A massive crater suddenly opened near a Chilean mining town in 2022, and it has been causing fear and worry ever since. The sinkhole, which appeared close to homes and schools in Tierra Amarilla, was caused by underground copper mining that drained water from a crucial aquifer. Now, after years of investigations and legal battles, courts have ordered the mining company to fix the damage and close the mine permanently. This landmark case shows how mining can harm the environment and what happens when companies are held responsible for their actions.

How the Massive Crater Formed and Its Size

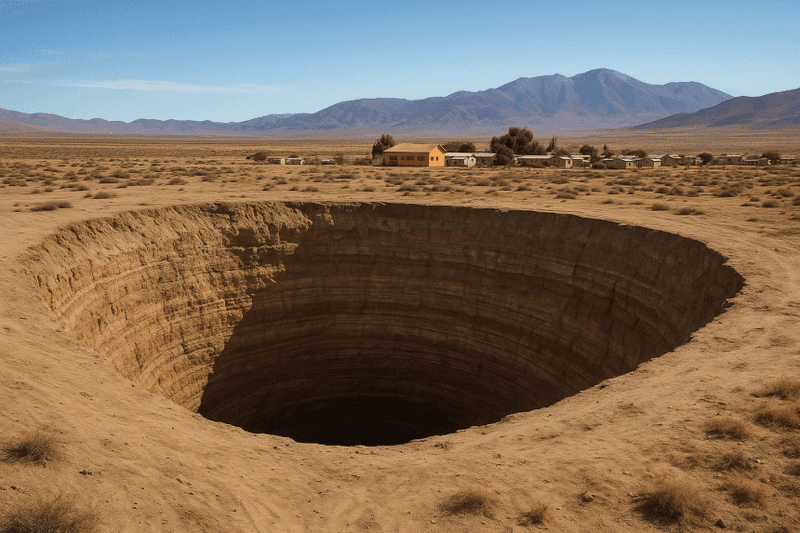

Back in August 2022, residents of Tierra Amarilla woke up to shocking news: a giant hole had appeared near their homes. The cylindrical crater measured about 32 meters across at the surface and plunged 64 meters deep into the earth. Located just 800 meters from residential areas, the sinkhole sits dangerously close to a health center and preschool.

Investigations revealed that the Alcaparrosa copper mine, operated underground by Lundin Mining’s subsidiary, had created an unnatural connection with the Copiapó River aquifer. Water drained into the mine, weakening the rock above and causing the ground to collapse suddenly. The region’s arid climate makes this water loss even more devastating.

Residents report clouds of dust rising from the crater during earthquakes, fueling fears that the hole might expand toward their homes and threaten their safety.

Permanent Mine Closure Ordered by Regulators

Chile’s environmental watchdog, known as the Superintendencia del Medio Ambiente or SMA, took decisive action in January 2025. Officials ordered the permanent shutdown of the Alcaparrosa Mine after determining it caused irreparable environmental damage to both the aquifer and surrounding rock formations. This wasn’t just a temporary suspension—the mine would never reopen.

Then came September 2025, when the First Environmental Court accepted a lawsuit filed by Chile’s State Defence Council. The court’s judgment went further than the initial closure order. It mandated that the mining company must refill the entire sinkhole, protect the damaged aquifer, and safeguard the region’s water supply.

The company must also present a comprehensive closure plan detailing exactly how they’ll repair the damage. This ruling represents one of Chile’s strongest environmental enforcement actions against a major mining operator.

Impact on Local Residents and Water Resources

For families living in Tierra Amarilla, the sinkhole has become a constant source of anxiety and sleepless nights. Rudy Alfaro, whose home sits just 800 meters from the crater’s edge, represents many residents who fear the hole could grow larger and swallow their neighborhood. Every tremor brings new worry that the ground beneath them might give way.

Beyond immediate safety concerns, the environmental damage runs deep. The court found that mining operations permanently altered groundwater flow patterns and changed the aquifer’s physical structure. Water quality deteriorated as the aquifer drained into the mine below.

This matters enormously in the Atacama region, one of Earth’s driest places. Water is already scarce, and every drop counts for drinking, farming, and daily life. The loss of aquifer integrity threatens the community’s long-term survival in this harsh desert environment.

Why This Case Matters for Mining Worldwide

What happened in Tierra Amarilla serves as a powerful warning about underground mining risks in water-scarce regions. When mining operations disturb aquifers, sudden geological collapses can happen without warning. The incident has become a landmark case in Chile’s environmental regulation of the mining industry.

Large mining companies now understand they can be held legally and financially accountable for hydrogeological instability they cause. Courts won’t accept excuses when operations damage crucial water resources. This sets an important precedent for mining operations worldwide, especially in arid zones where water systems are fragile.

The remediation challenge ahead is enormous. Engineers must refill a 64-meter-deep crater, stabilize weakened walls, address water ingress problems, and prevent further subsidence from ground motion. Restoring community trust will take even longer than the physical repairs. This process will likely span years and cost millions of dollars.