When you think about the American Revolution, names like George Washington and Paul Revere usually come to mind first. But many Black Americans also risked everything for independence, even though freedom was still denied to them.

Some fought in battle, others gathered intelligence, delivered messages, or challenged the idea of tyranny with their words and actions. For a long time, their contributions were pushed into the margins.

Some records were incomplete, some names were misspelled or reduced to a single line, and some stories were left out of paintings and popular retellings altogether. That is why so many of these lives still feel hidden, even though they helped shape the outcome of the war.

Here, you will meet eight Black patriots whose courage deserves a front-row place in the Revolution’s story. You will learn who they were, what they did, and why their impact still matters today.

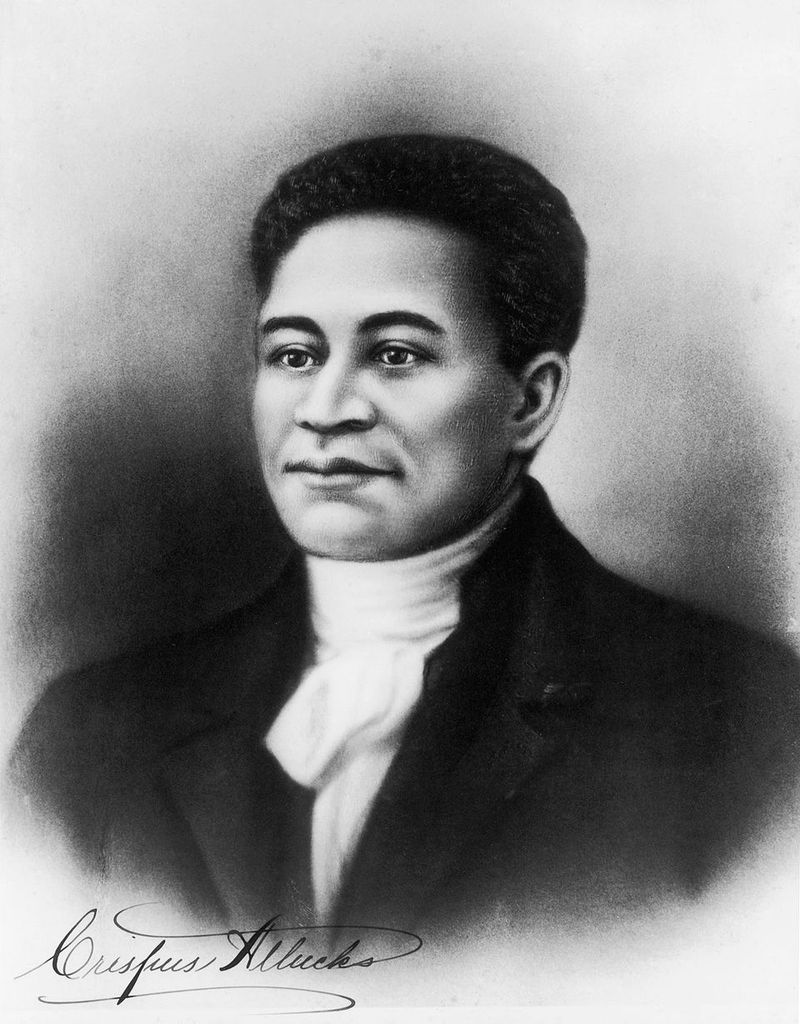

1. Crispus Attucks – The sailor whose death became a rallying cry

Blood on the snow has a way of changing everything. When British soldiers opened fire on a crowd in Boston on March 5, 1770, Crispus Attucks became the first to fall and suddenly, the Revolution had its first martyr.

Attucks wasn’t just any bystander. He was a sailor, a man of mixed African and Indigenous heritage who’d spent years navigating both the Atlantic and the dangerous waters of colonial society.

That night, he stood at the front of an angry crowd confronting armed Redcoats. His death, along with four others, ignited fury across the colonies.

Samuel Adams and other revolutionary leaders seized on the massacre as proof of British brutality. Attucks’s name appeared in newspapers, pamphlets, and fiery speeches.

He was buried with full honors alongside the other victims, a rare recognition for a man of color in that era. Yet after independence was won, his story faded.

