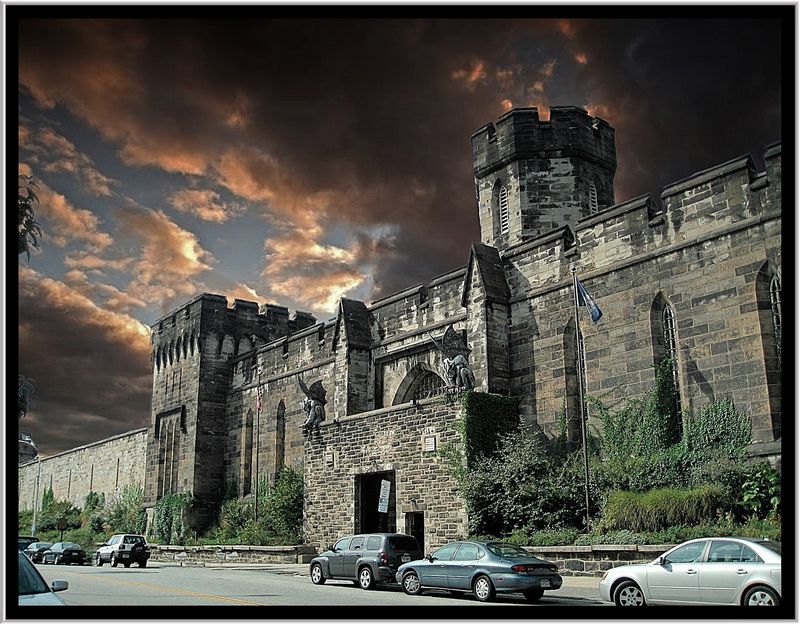

Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary stands as one of America’s most fascinating architectural landmarks—a crumbling fortress where history, design, and justice collide. Built in 1829, this Gothic-style prison was once the model for hundreds of correctional facilities worldwide, designed to reform criminals through isolation and reflection. Today, its empty hallways and decaying cell blocks tell stories of innovation, controversy, and the ghosts that some believe still roam its corridors.

A Vision of Reform in Gothic Stone

Back in the early 19th century, reformers in Pennsylvania sought a new kind of prison—one that would not only punish but actually steer offenders toward reflection and change. The Eastern State Penitentiary opened in 1829 in Philadelphia, designed by architect John Haviland in a revolutionary “separate system” layout.

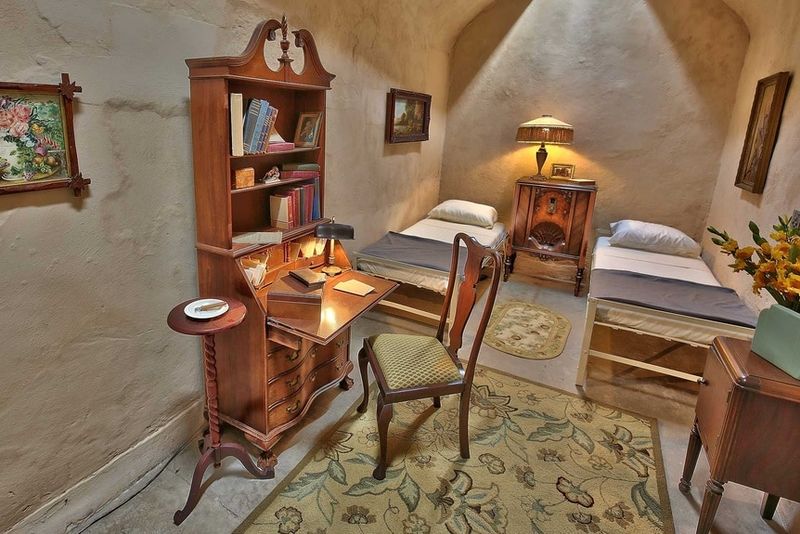

The building’s architecture featured a central rotunda with cell-blocks radiating outward—allowing one guard to oversee multiple wings from a single vantage point. Each cell boasted a skylight known as the “Eye of God,” symbolizing divine watchfulness over the individual prisoner.

The combination of Gothic facades and solitary cells created an imposing space where isolation was meant to inspire penitence rather than just fear. This bold experiment in design reflected the era’s idealistic belief that architecture itself could transform human behavior.

Notorious Inmates & Architectural Legacy

Over its decades of operation from 1829 to 1971, Eastern State Penitentiary held some of America’s most infamous criminals—including Al Capone and Willie Sutton—and it served as the blueprint for more than 300 prisons around the world. The institution’s radical design and idealistic ethos made it a model of its time, but its legacy is complicated.

Solitary confinement, large-scale isolation and psychological stress eventually garnered serious criticism from reformers and medical professionals alike. What began as a humane alternative to physical punishment became recognized as its own form of cruelty.

