Viral headlines make bold promises, but the real story is richer, older, and far more interesting. You are about to see how genetics, archaeology, and oral tradition fit together like carefully knapped stone tools, each edge revealing something vital.

Recent studies spotlight deep time on the Northern Plains while community knowledge gives it heart and context. Keep reading to separate precision from spin and learn what the latest evidence actually shows.

1. Humans Were in North America Earlier Than Once Believed

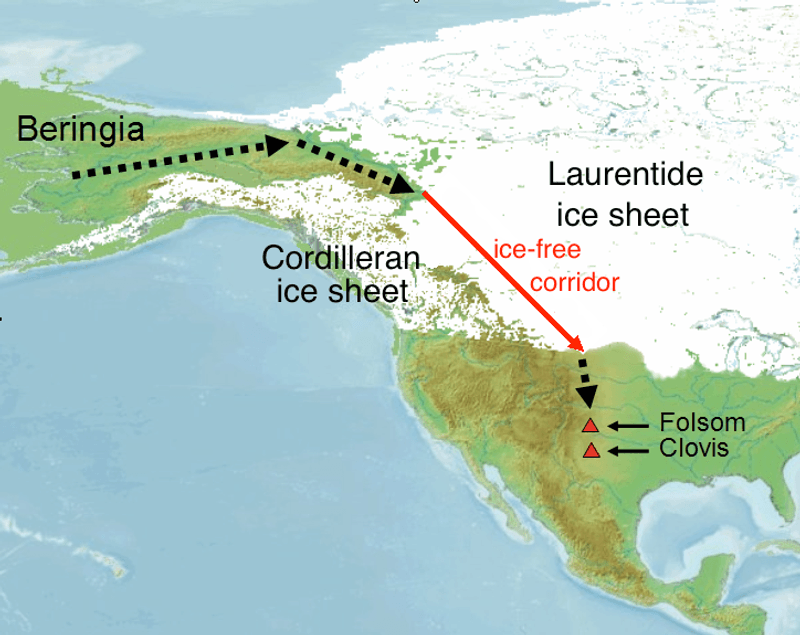

Early timelines just blinked and changed. Archaeology now places people in the Americas at least 15,000 to 16,000 years ago, supported by sites such as Monte Verde in Chile and the Buttermilk Creek Complex in Texas.

Some evidence suggests even older presence, though debates focus on dating precision and sediment disturbance.

What matters to you as a reader is that the old Clovis-first ceiling no longer holds. Human groups were exploring, adapting, and thriving across diverse habitats earlier than textbooks claimed a generation ago.

This shift reframes every regional story, including the Northern Plains.

