Long before modern technology, Indigenous peoples across the Americas engineered incredible solutions to complex problems. From massive road systems to sustainable farming techniques, these innovations shaped entire civilizations and remain impressive even by today’s standards. Many of these engineering marvels have been forgotten or overlooked, yet they hold valuable lessons for our modern world.

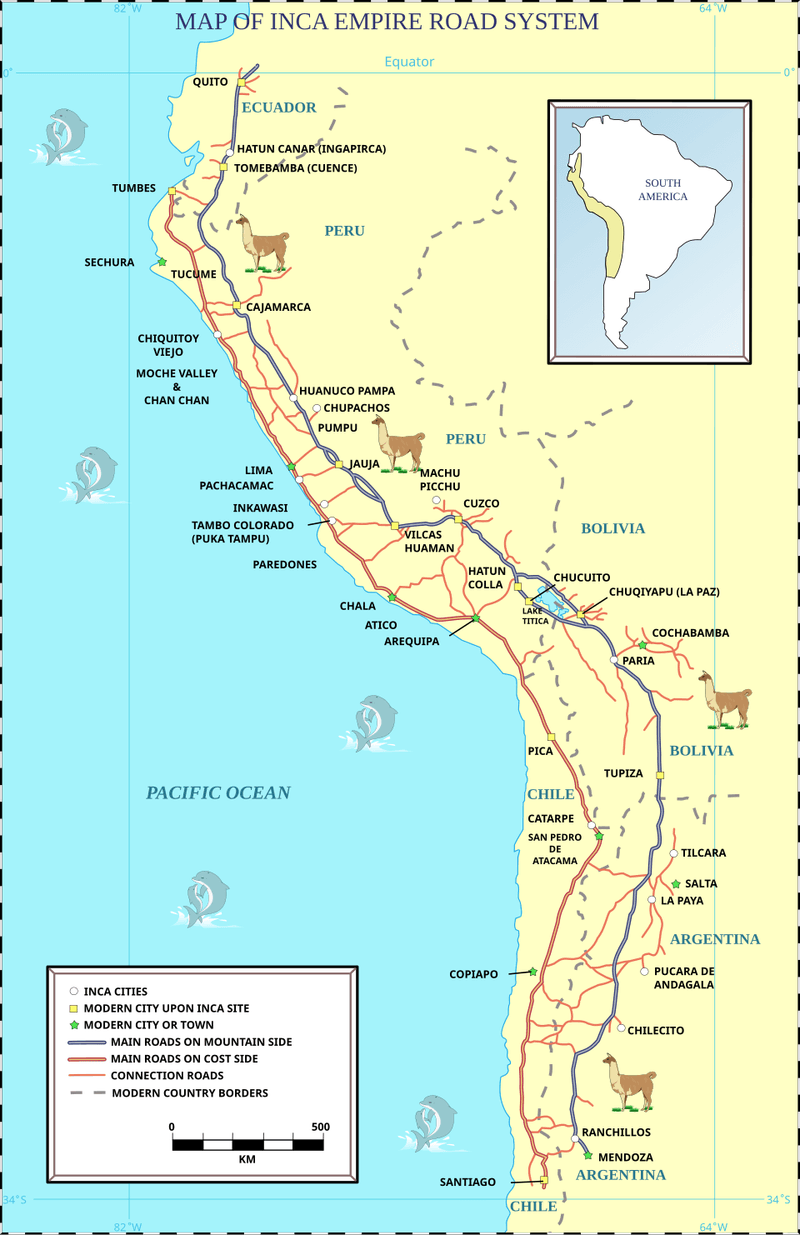

1. The Inca Road System (Andean Region)

Spanning over 25,000 miles across some of the world’s most challenging terrain, the Inca road network stands as one of humanity’s greatest engineering achievements. Built without wheels or iron tools, these roads connected an empire stretching from modern-day Colombia to Chile.

Engineers carved paths through mountains, built tunnels through solid rock, and constructed drainage systems that still function today. Suspension bridges made from woven plant fibers crossed deep gorges, while stone staircases climbed vertical cliff faces.

The roads featured rest stations called tambos every few miles, where travelers could find food and shelter. Many original segments remain intact after 500 years, proving the quality of their construction. Modern highway engineers study these ancient routes to understand their remarkable durability and intelligent design principles.

2. Rope Suspension Bridges (Peru – Quechua)

High in the Peruvian Andes, communities once connected isolated villages with bridges made entirely from grass. These weren’t simple structures but sophisticated engineering feats that could support hundreds of people and pack animals simultaneously.

