The northern and southern lights have been putting on quite a show lately, and scientists say we’re in for more dazzling displays as the Sun ramps up its activity. While these glowing curtains of color are beautiful to watch, they’re also a sign that powerful space weather is hitting Earth’s magnetic shield.

What many people don’t realize is that the same solar storms that create those stunning auroras can also mess with satellites, GPS signals, radio communications, and even power grids. Understanding what’s happening high above our heads can help us appreciate the science behind the spectacle and stay aware of the surprising tech side effects that come along for the ride.

1. A ‘solar storm’ isn’t one thing – it’s a bundle of space-weather events

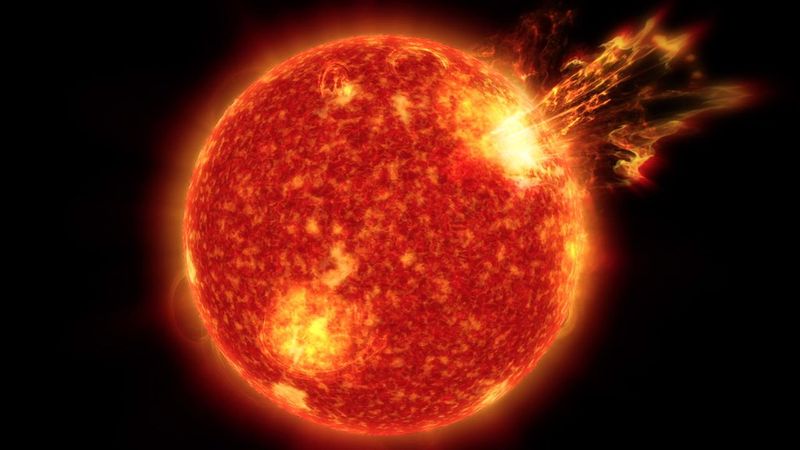

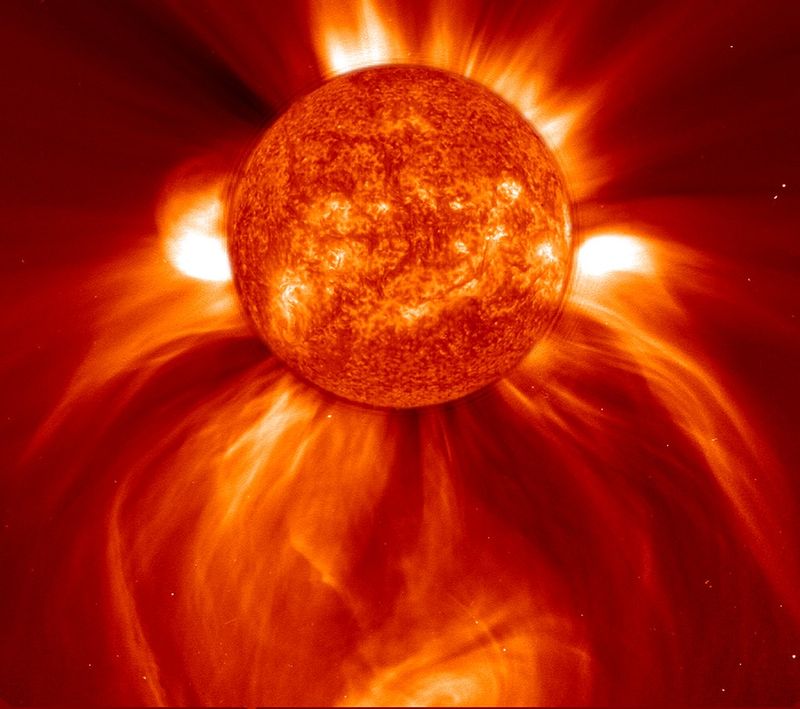

A cosmic combo platter: that’s what experts mean when they talk about a solar storm. When people say “solar storm,” they’re often lumping together different phenomena that can happen around the same time: solar flares, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), and enhanced solar radiation.

Each affects Earth differently.

