The Great Depression was one of the hardest times in American history, lasting from 1929 to the early 1940s. Millions of people lost their jobs, homes, and savings almost overnight. The phrases and sayings that came out of this era tell the real story of survival, resourcefulness, and the incredible strength of everyday people who had to make do with almost nothing.

Use It Up, Wear It Out, Make It Do, or Do Without

This mantra became the heartbeat of every household during the Depression years. Nothing could be thrown away carelessly because replacing even the smallest item simply wasn’t possible for most families. People darned socks until they were more patch than original fabric, turned old flour sacks into dresses, and found creative ways to stretch every resource.

Mothers taught their children that wastefulness was almost sinful in those lean times. A broken tool would be fixed with wire and ingenuity rather than replaced. Leftover food scraps went into the next meal or fed to animals, ensuring nothing edible ever hit the trash.

This saying captured not just frugality but a whole mindset of resilience and creativity that helped families survive.

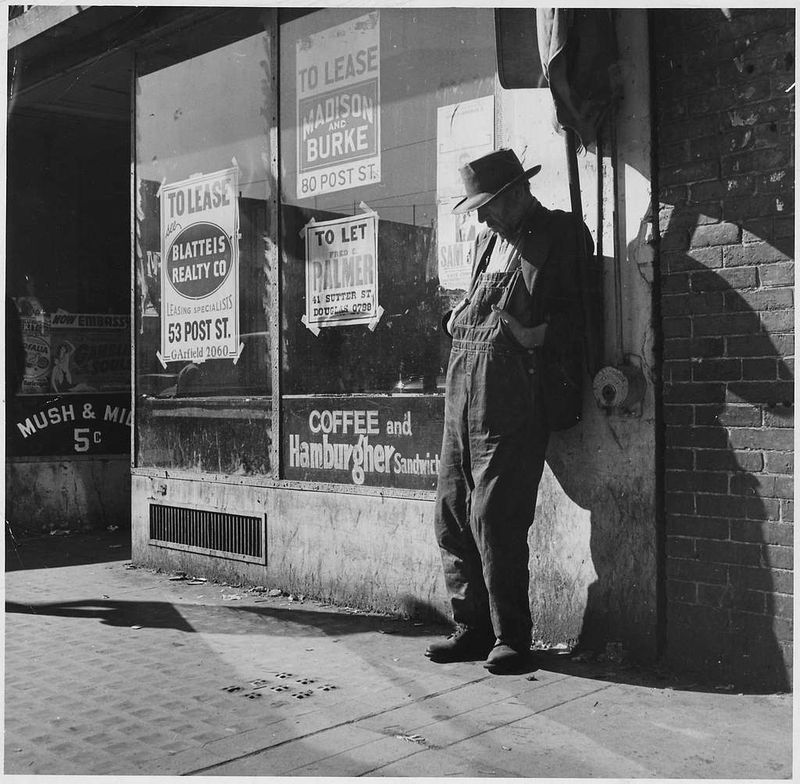

Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?

Born from a 1932 song, this phrase became the anthem of joblessness and desperation. Men who had once worked proudly in factories, on construction sites, or in offices found themselves on street corners asking strangers for the smallest coin. The dime represented not just money but dignity slipping away.

The song’s lyrics struck a nerve because they told the story of veterans and workers who had built the country but were now abandoned. These weren’t lazy people—they were skilled workers whose jobs had simply vanished when the economy collapsed. Standing on corners with outstretched hands was humiliating, yet necessary for survival.

This saying reminds us how quickly fortune can change for anyone.