It took decades before abolitionists reclaimed his legacy, reminding America that its first casualty of freedom was a Black man. Attucks proved that courage doesn’t wait for permission, and sometimes one death can awaken a nation.

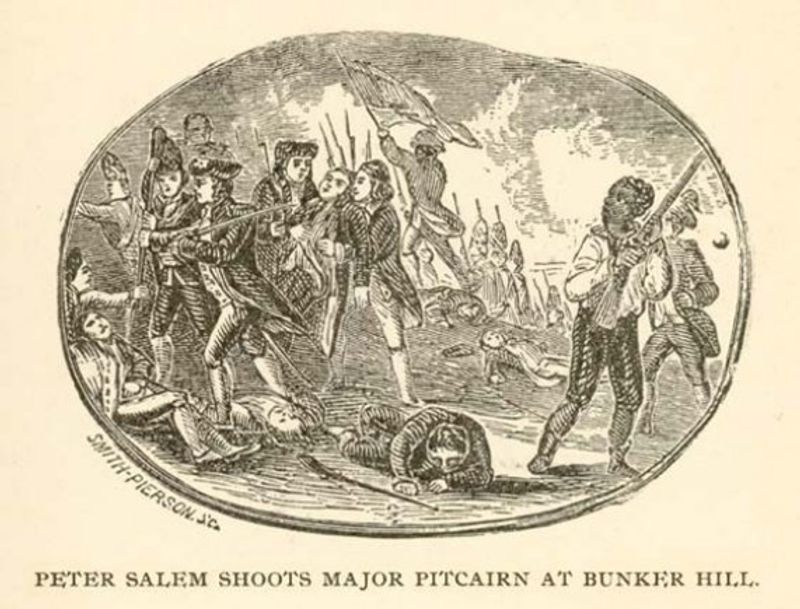

2. Peter Salem – The Bunker Hill figure America kept painting, then forgetting

Some people get painted into history, then brushed right back out. Peter Salem’s face appeared in multiple Revolutionary War artworks, most famously in depictions of Bunker Hill, yet his name vanished from the captions for generations.

Salem had been enslaved in Massachusetts before the war. When fighting broke out, he enlisted and found himself in the thick of the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775.

Accounts credit him with firing the shot that killed British Major John Pitcairn, a significant moment in a battle the colonists technically lost but morally won. Artists loved the drama of that moment.

Paintings showed Salem at the center of the action, musket raised, Pitcairn falling. But as decades passed, his identity got murky.

Some historians questioned whether he was really there; others merged his story with other Black soldiers. Eventually, researchers confirmed Salem’s service through military records and pension documents.

He fought through much of the war, surviving to see independence, though not equality. His story illustrates a frustrating pattern: Black patriots were celebrated when convenient, then conveniently forgotten when the narrative shifted.

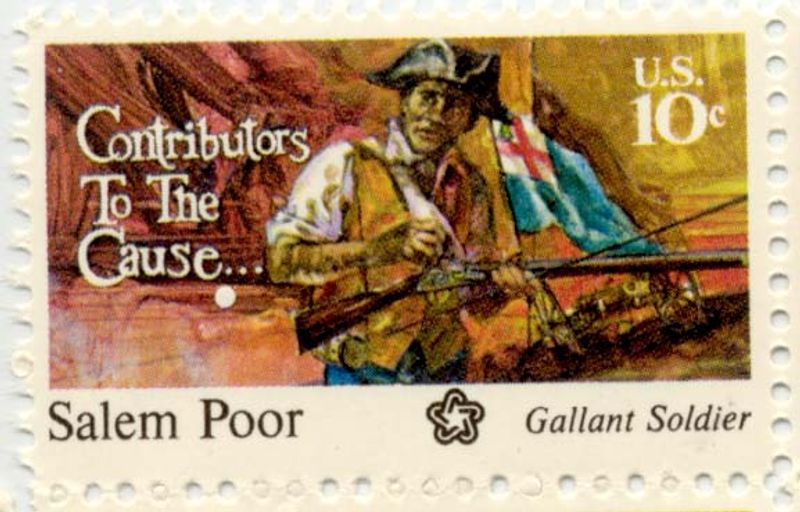

3. Salem Poor – The soldier formally praised for bravery at Bunker Hill

Getting your bosses to write you a glowing recommendation is tough. Getting fourteen Revolutionary War officers to sign a formal statement praising your bravery?

