The Canadian Arctic, once protected by extreme cold and ice, now faces an unprecedented threat. Climate change has warmed this region four times faster than the global average, creating new pathways for non-native species to enter these pristine ecosystems. Scientists recently detected DNA from a non-native barnacle in Arctic waters – the first confirmed molecular evidence of an invasive marine species in Arctic Canada, signaling that the natural barriers keeping these ecosystems isolated may be crumbling.

The First Invader: Bay Barnacle Makes History

Scientists made a startling discovery that changes everything we know about Arctic ecosystems. Using cutting-edge environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling techniques, researchers detected genetic material from the bay barnacle Amphibalanus improvisus in Canadian Arctic waters.

This small marine creature, common in Europe and temperate regions worldwide, represents the first confirmed invasive marine species in Arctic Canada. While finding DNA doesn’t necessarily mean thriving populations exist yet, it raises serious red flags about the Arctic’s changing accessibility.

The bay barnacle isn’t just any invader – it’s known for aggressively fouling ships, coastal structures, and even water intake pipes. If established, it could compete with native species for limited resources and potentially disrupt the foundation of Arctic marine food webs that have evolved in isolation for millennia.

A Warming Arctic, a Vulnerable Frontier

Nature’s icy shield is melting away. For thousands of years, extreme cold temperatures acted as an impenetrable barrier protecting Arctic ecosystems from southern species. That protection is rapidly disappearing.

The Arctic’s warming rate outpaces the rest of the planet by at least four times. This dramatic change reduces sea ice coverage, raises water temperatures, and opens shipping routes that were previously impassable. The once-isolated Arctic now faces increased vessel traffic, bringing potential hitchhikers attached to hulls or hidden in ballast water.

These environmental changes create perfect conditions for non-native species to survive where they previously couldn’t. Indigenous communities, whose cultural practices and food security depend on traditional marine resources, may face disruptions to their way of life if invasive species alter the delicate balance of Arctic ecosystems.

Ecological Domino Effect: What’s at Stake

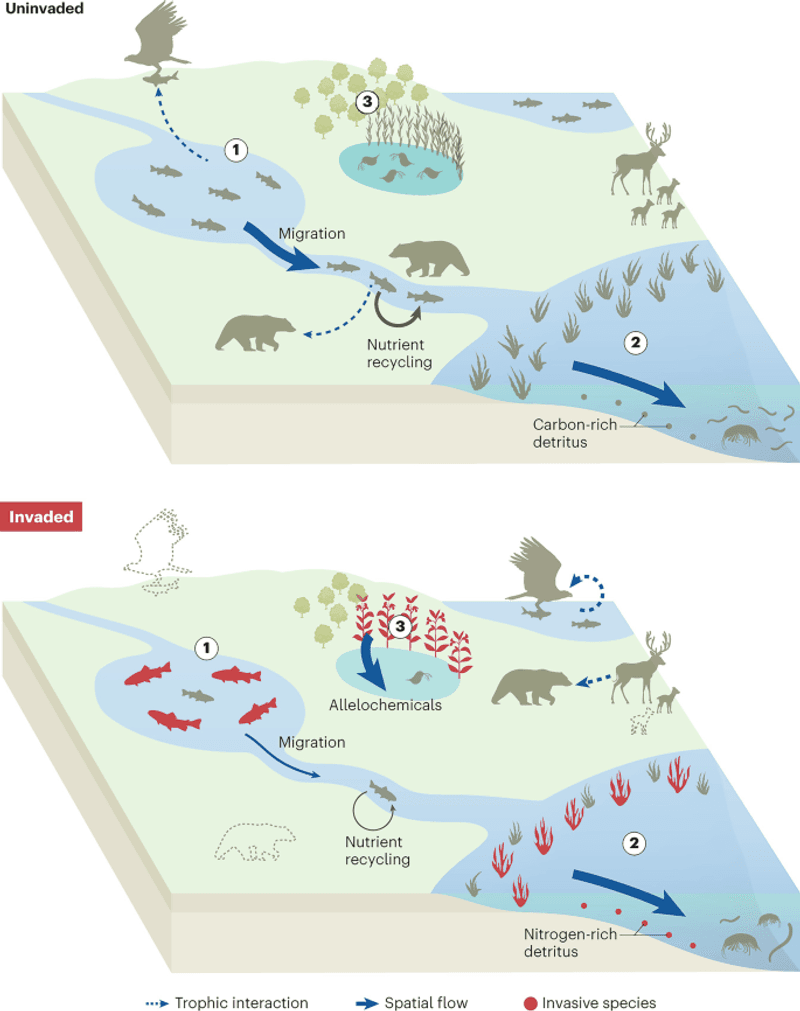

The fragile Arctic food web hangs in delicate balance. Unlike more diverse ecosystems, Arctic marine environments operate with fewer species and more specialized relationships, making them particularly vulnerable to disruption.

When invasive species like the bay barnacle enter these systems, they can trigger cascading effects. Native organisms may suddenly face new competition for food, space, or other resources. The barnacle could potentially introduce unfamiliar diseases or parasites against which Arctic species have no natural defenses.

For Indigenous communities, these ecological shifts translate to real-world consequences. Many northern peoples rely on predictable marine harvests that have sustained their cultures for generations. Changes to species composition could threaten food security and undermine traditional knowledge systems that depend on ecological stability. The barnacle’s arrival might seem small, but in the Arctic’s sensitive environment, even minor changes can ripple throughout the entire ecosystem.

Pathways of Invasion: Human Activity Opens Doors

Ships silently transport stowaways across oceans. As vessels discharge ballast water taken up in distant ports, they release thousands of microscopic organisms into new environments. This pathway likely brought the bay barnacle to Arctic waters.

Arctic shipping has surged dramatically – increasing over 250% since 1990 as sea ice retreats and new routes become navigable. Each vessel represents a potential vector for non-native species, whether through ballast water or organisms attached directly to hulls.

Climate change compounds the problem by making Arctic waters more hospitable to temperate species. Organisms that once would have perished in frigid conditions now encounter temperatures within their survival range. The combination creates a perfect storm: more traffic bringing more organisms into increasingly suitable habitat. Without immediate action to address these pathways, the bay barnacle may be just the first of many unwanted arrivals to Arctic Canada’s changing shores.

Racing Against Time: Prevention and Response

Early detection offers a sliver of hope. The discovery of bay barnacle DNA through advanced eDNA techniques demonstrates that scientists now have tools to identify potential invasions before they become unstoppable – if we act quickly enough.

Prevention remains the most effective strategy. Strengthening international regulations on ballast water treatment and hull cleaning could significantly reduce invasion risks. The Arctic Council has already adopted the Arctic Invasive Alien Species Strategy and Action Plan, but implementation requires greater urgency and resources.

Local knowledge proves invaluable in this fight. Indigenous communities, with their intimate understanding of local ecosystems, can serve as early warning systems for ecological changes. By combining traditional knowledge with scientific monitoring and rapid response protocols, Arctic Canada might still protect its waters from wholesale transformation. The question isn’t whether it’s too late – it’s whether we’ll mobilize quickly enough to make a difference.