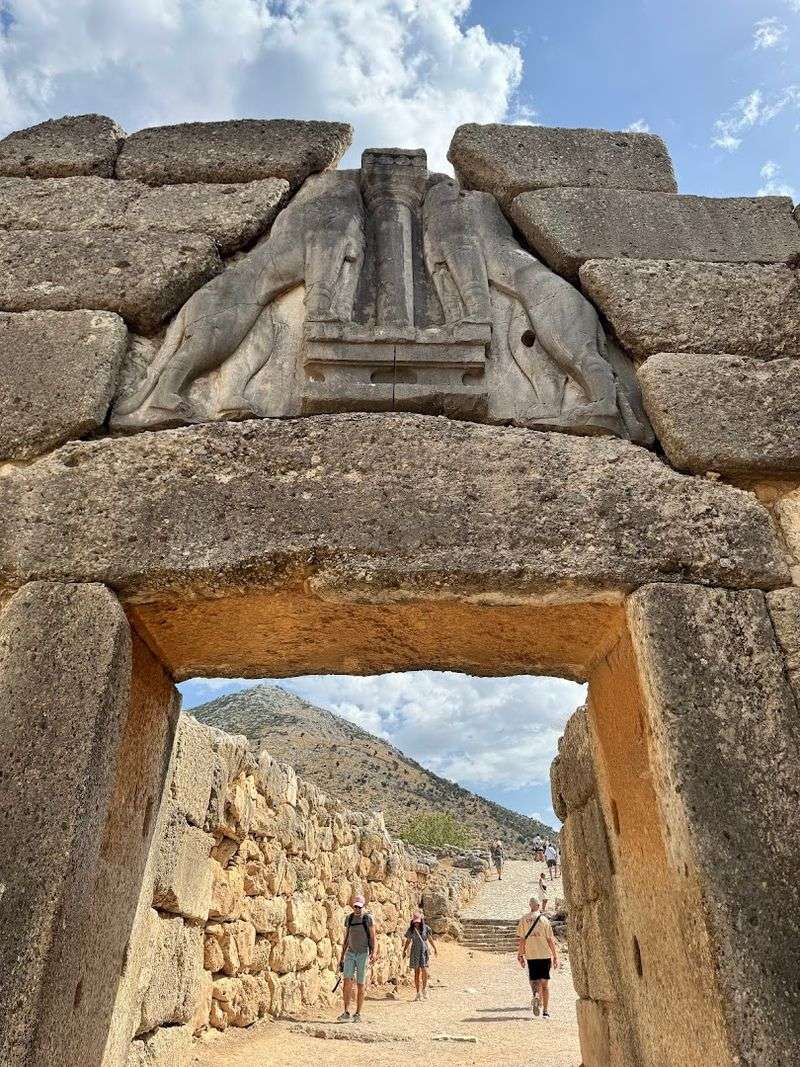

Mycenae — Bronze Age Citadel (c. 1600–1100 BC)

Massive stone walls rise from a hilltop in the Peloponnese, each block so enormous that later Greeks believed only mythical giants could have built them. Welcome to Mycenae, the fortified palace complex that dominated Bronze Age Greece from approximately 1600 to 1100 BC.

This wasn’t just a castle—it was the power center of an entire civilization that gave us legends like Agamemnon and the Trojan War.

The famous Lion Gate still guards the entrance, with its carved lions standing sentinel after more than 3,000 years. Walking through this gateway feels like stepping into Homer’s epics, where warrior kings ruled from stone strongholds and treasures filled underground tombs.

The walls themselves stretch impressively thick, built from carefully fitted stones that have survived earthquakes, invasions, and millennia of weathering.

Inside the citadel, archaeologists uncovered royal graves filled with gold masks, weapons, and jewelry that revealed the wealth and military prowess of Mycenaean rulers. Heinrich Schliemann, the famous excavator, believed he’d found the tomb of Agamemnon himself, though modern scholars are more cautious about such claims.

Regardless of which specific kings lived here, Mycenae represents one of Greece’s earliest complex civilizations. The engineering skill required to construct these cyclopean walls demonstrates sophisticated organization and architectural knowledge that predated classical Greece by centuries.

Knossos — Minoan Palace (c. 2000 BC)

On the island of Crete stands a palace so complex and maze-like that it inspired the legend of the Minotaur’s labyrinth. Knossos served as the ceremonial and political heart of the Minoan civilization around 2000 BC, centuries before classical Greek culture emerged.

The palace wasn’t just a royal residence—it was a sprawling complex of rooms, courtyards, storage areas, and religious spaces that housed an entire administrative apparatus.