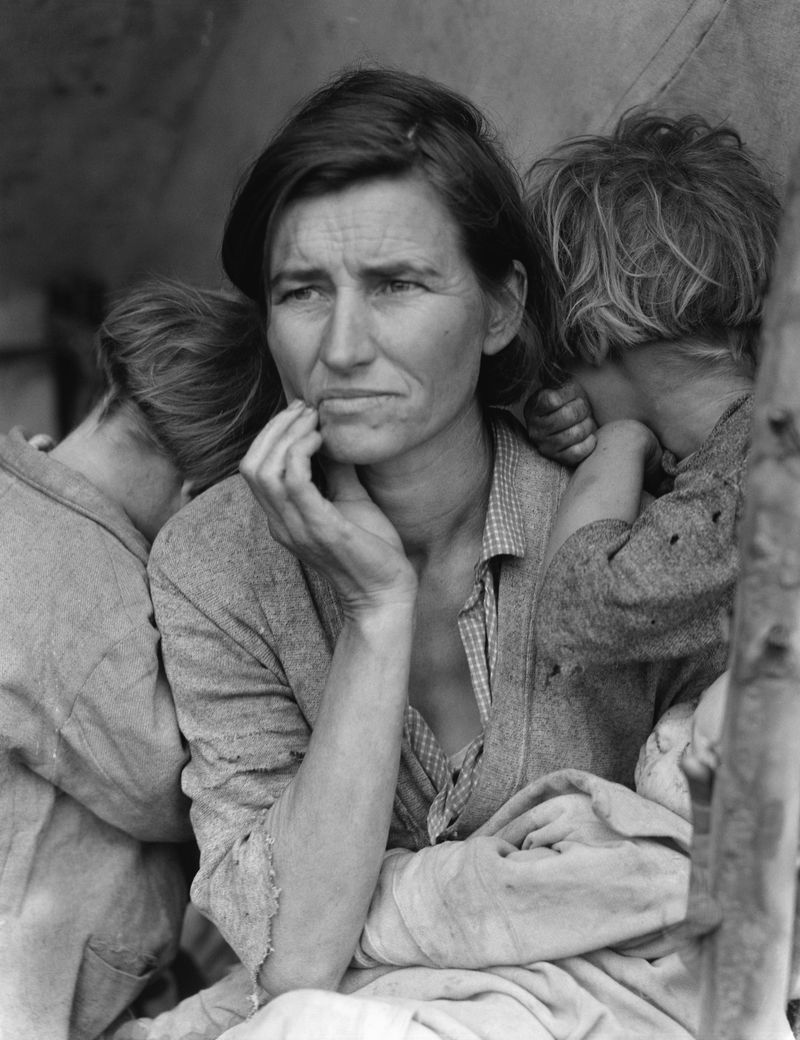

We’re in the Soup

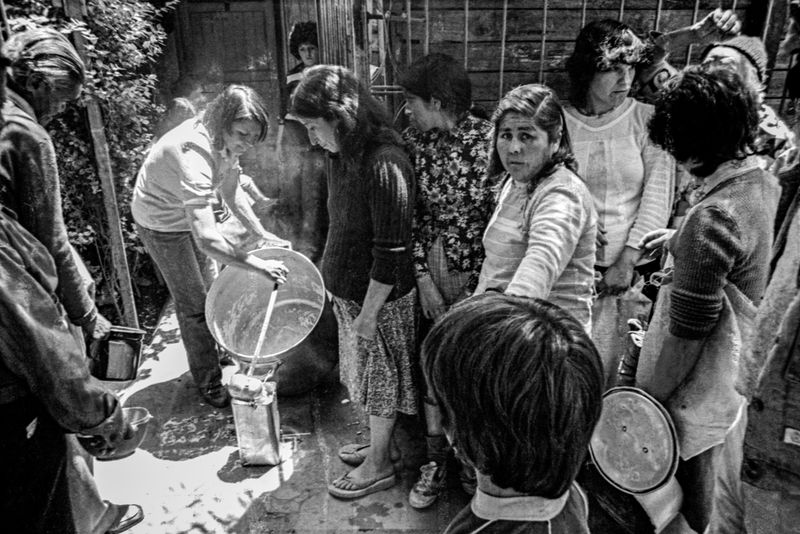

When someone said they were in the soup, they meant trouble had arrived—usually financial trouble with no easy way out. The phrase took on extra meaning during the Depression because soup kitchens became lifelines for millions of hungry Americans. Actual soup, thin and watery as it often was, represented both charity and rock bottom.

Breadlines and soup kitchens stretched around city blocks as unemployed workers and their families waited hours for a simple meal. Standing in those lines meant admitting you couldn’t feed yourself or your family anymore. The shame was real, but hunger was more powerful.

This slang captured the grim reality that for many people, survival meant literally being in the soup.

Too Poor to Paint, Too Proud to Whitewash

Pride remained even when money disappeared completely. This saying described families who couldn’t afford proper paint for their homes but refused to use cheap whitewash as a substitute. It spoke to maintaining dignity even when circumstances had stripped away almost everything else.

Whitewash was the poor person’s solution—cheap, temporary, and obvious to everyone who saw it. Some folks felt that using it announced their poverty to the whole neighborhood. They’d rather let their houses weather naturally than fake prosperity with a thin coating that fooled no one.

The phrase shows how people held onto self-respect when material possessions were gone. Dignity didn’t cost money, and sometimes that was all families had left to claim as their own.

Patch It, Don’t Pitch It

Throwing anything away was practically unthinkable during the Depression. Clothes were patched until they became patchwork quilts of repairs, shoes were resoled multiple times, and broken tools were fixed with whatever materials were handy. The trash bin was the last resort, not the first.

Children wore hand-me-downs from older siblings, and those clothes had often been patched by previous wearers too. Mothers became expert seamstresses out of necessity, turning worn shirts into usable rags and old dresses into quilts. Men learned basic cobbling to keep their work boots functional another season.

