History books often paint famous people with broad strokes, turning complex individuals into simple characters. Many legendary figures have been reduced to cartoons or myths that miss the real story. Sometimes propaganda, cultural bias, or just catchy rumors have shaped how we remember them. This article explores fifteen historical figures whose true legacies are far more interesting and complicated than the popular versions suggest.

Cleopatra VII (c. 69-30 BC)

Most people picture Cleopatra as nothing more than a beautiful temptress who charmed Roman leaders. That stereotype completely ignores her brilliance and political skill.

She spoke at least nine languages fluently and studied mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy. As Egypt’s ruler, she negotiated treaties, managed the economy, and commanded military forces during incredibly turbulent times.

Her relationships with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony were strategic political alliances, not just romantic affairs. Cleopatra worked tirelessly to preserve Egypt’s independence against the expanding Roman Empire. Popular culture turned this capable monarch into a one-dimensional character, erasing her intellect and leadership. The real Cleopatra was a survivor who used every tool available to protect her kingdom and people.

Genghis Khan (c. 1158-1227)

When people hear the name Genghis Khan, they usually imagine a savage destroyer burning cities without reason. That image misses the sophisticated empire-builder he actually was.

Khan created one of history’s largest empires by implementing revolutionary ideas like promoting people based on talent rather than family background. He established a postal system that connected distant lands and brought stability to trade routes across Eurasia. Religious tolerance was another hallmark of his rule, allowing different faiths to coexist peacefully.

Yes, his military campaigns were brutal by modern standards, but so were most wars of that era. The caricature of mindless violence ignores his organizational genius and the lasting institutions he created. His legacy shaped entire continents for centuries.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821)

Everyone thinks Napoleon was a tiny man with a massive ego who loved war. Actually, he stood about 5 feet 7 inches tall, which was average for French men of his time!

British propaganda exaggerated his shortness to make him seem ridiculous. Beyond the battlefield, Napoleon revolutionized European society through the Napoleonic Code, a legal system that influenced laws worldwide. He reformed education, created efficient government administration, and standardized weights and measures.

His military strategies are still studied in war colleges today because they were genuinely innovative. The cartoon version of Napoleon as a comical warmonger completely overshadows his contributions to modern governance and law. He reshaped Europe in ways that extended far beyond military conquest.

Marie Antoinette (1755-1793)

The phrase “Let them eat cake” has haunted Marie Antoinette’s reputation for centuries, even though she never said it. This false quote made her seem heartless and clueless about her starving subjects.

Marie Antoinette was actually an Austrian princess forced into a political marriage at age fourteen. She arrived in a hostile French court where people resented her foreign origins and blamed her for problems she didn’t cause.

Her spending habits were criticized, but many French nobles lived similarly extravagant lifestyles. The complex politics leading to the French Revolution involved economic disasters, government corruption, and social tensions far beyond one queen’s control. She became a convenient scapegoat for France’s deep-rooted problems, not their actual cause.