Vibrant frescoes still decorate some walls, showing dolphins, bulls, and elegant figures in elaborate costumes. These paintings reveal a sophisticated society that valued art, religious ritual, and possibly even bull-leaping ceremonies.

The Minoans developed Europe’s first advanced civilization, complete with indoor plumbing, multi-story buildings, and extensive trade networks across the Mediterranean.

British archaeologist Arthur Evans excavated and controversially reconstructed portions of Knossos in the early 20th century. While his reconstructions help visitors visualize the palace’s former glory, scholars debate their historical accuracy.

The original structure featured hundreds of interconnected rooms that could easily confuse visitors—hence the labyrinth association. Storage rooms contained massive clay jars called pithoi that held olive oil, wine, and grain, demonstrating the palace’s role as an economic center.

Knossos shows that Greek civilization didn’t begin with Athens or Sparta—it started on Crete with the mysterious Minoans and their breathtaking palaces.

Ancient Olympia — Birthplace of the Olympic Games (c. 776 BC)

Every four years, athletes from around the world gather to compete in the Olympics, continuing a tradition that began in a peaceful valley in western Greece. The sanctuary of Ancient Olympia hosted the first recorded Olympic Games in 776 BC, though athletic competitions likely occurred there even earlier.

This wasn’t just about sports—the Games were a religious festival honoring Zeus, the king of the gods.

Ruins of temples, training facilities, and the original stadium still mark the landscape. Athletes competed naked in events like running, wrestling, boxing, and chariot racing while thousands of spectators cheered from earthen banks.

Winners received olive wreaths rather than gold medals, but the glory they earned lasted a lifetime. Cities declared truces during the Games, allowing safe passage for competitors and spectators traveling from across the Greek world.

The Temple of Zeus once housed one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—a massive gold and ivory statue of the god seated on his throne. Though the statue is long gone, its foundation remains, helping us imagine its former magnificence.

The Olympic flame that begins each modern Games is still lit here using a parabolic mirror to focus sunlight, connecting today’s athletes with their ancient predecessors. Ancient Olympia reminds us that sports have united people across cultures for thousands of years.

Delphi — Oracle Site (c. 1400–1200 BC)

Perched on the slopes of Mount Parnassus, a sacred site once drew pilgrims from across the known world seeking answers about their futures. Delphi, home to the famous Oracle of Apollo, was considered the omphalos—the navel or center of the entire world.

From approximately 1400 BC through the Roman period, priestesses called Pythia delivered cryptic prophecies that influenced military campaigns, political decisions, and personal choices.

The Temple of Apollo dominated the sanctuary, its columns rising dramatically against the mountainside. Pilgrims climbed the Sacred Way, passing treasuries built by various city-states to house their offerings to the god.

The theatre and stadium hosted musical competitions and athletic games, making Delphi a cultural center as well as a religious one.

The oracle’s prophecies were famously ambiguous, open to multiple interpretations that protected the priestess’s reputation regardless of outcomes. Kings and commoners alike sought her wisdom, believing Apollo spoke through her while she sat on a tripod above a chasm releasing intoxicating vapors.

Modern geologists have found evidence of hydrocarbon gases seeping from faults beneath the temple, possibly explaining the Pythia’s trance-like state. Whether divinely inspired or chemically induced, the Oracle of Delphi wielded enormous influence over ancient Greek affairs.

The site’s dramatic location and mysterious atmosphere still captivate visitors who climb the same paths ancient seekers once trod.

Acropolis of Athens — Classical Marvel (5th century BC)

A rocky outcrop rises above modern Athens, crowned with marble temples that have defined Western civilization for 2,500 years. The Acropolis, dominated by the magnificent Parthenon, represents the pinnacle of classical Greek achievement.

Built during the 5th century BC under the leadership of Pericles, these structures celebrated Athens’ victory over Persia and embodied the city’s democratic ideals, artistic excellence, and philosophical sophistication.

The Parthenon itself served as a temple to Athena, the city’s patron goddess. Its architects Ictinus and Callicrates incorporated subtle curves and optical refinements that make the building appear perfectly straight despite being constructed entirely from marble blocks.

Inside once stood a massive gold and ivory statue of Athena, though it was lost centuries ago.

Other structures on the Acropolis include the Erechtheion with its famous Caryatid columns (sculpted female figures serving as architectural supports) and the Temple of Athena Nike commemorating military victories. The Propylaea served as the monumental gateway, announcing to visitors that they were entering sacred space.