This practical philosophy saved families money they didn’t have. More importantly, it taught self-reliance and problem-solving skills that lasted generations beyond the Depression itself.

We Ate What We Could Catch, Grow, or Beg For

Grocery shopping became a luxury most families couldn’t afford regularly. Survival meant eating whatever you could produce, hunt, fish, or occasionally receive from others. Gardens became essential, not decorative, and every family with land grew vegetables to supplement their meager diets.

Men fished in local streams and hunted small game when possible. Children foraged for wild berries, nuts, and edible plants. Some families swallowed their pride and asked neighbors or relatives for help when starvation became a real threat. There was no shame in begging when your children were hungry.

This raw, honest phrase captures the desperation of feeding a family when traditional income had vanished and stores were out of reach financially.

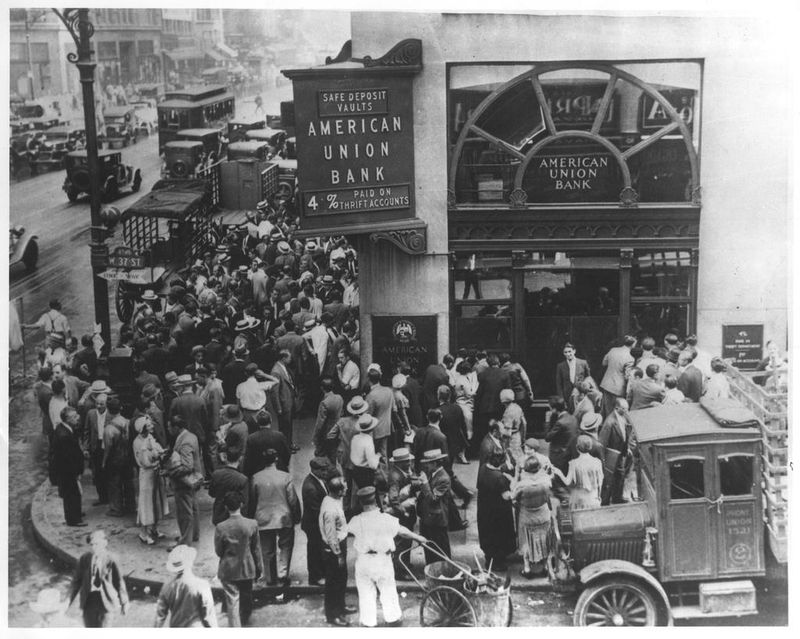

When the Banks Closed, So Did Our Future

Bank failures devastated communities almost overnight. Families who had saved for years watched their life savings disappear when banks shut their doors permanently. There was no insurance protecting deposits, so when a bank failed, that money was simply gone forever.

People had trusted these institutions with their futures—money for retirement, for their children’s education, for emergencies. The closures didn’t just mean lost money; they meant lost dreams and security. Farmers couldn’t get loans for seeds. Businesses couldn’t make payroll. Families couldn’t access funds for basic necessities.

This saying reflects the deep connection between financial institutions and personal hope. When the banks collapsed, they took people’s faith in the system and their vision of tomorrow with them.