Woven from ichu grass using techniques passed down through generations, each bridge required precise tension calculations and material knowledge. The fibers were twisted into cables thicker than a person’s arm, then anchored to massive stone foundations on each side of the gorge.

What makes this even more remarkable is the maintenance system. Every year, entire communities gathered to rebuild their bridge in a festival called Q’eswachaka, replacing old fibers before they weakened. This tradition continues today at one remaining bridge, keeping alive an engineering practice that’s over 500 years old.

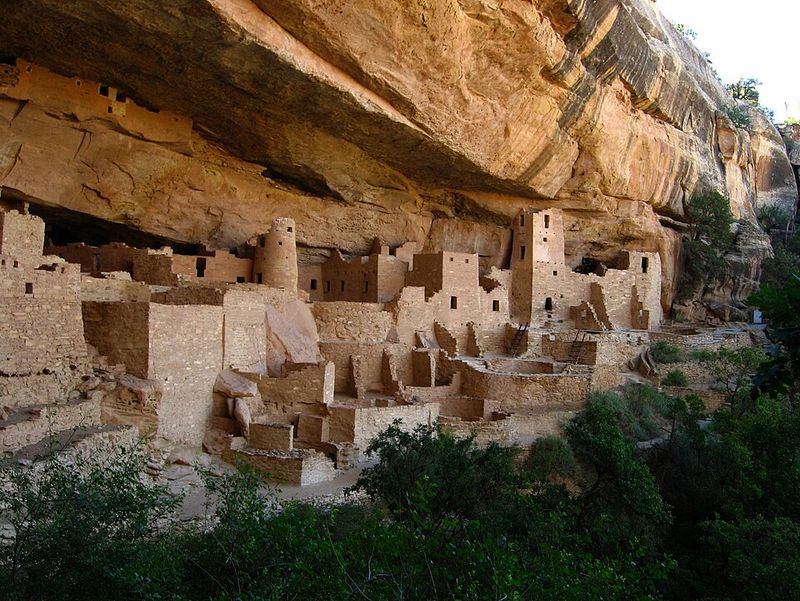

3. Cliff Dwellings of the Ancestral Puebloans (Southwest U.S.)

Imagine building an entire apartment complex on the side of a cliff using only stone tools and your bare hands. That’s exactly what the Ancestral Puebloans accomplished between 1190 and 1300 CE in places like Mesa Verde.

These weren’t random caves with some walls added. Engineers carefully selected alcoves that provided natural shelter from rain and snow while capturing winter sunlight for warmth. They mixed mortar from clay, water, and ash that has held stones together for over 700 years.

The buildings featured multiple stories, with rooms designed for specific purposes like storage, living quarters, and ceremonial spaces. Passive solar design kept interiors comfortable year-round without any mechanical heating or cooling. Some structures contained over 150 rooms and housed entire communities protected from both weather and potential threats.

4. Cahokia’s Monks Mound (Mississippi River Valley)

Rising over 100 feet above the Mississippi River floodplain, Monks Mound represents North America’s largest pre-Columbian earthwork. Constructed between 900 and 1200 CE, this artificial mountain covers 14 acres at its base and contains approximately 22 million cubic feet of soil.

Every basket of dirt was carried by hand, yet the structure shows sophisticated engineering planning. The mound’s four terraced levels align precisely with cardinal directions, suggesting advanced surveying knowledge. Engineers designed drainage systems to prevent erosion and selected different soil types for specific structural purposes.

The summit once supported a massive wooden building that served as either a temple or the residence of Cahokia’s leaders. At its peak, Cahokia was larger than London, with a population estimated at 20,000 people. The mound’s stability after nearly 1,000 years proves the builders understood soil mechanics and long-term structural integrity.