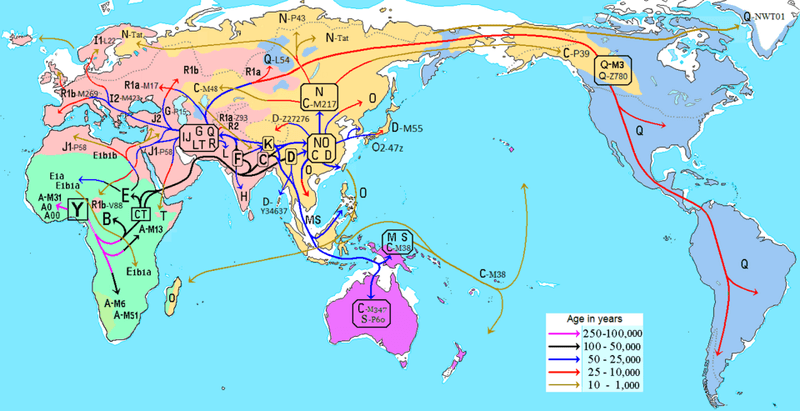

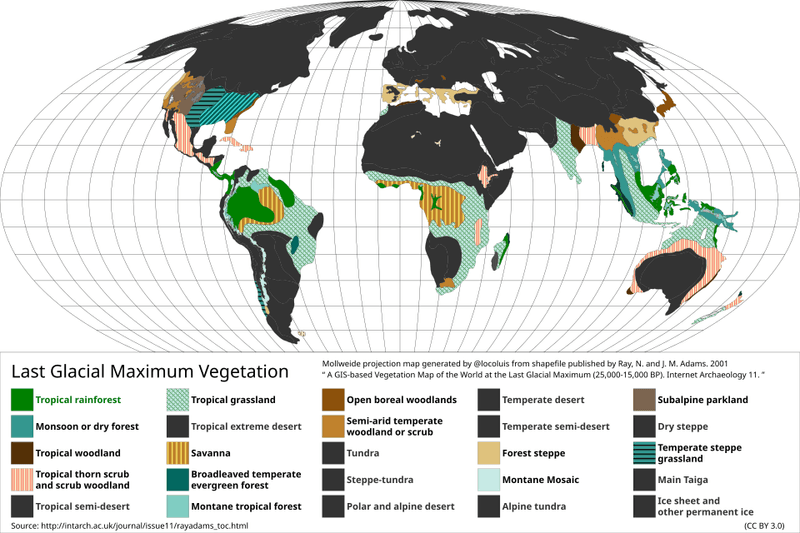

When you see numbers like 18,000 years, understand the broader context. Researchers discuss multiple entry routes, including an earlier Pacific coastal pathway, alongside interior corridors that opened later.

These models explain how people could reach far-flung regions quickly once ice barriers eased.

Evidence continues to be tested, refined, and reinterpreted. New techniques in radiocarbon calibration, sediment DNA, and optically stimulated luminescence keep sharpening the picture.

The trend line still points to earlier arrival.

For conversations about the Blackfeet Nation, this backdrop sets the stage. Ancient presence in the Americas is established, and the Northern Plains sit within that timeline.

The next question is how regional continuity is assessed.

2. The Northern Plains Have Deep Archaeological Roots

The Northern Plains hold time like a vault of wind and grass. Archaeological records document extensive human activity for more than 10,000 years, with campsites, bison jumps, tipi rings, and tool quarries tracing seasonal lifeways.

These sites show long familiarity with prairies, rivers, and changing climate.

One key data point is the Anzick site in present-day Montana. Dated to roughly 12,600 years ago, it includes the only known Clovis burial, with stone tools and ochre.

Genetic analysis linked the Anzick child to the broader ancestry of living Indigenous peoples.

Continuity does not mean stasis. Technologies, trade networks, and mobility patterns evolved as herds shifted and resources pulsed.

Yet the overall picture reveals deep regional roots that predate modern borders.

When you read about continuity on the Plains, think layered evidence. Hearth features, bison processing areas, and projectile point sequences create a timeline that is both local and continental.

Each site adds another stitch.

This regional depth is central to evaluating modern claims. Archaeology shows a long Indigenous presence across the Plains, including territories associated with Blackfeet ancestors.

It also guides respectful research questions today.

3. The Anzick Genome Shows Genetic Continuity

One child changed the conversation. The Anzick-1 genome, published in 2014, demonstrated a close genetic relationship between a Late Pleistocene individual in Montana and present-day Indigenous peoples across the Americas.

That result underscored population continuity over deep time.

To keep expectations clear, the data do not assign tribal identity. Genetics at this timescale reveals shared ancestry rather than specific political communities.

Still, the signal supports longstanding ties between ancient inhabitants and living nations.

You might wonder what this means for the Northern Plains. It strengthens evidence that early populations in the region contributed to the genetic heritage of many Indigenous groups.

The story is pan-continental, with local anchors.

Researchers emphasize careful interpretation. Clusters reflect historical population structure, drift, and movement, not fixed tribal boundaries.

Cultural affiliation requires multiple lines of evidence.

Even so, the Anzick genome acts as a cornerstone for discussions of continuity. It links the Plains to a broader dispersal narrative and validates deep ancestry that communities have voiced for generations.

Science here amplifies long-held knowledge.

4. Genetic Evidence Supports a Single Founding Population

A big-picture model ties many threads together. Most studies point to a primary founding population that spent time isolated in Beringia before dispersing into the Americas near the end of the Ice Age.

Subsequent migrations and local adaptations added texture.

For practical takeaways, that means shared deep ancestry among diverse Indigenous nations. Differences we see today emerged through language diversification, movement, and cultural innovation across thousands of years.

Genetics reveals kinship at continental scales.

You get a framework for evaluating claims about precise timelines. Founding pulses likely occurred between about 16,000 and 20,000 years ago, with coastal routes enabling earlier southward movement.

Interior corridors opened as ice retreated.

What this does not do is fix a modern nation’s borders in the Late Pleistocene. Tribal identities are historical and living, shaped by governance, alliance, and ceremony.

Biology informs ancestry, not political identity.

So when a headline names a single tribe at 18,000 years, read it as shorthand for ancient ancestry shared across related peoples. The nuance matters for accuracy and respect.

It also honors community narratives alongside data.