Solar flares are like giant flashbulbs going off on the Sun’s surface, sending out bursts of energy that can reach us in just minutes. CMEs are massive clouds of charged particles that get hurled into space and take longer to arrive but pack a much bigger punch when they do.

Enhanced solar radiation refers to streams of high-energy particles that can flood certain regions of space.

All three can occur during the same solar event, but they don’t always travel together or hit us at the same time. That’s why forecasters track each component separately.

Understanding this bundle helps scientists predict which technologies might be at risk and when. So next time you hear “solar storm,” remember it’s really shorthand for a whole package of space weather happening at once, each with its own timeline and impact.

2. Solar flares are the flash – fast, bright, and good at disrupting radio

A solar flare is a sudden burst of energy from the Sun. Imagine the biggest explosion you can think of, then multiply it by millions.

These flares release intense radiation across the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to X-rays and gamma rays.

The big immediate impact for Earth is usually on radio communications (especially on the sunlit side of the planet), because flares can trigger “radio blackouts” by altering the ionosphere. The ionosphere is a layer of Earth’s atmosphere filled with charged particles that normally helps radio signals bounce around the planet.

When a flare’s radiation hits, it can change the ionosphere’s properties in minutes, making certain radio frequencies unusable.

Pilots, ham radio operators, and emergency services that rely on high-frequency radio can suddenly find their signals garbled or completely silent. The good news is that radio blackouts from flares are usually short-lived, lasting from minutes to a few hours.

Once the flare’s radiation stops bombarding the ionosphere, normal radio propagation gradually returns. Still, those brief disruptions can be a real headache for anyone depending on clear communications during critical moments.