Despite damage from wars, explosions, and pollution, the Acropolis remains Athens’ most iconic landmark. Restoration work continues using ancient techniques and original marble from the same quarries used 2,500 years ago.

Standing atop the Acropolis, you can see how classical ideals of beauty, proportion, and harmony in architecture continue influencing buildings worldwide.

Ancient Agora — Civic Heart of Athens (6th century BC)

Below the Acropolis spreads a field of ancient ruins that once buzzed with the conversations that shaped Western thought. The Ancient Agora of Athens served as the city’s civic heart from the 6th century BC onward, combining marketplace, political assembly, and social gathering place in one bustling complex.

This is where democracy was practiced, philosophy was debated, and daily commerce unfolded under the Mediterranean sun.

Socrates walked these paths questioning citizens about virtue and knowledge. Merchants hawked goods from stalls while politicians argued policy in the Bouleuterion (council house).

The Stoa of Attalos, a long covered colonnade, provided shade for shoppers and philosophers alike—its modern reconstruction helps visitors imagine the Agora’s original appearance.

The well-preserved Temple of Hephaestus overlooks the site, dedicated to the god of craftsmen and metalworkers. Its columns and pediments remain largely intact, offering one of the best examples of classical Greek temple architecture.

Archaeologists have uncovered countless artifacts here: pottery shards, coins, voting tokens, and everyday objects that illuminate how ordinary Athenians lived. The Agora wasn’t just for elites—it was where all citizens, regardless of wealth, could participate in civic life.

Walking through these ruins, you’re literally following in the footsteps of history’s most influential thinkers, whose ideas about government, ethics, and reason still guide modern societies.

Temple of Poseidon at Sounion (c. 444–440 BC)

Atop windswept cliffs where the Aegean Sea stretches endlessly toward the horizon, marble columns stand in eternal tribute to the god of the oceans. The Temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion dates to approximately 444-440 BC, built during Athens’ Golden Age when the city-state dominated maritime trade and naval power.

Sailors passing this promontory would make offerings to Poseidon, praying for safe voyages across unpredictable waters.

The temple’s location is breathtaking—perched on a cliff 200 feet above the sea, with panoramic views that seem to merge sky and water. Ancient architects chose this spot deliberately, placing the sea god’s sanctuary at the very edge of land.

Of the original 34 columns, 16 still stand, their white marble glowing golden during sunset in one of Greece’s most photographed scenes.

The temple was built from local marble using the Doric order, the simplest and most masculine of Greek architectural styles. Unlike the Parthenon’s refined details, this temple’s proportions are slightly stockier, perhaps to withstand the fierce winds that whip across the cape.

Lord Byron famously carved his name on one of the columns during his 19th-century visit—an act of vandalism that would horrify modern conservationists but reflected the Romantic era’s fascination with classical ruins. Visiting Sounion at sunset remains a pilgrimage for travelers seeking to connect with ancient maritime culture and natural beauty.

Epidaurus Theatre — Acoustic Wonder (4th century BC)

Drop a coin on the stage and hear it clearly from the top row, 55 meters away. The ancient theatre of Epidaurus, built in the 4th century BC, demonstrates acoustic engineering so sophisticated that modern architects still study its design.

This isn’t just the best-preserved ancient theatre in Greece—it’s an acoustic marvel that allows 14,000 spectators to hear performers without any amplification whatsoever.

The theatre’s perfect symmetry and mathematical proportions create its remarkable sound properties. Limestone seats arranged in precise tiers filter out low-frequency background noise while amplifying the higher frequencies of human voices.

The stage’s design and the seating area’s angle work together to project sound upward and outward with crystal clarity.

Epidaurus wasn’t built primarily for entertainment—it was part of a healing sanctuary dedicated to Asclepius, the god of medicine. Ancient Greeks believed that watching dramatic performances had therapeutic value, helping cure both physical and mental ailments.

The theatre hosted plays during religious festivals, with actors wearing masks to project different characters and emotions. Today, the theatre still hosts performances during the annual Epidaurus Festival, allowing modern audiences to experience ancient drama in its original setting.

Sitting in these stone seats under the stars, watching Greek tragedies unfold with perfect acoustics, connects us directly to theatrical traditions that began over 2,300 years ago in this very spot.

Phaistos — Bronze Age Minoan Palace (c. 2000 BC)

On a hilltop overlooking Crete’s Mesara Plain sits another architectural wonder from the mysterious Minoan civilization. Phaistos, like its more famous cousin Knossos, flourished around 2000 BC as a major Bronze Age palace complex.