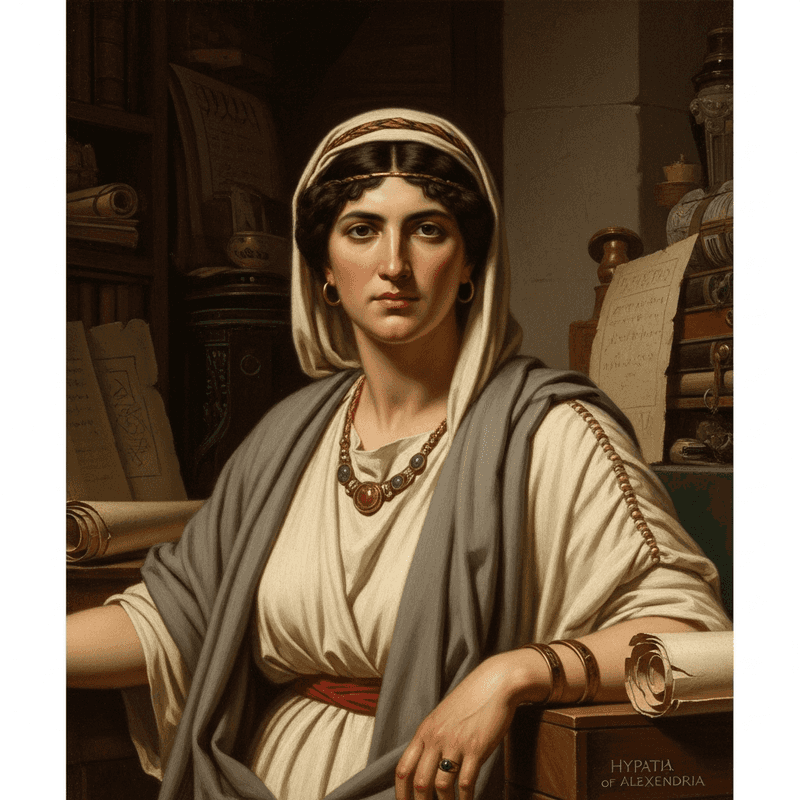

Hypatia of Alexandria (c. 350-415)

Hypatia has been transformed into a symbol of science battling against religious ignorance, but that oversimplifies her actual life. She was indeed a brilliant Neoplatonist philosopher, mathematician, and astronomy teacher in ancient Alexandria.

Her tragic murder by a Christian mob has been interpreted countless ways across different centuries and political movements. Some made her a martyr for reason, others claimed she represented the last gasp of pagan wisdom.

The truth is we have limited reliable historical evidence about her life and work. Much of what people “know” about Hypatia comes from later writers who shaped her story to fit their own agendas. Her real contributions to mathematics and philosophy deserve recognition without the mythological baggage added over time.

Joan of Arc (c. 1412-1431)

Joan of Arc gets remembered as either a simple saint or a fearless war hero, but the reality involves messy medieval politics. This teenage peasant girl claimed to hear divine voices telling her to help France defeat England during the Hundred Years’ War.

Her military successes were real, and she genuinely inspired French troops when morale was desperately low. However, her story also involves nobles using her for political advantage, a rigged trial by enemies, and complicated questions about mental health and religious experience.

French nationalism later embraced her as a symbol, sometimes distorting her actual beliefs and actions. The legend of Joan obscures the frightened young woman facing powerful forces beyond her control. Her courage remains inspiring, but understanding her requires acknowledging the complexity.