That’s nearly impossible, unless you’re Salem Poor. Poor bought his own freedom a year before the war started, paying his enslaver 27 pounds for the privilege of owning himself.

When the Revolution erupted, he immediately enlisted. At Bunker Hill, he fought with such distinction that his commanding officers felt compelled to document it.

The December 1775 petition to the Massachusetts General Court called Poor a “brave and gallant soldier” whose conduct was “distinguished.” This wasn’t casual praise, it was an official military commendation, extraordinarily rare for any soldier, let alone a Black man in an era when such recognition simply didn’t happen. Poor continued serving throughout the war, fighting in multiple campaigns.

Yet despite that remarkable petition, his story faded from popular memory. The document itself survived in archives, waiting for historians to rediscover it and recognize what it represented: undeniable proof that Black soldiers weren’t just present, they were exceptional.

Poor earned his place in history the hard way, and the paperwork proves it.

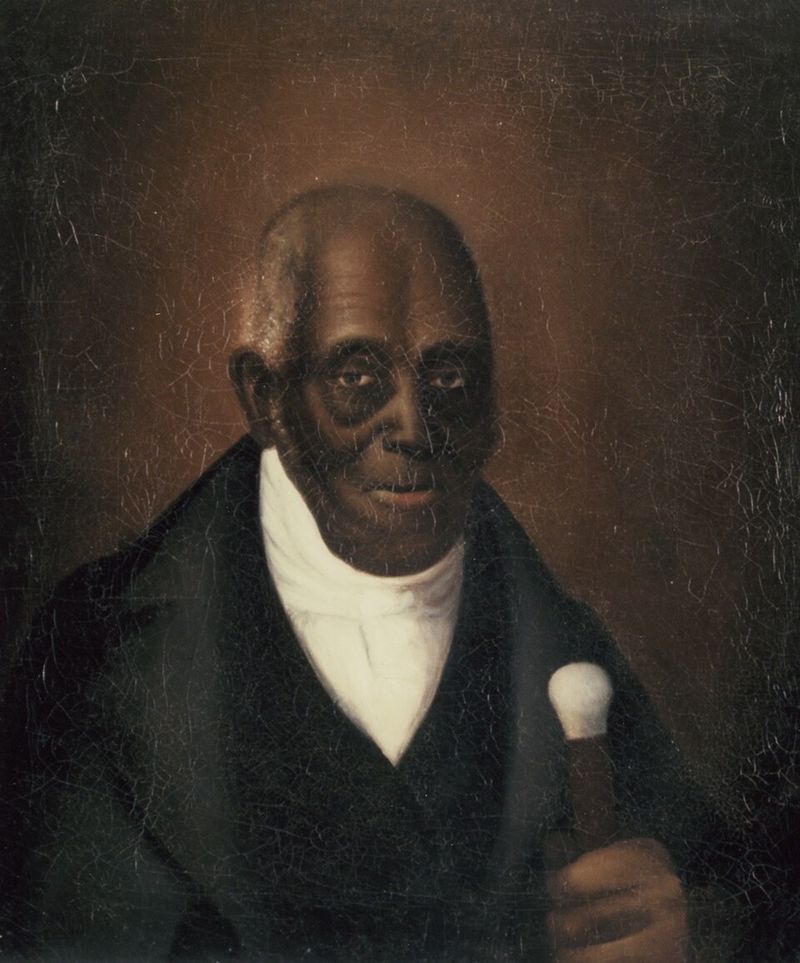

4. Agrippa Hull – The Continental Army orderly who served for years

Six years is a long time to spend at war. Agrippa Hull enlisted in 1777 as a free Black man from Massachusetts and served extensively throughout the Revolution, including time as an orderly to the Polish military engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko.

Hull’s role as an orderly meant more than just fetching and carrying. He assisted Kościuszko with engineering projects, correspondence, and daily operations, work that required intelligence, literacy, and trustworthiness.