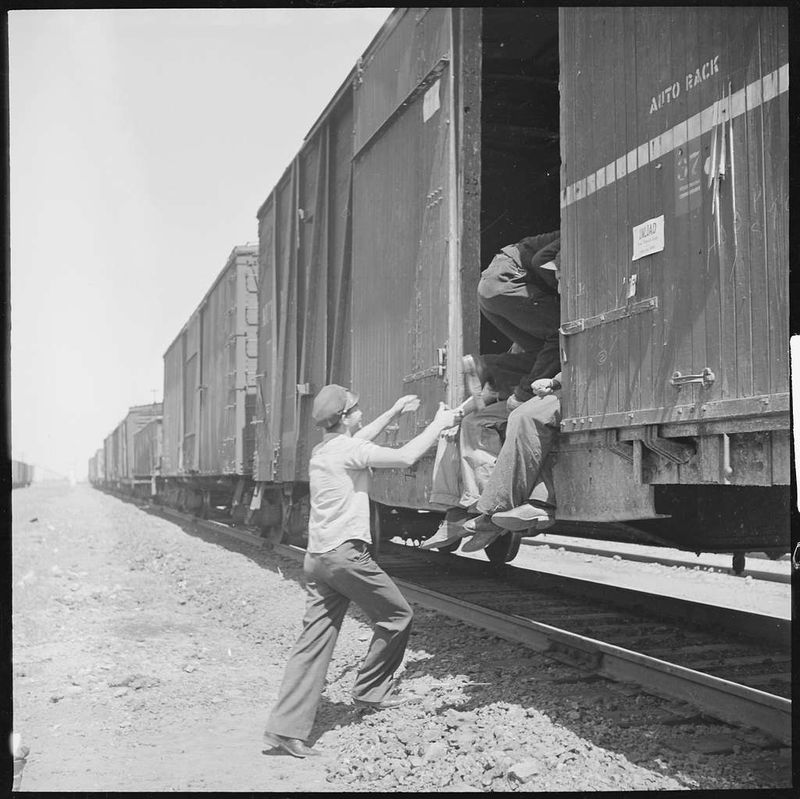

Rode the Rails

Thousands of unemployed men became transients, hopping freight trains illegally to search for work across the country. These weren’t criminals or wanderers by choice—they were desperate workers following any rumor of employment. Riding the rails meant danger, discomfort, and uncertainty, but staying home meant starvation.

Railroad bulls (security guards) tried to keep hobos off the trains, sometimes violently. Men risked arrest, injury, or death jumping onto moving cars. They traveled in groups for safety, sharing information about which towns might have work and which were hostile to drifters.

This phrase represents the mobility of desperation. Home offered nothing, so men kept moving, hoping the next town would be different, always searching for that elusive job.

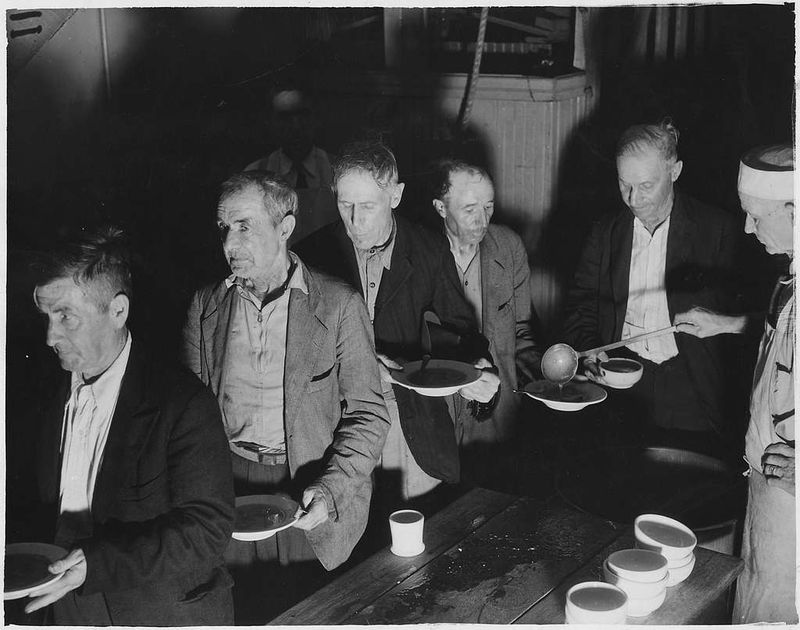

Three Hots and a Flop

This grim phrase described the bare minimum for survival: three hot meals and a place to sleep. Relief camps and shelters offered this basic package to homeless men who had nowhere else to go. It wasn’t comfort or security, just the essentials to keep body and soul together another day.

A flop meant a bunk or cot in a crowded room with dozens of other desperate men. The hot meals were usually simple soup, bread, and coffee—nothing fancy but enough to prevent starvation. Men lined up for hours to get this minimal relief, grateful for even this much help.

The phrase shows how low the baseline for survival had dropped. Just having food and shelter—things most had taken for granted—became the goal.