3. CMEs are the ‘push’ – huge clouds that can slam into Earth’s magnetic shield

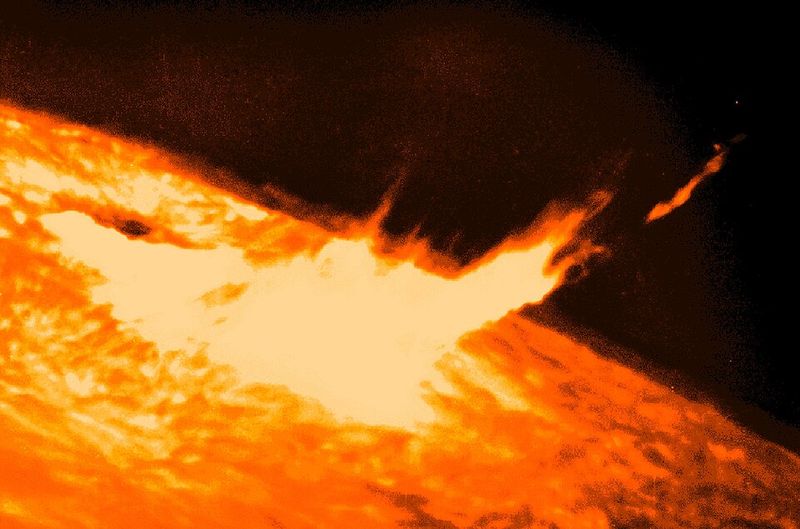

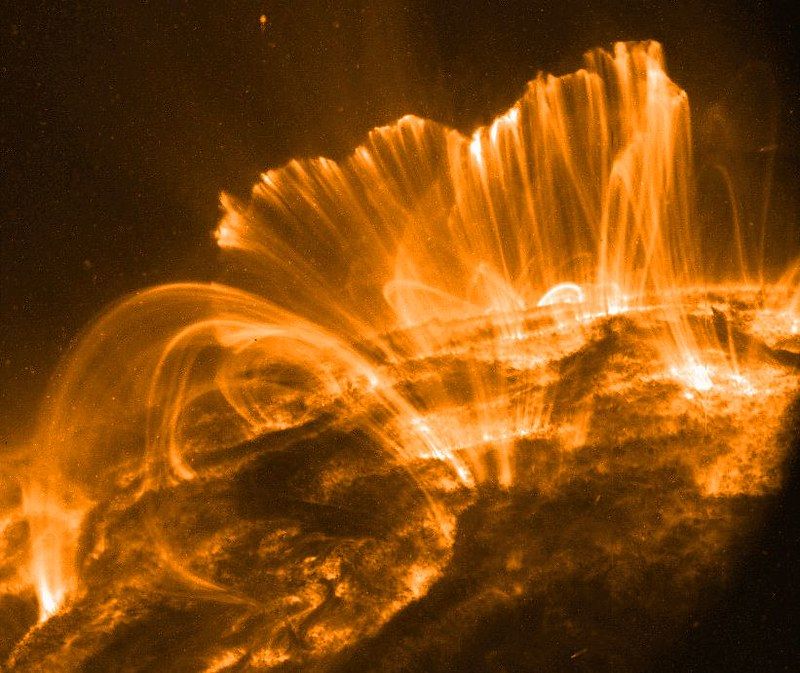

A coronal mass ejection is a large expulsion of plasma and magnetic field from the Sun’s corona. Think of it as the Sun sneezing out a billion-ton bubble of electrified gas.

CMEs can travel extremely fast (hundreds to thousands of km/s) and, if aimed at Earth, can be the main driver of major geomagnetic storms.

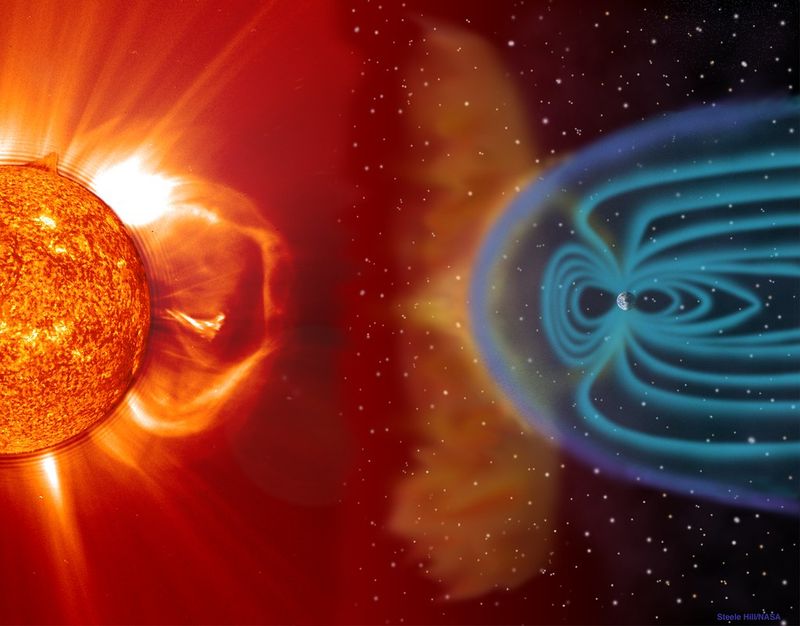

Unlike flares, which arrive at the speed of light, CMEs take time to reach us—anywhere from about 15 hours to several days, depending on their speed. When a CME slams into Earth’s magnetosphere (our planet’s magnetic shield), it can compress and distort the field, loading it with energy.

That energy doesn’t just disappear; it gets released in bursts that power auroras and can also induce electrical currents in the ground and in space.

Not every CME hits Earth. The Sun throws them off in all directions, and only the ones aimed our way matter.

Scientists use spacecraft positioned between the Sun and Earth to measure incoming CMEs and refine their forecasts. The faster and more magnetically aligned a CME is, the bigger the potential impact on our technology and infrastructure.

4. The biggest aurora nights usually come from geomagnetic storms

When a CME (or strong solar wind) couples efficiently with Earth’s magnetosphere, it loads energy into the system. When that energy gets released, it can turbocharge auroras and also create disturbances that affect technology.

Geomagnetic storms are the result of this energy transfer, and they’re rated on a scale from minor to extreme.

During a strong geomagnetic storm, Earth’s magnetic field lines get stretched and twisted like rubber bands. When they snap back, they accelerate particles toward the poles, where those particles collide with atmospheric gases and light up the sky.

The stronger the storm, the more energy is available, and the brighter and more widespread the auroras become.