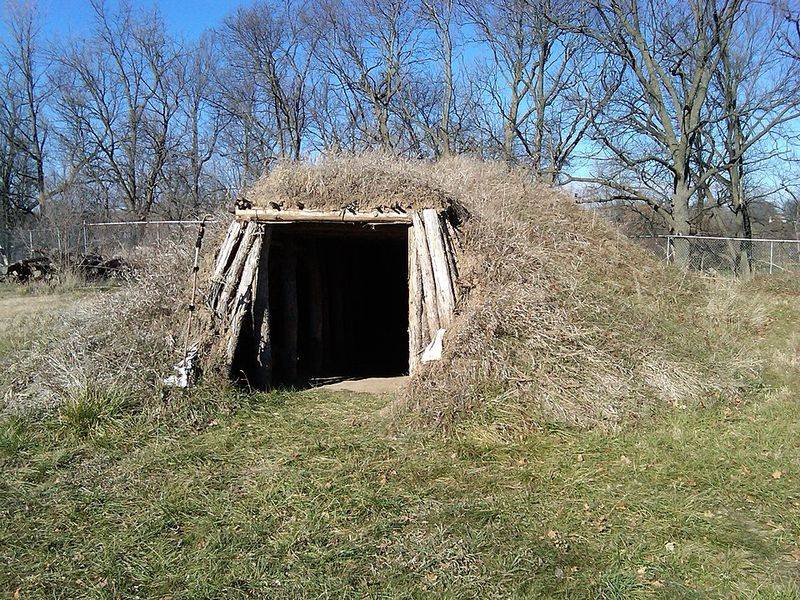

5. Earth Lodges and Thermal Insulation (Plains Tribes)

Plains tribes engineered homes that would make modern green architects jealous. Earth lodges combined timber framing with thick layers of grass and soil to create structures that maintained comfortable temperatures year-round without any external energy source.

The secret lay in thermal mass. By building partially underground and covering walls with two to three feet of earth, these homes absorbed heat slowly during summer days and released it at night. In winter, the same principle worked in reverse, keeping interiors warm even during blizzards.

A central fire pit provided additional heating, with smoke escaping through a carefully positioned opening that also allowed light to enter. The circular design distributed structural loads evenly, making the lodges incredibly stable. Some measured up to 60 feet in diameter and housed extended families comfortably for decades with minimal maintenance required.

6. Hohokam Canals (Arizona)

Between 600 and 1450 CE, the Hohokam people transformed Arizona’s harsh Sonoran Desert into productive farmland through one of the most extensive irrigation systems in the ancient Americas. Their canal network stretched over 500 miles, delivering water to thousands of acres of crops.

The engineering precision required is staggering. Canals had to maintain exact gradients so water flowed steadily without eroding channel walls or depositing too much sediment. Too steep, and the canals would wash out; too shallow, and water wouldn’t flow far enough.

Archaeologists discovered that Hohokam engineers achieved gradients within fractions of a degree, comparable to modern standards. They built headgates to control water distribution, weirs to manage flow rates, and settling basins to remove sediment. Some canals are still visible today, and portions of Phoenix’s modern canal system follow the same routes the Hohokam established over 1,000 years ago.

7. Aztec Chinampas (Mexico)

Called floating gardens, chinampas were actually anchored agricultural platforms that produced some of the highest crop yields in human history. Built in shallow lakes around the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, these engineered islands transformed swampland into incredibly productive farmland.

Construction began by staking out rectangular plots in shallow water, then filling them with alternating layers of mud, decaying vegetation, and lake sediment. Willow trees planted along the edges sent roots deep into the lake bed, anchoring the entire structure permanently.

The system was brilliantly efficient. Farmers could harvest up to seven crops per year because the surrounding water provided constant irrigation and the rich lake-bottom mud supplied endless nutrients. Canals between chinampas served as highways for canoes transporting produce to market. Some chinampas in Xochimilco still produce flowers and vegetables today, nearly 700 years after their construction.

8. Maya Water Filtration Systems

Recent archaeological analysis revealed that the Maya weren’t just collecting water; they were purifying it using methods remarkably similar to modern treatment systems. At Tikal, one of their largest cities, researchers discovered evidence of sophisticated filtration technology dating back over 2,000 years.

Engineers lined reservoir walls with layers of quartz sand and zeolite, a crystalline mineral that naturally removes harmful microbes and heavy metals. Water percolating through these layers emerged clean and safe to drink, solving a critical challenge in a region with seasonal droughts.

What’s truly impressive is that zeolite doesn’t occur naturally near Tikal. Maya engineers had to identify this material’s purification properties, then transport it from sources over 20 miles away. Modern water treatment plants use zeolite for the exact same purpose. This discovery has fundamentally changed how archaeologists view ancient American engineering capabilities and scientific knowledge.

9. Inuit Snow Block Architecture

An igloo isn’t just a pile of snow blocks; it’s a precisely engineered dome that demonstrates sophisticated understanding of structural mechanics and thermodynamics. Built in environments where temperatures plunge to minus 40 degrees, these shelters could maintain interior temperatures around 40 degrees Fahrenheit using only body heat.

The secret lies in the spiral construction technique. Each snow block is cut at a specific angle and placed in a continuously rising spiral that creates a self-supporting dome. This distributes weight evenly across the entire structure, preventing collapse even under heavy snow accumulation.

Snow itself provides remarkable insulation because trapped air pockets prevent heat transfer. Builders selected snow with the right density and crystal structure, testing it like modern engineers test concrete. A properly built igloo could be warmed to comfortable temperatures with a single small seal oil lamp, and some were large enough to house multiple families with separate rooms.