The relationship between the two men apparently grew into genuine friendship, rare across both racial and class lines in that era. National Park Service documentation details Hull’s enlistment and wartime service, tracking him through multiple campaigns and years of conflict.

He witnessed the war’s evolution from desperate struggle to ultimate victory, serving longer than most soldiers could endure. After independence, Hull returned to Massachusetts and became a respected community member.

He married, raised a family, and lived to old age, a peaceful ending that many Revolutionary War veterans, Black or white, never achieved. Hull’s story matters because it’s so well-documented.

We know where he served, who he served with, and how he lived afterward. His life proves that Black soldiers weren’t just battlefield footnotes, they were essential, long-serving members of the Continental Army who earned their place in history through years of dedicated service.

5. James Armistead Lafayette – The spy who helped trap Cornwallis

Spying takes guts, especially when getting caught means hanging. James Armistead volunteered to infiltrate British lines, gathered intelligence that helped trap Cornwallis at Yorktown, and played a crucial role in ending the Revolutionary War.

Armistead was enslaved in Virginia when he received permission from his owner to join the American forces. He ended up working for the Marquis de Lafayette, who sent him into British camps posing as a runaway slave seeking freedom with the Redcoats.

The British believed his cover and put him to work, never suspecting he was feeding their plans directly to the Americans. The intelligence Armistead provided helped the American and French forces coordinate the siege of Yorktown in 1781.

His reports on British troop movements, supply situations, and Cornwallis’s intentions proved invaluable. When Cornwallis surrendered, effectively ending the war, Armistead’s espionage had helped make it possible.

Yet Armistead remained enslaved after the war. It took years of petitioning before Virginia finally granted him freedom in 1787.

He adopted “Lafayette” as his surname in honor of the general who’d recognized his service. The U.S.

Army now highlights Armistead’s wartime role, but his story was ignored for generations. He risked everything for American independence, and America’s thanks was delayed freedom and two centuries of historical neglect.

