Scientists have made a shocking discovery that might change how you think about bottled water. Recent research from Columbia and Rutgers Universities found that most bottled water contains hundreds of thousands of tiny plastic particles in every liter. Even more surprising, only one brand out of three tested came back completely clean, with no detectable microplastics or nanoplastics at all.

Discovering Nanoplastics in Bottled Water

Researchers at two major universities published groundbreaking findings that reveal bottled water contains far more plastic than anyone previously thought. The study, which appeared in a prestigious science journal, found an average of 240,000 plastic fragments per liter. That number is much higher than earlier research suggested.

Most of these particles are nanoplastics, which are incredibly tiny—smaller than 1 micrometer. About 90 percent fall into this category, while the rest are slightly larger microplastics. Because nanoplastics are so minuscule, scientists worry they might easily cross into our bloodstream or build up in organs.

This raises important questions about long-term health effects. The sheer volume of particles found was startling to even the researchers themselves, prompting calls for more investigation into what we’re really drinking.

How the Study Was Conducted and What It Measured

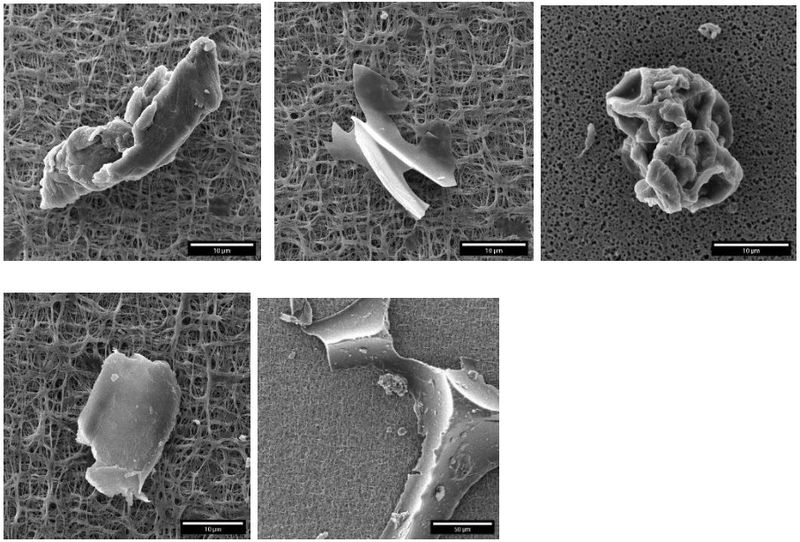

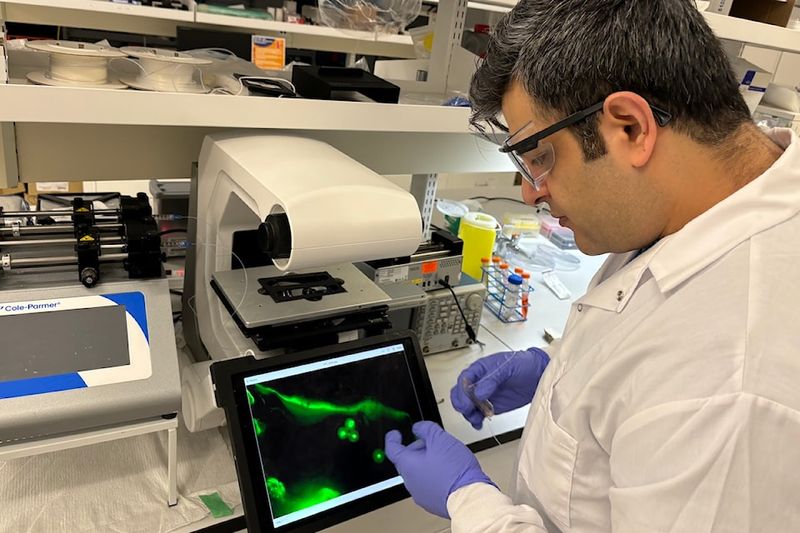

To spot these microscopic invaders, the research team used a cutting-edge technique called stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. They paired it with artificial intelligence algorithms trained to identify seven different types of plastic polymers. This combination allowed them to detect particles as small as 100 nanometers—far tinier than what older methods could find.

Three different bottled water brands sold across the United States were tested. The brands remain unnamed because of ethical and legal reasons. Results varied quite a bit, showing between 110,000 and 370,000 particles per liter depending on which brand was examined.

Among the plastics identified were PET (the material bottles are made from) and polyamide, also known as nylon. This sophisticated approach marks a major leap forward in understanding plastic contamination.

Sources of Contamination and The One Clean Brand

Where do all these plastic particles come from? Scientists believe contamination happens at multiple stages. The bottle material itself can shed PET fragments, but that’s not the only source. Water treatment, filtration systems, and the bottling process all contribute plastic particles.

Friction between bottle caps and containers, leaching from packaging materials, or abrasion inside purification equipment could all introduce unwanted particles. It’s a complex problem without a single simple fix. However, there’s a glimmer of hope in the data.

One of the three brands tested showed absolutely no detectable microplastics or nanoplastics. The company’s name hasn’t been released publicly, but its success proves that producing ultra-clean bottled water is possible. With careful manufacturing controls and quality checks, contamination can apparently be avoided entirely.

Implications, Uncertainties and What Comes Next

Despite these dramatic findings, many mysteries remain unsolved. The study authors warn that detection limits, potential contamination during sample collection, and possible errors in computer classification might affect accuracy. Only about 10 percent of the particles found could be matched to known plastic types—the majority remain chemically unidentified.

Here’s the really important part: nobody knows yet whether ingesting nanoplastics actually harms human health. Researchers stress that toxicological studies are desperately needed to understand if these particles pose genuine risks. Just because something is present doesn’t automatically mean it’s dangerous.

The research team plans to expand their work significantly. Future studies will examine tap water, various foods, snow, and even human tissues. This broader investigation should help map exactly how widespread these particles are in our environment and bodies.