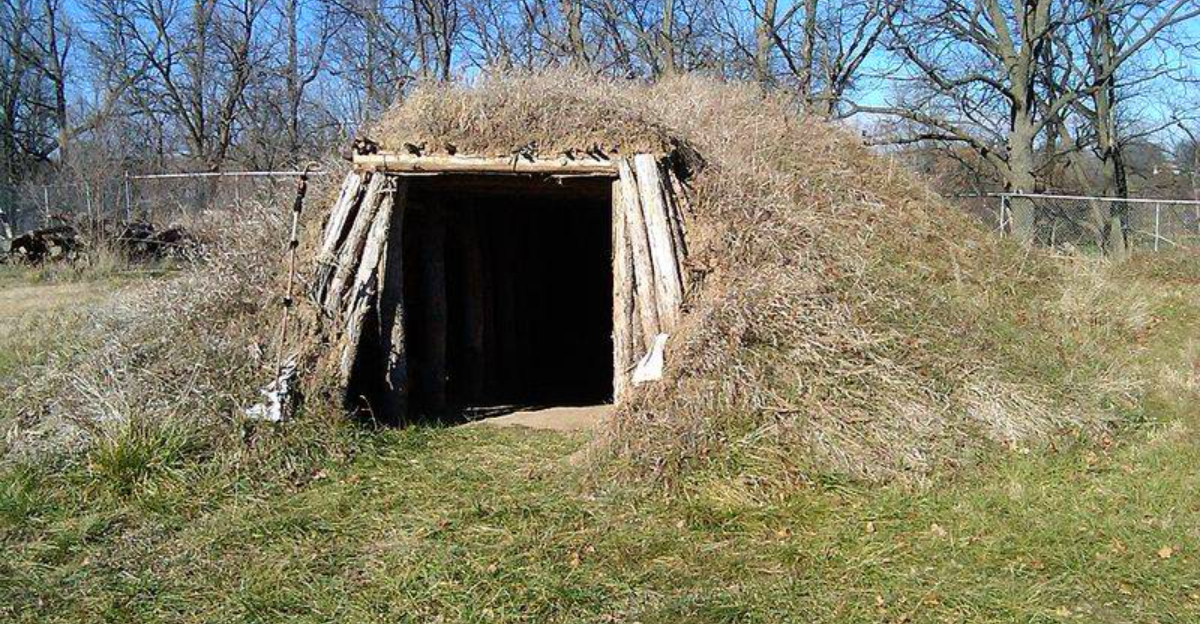

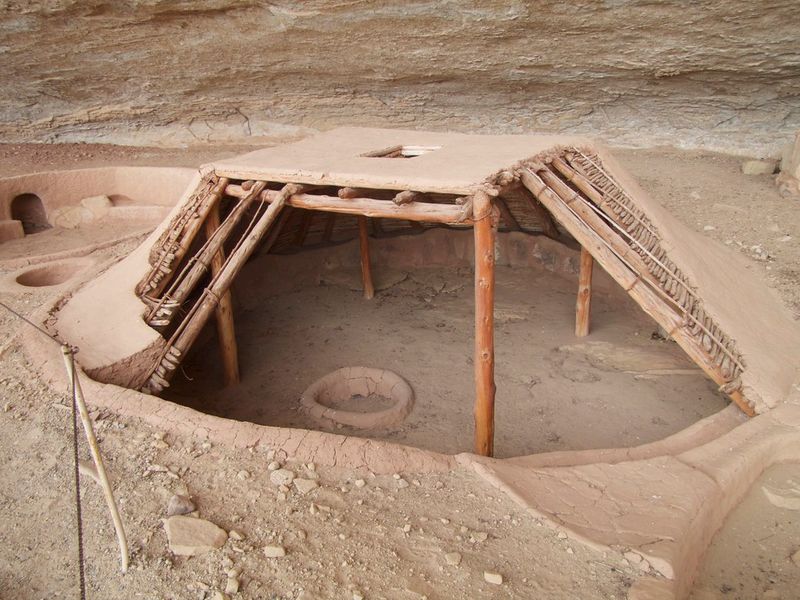

10. Pit Houses with Passive Airflow (Pacific Northwest & Plateau Tribes)

Tribes across the Pacific Northwest and Plateau regions engineered homes that heated and ventilated themselves using nothing but physics. These pit houses, built partially underground, incorporated natural convection to create comfortable living spaces in all seasons.

Construction began by excavating several feet into the earth, which provided natural insulation and protection from wind. A timber and earth roof covered the pit, with a central opening serving multiple purposes: entrance, smoke outlet, and ventilation shaft.