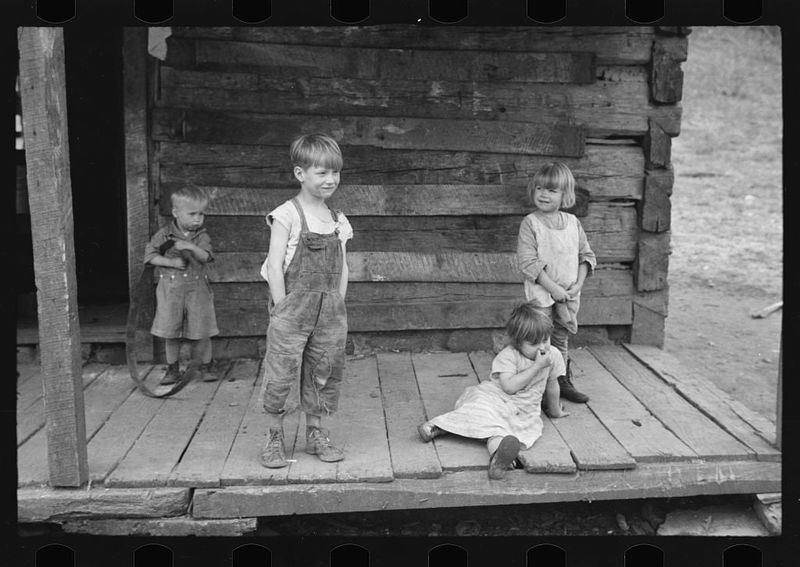

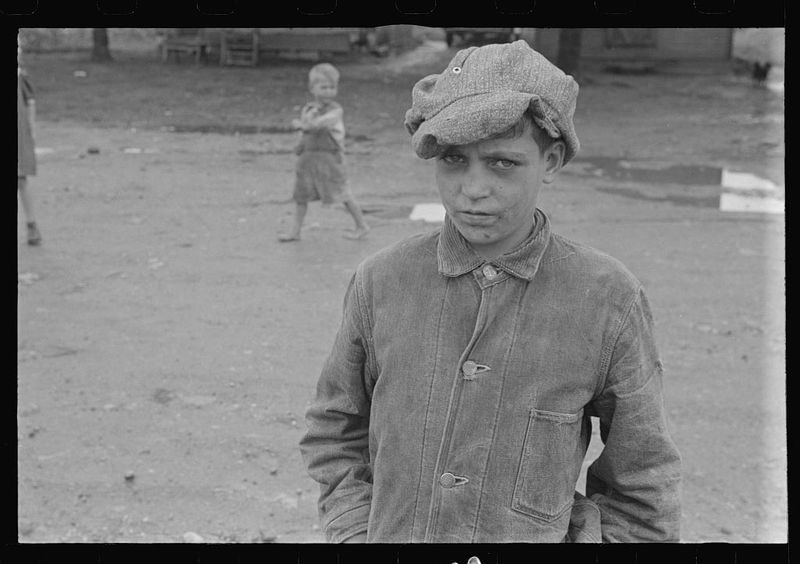

We Were So Poor, We Didn’t Know We Were Poor

When everyone around you struggles equally, poverty becomes normal. Children especially might not realize their situation was desperate because their neighbors, classmates, and friends all lived the same way. There was no comparison to make them feel deprived.

This bittersweet saying captures both innocence and community solidarity. Families shared what little they had, and communities pulled together. Kids played with homemade toys and found joy despite material lack. Adults made do without complaint because complaining changed nothing.

Yet the phrase also holds sadness—poverty was so widespread and deep that it became invisible to those living in it. The hardship was no less real for being universal and unrecognized by those experiencing it daily.

Don’t Throw That Out—You Might Need It Someday

Uncertainty about the future made people save everything that might possibly have future use. String was wound into balls, jars were washed and stored, buttons were cut from worn-out clothes, and scraps of fabric were saved. Nothing with potential value was discarded.

This wasn’t hoarding in the modern sense—it was practical survival strategy. When you couldn’t afford to buy something new, having materials on hand for repairs or projects was essential. That saved jar might store preserves next summer. That piece of wire might fix a broken tool next month.

The habit of saving everything stuck with Depression survivors for life. Even decades later, many couldn’t bring themselves to throw away anything potentially useful, shaped forever by years when waste meant hunger.

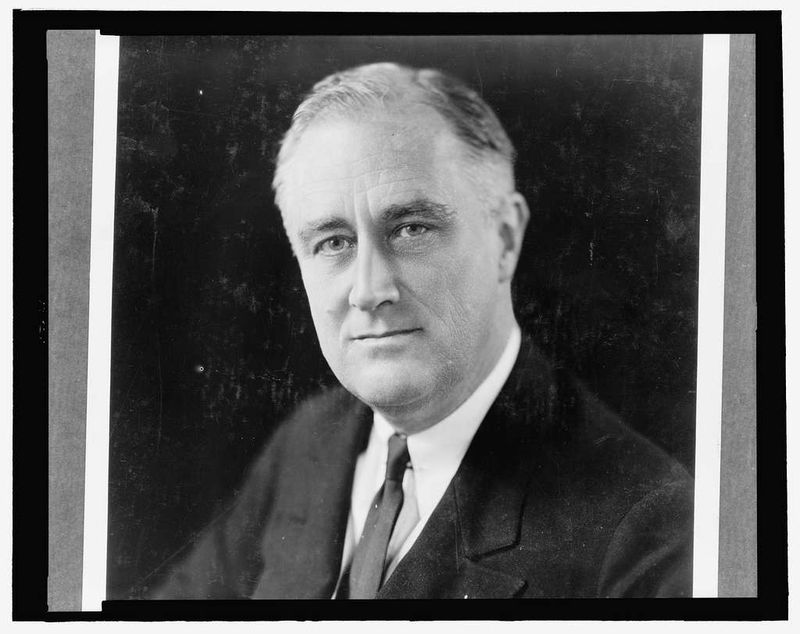

The Only Thing We Have to Fear Is Fear Itself

Franklin Roosevelt spoke these famous words during his 1933 inaugural address, targeting the psychological crisis gripping America. Beyond unemployment and poverty, fear itself was paralyzing the nation. People were too scared to spend, invest, or hope, which made the economic situation even worse.