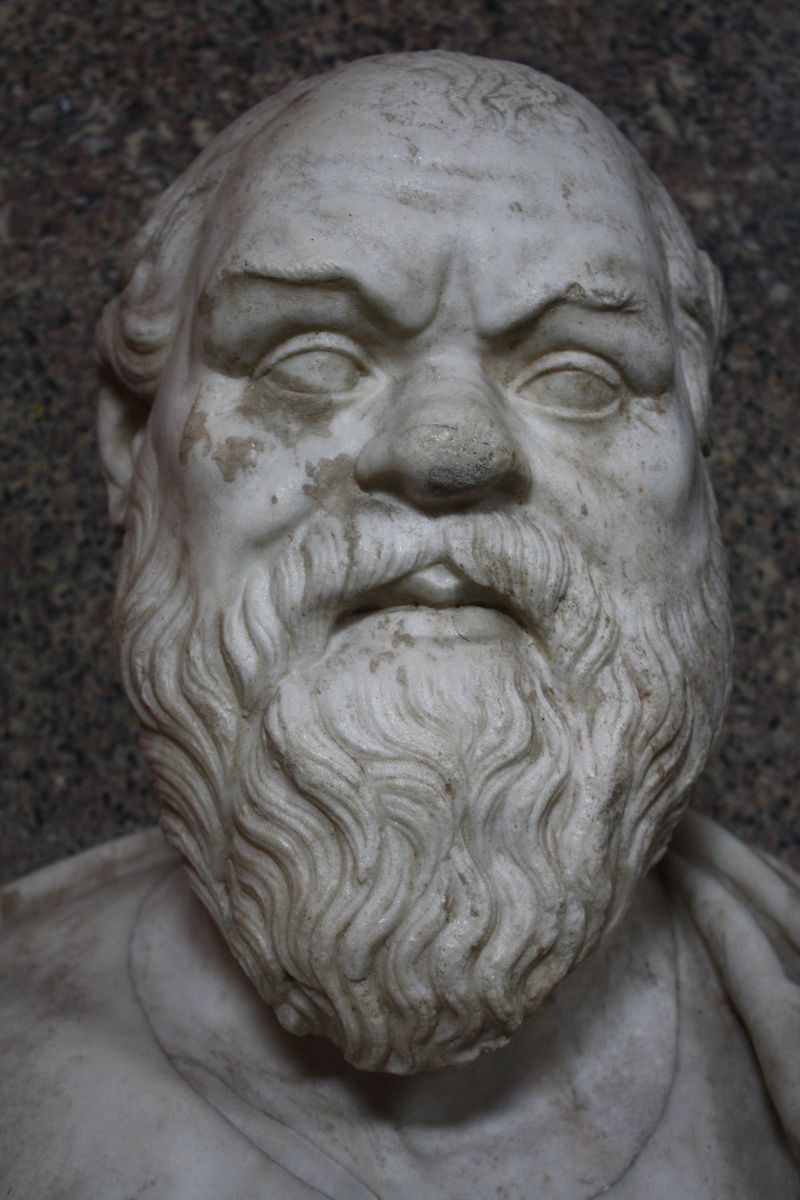

Socrates (c. 469-399 BC)

Picture a wise old teacher in flowing robes calmly discussing philosophy, and you’ve got the popular image of Socrates. That peaceful picture ignores how controversial and annoying he actually was to his fellow Athenians!

His famous Socratic method involved questioning people’s beliefs until they contradicted themselves, which didn’t make him popular at parties. Athenian authorities eventually charged him with corrupting young people and disrespecting the gods.

Rather than accept exile, Socrates chose to drink poison hemlock, turning his death into a philosophical statement. His life was politically dangerous, not just intellectually stimulating. The sanitized version taught in schools misses the risky, rebellious nature of his actual philosophy. Socrates challenged power structures and paid the ultimate price for it.

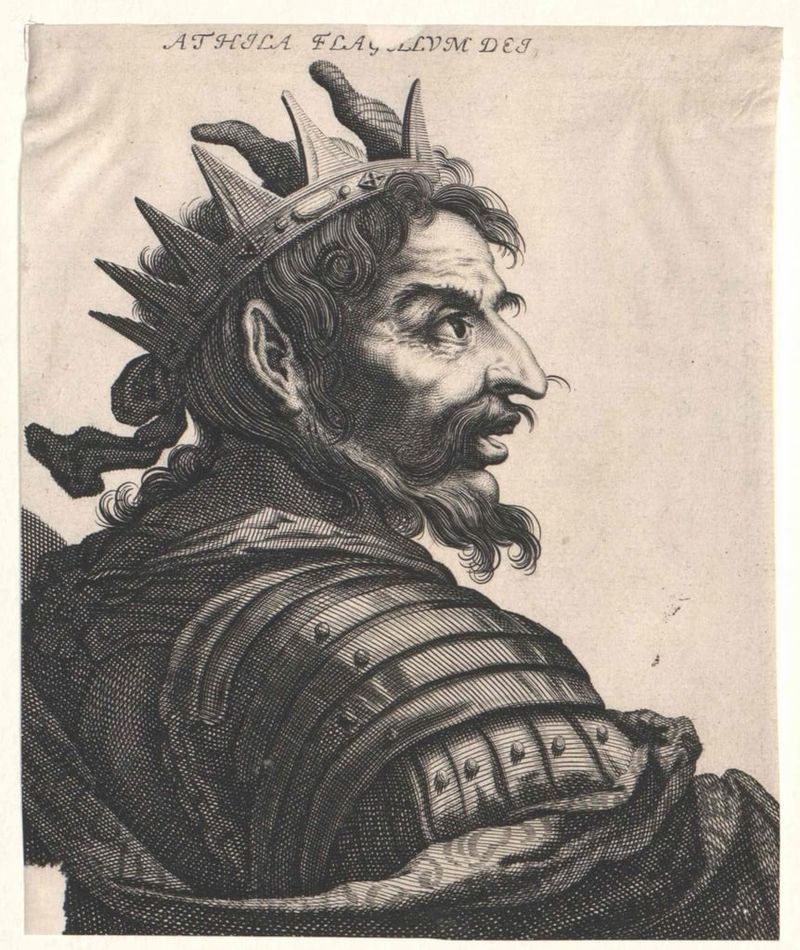

Attila the Hun (c. 406-453)

Roman writers called Attila the “Scourge of God” and painted him as civilization’s nightmare, a savage destroyer on horseback. That propaganda served Roman purposes but ignored the political sophistication of Hun society.