The genius was in the airflow design. Cool, fresh air entered through low openings near the floor, warmed as it passed by the central fire, then rose naturally to exit through the roof opening. This created a continuous air circulation that removed smoke efficiently while maintaining warmth. In summer, the same system provided cooling. Archaeological evidence shows some pit houses were occupied continuously for over 100 years, testament to their durability and comfort.

11. Inuit Kayak Design

When naval architects analyze traditional Inuit kayaks, they find a vessel so perfectly designed for its purpose that modern versions have changed remarkably little. These boats represent centuries of engineering refinement, with every curve and dimension serving a specific hydrodynamic function.

Built from driftwood frames covered with stretched sealskin, kayaks were custom-fitted to each hunter like a wetsuit. The narrow beam and low profile reduced wind resistance while the sharp bow cut through waves efficiently. The design provided exceptional speed and maneuverability while remaining stable enough for hunting in rough Arctic waters.

Different regions developed specialized variants: wider for stability in open ocean, narrower for speed in calm waters, or with upturned bows for navigating through ice. The waterproof seal between the hunter’s parka and the cockpit opening created a unit that could roll completely over and resurface. Modern recreational kayaks, racing shells, and even some military craft still copy these fundamental design principles.

12. Haudenosaunee Longhouse Construction

Haudenosaunee longhouses were architectural marvels that could stretch over 200 feet in length and house up to 20 families under one roof. Built entirely without nails or metal fasteners, these structures relied on sophisticated joinery and an understanding of wood properties that modern carpenters admire.

Construction began by setting rows of young trees into the ground, then bending them overhead to create a barrel-vaulted ceiling. Cross-members lashed with plant fiber cordage provided structural support, while sheets of elm bark formed weatherproof walls and roofing.

The interior design showed remarkable planning. A central corridor ran the length of the building with fire pits spaced evenly for cooking and heating. Smoke holes in the roof aligned with each fire pit, and could be adjusted using movable bark panels to control draft. Sleeping platforms lined both walls, creating private family spaces within the communal structure. These buildings lasted 20 to 30 years before needing replacement, impressive for organic materials in harsh northeastern winters.

13. Tarahumara Trail Engineering (Copper Canyon, Mexico)

The Rarámuri people, often called Tarahumara, engineered trail systems through Mexico’s Copper Canyon region that put modern hiking paths to shame. These aren’t gentle woodland walks but steep routes carved into sheer cliff faces that climb thousands of vertical feet through some of North America’s most dramatic terrain.

Trail builders used precisely calculated switchbacks to make impossible grades manageable. They positioned steps at ergonomic heights and carved handholds into rock faces where necessary. Water drainage was incorporated into the design so trails wouldn’t wash out during heavy rains.

What makes these trails even more remarkable is their purpose. The Rarámuri are famous for their long-distance running abilities, and these trails enabled them to travel rapidly between canyon settlements. Runners could cover over 100 miles in a single day on these paths, carrying messages and trade goods. Modern ultramarathon runners train on these same trails, marveling at the engineering that makes such extreme athletic feats possible.

14. Chaco Canyon Roads (Southwest U.S.)

The road system radiating from Chaco Canyon in New Mexico defies easy explanation. These aren’t simple trails worn by foot traffic but engineered highways up to 30 feet wide, cut through solid rock in places, that run in perfectly straight lines for miles regardless of terrain.

What puzzles archaeologists is that they sometimes go directly over mesas and cliffs rather than around them, requiring stairs to be carved into rock faces. The roads connect to outlying communities and significant sites, but their width seems excessive for a culture without wheeled vehicles or pack animals.

Construction required sophisticated surveying to maintain such straight alignments over long distances. Workers removed all vegetation and often excavated down to bedrock, then edged the roads with stone borders. Some sections show evidence of paving. The roads’ purpose remains debated, with theories ranging from ceremonial pathways to trade routes to astronomical alignments. Regardless, they represent engineering capabilities and organizational power that challenge previous assumptions about Ancestral Puebloan society.

15. Amazonian Terra Preta (South America)

Hidden beneath the Amazon rainforest lies evidence of perhaps the most remarkable agricultural innovation in human history. Terra preta, or black earth, is an engineered soil that remains incredibly fertile centuries after its creation, unlike any naturally occurring tropical soil.

Indigenous Amazonians created this super-soil by mixing charcoal, pottery shards, animal bones, and organic waste into the ground. The charcoal acts as a habitat for beneficial microorganisms while holding nutrients and water. This biochar remains stable for thousands of years, continuously improving soil quality.

