Deep in the heart of Germany, archaeologists stumbled upon something extraordinary: ancient footprints frozen in time for 300,000 years. These aren’t just marks in stone—they tell the story of a prehistoric family who once walked along a lakeshore, surrounded by giant elephants and rhinos. This remarkable discovery offers us a rare peek into the lives of our long-lost relatives and the wild world they navigated daily.

Germany’s Oldest Human Tracks

Scientists working in Lower Saxony unearthed fossilized human footprints that date back roughly 300,000 years, making them the oldest ever found in Germany. Unlike scattered bones or stone tools, these impressions capture something far more intimate—a single moment when real people pressed their feet into soft mud.

The tracks belong to Homo heidelbergensis, an extinct human species that came before both Neanderthals and modern humans. What makes this find so special is its ability to freeze a fleeting instant in time. While artifacts show us what ancient people made, footprints reveal where they went and how they moved through their world, offering clues about their daily routines and social bonds.

A Family Walking Together

At the Schöningen site, researchers identified three distinct human footprints with different sizes. Two appear to have been made by younger individuals—possibly children or adolescents—while the third came from an adult. This size variation paints a heartwarming picture of a family group traveling together along the ancient lakeshore.

Rather than a hunting expedition or solo journey, the evidence points to a family outing. Parents and their young ones moving side by side reminds us that family bonds existed long before recorded history. The presence of children’s tracks especially humanizes this deep-time snapshot, showing that prehistoric life wasn’t all about survival—there were moments of togetherness, exploration, and perhaps even play.

Walking Among Giants

The human tracks weren’t alone in the mud. Sharing the same ground were massive footprints from now-extinct megafauna that roamed Europe during the Middle Pleistocene. Scientists identified prints from the straight-tusked elephant, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, a beast that towered over modern elephants.

Even more exciting, researchers found rhinoceros tracks—the first such evidence ever discovered in Europe. These belonged to Stephanorhinus species, massive horned creatures that grazed the ancient landscape. The overlapping prints reveal a bustling ecosystem where early humans navigated alongside enormous animals, sometimes dangerous, sometimes indifferent. This shared muddy surface captures the dynamic relationship between our ancestors and the megafauna that dominated their world, showing coexistence in a time when humans were far from the top of the food chain.

Life by the Ancient Lakeshore

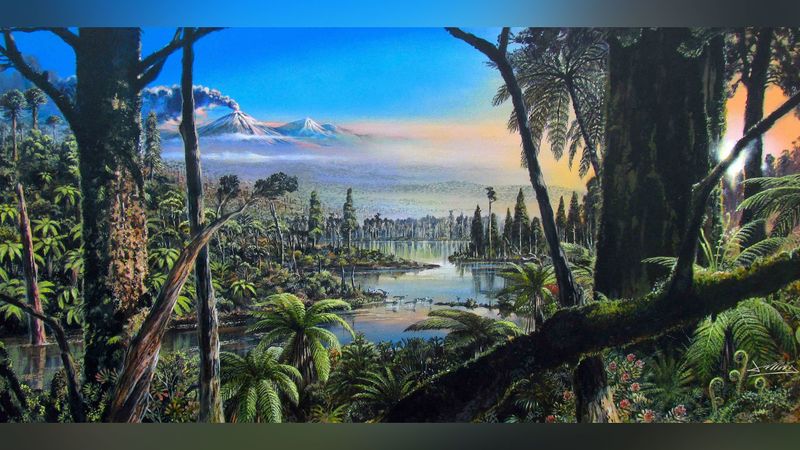

When those footprints were made, the Schöningen area looked vastly different from today. Forests of birch and pine surrounded a sprawling lake, creating a rich habitat teeming with resources. The lakeside environment provided early humans with water, fish, and places to hunt or gather.

Seasonal changes brought different foods: fruits ripened in summer, mushrooms sprouted in autumn, and fresh shoots appeared in spring. Leaves and plant materials offered nutrition and possibly materials for shelters or tools. But the lake’s edge wasn’t without danger—water levels shifted unpredictably, and predators lurked in the forests. Still, this landscape gave Homo heidelbergensis the variety they needed to survive and thrive, balancing opportunity with risk in their daily travels.

More Than Just Survival

Footprints reveal something bones and tools cannot: behavior in motion. These tracks don’t just show that people existed—they capture how they moved, where they wandered, and possibly what they were doing. The spacing and depth of the prints suggest leisurely walking rather than frantic running, hinting at exploration or casual travel.

The children’s prints are particularly telling. Young people weren’t just tagging along on serious survival missions; they were part of everyday life, possibly playing, learning, or simply enjoying the lakeside. This discovery vividly humanizes a scene from 300,000 years ago, reminding us that prehistoric families shared moments of normalcy, curiosity, and connection—qualities that make us recognize them as fundamentally human, despite the vast gulf of time.

Protecting and Understanding the Find

Preserving footprints is far trickier than storing bones or pottery. These delicate impressions exist in fragile sediment layers that can crumble or erode if not carefully protected. Researchers must work quickly and meticulously to document and stabilize the site before weather or time destroys the evidence.

Future research will focus on advanced dating techniques to pinpoint the exact age of the tracks, paleoenvironmental reconstruction to understand seasonal conditions, and comparative analysis with other sites across Europe and Africa. Scientists hope to map additional tracks at Schöningen, expanding the footprint census and building a fuller picture of how Homo heidelbergensis families moved through their environment. Each new discovery adds another brushstroke to the portrait of our ancient relatives.