5. Tribal Identities Emerge Over Time

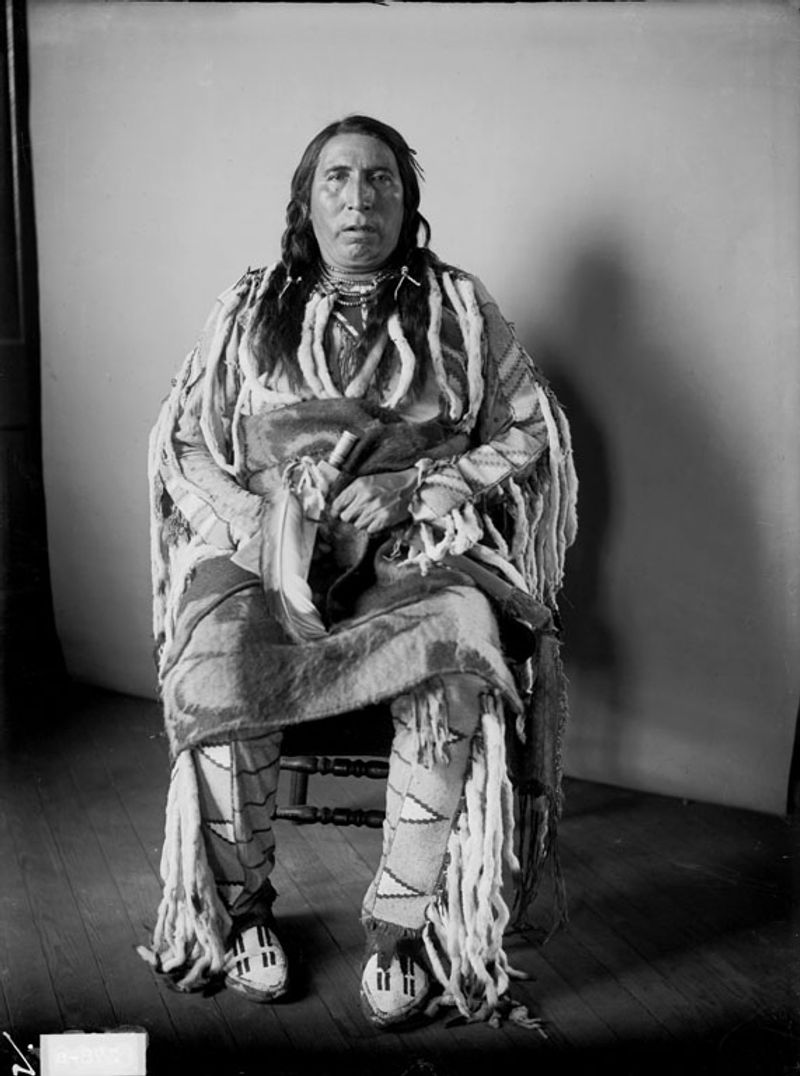

Culture does not sit still. Modern tribal nations developed through centuries of alliances, leadership, language shifts, and material changes, including the transformative arrival of the horse.

The Blackfeet Confederacy cohered politically in ways visible in historic records.

This point adds clarity without undercutting deep roots. Ancestors of today’s Blackfeet lived on the Plains long before those records, adapting to climate shifts and bison dynamics.

Identity layered gradually through kinship and governance.

You can hold two truths at once. There is ancient continuity in place and people, and there is also historical emergence of specific political communities.

Both are valid lenses.

Archaeology shows long Plains residence, while ethnography tracks later confederation structures. Oral traditions bind those threads to territory and responsibility.

The picture is complex and human.

Recognizing this evolution avoids false binaries. It respects living sovereignty while appreciating deep time.

That balance keeps the conversation honest.

6. The Blackfeet Language Belongs to the Algonquian Family

Words carry maps inside them. Blackfoot is an Algonquian language, linking it to a family spread across much of North America.

Linguists see patterns that hint at movements and contacts over centuries.

That does not erase place-based continuity. Language families can spread through trade, intermarriage, or shifting alliances, even as communities remain rooted.

Blackfoot retains features distinct to the Northern Plains.

You gain an extra layer of evidence to weigh with archaeology and genetics. Linguistic timelines are approximations, not GPS pins, yet they show relationships among peoples who exchanged ideas and stories.

The Plains sit well within those networks.

Scholars debate specific migration routes and timings. Some propose westward expansions that predate written records by long spans.

Others emphasize prolonged regional development.

Either way, language data suggests dynamism. It complements origin stories that affirm enduring ties to homeland.

The combined view supports depth and adaptability together.

7. Oral Traditions Preserve Deep Historical Memory

Stories remember what maps forget. Many Indigenous oral histories encode environmental changes and notable events across long spans, sometimes aligning with geological records.

Such knowledge travels through song, ceremony, and teaching.

For the Blackfeet, origin traditions tie people to the Northern Plains through kinship, landscape, and responsibility. These narratives guide stewardship and cultural practice.