But the same magnetic turbulence that makes auroras spectacular also induces currents in power lines, pipelines, and other long conductors. Satellites can experience charging problems, and radio signals can scatter unpredictably.

So while a G4 or G5 geomagnetic storm might give you an unforgettable light show, it’s also a time when grid operators, satellite controllers, and航空 authorities are on high alert, watching their systems closely for any signs of trouble.

5. G1 to G5 is a real scale, and G5 is genuinely rare

NOAA’s geomagnetic storm scale runs from G1 (minor) to G5 (extreme). G5 storms are uncommon – on the order of a handful per ~11-year solar cycle, not something you see every month.

Each step up the scale represents a significant increase in the storm’s intensity and potential impacts.

G1 storms are relatively mild and might cause minor fluctuations in power grids or slight disturbances to satellite operations. G2 and G3 storms can lead to voltage alarms in power systems and require some corrective actions.

G4 storms start to cause widespread issues, including possible transformer damage and disruptions to GPS and radio communications.

Then there’s G5, the top of the scale. A G5 event can trigger widespread power system problems, including potential blackouts in some areas.

Satellite operations can be severely affected, and high-frequency radio communications can be almost completely blacked out in certain regions. Historically, extreme storms like the Carrington Event of 1859 or the March 1989 storm that knocked out power in Quebec fall into this category.

Because G5 storms are so rare, each one becomes a major event that scientists study for years afterward.

6. Auroras happen when solar particles excite gases in our atmosphere

In simple terms: charged particles get guided by Earth’s magnetic field toward high latitudes, collide with atmospheric gases, and those gases emit light. That’s why auroras aren’t “weather” like clouds—they’re space physics happening above the weather.

The whole process takes place between about 60 and 200 miles above Earth’s surface, well above where airplanes fly and where rain or snow forms.

When a solar particle (usually an electron or proton) smacks into an oxygen or nitrogen molecule, it transfers energy to that molecule. The molecule gets excited—meaning its electrons jump to higher energy levels.

When those electrons drop back down to their normal state, they release the extra energy as light. Different gases and different energy levels produce different colors.

Earth’s magnetic field acts like a giant funnel, channeling particles toward the poles. That’s why auroras are most commonly seen at high latitudes, near the Arctic and Antarctic circles.

The whole display is a visible reminder that we live inside a protective magnetic bubble, and that space isn’t as empty or calm as it might seem from the ground.

7. Aurora colors aren’t random – they depend on altitude and which gas is hit

Different atmospheric gases (and different altitudes) produce different colors. That’s why auroras can shift from green to red to purple as conditions change.

Oxygen is the star player in most aurora displays. At lower altitudes (around 60 to 150 miles up), oxygen emits a bright green light, which is the most common aurora color people see.

Higher up, around 150 to 200 miles, oxygen can produce a rare deep red glow. Nitrogen, on the other hand, tends to create blue or purplish-red hues, depending on whether the nitrogen molecules are ionized or just excited.

The mix of colors you see in any given aurora depends on the altitude where the collisions are happening, the types of gases present at that altitude, and the energy of the incoming particles.

Sometimes you’ll see auroras that look like they have distinct layers of color, almost like a rainbow. That’s because different altitudes are being hit simultaneously, each contributing its own signature color.

Photographers love capturing these multicolor displays, and modern cameras can often pick up colors that are too faint for the human eye to see clearly, revealing even more complexity in the light show overhead.

8. Strong storms can push auroras to much lower latitudes than usual

Normally, auroras hug polar regions. But during severe storms, the auroral oval expands equatorward.

NOAA notes that in G5 (extreme) events, aurora can be seen as low as roughly 40° geomagnetic latitude (which can translate to surprisingly “far south” in many parts of the world). That means people in places like northern California, the central United States, southern Europe, or even parts of Japan might get a chance to see the lights.

The expansion happens because the geomagnetic storm distorts Earth’s magnetic field so much that the funnel effect reaches farther from the poles. Instead of particles being confined to a tight ring around the Arctic or Antarctic, they spread out over a much larger area.

This is why social media lights up (pun intended) during major storms, with aurora sightings reported from locations that almost never see them.