The site offers spectacular views of Mount Ida and the surrounding countryside, chosen deliberately to project power and control over the fertile valley below.

The palace featured multiple courtyards, elaborate storerooms, and residential quarters arranged around a central courtyard following typical Minoan design. Advanced drainage systems and sophisticated construction techniques reveal the Minoans’ engineering expertise.

Unlike Knossos, Phaistos hasn’t been extensively reconstructed, allowing visitors to see authentic ruins without modern additions.

The palace’s most famous discovery is the Phaistos Disc, a clay disk covered with mysterious stamped symbols that no one has successfully deciphered. This enigmatic artifact represents one of the world’s oldest examples of movable type printing, with each symbol pressed into wet clay using individual stamps.

The disc’s meaning remains one of archaeology’s great unsolved puzzles—is it a prayer, a calendar, a story, or something else entirely? Phaistos demonstrates that Minoan civilization extended far beyond Knossos, with multiple palace centers controlling different regions of Crete.

The ruins speak to a sophisticated Bronze Age culture that valued art, architecture, and administration centuries before classical Greek culture emerged.

Ancient Corinth — Strategic City (c. 8th century BC)

Strategically positioned between two seas, Ancient Corinth controlled one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in the Greek world. Founded around the 8th century BC, this powerful city-state grew wealthy from maritime trade and port taxes.

Ships traveling between the Aegean and Ionian Seas had to either sail around the dangerous Peloponnese or pay to have their cargo transported across the narrow Isthmus of Corinth, filling the city’s coffers.

Seven standing columns from the Temple of Apollo remain as Corinth’s most iconic ruins, their weathered limestone dating to the 6th century BC. The ancient city sprawled across terraces below the towering Acrocorinth fortress, which provided protection and a commanding view of the isthmus.

The Agora (marketplace) featured elaborate fountains, temples, and administrative buildings reflecting Corinth’s commercial importance.

Corinth was also notorious in antiquity for its cosmopolitan atmosphere and the Temple of Aphrodite, where religious prostitution allegedly occurred—though modern scholars debate this claim’s accuracy. The city’s wealth attracted artists, merchants, and immigrants from across the Mediterranean.

Saint Paul later preached here, and his letters to the Corinthians became part of the New Testament. Earthquakes repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt Corinth throughout history, with ruins spanning Greek, Roman, and Byzantine periods layered atop each other.

This archaeological palimpsest reveals how strategic location can sustain urban centers for thousands of years despite natural disasters.

Eleusis — Mysteries Sanctuary (c. 1500 BC)

Just outside Athens lies a sanctuary where ancient Greeks celebrated the most secretive religious rites in their culture. Eleusis hosted the famous Eleusinian Mysteries, initiation ceremonies honoring Demeter (goddess of agriculture) and her daughter Persephone that dated back to at least 1500 BC.

These weren’t public festivals—they were closely guarded secrets that initiates swore never to reveal upon pain of death.

The mysteries reenacted the myth of Persephone’s abduction by Hades and her mother’s grief, which explained the seasons’ cycle. Initiates underwent elaborate purification rituals, fasted, drank a special potion called kykeon, and witnessed secret revelations in the Telesterion, a massive hall that could accommodate thousands.

What exactly they experienced remains unknown since participants kept their vows of secrecy remarkably well.

Ancient writers hint that initiates gained comfort about death and the afterlife through their mystical experiences at Eleusis. Famous participants included philosophers, politicians, and emperors—Cicero claimed the mysteries gave Athens its greatest gift to humanity.

The sanctuary operated for nearly 2,000 years until Christian Roman emperors closed it in the 4th century AD. Ruins of the Telesterion, the Sacred Way, and various temples remain, though the mysteries themselves died with their last initiates.

Eleusis reminds us that ancient Greek religion involved far more than the familiar Olympic gods—it included profound spiritual experiences that transformed participants’ understanding of life and death.

Vergina (Aigai) Palace — Macedonian Royal Capital (c. 4th century BC)

Beneath a modern protective structure in northern Greece lie the remains of a palace where one of history’s greatest conquerors began his reign. The Palace of Aigai at Vergina served as the ceremonial capital of ancient Macedonia during the 4th century BC.

This is where Alexander the Great was proclaimed king in 336 BC, following his father Philip II’s assassination. Recent restoration has returned the palace to something approaching its former grandeur.

The royal tombs discovered here in 1977 caused archaeological sensation. One tomb contained remains and artifacts believed to belong to Philip II himself, including a golden larnax (chest) decorated with the Macedonian sun symbol.