They remain vital sources, not just footnotes.

You can see how science and story might meet. When archaeology finds ancient camps and genetics traces deep ancestry, oral accounts provide meaning and continuity.

Collaboration turns parallel lines into a braid.

Researchers increasingly design projects with community leadership. This approach respects intellectual sovereignty and refines research questions.

It also improves interpretation.

When headlines oversimplify, oral traditions help restore scale and purpose. They frame time not only as dates but as obligations to land and relatives.

That is evidence of a different kind.

8. Science Cannot Pinpoint One Modern Tribe 18,000 Years Ago

Precision has boundaries you should know. Ancient DNA reveals shared ancestry across broad regions but cannot cleanly tag a Late Pleistocene individual to a specific modern nation.

Tribal identity is historical, cultural, and political, not a genetic label.

That does not deflate continuity. It clarifies the scale at which claims can be responsibly made, protecting credibility.

Responsible language matters when rights and histories are at stake.

Think of the evidence as layered. Genetics shows relatedness, archaeology shows presence and practice, and oral tradition shows belonging and law.

Together they build a sturdy case without overreach.

Peer-reviewed work typically avoids naming present-day tribes for ancient remains unless multiple lines converge. Even then, conclusions remain cautious and respectful.

This is good science and good protocol.

So read viral posts with curiosity and care. Ask what level of identity the data truly address and what uncertainties remain.

The truth becomes stronger with that rigor.

9. Colonial Histories Underestimated Indigenous Antiquity

Old models missed the bigger horizon. For decades, Clovis-first defined a late entry narrative that compressed Indigenous timelines.

New evidence expanded the clock and diversified migration routes.

This revision had social weight. Underestimates of antiquity fed myths about recent arrival that undermined claims to land and continuity.

Correcting the record matters for policy and respect.

You can track how method updates changed minds. Better dating, stratigraphic controls, and cross-disciplinary work revealed richer early histories.

The result is a more accurate, more humane timeline.

Communities long carried stories of deeper presence. As data aligned, many saw affirmation rather than surprise.

Scholarship is finally catching up.

Today’s debates are narrower, focusing on routes and exact dates. The large point is settled: deep time is real.

That recognition reframes everything downstream.

10. Collaboration Between Scientists and Tribes Is Increasing

Partnership changes the questions first. Many projects now begin with community priorities, data governance plans, and cultural protocols.

The result is better science and better relationships.

Consultation around sensitive materials follows legal and ethical frameworks. NAGPRA guidance, tribal review boards, and memoranda of understanding structure consent and stewardship.

These steps protect community authority.

You gain more trustworthy outcomes this way. Interpretations align with lived knowledge, and findings return to communities in useful forms.

Trust builds over repeated collaborations.

The Anzick consultations helped set a template for broader practice. Teams learned to share results clearly and consider repatriation paths.

Respect is part of the method.

Collaboration also improves nuance in public communication. Headlines sharpen, caveats land, and context stays intact.

Everyone benefits from that clarity.

11. Documented Historical Presence for Centuries

Paper trails eventually caught up. European and American records from the 18th and 19th centuries repeatedly place the Blackfeet across the Northern Plains.

Ethnographers and traders documented territories, leadership, and lifeways.

These accounts confirm a strong presence before modern borders and states. They do not reach back to the Ice Age, but they anchor recent centuries with detail.

Together with archaeology, they outline long regional continuity.

You can see how different evidences interlock here. Written sources meet material culture, and both sit alongside oral tradition.

Triangulation strengthens conclusions.

Historical maps show extensive ranges across present-day Montana and Alberta. Seasonal movements followed bison, river crossings, and trade.

The pattern is robust in multiple archives.

For current readers, the key is accumulation. No single document proves deep time, but the pile is persuasive.

It points to endurance and adaptability.

12. Why Precision Strengthens the Claim

Good wording is not nitpicking. Precise claims keep the conversation credible and resilient against bad-faith pushback.

They also honor community guidance on how evidence should be framed.

The supported core is powerful on its own. Humans have been in the Americas since the late Ice Age, the Northern Plains show deep occupation, and modern Blackfeet communities share ancestry with ancient peoples.

Recent studies place lineage divergence near 18,000 years.

Here is the careful part you should carry forward. Science does not prove uninterrupted occupation by a named modern nation across that entire span, and it does not reduce belonging to molecules.

Cultural continuity lives in language, ceremony, and governance.

When you repeat the story, keep both hands on the truth. Celebrate deep time, cite the data, and include the caveat.

That balance respects sovereignty and strengthens advocacy.

In short, precision is an ally. It turns a viral claim into a durable understanding.

That is how knowledge lasts.