Banks failed partly because panicked depositors rushed to withdraw money, creating runs that collapsed institutions. Businesses couldn’t recover because consumers stopped buying anything but absolute necessities. Fear fed on itself, creating a vicious cycle that deepened the Depression.

Roosevelt understood that restoring confidence was as important as economic policy. His words acknowledged the real danger of letting terror control decisions. While fear was justified by circumstances, letting it dominate meant surrender to despair and paralysis.

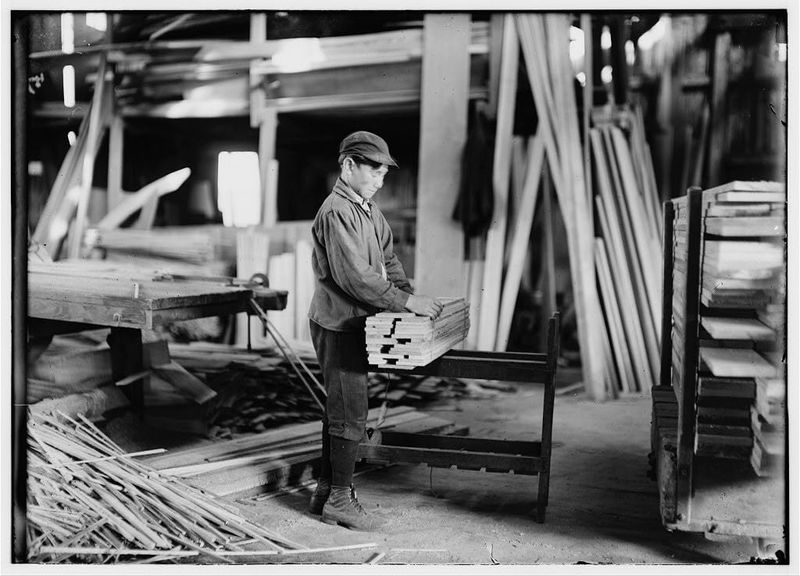

Fighting for Pennies

Jobs became so scarce that dozens of men would compete for a single position paying almost nothing. Employers could offer pennies per hour because desperate workers would accept anything. The phrase captures both the low wages and the fierce competition for even terrible jobs.

Men would gather at factory gates or docks early each morning, hoping to be chosen for a day’s work. Sometimes they’d work for food instead of money. The competition was humiliating—grown men begging for work that barely paid enough to feed their families.

Employers took advantage, knowing workers had no alternatives or bargaining power. Yet people kept fighting for those pennies because even tiny wages were better than nothing when your children were hungry and rent was due.

No Jobs, No Hope

Unemployment peaked at roughly 25 percent in 1933, meaning one in four workers had no job. This stark phrase connected employment directly to hope—without work, people saw no path forward. Jobs provided more than money; they gave purpose, structure, and dignity to daily life.

Losing work meant losing identity for many men who defined themselves by their labor. Months stretched into years without employment for some, crushing spirits and destroying families. The connection between work and hope was painfully clear when both disappeared together.

Communities struggled when so many were jobless simultaneously. Local businesses failed without customers. Tax revenues dropped, cutting public services. The phrase captured a truth everyone understood: employment was the foundation everything else was built on, and that foundation had crumbled.

Living on Hope and Rainwater

Farmers during the Depression faced drought on top of economic collapse. Rainwater collected in barrels became precious for drinking, cooking, and keeping animals alive. The phrase combined literal truth with metaphor—people survived on almost nothing material, sustained by hope alone.

Wells ran dry across the Midwest during the Dustbowl years. Families rationed water carefully, using it multiple times before finally discarding it. A good rain was cause for celebration because it meant life could continue a bit longer. Without rain, crops died and families faced starvation.

Hope kept people going when logic said to give up. They hoped next season would bring rain, next month would bring work, next week would bring relief. Sometimes hope and rainwater were literally all sustaining life.