The tomb’s treasures—armor, weapons, golden wreaths, and exquisite artwork—reveal Macedonian royal wealth and artistic sophistication that rivaled any Greek city-state.

The palace complex featured colonnaded courtyards, throne rooms, and ceremonial spaces where Macedonian kings entertained guests and conducted state business. Its size and elaboration demonstrated Macedonia’s transformation from a semi-barbarous kingdom into a dominant power that would eventually conquer the entire Persian Empire.

Visiting Vergina connects you directly to the Macedonian dynasty that changed world history. The golden artifacts gleaming in museum cases once adorned warriors and kings whose ambitions reshaped the ancient world, spreading Greek culture from Egypt to India through Alexander’s unprecedented conquests.

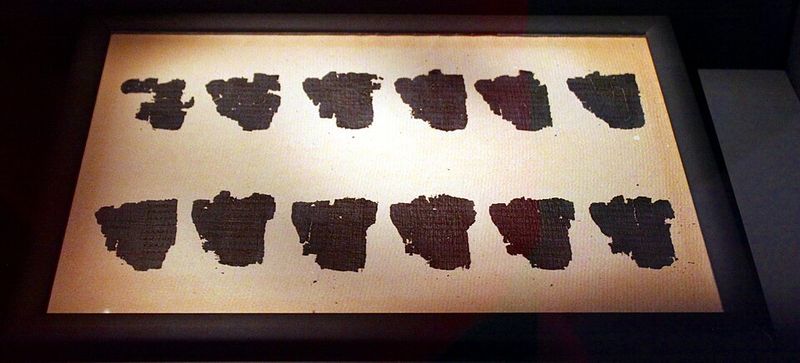

Derveni Papyrus — Oldest European Manuscript (c. 340 BC)

Charred and fragile, a rolled papyrus discovered in a tomb near Thessaloniki holds the distinction of being Europe’s oldest surviving manuscript. The Derveni papyrus dates to approximately 340 BC and survived only because fire carbonized it during the funeral pyre, ironically preserving what would normally have decayed completely.

This precious document contains philosophical commentary on ancient poetry, offering a rare glimpse into Greek intellectual thought during the Classical period.

The text discusses Orphic religious beliefs and interprets allegorically a poem about the gods’ origins and relationships. The author quotes earlier poetry while adding sophisticated philosophical analysis, showing how educated Greeks approached religious texts.

The writing style and argumentation reveal advanced literacy and abstract thinking that characterized Greek intellectual culture.

Scholars painstakingly unrolled and deciphered the brittle papyrus using specialized conservation techniques. Many sections remain damaged or illegible, but enough survives to make it an invaluable primary source.

Before this discovery, the oldest European manuscripts dated to the medieval period, leaving a thousand-year gap in the written record. The Derveni papyrus fills part of that void, proving that book culture existed in ancient Greece beyond what we knew from later copies.

The manuscript reminds us how much ancient literature has been lost—for every text that survived, hundreds or thousands perished through fire, decay, or deliberate destruction. This single charred scroll represents countless philosophical treatises, poems, and commentaries that once circulated in the ancient Greek world.

National Archaeological Museum Collections — Prehistory to Classical

If you want to understand the full sweep of Greek history, one building in Athens contains the most comprehensive collection anywhere. The National Archaeological Museum houses over 11,000 artifacts spanning from prehistoric times through the classical period and beyond.

Walking through its galleries is like traveling through time, from Stone Age tools to Roman copies of Greek masterpieces.

The museum’s prehistoric collection includes Mycenaean gold, Cycladic figurines, and Minoan frescoes that predate classical Greece by over a thousand years. The sculpture galleries display iconic works like the bronze Poseidon (or Zeus) statue recovered from the sea, frozen mid-throw with perfect anatomical detail.

The Antikythera mechanism, an ancient astronomical calculator, demonstrates Greek technological sophistication that wouldn’t be matched for centuries.

Pottery collections show the evolution of Greek ceramic art from simple geometric patterns to elaborate red-figure vases depicting mythological scenes. Jewelry, weapons, coins, and everyday objects illuminate how ordinary Greeks lived, worked, and worshipped.

Each artifact tells multiple stories—about the individual who made or used it, the society that valued it, and the archaeologists who preserved it for future generations.

The museum faces the ongoing challenge of displaying such vast holdings while keeping exhibits engaging and educational. New technologies like digital reconstructions help visitors visualize how fragmentary objects once appeared.

For anyone seriously interested in Greek history, this museum is essential—it’s where material culture brings ancient texts and myths to tangible life.