Its corridors, once bustling with guards and inmates, now echo with emptiness—a haunting reminder of both ambition and addiction to control. The prison’s influence shaped correctional thinking for generations, leaving an architectural and philosophical footprint that still sparks debate today.

From Prison to Ruin to Museum

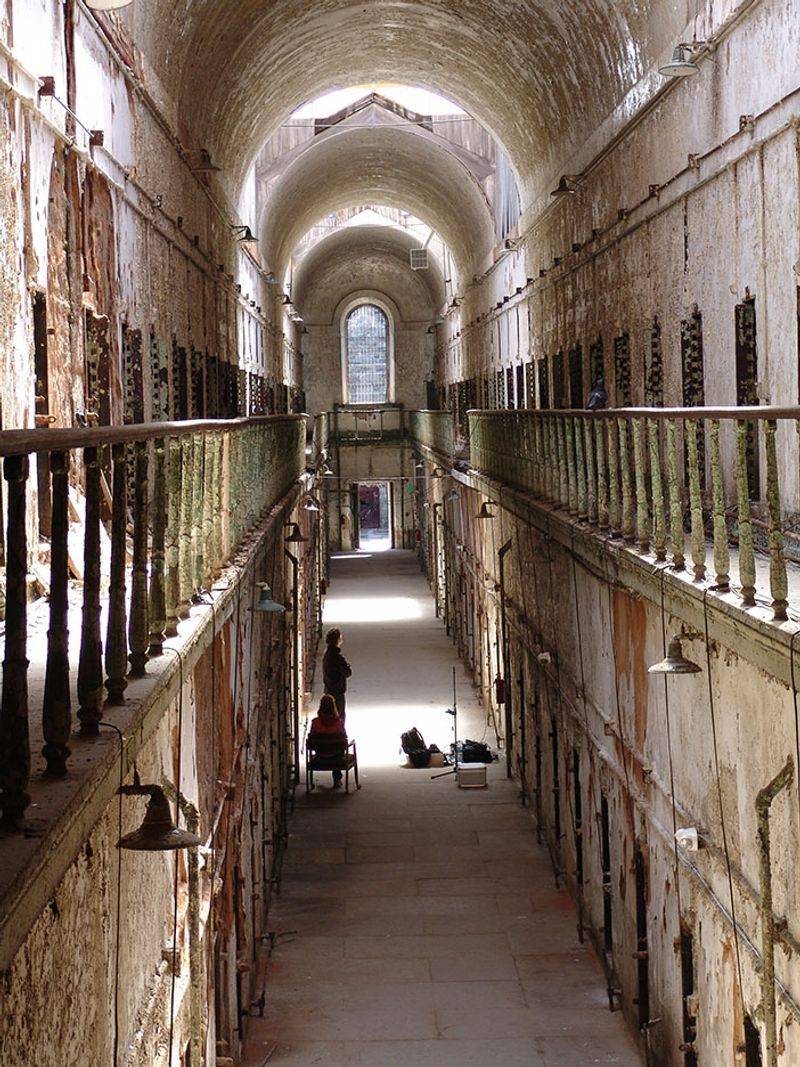

After closing in 1971, the massive complex fell into disuse and decay. But in 1994, the site reopened as a museum and historic landmark, transitioning from carceral space to cultural destination.

Visitors now wander through cell blocks frozen in time, graffiti-marked walls and original fixtures still intact. Audio tours narrated by actor Steve Buscemi guide guests through history, art installations and exhibits that raise questions about incarceration, justice and memory.

The preserved ruin of Eastern State invites reflection—not only on what the building once was, but on what prisons in America have become. Modern art installations blend with crumbling walls, creating a unique dialogue between past and present. This transformation allows thousands of visitors each year to confront uncomfortable truths about punishment, rehabilitation, and the human cost of our criminal justice system.

Atmosphere, Haunting & Reflection

Walking through Eastern State, one senses how architecture and power interweave. Narrow corridors, vaulted ceilings, solitary-cell skylights and the radial layout combine to create a palpable tension that visitors feel immediately upon entering.

The site is frequently cited as one of America’s most haunted locations—shadows, footsteps and whispers seem to linger long after prisoners left. Ghost hunters and paranormal enthusiasts flock here, drawn by tales of spectral encounters and unexplained phenomena.

Yet beneath the ghost stories lies a deeper layer: this place stands at the crossroads of prison-reform history, architectural innovation and social justice. For visitors, it is more than a haunted tour—it is an encounter with the enduring questions of confinement, freedom and human dignity. The building’s haunting quality comes not just from ghost stories, but from confronting the real human suffering that occurred within its walls.