Modern agriculture strips tropical soils of nutrients within a few growing seasons, but terra preta actually regenerates itself. Scientists studying these soils have found they’re two to three times more fertile than surrounding jungle earth. Some plots created over 2,000 years ago are still more productive than regular farmland. Researchers now study terra preta as a potential solution to modern agricultural challenges and even as a method for carbon sequestration to combat climate change.

16. The Adena and Hopewell Geometric Earthworks (Ohio Valley)

Between 200 BCE and 500 CE, Adena and Hopewell cultures constructed earthworks in the Ohio Valley that rival Stonehenge in their astronomical precision and geometric perfection. These weren’t simple burial mounds but complex geometric shapes: perfect circles up to 1,200 feet in diameter, precise squares, and elaborate octagonal forms.

The engineering precision is astounding. Modern surveys using laser technology have confirmed that these ancient earthworks achieve near-perfect geometric shapes. The circles are round to within inches over their entire circumference, and the squares have corners at exactly 90 degrees.

Many earthworks align with lunar and solar events like solstice sunrises and the 18.6-year lunar cycle. Creating such precise geometry over such large areas required advanced surveying equipment and mathematical knowledge. The amount of earth moved, all carried in baskets, represents millions of hours of coordinated labor. Some sites cover hundreds of acres and would have taken generations to complete, suggesting sophisticated social organization and long-term planning capabilities.

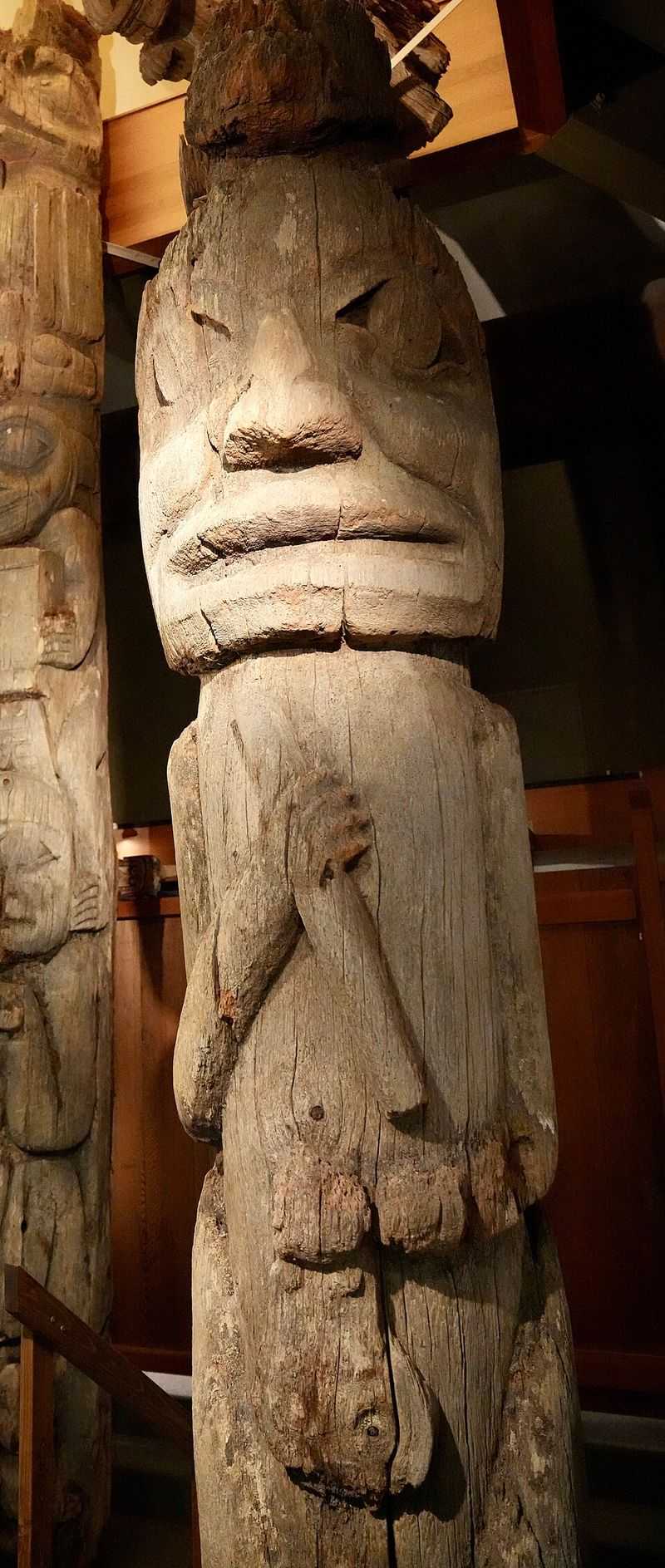

17. Tlingit and Haida Totem Engineering

Standing up to 60 feet tall, totem poles represent not just artistic achievement but sophisticated engineering that enabled massive cedar logs to remain standing for over a century in one of the world’s wettest climates. Creating these monuments required understanding wood properties, structural balance, and preservation techniques.