Attila’s military campaigns followed clear strategic goals, not random violence. He negotiated treaties, demanded tribute payments, and played Roman factions against each other with diplomatic skill. His people had complex social structures and trade relationships across vast territories.

The “barbarian” label was mostly Roman fear and prejudice talking. Attila understood power politics as well as any Roman emperor, just from a different cultural perspective. Modern historians recognize that calling him simply a savage tells us more about Roman bias than historical truth.

Empress Wu Zetian (624-705)

China’s only female emperor gets described as ruthless, manipulative, and power-hungry in many historical accounts. Confucian scholars who believed women shouldn’t rule wrote most of these negative descriptions, so their bias is pretty obvious.

Wu Zetian actually implemented important government reforms, promoted officials based on ability rather than family connections, and supported Buddhist temples and cultural projects. Her reign brought relative stability and prosperity to Tang dynasty China.

Yes, she eliminated political rivals, but male emperors did the same thing without being called especially cruel. Recent scholarship shows how gender prejudice shaped her historical reputation more than her actual governing record. She was a capable administrator who broke through impossible barriers in a deeply patriarchal society.

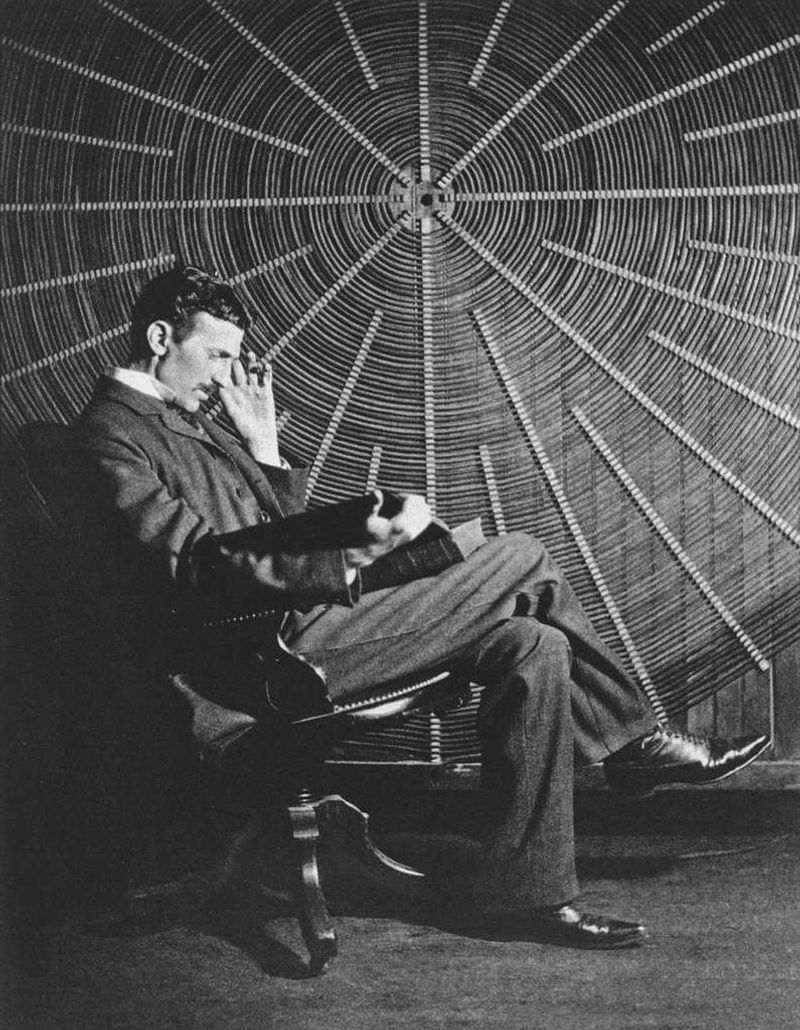

Nikola Tesla (1856-1943)

Tesla has become an internet folk hero, the misunderstood genius supposedly crushed by evil Thomas Edison. While Tesla’s contributions to electrical engineering were genuinely groundbreaking, the mythology around him exaggerates and distorts reality.