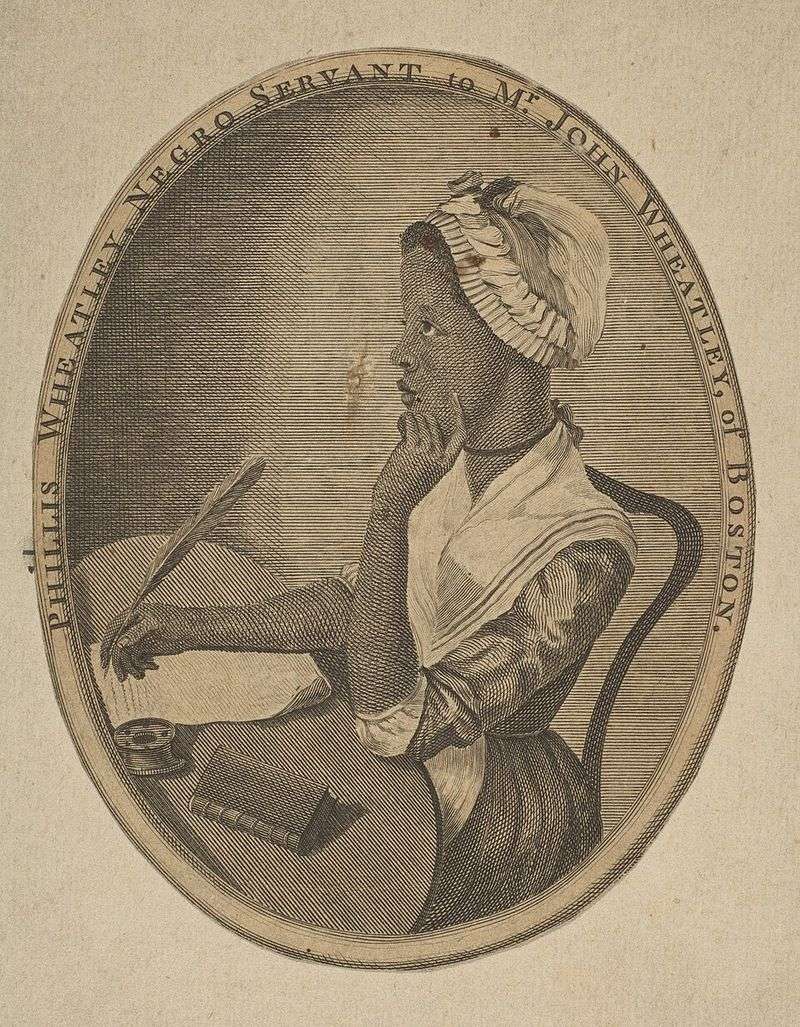

6. Phillis Wheatley Peters – The poet who chose the Patriot side

Poetry might seem like an unlikely weapon, but Phillis Wheatley Peters wielded it masterfully during the Revolution. She wrote to George Washington, published pro-Patriot verses, and proved that shaping America didn’t require a musket.

Wheatley was enslaved, brought from Africa as a child, and educated by the Boston family who owned her. She became the first published Black poet in America, achieving literary fame in both the colonies and England while still legally someone’s property.

When the Revolution erupted, Wheatley chose sides. In 1775, she wrote a poem honoring George Washington and sent it to him.

Washington was impressed enough to invite her to visit his headquarters, a remarkable gesture considering both her race and gender. Her poetry engaged Revolutionary ideas of liberty and freedom, though with an ironic edge, she wrote about freedom while enslaved.

Eventually freed, she married John Peters and took his surname, though her life remained difficult and she died young in poverty. Wheatley’s literary accomplishments during the Revolutionary era challenged every assumption about Black intellectual capability.

Her poetry was sophisticated, classical, and politically engaged. She proved that Black Americans could contribute to the Revolution through art, ideas, and words—not just military service.

Her pen was her musket, and she aimed it at tyranny with precision.

7. Prince Hall – The petitioner who confronted the Revolution’s biggest contradiction

Calling out hypocrisy takes courage, especially when the hypocrites are armed revolutionaries fighting for liberty. In 1777, Prince Hall petitioned the Massachusetts legislature against slavery, using the Revolution’s own ideals to demand freedom and rights.

Hall was a free Black man, a leather worker, and a community leader in Boston. While white colonists complained about British “tyranny” and “enslavement,” Hall pointed out the actual slavery happening right under their noses.

His petition didn’t ask for permission, it demanded justice. The petition explicitly invoked Revolutionary principles.

If all men are created equal, Hall argued, then slavery violated the very ideals America was fighting for. How could Massachusetts demand liberty from Britain while denying it to enslaved people?

Hall forced legislators to confront that contradiction. The petition didn’t immediately end slavery in Massachusetts, but it added pressure to the growing abolitionist movement.

Hall continued his activism for decades, founding the African Masonic Lodge and advocating for Black rights and education. What makes Hall’s 1777 petition so powerful is its timing.

The Revolution was still raging, victory was uncertain, and Hall demanded that America live up to its stated principles. He didn’t wait for independence to be won, he insisted that freedom meant nothing if it wasn’t universal.

His petition was as revolutionary as any battle, and arguably braver.

8. James Forten – The teenage privateer who became a powerhouse abolitionist

Teenage rebellion looks different when there’s a war on. At just fourteen or fifteen years old, James Forten went to sea aboard the privateer Royal Louis, fighting British ships and launching a lifetime of activism that would make him one of the 19th century’s most influential Black leaders.

Forten was born free in Philadelphia and could have stayed safely ashore, but he chose to serve. Privateers were privately owned ships authorized to attack enemy vessels,basically legal piracy in service of the Revolution.

It was dangerous work, especially for a teenager. His ship was eventually captured, and Forten became a British prisoner.

He was offered comfortable treatment in England if he’d switch sides, but refused. After his release, he returned to Philadelphia and began building the fortune and influence that would define his later life.

Forten became a successful sailmaker, amassing wealth he used to support abolitionist causes. He became a major figure in the anti-slavery movement, using his money, connections, and voice to fight for Black rights and the end of slavery.

His writing and activism influenced generations of abolitionists. Forten’s teenage service at sea was just the beginning.

He spent seventy years fighting for freedom, first with cannons, then with words, money, and moral authority. His life proves that patriotism isn’t a single act, it’s a lifelong commitment to making your country better.