If you live at mid-latitudes and hear about a G4 or G5 storm forecast, it’s worth stepping outside on a clear, dark night and looking toward the pole (north in the Northern Hemisphere, south in the Southern Hemisphere). You might just catch a faint glow on the horizon or, if you’re lucky, a full-blown display overhead.

9. The ‘warning time’ can be short – even with modern monitoring

We can often spot eruptions on the Sun, but the exact impacts depend on how the CME’s magnetic field is oriented when it arrives. Fast CMEs can arrive in well under a couple of days; slower ones take longer. (That’s why forecasts tighten as the CME gets closer.) Scientists use satellites like SOHO and STEREO to watch the Sun for eruptions, and they can usually tell when a big CME is heading our way.

The tricky part is predicting the magnetic orientation of the CME. If the CME’s magnetic field is aligned opposite to Earth’s (a condition called “southward Bz”), it can couple very efficiently with our magnetosphere and cause a major storm.

If it’s aligned the same way (“northward Bz”), the impact is much weaker. We don’t know the orientation for certain until the CME reaches a monitoring satellite about a million miles from Earth, which gives us only about 15 to 60 minutes of advance warning before it hits.

That short window is why space weather forecasting is still a work in progress. Grid operators and satellite controllers use probabilistic forecasts and prepare for a range of scenarios, but they can’t know the exact severity until the storm is almost at our doorstep.

10. Satellites can get hit in multiple ways (and not all of them are obvious)

Major storms can cause spacecraft charging issues, tracking/orientation problems, and increased atmospheric drag in low Earth orbit, meaning satellites can lose altitude faster and need more corrections. Charging happens when energetic particles build up on a satellite’s surface or inside its electronics, creating voltage differences that can lead to short circuits or component failures.

Orientation problems arise because geomagnetic storms can interfere with a satellite’s onboard sensors, especially star trackers that use the positions of stars to determine which way the satellite is pointing. If those sensors get confused by energetic particles, the satellite might tumble or point its antennas or solar panels the wrong way.

That can disrupt communications or power generation.

Increased drag is a sneaky effect. During geomagnetic storms, Earth’s upper atmosphere heats up and expands, reaching higher altitudes where low-orbit satellites fly.

The thicker atmosphere creates more drag, slowing the satellites down and causing them to lose altitude faster than normal. Operators have to burn fuel more often to boost the satellites back up, which shortens their operational lifespans.

All these effects add up, making space weather a real operational headache for satellite operators worldwide.

11. GPS can still ‘work’, but accuracy and timing can degrade

Even when your phone still shows a location, geomagnetic storms can disrupt the ionosphere in ways that increase errors in GNSS/GPS positioning and timing, especially for precise applications (aviation, surveying, some financial timing systems). Your typical smartphone GPS might not notice much difference, showing you on the right street corner even during a storm.

But applications that need centimeter-level accuracy can see their errors balloon.

GPS signals travel through the ionosphere on their way from satellites to receivers on the ground. The ionosphere normally delays those signals in a predictable way, and GPS receivers correct for it.

During a geomagnetic storm, the ionosphere becomes turbulent and unpredictable, with rapid changes in density and structure. Those changes throw off the corrections, leading to positioning errors that can range from a few meters to tens of meters.

Timing is another critical issue. GPS satellites carry extremely accurate atomic clocks, and many systems (like cell towers, power grids, and financial networks) rely on GPS time signals to stay synchronized.

When ionospheric disturbances degrade the signal, timing errors can creep in, potentially causing problems for systems that depend on nanosecond-level precision. It’s a hidden vulnerability that most people never think about.

12. Radio communications can get patchy – especially at high latitudes

HF radio propagation can become unreliable during strong storms. In extreme events, certain regions can see major disruptions, which matters for aviation routes, maritime comms, and emergency systems that still rely on HF.

High-frequency (HF) radio signals bounce off the ionosphere to travel long distances, a technique that’s been used for decades by ships, planes flying over oceans, and remote communities.

When a geomagnetic storm churns up the ionosphere, those bounces become unpredictable. Signals might get absorbed instead of reflected, or scattered in random directions, making communication difficult or impossible.