Carvers selected specific cedar trees for their straight grain and natural rot resistance. They understood that carving the pole while the wood was still green made the work easier, but they had to account for how the wood would shrink and crack as it dried.

The engineering challenge was maintaining balance. Carvers removed tons of wood from the original log, changing its weight distribution. They had to calculate exactly where to position each carved figure so the finished pole would stand vertically without leaning. Controlled burning techniques were used to hollow sections, reducing weight while maintaining strength. The poles were then erected in holes engineered for stability, sometimes with elaborate raising ceremonies involving dozens of people and sophisticated rope and lever systems.

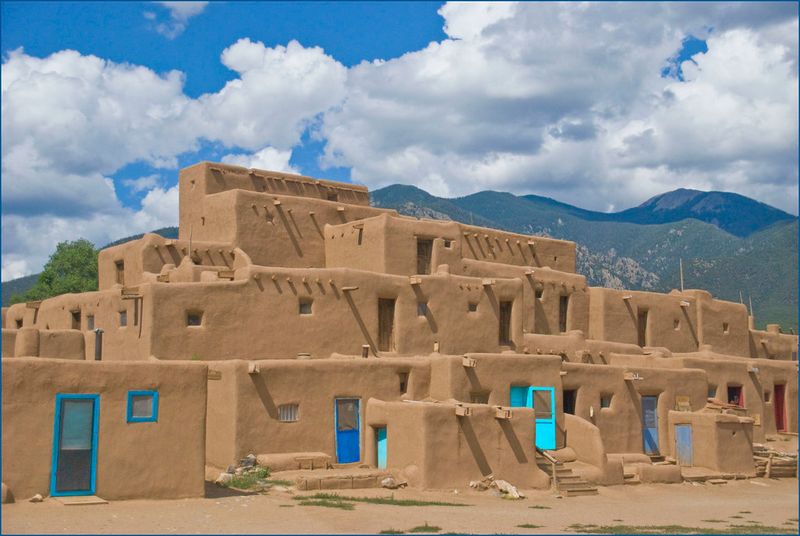

18. Puebloan Multistory Apartments

Taos Pueblo in New Mexico has been continuously inhabited for over 1,000 years, making it one of the oldest apartment complexes in North America. These multistory adobe structures weren’t built all at once but represent generations of engineering knowledge refined over centuries.

The construction method uses adobe bricks made from clay, sand, straw, and water, dried in the sun. Walls are several feet thick at the base, providing tremendous thermal mass that moderates temperature swings. The buildings step back as they rise, creating terraced levels accessed by wooden ladders.

This design serves multiple purposes: it provides rooftop workspace, creates defensible positions, and ensures upper levels don’t overload lower walls. Builders understood load distribution and constructed walls that taper from thick bases to thinner upper sections. The adobe requires regular maintenance, with new layers of mud plaster applied annually, but this actually strengthens the structure over time. Modern architects study these buildings as examples of sustainable construction that lasts centuries with minimal environmental impact.

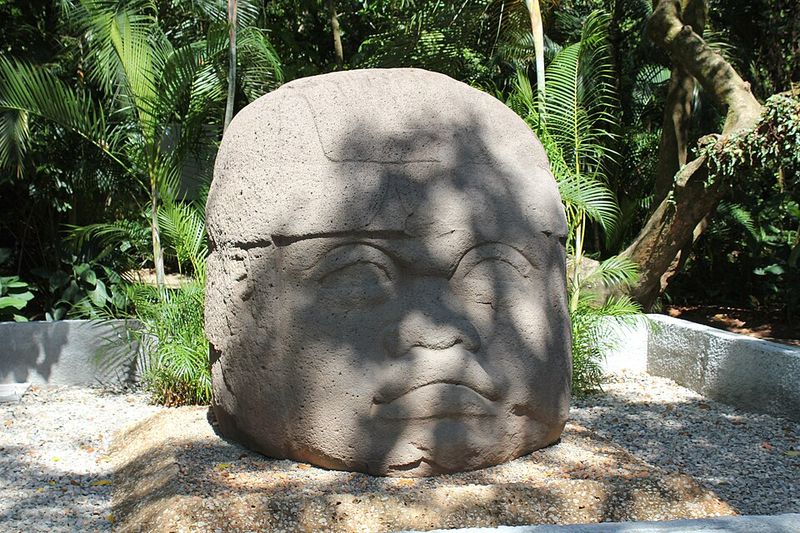

19. Olmec Basalt Transport

The Olmec civilization created colossal stone heads weighing up to 40 tons each, carved from single basalt boulders. The engineering mystery is how they transported these massive sculptures over 70 miles from mountain quarries to their final locations without wheels, metal tools, or draft animals.

