Ancient engineers accomplished something extraordinary more than five millennia ago: they moved a massive 2-tonne stone slab across the landscape of southern Spain. The Matarrubilla stone, found in a ceremonial tomb near Seville, has puzzled researchers for years because it clearly didn’t come from nearby. Now, archaeologists believe they’ve solved the mystery—and the answer involves boats, skilled sailors, and a level of prehistoric sophistication that rewrites what we thought we knew about life during the Copper Age.

The Matarrubilla Stone’s Mysterious Origins

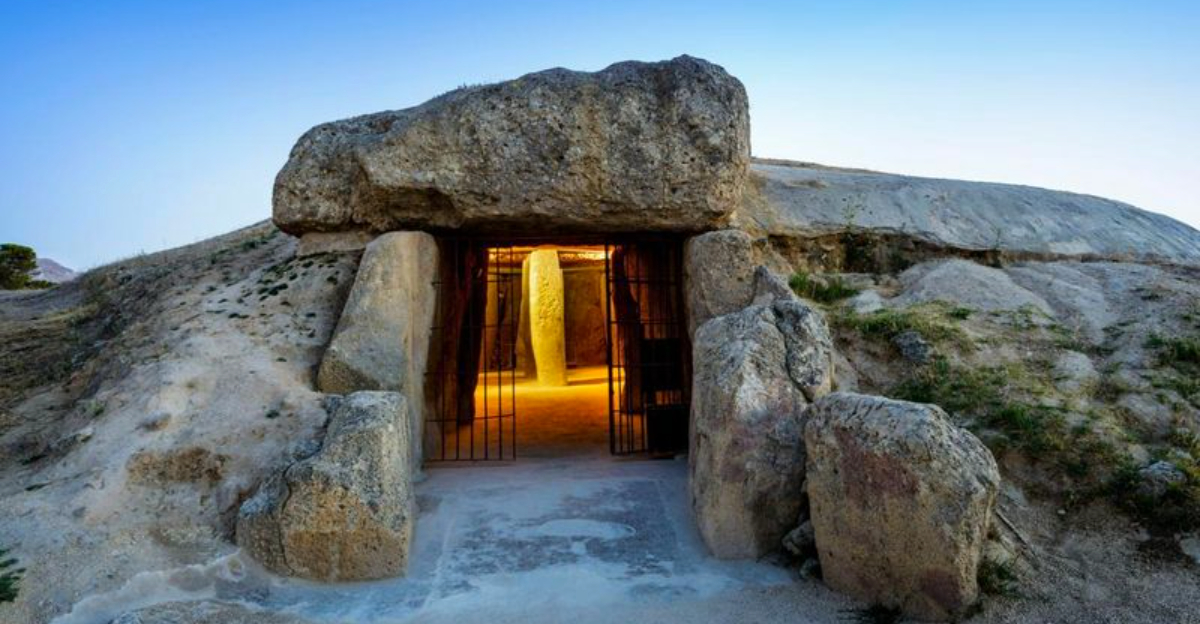

Deep within a circular tomb chamber at the Valencina archaeological site lies a remarkable gypsum slab that has captivated scientists. Measuring 1.7 meters long and 1.2 meters wide, this hefty stone weighs around 2 tonnes—about as much as a small car. Its placement inside the tholos tomb wasn’t random; the precision suggests people saw it as spiritually significant during the Copper Age.

What really stumped experts was figuring out where this stone came from. The local geology around Seville doesn’t match the stone’s composition, meaning ancient communities had to bring it from somewhere else. That realization sparked a bigger question: how did people without wheels, cranes, or modern machinery haul such a beast across difficult terrain? The stone’s very presence hints at determination, planning, and capabilities far beyond what many assumed about prehistoric societies in Iberia.

Boats as Ancient Heavy-Lifting Champions

Forget dragging stones over hills and valleys—researchers now believe prehistoric people took to the water instead. Maritime transport would have been a game-changer, allowing communities to float the 2-tonne slab along coastal routes and river systems rather than wrestling it across rugged land. Picture sturdy wooden boats, carefully designed to handle heavy cargo, gliding along ancient waterways 5,300 years ago.

This theory flips our understanding of early seafaring on its head. Building a vessel strong enough to carry such weight required knowledge of boat construction, balance, and buoyancy. Navigators also needed to understand tides, currents, and weather patterns to ensure safe passage. The whole operation demanded teamwork, from loading the stone without capsizing to steering through tricky waters, proving that Copper Age sailors were far more skilled than history books often suggest.

Coordinated Effort Behind the Journey

Hauling a 2-tonne stone wasn’t a solo project—it took a village, literally. Communities needed strong ropes, clever rigging systems, and plenty of muscle power just to get the slab onto a boat. Once aboard, keeping it stable during transport required constant attention and adjustments, especially if waves picked up or the current shifted unexpectedly.

Beyond the technical challenges, this operation reveals impressive social organization. Leaders had to rally workers, assign tasks, and keep everyone fed and motivated throughout what might have been a multi-day journey. The fact that they went to all this trouble for a stone destined for a tomb tells us something profound: this wasn’t just about moving rock. The stone carried deep symbolic meaning, perhaps representing ancestral connections or divine power, making the enormous effort worthwhile in the eyes of Copper Age society.

Rewriting Prehistoric Maritime History

If ancient Iberians really did ship megaliths by sea, then we’ve been underestimating their capabilities all along. This discovery suggests that maritime networks during the Copper Age were robust enough to support not just fishing or local travel, but ambitious long-distance transport projects. Coastal communities might have been connected through trade routes, ritual exchanges, or shared cultural practices that spanned impressive distances.

Archaeologists are now taking a fresh look at other mysterious megalith sites across Europe. When researchers find massive stones far from their geological source, the default assumption has usually been overland dragging. But maybe we should be asking about rivers and coastlines instead. Did other ancient cultures use similar maritime strategies? This single stone near Seville opens a window into a prehistoric world where boats weren’t just for catching fish—they were essential tools for moving the sacred and the significant.