He developed alternating current power systems that revolutionized electricity distribution worldwide. His patents and inventions were numerous and important, earning him proper recognition during his lifetime from many scientists.

However, some modern fans credit him with inventions he never made or claim conspiracies suppressed his work. Tesla did face financial difficulties and some ideas didn’t work practically, but that’s normal for inventors. The “mad genius” caricature, whether positive or negative, oversimplifies a talented engineer who had both successes and failures like any human being.

Mary Magdalene (c. 1st Century)

For centuries, Western Christianity portrayed Mary Magdalene as a reformed prostitute, a label that appears nowhere in the actual Gospels. This mistaken identity came from later church leaders conflating different biblical women into one person.

The actual Gospel texts show Mary Magdalene as a prominent disciple of Jesus and the first witness to his resurrection. Early Christian writings suggest she held leadership roles in the movement’s earliest days.

Church politics and patriarchal attitudes probably motivated reducing her to a repentant sinner rather than acknowledging her as an important religious leader. Modern biblical scholarship increasingly recognizes her true significance in early Christianity. The reductive label did enormous damage to understanding her actual historical role and importance.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

Leonardo gets celebrated as the ultimate Renaissance genius who excelled at everything he touched. While his talents were extraordinary, this perfect image glosses over the complicated reality of his life and work.

He left numerous projects unfinished, struggled with patrons who wanted different things than he did, and worked within the political constraints of various Italian city-states. His scientific notebooks contained brilliant observations but also plenty of ideas that didn’t work or weren’t particularly original.

Leonardo worried about money, dealt with professional rivalries, and sometimes produced work mainly because employers demanded it. The mythical version makes him seem superhuman, but the historical Leonardo was a talented person navigating difficult circumstances. Understanding his actual context makes his achievements even more impressive.

Richard III of England (1452-1485)

Shakespeare’s play turned Richard III into a hunchbacked villain who murdered his way to the throne, especially killing his young nephews. That dramatic portrayal served Tudor propaganda purposes since the Tudors overthrew Richard and needed to justify it.

Archaeological discovery of Richard’s skeleton in 2012 showed he had scoliosis but not the severe deformity described in hostile accounts. Historical evidence about the princes’ deaths remains unclear, with no definitive proof Richard ordered their murders.

Many accusations against him came from sources with obvious political motives to make him look terrible. Modern historians recognize that the traditional narrative was heavily shaped by his enemies’ propaganda. Richard’s actual reign was brief and his true character remains genuinely uncertain, buried under centuries of biased storytelling.

Thomas More (1478-1535)

Thomas More wrote “Utopia” and died as a Catholic martyr, which earned him sainthood and a reputation as a principled hero. That heroic portrait leaves out uncomfortable parts of his story that complicate the simple narrative.

As Lord Chancellor, More supported burning heretics and enforced religious conformity harshly. His humanist ideals coexisted with beliefs about religious authority that seem intolerant by modern standards. He was genuinely courageous in refusing to accept King Henry VIII’s break from Rome, even knowing it meant death.

But More’s legacy involves contradictions between his philosophical writings and his political actions. Understanding him requires grappling with how someone could be both a thoughtful intellectual and a harsh enforcer of orthodoxy. Historical figures rarely fit neatly into “good” or “bad” categories.

Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928)

Emmeline Pankhurst led the British suffragette movement with militant tactics that included property destruction and hunger strikes. She’s often remembered simply as a fierce icon of women’s rights.

However, her actual political positions were more complicated, including controversial support for World War I that split the movement. She held class-based views that sometimes conflicted with working-class feminists’ priorities. Her strategic decisions about violence and confrontation sparked genuine debates within feminism about effective tactics.

Pankhurst’s courage and dedication to women’s suffrage were real and important, but the simplified icon version erases the nuanced debates and disagreements that surrounded her leadership. Historical movements involve real arguments and difficult choices, not just heroic unity. Her legacy includes both inspiration and legitimate criticism.