Recent archaeological research suggests a combination of techniques. Workers probably used stone tools to shape log rollers, creating a temporary road surface. During rainy seasons, they may have floated the heads on rafts down rivers, taking advantage of seasonal flooding.

The organizational challenge was enormous. Moving a 40-ton stone head would require hundreds of workers pulling in coordination, with engineers managing the route, solving problems, and ensuring the sculpture didn’t crack or tip during transport. The fact that Olmec sites contain multiple colossal heads proves they solved this engineering challenge repeatedly. Modern attempts to recreate the process using only period-appropriate technology have succeeded but required extensive planning and dozens of people working for weeks to move similar weights even short distances.

20. The Métis Red River Cart (Great Plains & Canada)

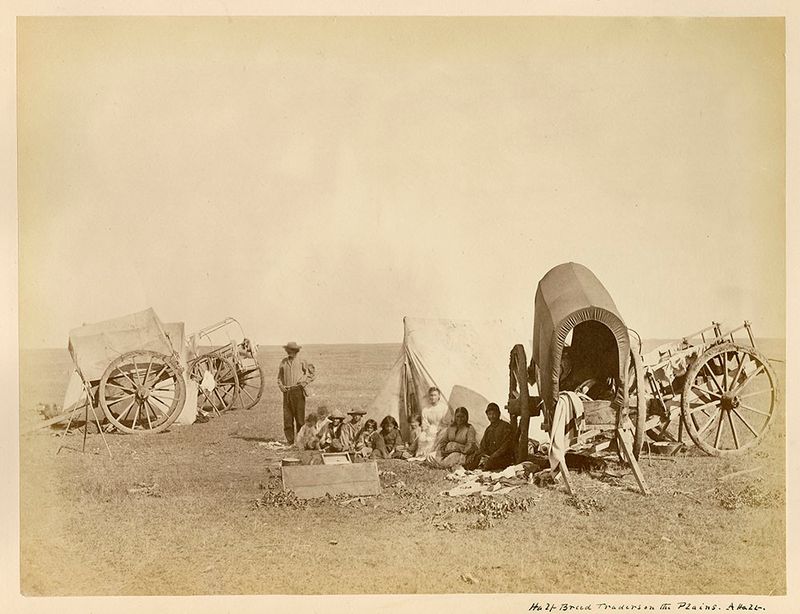

The Red River cart represents elegant engineering problem-solving. Built entirely from wood without a single metal part, these carts could carry 1,000 pounds of cargo across roadless prairies and transform into rafts for river crossings.

Métis craftsmen constructed the carts using only axe, saw, and knife. Large wheels, sometimes five feet in diameter, distributed weight to prevent sinking in mud or soft ground. The axle was fixed to the frame, so the wheels turned on the axle, creating the cart’s famous squealing sound that could be heard for miles.

The genius was in the design’s versatility. When travelers reached a river, they could remove the wheels, lash them to the sides of the cart body, and float the whole thing across like a raft. Because no metal parts would rust, carts could be submerged repeatedly without damage. The all-wood construction also meant repairs could be made anywhere using available materials. These carts became the primary freight vehicle across the northern plains for decades, moving millions of pounds of furs and trade goods.

21. Pottery Kiln Innovations (Southwest & Mexico)

Long before modern kilns, tribes like the Ancestral Puebloans and Mogollon developed firing techniques that produced ceramic vessels of remarkable quality and durability. Their outdoor kilns achieved controlled temperatures high enough to create pottery that has survived intact for over 1,000 years.

The process involved constructing temporary kilns from stones and clay, stacking pottery inside, then covering everything with a carefully arranged fuel layer. Potters controlled temperature by adjusting fuel type, airflow, and firing duration. They understood that different clay compositions required different firing temperatures and atmospheres.

Some cultures developed sophisticated reduction firing techniques, where limiting oxygen during firing produced distinctive black pottery. Others mastered oxidation firing that created vibrant reds and oranges. The engineering knowledge required included understanding combustion, heat transfer, and material properties. Potters had to calculate proper vessel thickness to prevent cracking, formulate clay mixtures with the right temper materials, and time the cooling process to avoid thermal shock. The results were vessels so well-made that museums worldwide display them as both functional objects and artistic masterpieces.