Making a Meal Out of Nothing

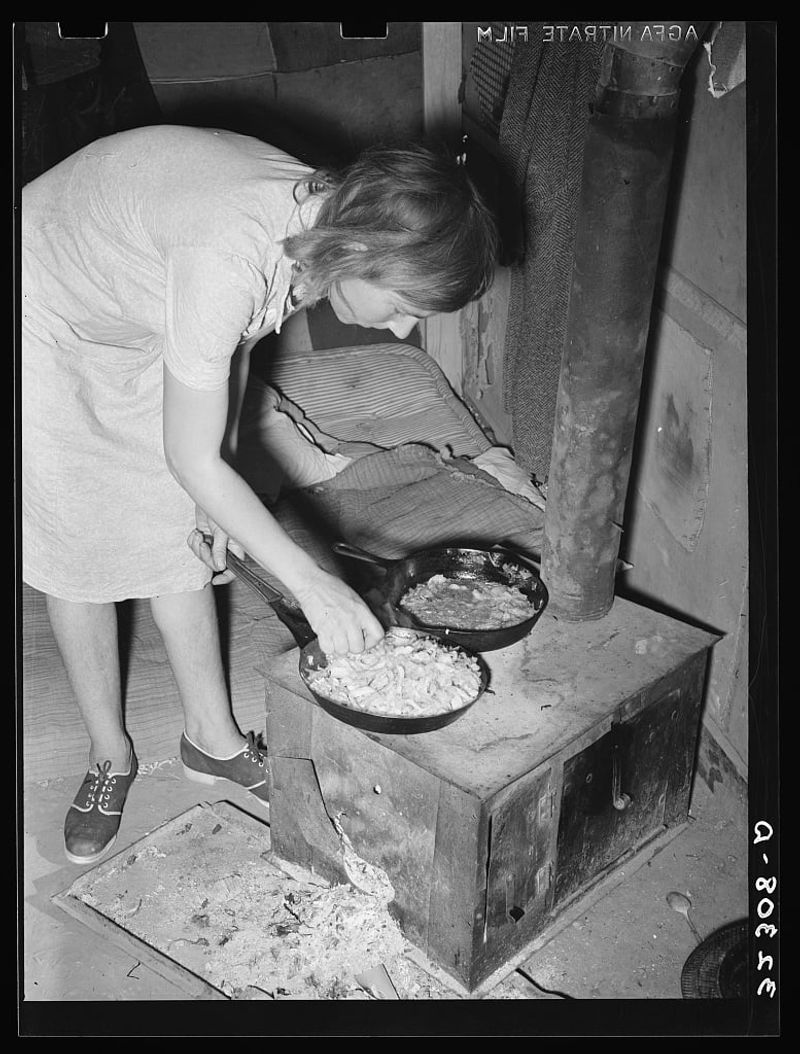

Mothers became magicians, creating meals from ingredients that seemed insufficient to feed anyone. A single potato might become soup for six people. Stale bread turned into pudding. Bones were boiled repeatedly for broth. Creativity in the kitchen meant survival.

Women traded recipes for stretching food further—how to make flour last longer, how to use every vegetable scrap, how to make filling dishes from almost nothing. Meat became a rare luxury, appearing only in tiny amounts to flavor otherwise vegetable-based meals. Water and seasonings bulked up everything.

The phrase honors the incredible resourcefulness of Depression-era cooks who kept families fed against impossible odds. Their skills and determination prevented starvation in countless homes when money for food had run out completely.

Hoovervilles

Homeless families built entire settlements from scrap materials on the edges of cities. These shanty towns were mockingly called Hoovervilles, blaming President Hoover for the economic disaster. Shacks made from cardboard, tin, and wood scraps housed thousands of people who had lost everything.

Hoovervilles appeared in nearly every major city. They had their own informal governments and communities. Residents tried to maintain dignity and order despite living in structures barely worthy of being called shelter. Families did their best to create homes from refuse.

The name itself was political protest. By attaching Hoover’s name to these symbols of poverty and failure, people expressed their anger at leadership they felt had abandoned them during the crisis. These settlements stood as visible reminders of how far prosperity had fallen.

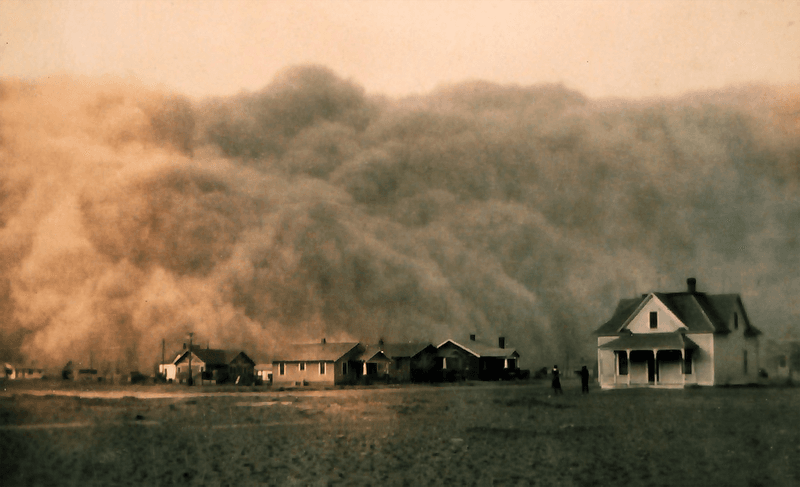

Dust Bowl Days

Environmental disaster compounded economic catastrophe across the Great Plains. Years of drought combined with poor farming practices turned topsoil to dust that blew away in massive storms. Farms became deserts, crops failed completely, and families faced impossible choices about staying or leaving.

