Imagine water that’s been hidden underground for billions of years, untouched by rain, rivers, or oceans. In 2016, scientists made an incredible discovery deep inside a Canadian mine: the oldest known water on Earth. This ancient liquid has been sitting in darkness since before complex life even existed on our planet. One bold geologist even took a sip to prove just how remarkable this find truly was.

The Underground Discovery That Changed Everything

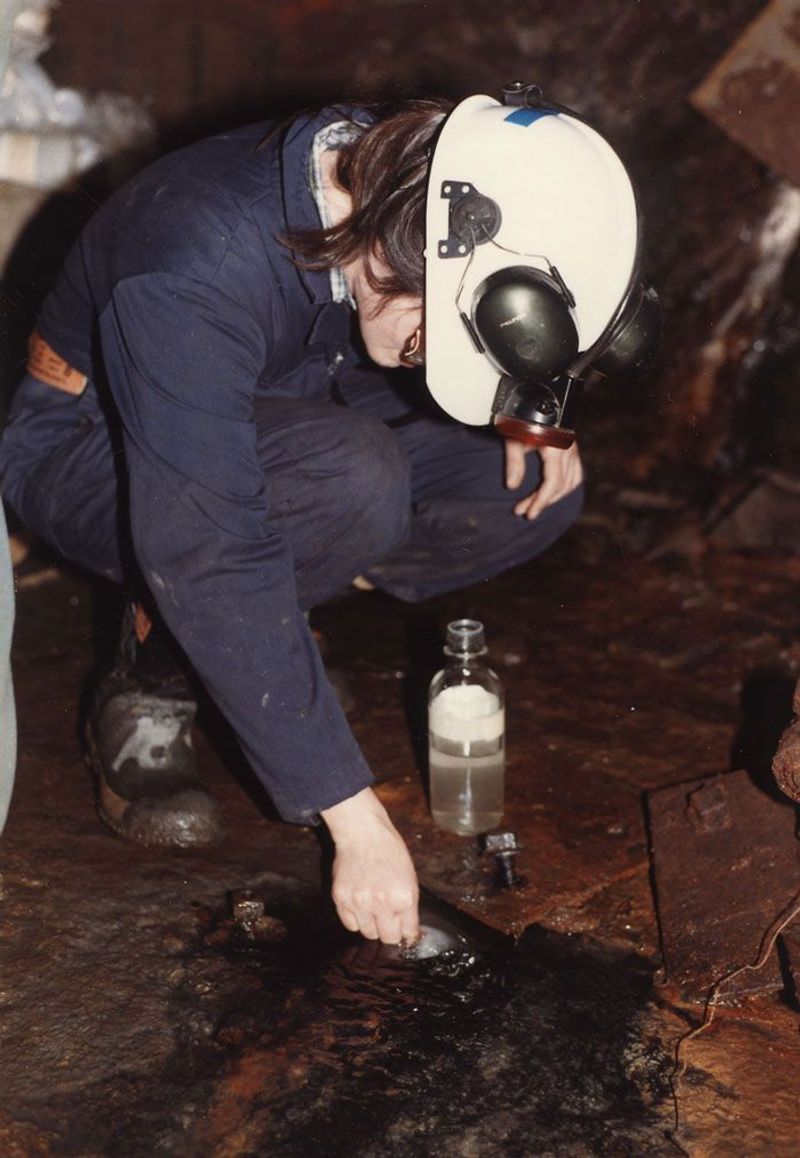

Professor Barbara Sherwood Lollar and her research team were exploring the Kidd Creek Mine in Ontario when they stumbled upon something extraordinary. At nearly 3 kilometers below the surface, they found water actively flowing from the rock at rates of several liters per minute. Unlike tiny trapped pockets, this was a substantial reservoir that had somehow remained isolated from the surface world.

Laboratory testing revealed the water’s mind-boggling age: somewhere between 1.5 and 2.6 billion years old. That means this water predates the dinosaurs by well over a billion years and existed when Earth’s atmosphere was still forming. The discovery challenged everything scientists thought they knew about underground water systems.

Finding such ancient, flowing water raised fascinating possibilities about what else might be lurking in Earth’s deep crust.

A Taste of the Ancient World

When Professor Sherwood Lollar decided to taste the billion-year-old water, she wasn’t being reckless—she was making a point. By taking that symbolic sip, she demonstrated confidence that this wasn’t some toxic alien substance but actual H2O that had simply been waiting in darkness for eons. Her verdict? The water was intensely salty and bitter, far saltier than ocean water.

The extreme saltiness came from billions of years of mineral accumulation. As the water sat isolated in the rock, it slowly dissolved surrounding minerals, becoming a concentrated brine. The bitter taste likely came from dissolved metals and other compounds leached from the ancient stone.

While memorable, the tasting wasn’t really about flavor. It symbolized that despite its extreme age, this water still connected us to Earth’s distant past in a tangible, almost drinkable way.

A Window Into Earth’s Hidden Biosphere

Chemical analysis of the ancient water revealed something even more exciting than its age: traces of sulfur compounds that indicated microbial life had once thrived there. Microorganisms had somehow survived in complete darkness, cut off from sunlight and the surface ecosystem for unimaginable stretches of time. This challenged assumptions about where life could exist and for how long.

The discovery opened up entirely new questions about Earth’s deep biosphere. Could communities of microbes still be living down there today? How do they get energy without sunlight? What does this mean for the search for life on Mars or the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn?

Scientists now view Earth’s crust as a potential haven for life in extreme environments, offering clues about survival in the harshest conditions imaginable.

Unanswered Questions and Future Exploration

Despite the groundbreaking discovery, many mysteries remain unsolved. The age estimates rely on complex isotopic modeling, which comes with significant uncertainty ranges. Scientists still debate exactly how the water remained isolated for so long and what chemical processes kept it stable through billions of years of geological activity.

Researchers continue investigating how these deep aquifers connect to crustal geology and whether similar reservoirs exist elsewhere on Earth. They’re also refining their dating techniques to narrow down the age range more precisely. Each new sample from deep mines adds pieces to the puzzle.

The symbolic act of drinking the water, while attention-grabbing, doesn’t guarantee complete safety—trace contaminants could still exist. Moving forward, scientists plan to explore more deep water systems worldwide, hoping to unlock secrets about our planet’s interior and the limits of life itself.