Polar routes are especially vulnerable because that’s where the auroral zone is most active, and where the ionosphere is most disturbed during storms.

Pilots and air traffic controllers on transpolar flights sometimes have to switch to satellite communications as a backup, which can be more expensive and have limited bandwidth. Ham radio operators also notice the effects, with contests and long-distance contacts becoming much harder during active periods.

Even though we have satellite and internet-based comms now, HF radio remains a critical backup for many applications, and space weather is one of its biggest weaknesses.

13. Power grids are the ‘serious’ risk area but impacts vary by geography and preparedness

Extreme geomagnetic storms can induce currents in long conductors (like power lines), potentially creating voltage control issues and stressing transformers. Grid impacts depend heavily on local infrastructure, geology, latitude, and operational procedures.

The phenomenon is called geomagnetically induced currents, or GICs for short. When Earth’s magnetic field fluctuates rapidly during a storm, it creates electric fields in the ground, which drive currents through any long metal structures, including power transmission lines.

Transformers are particularly vulnerable. They’re designed to handle alternating current at specific frequencies (like 50 or 60 Hz), not the slow, quasi-DC currents that GICs produce.

When GICs flow through a transformer, they can cause it to saturate, overheat, and potentially fail. Replacing a large high-voltage transformer can take months and cost millions of dollars, and there aren’t many spares sitting around.

Geography matters a lot. Grids at higher latitudes (closer to the auroral zones) are more exposed.

Regions with resistive bedrock (like the Canadian Shield) allow GICs to flow more easily than areas with conductive rock. Modern grid operators monitor space weather forecasts and can take protective measures, like adjusting loads or temporarily taking vulnerable transformers offline, but not all grids worldwide have the same level of preparedness.

14. Solar radiation storms are different and matter most for astronauts and polar flights

Separate from geomagnetic storm ratings (G-scale), NOAA also tracks solar radiation storms (S-scale). Strong S-events can raise radiation risk for astronauts and can affect high-latitude aviation operations and communications.

Solar radiation storms happen when the Sun accelerates protons and other particles to very high energies, often during or after a solar flare. These particles can arrive at Earth in minutes to hours.

For astronauts on the International Space Station or future missions to the Moon or Mars, solar radiation storms are a serious health concern. High-energy protons can penetrate spacecraft shielding and deliver dangerous radiation doses.

During major events, astronauts might need to shelter in more heavily shielded areas of their spacecraft. NASA and other space agencies monitor the S-scale closely and have procedures to protect crew members.

High-altitude polar flights also get exposed to higher radiation levels during S-events because Earth’s magnetic field provides less shielding near the poles. Airlines sometimes reroute flights to lower latitudes during major storms to reduce crew and passenger radiation exposure.

It’s another example of how space weather, while invisible to most of us on the ground, has real operational consequences for people working in and above the atmosphere.

15. If you want to watch auroras, treat it like a ‘conditions’ checklist, not luck

To maximize your chances anywhere in the world when auroras expand: Check activity level (geomagnetic storm alerts and aurora forecasts), go dark (light pollution is the #1 aurora killer in populated areas), go north/south within your region if you can (toward higher latitudes helps), use a camera/phone night mode (your sensor often sees more than your eyes at first), be patient (aurora comes in bursts, not a steady glow). And ignore the myths: auroras don’t harm you at ground level – space weather is mostly a technology risk, not a “go inside immediately” situation.

Start by checking websites like NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center or apps that send aurora alerts. A Kp-index of 5 or higher means auroras are likely visible at mid-latitudes.

Clear skies are essential – clouds will block your view completely. Drive away from city lights; even a 20-minute drive can make a huge difference.

Once you’re in a dark spot, give your eyes at least 15 minutes to adjust.

Don’t expect a constant light show. Auroras often come in waves, with periods of activity followed by quieter stretches.

Your camera or phone can capture colors and details that your eyes might miss, especially faint reds and purples. And relax – standing outside watching an aurora won’t hurt you.

The particles causing the light are way up in the thermosphere, far above your head, and Earth’s atmosphere shields you completely from any radiation.