Dust storms blocked out the sun, buried homes, and made breathing difficult. People stuffed wet towels under doors to keep dust out, but it penetrated everywhere. Livestock died from breathing dust. Children developed respiratory illnesses. The land itself seemed to be dying.

Thousands of families abandoned their farms and headed west, hoping for better conditions. Those who stayed endured years of hardship, watching their livelihoods literally blow away. The Dust Bowl became synonymous with Depression-era suffering in rural America.

Scrip Instead of Dollars

Some employers paid workers in scrip—company-issued tokens or paper redeemable only at company stores. This trapped workers in a system where their labor never converted to real money they could spend freely. Scrip was worth less than dollars and kept workers dependent on their employers.

Company stores charged inflated prices, knowing workers had no choice but to shop there. Families couldn’t save money or improve their situations because scrip never accumulated value. The system essentially created debt peonage where workers could never get ahead no matter how hard they labored.

Scrip represented powerlessness during the Depression. Workers were grateful for any employment but trapped by payment systems that prevented real economic progress or independence from their employers.

Okies and Migrants

Families fleeing the Dust Bowl were called Okies, even if they came from Kansas, Texas, or other states. The term carried prejudice—these migrants faced discrimination when arriving in California and other western states seeking work. Locals feared they’d take jobs and resources.

Entire families packed everything they owned onto trucks and headed west on Route 66, chasing rumors of agricultural work. The journey was dangerous and expensive. Many ran out of money before reaching their destinations. Those who arrived often found conditions barely better than what they’d left.

Migrant camps sprung up where these families lived in terrible conditions while working as farm laborers. The phrase represents both desperate hope and the harsh reality that moving didn’t solve poverty—it just relocated it.

Relief Lines and Government Cheese

Government relief programs distributed food and supplies to desperate families. Standing in relief lines meant admitting you couldn’t provide for yourself, which was humiliating for proud workers. Yet millions had no choice—it was relief or starvation.

The government distributed surplus commodities like cheese, flour, and canned goods. These programs prevented mass starvation but came with social stigma. Neighbors could see who needed relief, and accepting help felt like failure to many. Children sometimes faced teasing when classmates knew their families received government assistance.

Despite the shame, relief programs saved countless lives. They represented a shift in thinking about government’s role in helping citizens during crisis. What started as emergency measures eventually evolved into more permanent social safety net programs.

Penny Auctions

When farms were foreclosed and auctioned, communities sometimes organized penny auctions. Neighbors would bid only pennies for valuable property, then return everything to the foreclosed farmer. This creative resistance helped families keep their land despite bank failures and debt.

Auctioneers and bank representatives who tried to conduct legitimate auctions faced intimidation from crowds determined to help their neighbors. These penny auctions represented community solidarity against financial institutions seen as heartless. People protected each other when the system seemed designed to destroy them.

The tactic showed both desperation and resourcefulness. Legal systems were foreclosing on hardworking families through no fault of their own. Communities responded by gaming the system right back, using the auction process against those wielding it as a weapon.

Living Hand to Mouth

Families lived with zero buffer between earning and eating. Money earned today bought food for tonight—there was nothing left for savings or emergencies. This precarious existence meant any disruption, illness, or unexpected expense could mean disaster.

Parents often skipped meals so children could eat. There was no planning for the future because survival occupied every moment. The phrase captures the immediate desperation of Depression life where the next meal was never guaranteed and planning beyond today was impossible luxury.

Living hand to mouth meant constant anxiety and no security. Families couldn’t think about education, improvement, or dreams—just making it through another day. The psychological weight of this existence was crushing, affecting people’s mental health for years afterward.

Stone Soup Community

Based on the folk tale, stone soup described how communities pooled resources to feed everyone. One family contributed potatoes, another onions, someone else a bit of meat. Separately, no one had enough for a meal, but together they created something sustaining.

Neighborhoods organized communal cooking where families brought whatever they could spare. These gatherings provided not just food but social support during isolating times. People maintained dignity by contributing something, even if just water or seasoning. Everyone ate, and no one went home hungry.

This cooperation showed the best of human nature during the worst times. Communities refused to let neighbors starve when collective action could prevent it. Stone soup became reality—literally creating something from almost nothing through sharing and solidarity.